Corcu Loígde

The Corcu Loígde (Corcu Lóegde, Corco Luigde, Corca Laoighdhe, Laidhe), meaning Gens of the Calf Goddess,[4][5] also called the Síl Lugdach meic Itha, were a kingdom centred in West County Cork who descended from the proto-historical rulers of Munster, the Dáirine, of whom they were the central royal sept. They took their name from Lugaid Loígde "Lugaid of the Calf Goddess", a King of Tara and High King of Ireland, son of the great Dáire Doimthech (a quo Dáirine). A descendant of Lugaid Loígde, and their most famous ancestor, is the legendary Lugaid Mac Con, who is listed in the Old Irish Baile Chuinn Chétchathaig. Closest kin to the Corcu Loígde were the Dál Fiatach princes of the Ulaid.

| Corcu Loígde | |

|---|---|

| Parent house | Dáirine/Érainn |

| Country | Ireland |

| Founded | 1st century AD |

| Founder | Lugaid Loígde |

| Current head | none, although modern descendants of the last O'Driscoll princes are known[1] |

| Final ruler | Fineen O'Driscoll[2] Uí Meic Thaile [3] |

| Titles |

|

| Dissolution | 17th century AD |

| Cadet branches | O'Leary of Iveleary O'Flynn Arda O'Connor O'Hennessey |

Overview

The Corcu Loígde were the rulers of Munster, and likely of territories beyond the province, until the early 7th century AD, when their ancient alliance with the Kingdom of Osraige fell apart as the Eóganachta rose to power. Many peoples formerly subject to the Corcu Loígde then transferred their allegiance to the Eóganachta, most notably the influential Múscraige, an Érainn people related only very distantly to the Corcu Loígde. The Múscraige became the chief facilitators for the Eóganachta in their rise to power. Uí Néill interference has also been suggested as a major factor,[6] motivated by a desire to see no more Kings of Tara from the Corcu Loígde.

However, from Aimend, daughter of Óengus Bolg, the Corcu Loígde are related to the inner circle of the Eóganachta through a legendary marriage, as she became the wife of Conall Corc.[7][8][9] They enjoyed a privileged status in the history of the new dynasty. As former rulers of the province the Corcu Loígde were not a tributary kingdom, a status also enjoyed by the Osraige.

In the 12th century they had their kingdom erected into the Diocese of Ross, and their O'Driscoll lords played a significant maritime role in the region.[10] Coffey, O'Leary, Hennessy, and Flynn (O'Flynn Arda) were other families of importance,[11][12] as well as the literary family of Dinneen. O'Hea,[13] Cronin, Dunlea, and other families also may belong to the Corcu Loígde.

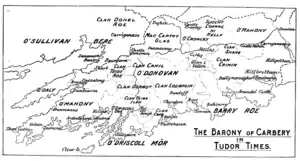

A substantial part of the profitable maritime lands once dominated solely by the Corcu Loídge were incorporated into the medieval Barony of Carbery, in which the O'Driscolls would retain some status as one of the three princely families underneath the MacCarthy Reaghs. Some of the western portion of their territory became the Barony of Bantry.

See also School of Ross.

Legendary pedigree

Several of the following were misplaced chronologically by later medieval synchronists.

- Bolg (Sithbolg)

- Dáire Doimthech a quo Dáirine

- Lugaid Loígde a quo Corcu Loígde

- ... (possibly missing generations)

- Mac Con

- Mac Nia (alternatively Mac Con's father or double)

- Lugaid

- Óengus Bolg = Coel, a quo Úi Builc

- Nath Í (Na Tri)

- Etarscél a quo O'Driscoll

- Maine a quo Úa Maine

- Liadán = Lugna

- Aimend = Conall Corc

- Nath Í (Na Tri)

- Óengus Bolg = Coel, a quo Úi Builc

- Duach

- Gérán

- Conall Clóen (line of Coffey)

- Threna

- Óengus a quo Úi Óengusa (Hennessy)

- Mac Eircc (line of O'Leary)

- Gérán

- Eochaid (or Fiachra)

- Badomna (line of O'Flynn Arda)

- Lugaid

- Fothad Cairpthech and Fothad Airgthech

- Mac Nia (alternatively Mac Con's father or double)

- Mac Con

- Rechtaid Rígderg

- ... (possibly missing generations)

- Eochaid Étgudach

- Lugaid Loígde a quo Corcu Loígde

- Dáire Doimthech a quo Dáirine

Another Irish monarch belonging to the Corcu Loígde was Eochaid Apthach,[14] but if in any way historical he has not only been misplaced chronologically but cannot be even placed in the above pedigree due to the extensive corruption of the supposed generations preceding "Bolg" (Sithbolg). It was early noted by John O'Donovan and has been noted repeatedly by all his successors that the Corcu Loígde genealogies are among the most confused in the entire Irish corpus, so the above scheme should be understood with that in mind.

One important generation not reproduced here is that of Deda (a quo Clanna Dedad), the most recent common ancestor of the Dál Fiatach and Dál Riata of Ulster and Scotland in several official pedigrees. However, variants of his name can be found in the early generations of several Corcu Loígde pedigrees: Deaghmanrach,[15] Deadhmannra and Deagha Dearg.[16]

Legend and history

A peculiar fact about the Corcu Loígde is their almost total lack of political activity following the mid Early Middle Ages. Having formerly held sway over a vast territory, they appear to have almost completely disintegrated over the course of the 7th century, never making any serious attempts to recover what was at that time the largest kingdom in Ireland. Thus over the next centuries their former grandeur became more and more the stuff of legend, around which the younger kingdoms built their own origin legends. The most well known tale in this cycle is the Cath Maige Mucrama.

Satellite kingdoms

Former satellite kingdoms of the Corcu Loígde, and who may once have been closely related to them, were probably the early medieval sister kingdoms of Uí Fidgenti and Uí Liatháin. Evidence for this is that not only do they appear to have been artificially attached to the stem of the Eóganachta, whose own pedigree is very unreliable before Conall Corc, but that important early septs like the Uí Duach Argetrois of Osraige cannot be definitively attached to the lines of either the Uí Liatháin-Fidgenti or the Corcu Loígde. In addition there were an early line of O'Learys attached to the Uí Fidgenti.

Later centuries

By the late 16th century the two most prosperous families remaining were the Ó hEidirsceoil princes, with several castles in and around Baltimore, including Dunasead Castle, and the O'Learys, who had built several castles south of Macroom.

The Ó hEidirsceoil's and Baltimore

The history of the Ó hEidirsceoil clan and the seaside village of Baltimore are inextricably linked. The first historical mention of the Ó hEidirsceoil (anglicised O'Driscoll) clan occurs in the Annals of Inisfallen where the death in 1103 of Conchobar Ua hEtersceóil king of Corcu Loígde was recorded. The surname O'Driscoll is an anglicised form of the Gaelic Ó hEidirsceóil which has the meaning of "diplomat" or "interpreter." (eidir 'between' + scéal 'story', 'news').

The originator of the name is thought to have lived in the 9th century. Prominent in the village today is the restored castle of Dunasead (castle of jewels) which was an Ó hEidirsceoil stronghold built around 1600 as a fortified house probably by Sir Fineen Ó hEidirsceoil, who was a knight of Queen Elizabeth I. As the power of the Corcu Loígde alias Dáirine as Kings of Munster, Tara, and a large part of Ireland faded in the Dark Ages, their empire broken up, their center of political power shifted south into the wild country of West Cork, or Ross Carbery as it is known in local history, and this is where the O'Driscoll clan has been prominent throughout history.

