Corundum

Corundum is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) typically containing traces of iron, titanium, vanadium, and chromium.[3][4] It is a rock-forming mineral. It is a naturally transparent material, but can have different colors depending on the presence of transition metal impurities in its crystalline structure.[7] Corundum has two primary gem varieties: ruby and sapphire. Rubies are red due to the presence of chromium, and sapphires exhibit a range of colors depending on what transition metal is present.[7] A rare type of sapphire, padparadscha sapphire, is pink-orange.

| Corundum | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide mineral – Hematite group |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Aluminium oxide, Al2O3 |

| IMA symbol | Crn[1] |

| Strunz classification | 4.CB.05 |

| Dana classification | 4.3.1.1 |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class | Hexagonal scalenohedral (3m) H-M symbol: (3 2/m) |

| Space group | R3c (No. 167) |

| Unit cell | a = 4.75 Å, c = 12.982 Å; Z = 6 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Colorless, gray, golden-brown, brown; purple, pink to red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet; may be color zoned, asteriated mainly grey and brown |

| Crystal habit | Steep bipyramidal, tabular, prismatic, rhombohedral crystals, massive or granular |

| Twinning | Polysynthetic twinning common |

| Cleavage | None – parting in 3 directions |

| