Corn dolly

Corn dollies or corn mothers are a form of straw work made as part of harvest customs of Europe before mechanisation.

Before Christianisation, in traditional pagan European culture it was believed that the spirit of the corn (in American English, "corn" would be "grain") lived amongst the crop, and that the harvest made it effectively homeless. James Frazer devotes chapters in The Golden Bough to "Corn-Mother and Corn-Maiden in Northern Europe" (chs. 45–48) and adduces European folkloric examples collected in great abundance by the folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt. Among the customs attached to the last sheaf of the harvest were hollow shapes fashioned from the last sheaf of wheat or other cereal crops. The corn spirit would then spend the winter in this home until the "corn dolly" was ploughed into the first furrow of the new season.

Background

James George Frazer discusses the Corn-mother and the Corn-maiden in Northern Europe, and the harvest rituals that were being practised at the beginning of the 20th century:

In the neighbourhood of Danzig the person who cuts the last ears of corn makes them into a doll, which is called the Corn-mother or the Old Woman and is brought home on the last waggon. In some parts of Holstein the last sheaf is dressed in women's clothes and called the Corn-mother. It is carried home on the last waggon, and then thoroughly drenched with water. The drenching with water is doubtless a rain-charm. In the district of Bruck in Styria the last sheaf, called the Corn-mother, is made up into the shape of a woman by the oldest married woman in the village, of an age from 50 to 55 years. The finest ears are plucked out of it and made into a wreath, which, twined with flowers, is carried on her head by the prettiest girl of the village to the farmer or squire, while the Corn-mother is laid down in the barn to keep off the mice. In other villages of the same district the Corn-mother, at the close of harvest, is carried by two lads at the top of a pole. They march behind the girl who wears the wreath to the squire's house, and while he receives the wreath and hangs it up in the hall, the Corn-mother is placed on the top of a pile of wood, where she is the centre of the harvest supper and dance.[1]

Many more customs are instanced by Frazer. For example, the term "Old Woman" (Latin vetula) was in use for such "corn dolls" among the Germanic pagans of Flanders in the 7th century, where Saint Eligius discouraged them from their old practices: "[Do not] make vetulas, (little figures of the Old Woman), little deer or iotticos or set tables [for the house-elf, compare Puck] at night or exchange New Year gifts or supply superfluous drinks [a Yule custom]."[2] Frazer writes: "In East Prussia, at the rye or wheat harvest, the reapers call out to the woman who binds the last sheaf, “You are getting the Old Grandmother....In Scotland, when the last corn was cut after Hallowmas, the female figure made out of it was sometimes called the Carlin or Carline, that is, the Old Woman."[3]

The mechanisation of harvesting cereal crops probably brought an end to traditional straw dolly and figure making at the beginning of the 20th century.[4] In the UK corn dolly making was revived in the 1950s and 1960s. Farm workers created new creations including replicas of farm implements and models such as windmills and large figures.[5] New shapes and designs with different techniques were being created. In the 1960/70s several books were published on the subject. (see Lettice Sandford) The simple origins of the craft had been lost and new folk lore stories were added to the original ideas.[6]

The Pitt Rivers Museum[7] in Oxford and the Museum of English Rural Life in Reading both have collections of corn dollies from around the world.[8]

Materials used

- Great Britain: mainly wheat, oats, rye and barley

- Ireland: rush

- Southern France: palm leaves

With the advent of the combine harvester, the old-fashioned, long-stemmed and hollow-stemmed wheat varieties were replaced with knee-high, pithy varieties. However, a number of English and Scottish farmers are still growing the traditional varieties of wheat, such as Maris Wigeon, Squarehead Master, Elite Le Peuple.[9] mainly because they are in great demand in thatching, a craft which is enjoying a renaissance, with customers facing long waiting lists for having their roofs thatched or repaired.

Types

Corn Dollies and other similar harvest straw work can be divided into these groups:

Traditional corn dollies named after counties or place names of England, Scotland and Wales

Barton Turf dolly, Norfolk

Barton Turf dolly, Norfolk Cambridgeshire Handbell

Cambridgeshire Handbell

Hereford Lantern

Hereford Lantern

Suffolk Horseshoe

Suffolk Horseshoe Yorkshire Spiral or Drop Dolly

Yorkshire Spiral or Drop Dolly

- Other corn dollies include Anglesey Rattle, Cambridgeshire Umbrella, Durham Chandelier, Claidheach (Scotland) Herefordshire Fan, Kincardine Maiden (Scotland), Leominster Maer (Herefordshire), Norfolk Lantern, Northamptonshire Horns, Okehampton Mare, Oxford Crown, Suffolk Bell, Suffolk Horseshoe and Whip, Teme Valley Crown (Shropshire), Welsh Border Fan, Welsh Long Fan, Worcester Crown.

- There are also corn dolly designs from other countries, for example the Kusa Dasi from Turkey, named after the town of Kuşadası.

Countryman's favours and other harvest designs

A countryman's favour was usually a plait of three straws and tied into a loose knot to represent a heart. It is reputed to have been made by a young man with straws picked up after the harvest and given to his loved one. If she was wearing it next to her heart when he saw her again then he would know that his love was reciprocated. Three straws can be plaited using the hair plait or a cat's foot plait. Favours can be made with two, three, four or more straws.

Countryman's Favour in barley

Countryman's Favour in barley Glory Braid

Glory Braid Cornucopia (Horn of plenty)

Cornucopia (Horn of plenty) Corn Maiden

Corn Maiden Harvest Cross

Harvest Cross Harvest Wreath

Harvest Wreath Corn maiden

Corn maiden Countryman's Favours

Countryman's Favours

Other examples include:

- Bride of the Corn ("Aruseh" in North Africa)

- Devonshire Cross, a harvest cross from Topsham, Devon

- Dedham Cross

- St Brigid's Cross; the National Museum of Ireland has many examples of harvest crosses.

Fringes

- Larnaca Fringe

- Montenegrin Fringe

- Lancashire Fringe

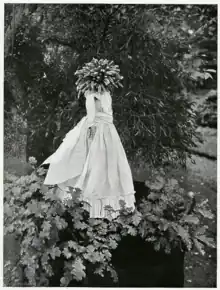

Large straw figures

These are representations of deities, animals or spirits, made from an entire sheaf. They are known by a variety of names, depending on location and also the time of harvesting:

- The Goddess Ceres

- Maiden or Bride (harvest before All Saints):

- Kirn Dolly (Roxburghshire)

- Kirn Baby (Lothians)

- Kern Baby (Northumberland)

- The Neck (Cornwall and Devon)

- Hare (Galloway)

- Lame Goat, Scottish Gaelic: gobhar bacach (Harris, Skye, Glenelg)

- Straw dog - strae bikko (Shetland, Orkney)

- Cailleach Gaelic: Old Woman or The Hag (harvest after All Saints)

- Caseg Fedi or harvest mare in Wales.

- 'Y Wrach' or 'The Hag' in Caernarvonshire, Wales

- Whittlesey Straw Bear, the centre of a ceremony in Whittlesey, Cambridgeshire, every January. Its origins are obscure.

Tied straw work

Here the straw is not plaited, but tied with yarn, wool, raffia or similar. This type of straw work is particularly popular in Scandinavia and German-speaking countries. Examples of these are the Oro (Swedish Straw Crown); the Tomte or Nisse; and smaller versions of the Yule Goat.

Tied straw work

Tied straw work Swedish Dwarves

Swedish Dwarves Reindeer garland

Reindeer garland Large tied star

Large tied star

Ridge finials

- These are straw sculptures which are placed on the ridge of the thatched roof. They are sometimes purely for decoration, but can be the signature of a particular thatcher. Animal shapes (birds, foxes etc.) are the most common. In days gone by, hay-ricks would also be thatched, and topped with a straw decoration.

See also

- Æcerbot

- Corn husk doll

- Crying the Neck

- Didukh, sheaf of grain, also believed to contain spirits, and also stored inside the house over winter, in East Slavic cultures.

- Food grain

- Harvest festival

- John Barleycorn

- Kadomatsu

- Mistletoe

- Poppet

- Straw plaiting

- The Corn Dollies (band)

- The Green Man

- Wicker man

References

- The Golden Bough, chapter 45

- Saint Ouen of Rouen; trans. Jo Ann McNamara. The Life of Saint Eligius (Vita Sancti Eligii). Archived from the original on 2013-05-08.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Frazer, ch. 45.

- Adkins, Roy and Lesley. "Corn Dollies". Adkins History. Adkins History. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Mizen, Brian. "Fred Mizen". Fred Mizen. Brian Mizen Thatching. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- Carpenter, Daniel. "Corn Dolly Making". Corn Dolly Making. Heritage Crafts Association. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Harvest Trophies". England: The Other Within. Pitt Rivers Museum. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Coker, Alec (corn dollies)". Coker, Alec (corn dollies). Museum of English Rural Life. Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- "Guild of Straw Craftsmen - Frequently asked questions". Strawcraftsmen.co.uk. 2008-08-16. Retrieved 2014-06-25.

Further reading

External links

- Sir James George Frazer, The Golden Bough, chapter 45, and § 2. The Rice-mother in the East Indies

- The Guild of Straw Craftsmen UK association for all aspects of straw craft

- "Putting out the hare, putting on the harvest knots" Irish harvest customs

- Neil Thwaites Yorkshire corn dolly crafter