Baltimore is a strategic harbour town on Roaringwater Bay located west of Kinsale and east of Mizen Head. The west side of Baltimore harbour is bounded by Sherkin Island which protects it from the prevailing westerly winds and seas. The north side is bounded by Ringarogy island and Spanish Island (also known as Green's Island), which lie in the mouth of the Ilen river. The harbour has two main entrances. The entrance on the south side, called the Harboursmouth, gives direct access to the sea, and is marked by a stone pillar painted white (known locally as "The beacon") on the mainland side, and by a lighthouse at Barracks point on Sherkin Island. On the north side, there is a channel between Sherkin Island and Spanish Island. During the medieval period which was the height of the Ó hEidirsceoil's influence, they controlled the fortresses of Dún na Long (The fort of ships) on Sherkin Island, Dún na Séad (The fort of jewels) at Baltimore, and Dún an Óir (The fort of gold) on Cape Clear, as well as another near Lough Ine, which is a salt water lake on the nearby coast to the east of Baltimore. The Ó hEidirsceoil heritage is territorially associated with these lands around Baltimore, and an oral legend has it that if any seafarer were to land on the Islands of Sherkin or Clear or the mainland of West Carbery, that an Ó hEidirsceoil would require payment of a dockage fee. The Ó hEidirsceoil's were historically a seafaring clan who had up to 100 sailing vessels in their fleet which were used in both fishing and policing the local waters. The Ó hEidirsceoil's in this era were known to trade extensively with France, Portugal and Spain. Merchant ships whether they were foreign or from neighbouring towns such as Waterford when sailed into Ó hEidirsceoil waters were sometimes considered fair game.

Sir Fineen is remembered locally as somewhat of a rogue since as a political expedience he opened the local lands to English "planters" and in doing so saved his homelands from falling to local invasion by the local O'Mahony, O'Leary and MacCarthy clans, with the help of the English whose fleet he harboured. Sir Fineen himself was driven in his dotage to live on a small island in Lough Ine as a recluse and oral history claims that he grew rabbit's floppy ears. He is said to have died in England or Spain on a mission to Queen Elizabeth I whose death preceded his own. His heirs may have survived in Baltimore and abroad but were never again political chiefs in the historical era.

Several years after Sir Fineen's demise, the village of Baltimore suffered a catastrophic defeat as recorded in the Annals of Kinsale, when it was sacked in 1631 by Algerian mercenaries led by a Dungarvan man John Hackett who was later hanged for this crime of revenge. Legend has it that Hackett's boat was seized by the Algerians and that he refused to guide them into Kinsale but instead led the Barbary coast pirates to Baltimore claiming its riches possibly because of the historical dispute between Waterford and the Ó hEidirsceoils. Ironically, nearly all of the 107 captives that were taken from Baltimore by the Turks were for the most part the English "planters," who were made into galley slaves or harem girls and only two of whom were ever returned to Ireland.

The Ó hEidirsceoil's appear to have survived the Sack of Baltimore quite well either in the offshore islands or by clinging to the highlands of "The Hill" overlooking Baltimore's cove where the pirates landed, or retreating to the surrounding hollows or to the upstream town of Skibbereen. To the current time the Ó hEidirsceoil's claim ownership of "The Hill" in Baltimore as well as many lots and farms in the Islands as well as on the nearby River Ilen and to many other properties in West Cork.

The O'Learys

- Auliffe O'Leary – joined the side of Hugh O'Neill, 2nd Earl of Tyrone in the Nine Years' War

- Art Ó Laoghaire – immortalised by his widow Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill in the Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire

- Peadar Ua Laoghaire – celebrated Irish language writer and descendant of the lords of Carrignacurra

French wine

Corcu Loígde trade with France dates from the Middle Ages. The Ó hEidirsceoils are known from an early time to have had a trading fleet active along the French Atlantic Coast in the Bay of Biscay, as far south as Gascony, importing wine back to their region and into Munster.[17]

Hennessy Cognac

After serving as a mercenary for Louis XV of France, the Corcu Loígde nobleman Richard Hennessy would establish his famous Hennessy Cognac on land given him by the king in compensation. Several of his descendants have gone on to distinguish themselves in French politics, notably Jean Hennessy.[18]

See also

Citations

- Ó Murchadha, p. 185

- The O'Driscolls of West Cork

- The O'Coffeys, rulers of what was known as the Middle Cantred, were displaced by the MacCarthys Reagh after the Norman invasion and the surviving remainder of Corca Laidhe was ruled by the O'Driscolls, who had already been its co-rulers from an early period.

- Charles-Edwards 2000, p. 186

- O'Rahilly 1946, p. 3

- Charles-Edwards

- Byrne 2001, pp. 166,193

- Charles-Edwards 2000, p. 611

- Hull 1947

- Byrne 2001, p. 180

- O'Donovan 1849

- O'Hart 1892

- The O'Hea are also given a Dál gCais pedigree by O'Hart, pp. 218–9. Whether this is accurate, erroneous, or there are two distinct septs is difficult to determine.

- Irish Monarchs of the Race of Ithe

- O'Donovan 1849, p. 25

- O'Donovan 1849, p. 57 (Genealogy of O'Driscoll)

- recently mentioned by Charles Doherty in 'Érainn', in Seán Duffy (ed.), Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2005. p. 156

- François Dubasque, Les frères Hennessy, deux riches héritiers en politiques, Arkheia, Montauban, 2008.

General references

- Edel Bhreathnach (ed.), The Kingship and Landscape of Tara. Four Courts Press for The Discovery Programme. 2005.

- Francis John Byrne, Irish Kings and High-Kings. Four Courts Press. 2nd revised edition, 2001.

- Thomas Charles-Edwards, Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge. 2000.

- Myles Dillon, The Cycles of the Kings. Oxford. 1946. Four Courts Press edition, 1995.

- Vernan Hull, "Conall Corc and the Corco Luigde", in Proceedings of the Modern Languages Association of America 62:4 (1947): 887–909. JSTOR 459137.

- Geoffrey Keating, with David Comyn and Patrick S. Dinneen (trans.), The History of Ireland by Geoffrey Keating. 4 Vols. London: David Nutt for the Irish Texts Society. 1902–14.

- Paul MacCotter, Medieval Ireland: Territorial, Political and Economic Divisions. Four Courts Press. 2008.

- Edward MacLysaght, Irish Families: Their Names, Arms and Origins. Irish Academic Press. 4th edition, 1998.

- Eoin MacNeill, "Early Irish Population Groups: their nomenclature, classification and chronology", in Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (C) 29. 1911. pp. 59–114

- Gearóid Mac Niocaill, Ireland before the Vikings. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. 1972.

- Kuno Meyer (ed.), "Conall Corc and the Corco Luigde. From Laud 610, fol. 98 a", in O. J. Bergin et al. (ed), Anecdota from Irish manuscripts iii (Halle a.S & Dublin 1910): 57–63.

- Kuno Meyer (ed.), "The Laud Genealogies and Tribal Histories", in Zeitschrift für Celtische Philologie 8. Halle/Saale, Max Niemeyer. 1912. pp. 291–338.

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin, "Corcu Loígde: Land and Families", in Cork: History and Society. Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County, edited by Patrick O'Flanagan and Cornelius G. Buttimer. Dublin: Geography Publications. 1993.

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin (ed.), Genealogies from Rawlinson B 502. University College, Cork: Corpus of Electronic Texts. 1997.

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin, Ireland before the Normans. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. 1972. 2nd edition (Four Courts Press), 2009.

- Donnchadh Ó Corráin, "Prehistoric and Early Christian Ireland", in Foster, Roy (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland. Oxford University Press. 2001. pp. 1–52.

- John O'Donovan (ed. and tr.), Annála Ríoghachta Éireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters, from the Earliest Period to the Year 1616. 7 vols. Royal Irish Academy. Dublin. 1848–51. 2nd edition, 1856.

- John O'Donovan (ed. and tr.), "The Genealogy of Corca Laidhe", in Miscellany of the Celtic Society. Dublin. 1849. alternative scan

- John O'Hart, Irish Pedigrees. Dublin. 5th edition, 1892.

- Diarmuid Ó Murchadha, Family Names of County Cork. Cork: The Collins Press. 2nd edition, 1996.

- T. F. O'Rahilly, Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. 1946.

- Pokorny, Julius. "Beiträge zur ältesten Geschichte Irlands (3. Érainn, Dári(n)ne und die Iverni und Darini des Ptolomäus)", in Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie 12 (1918): 323–57.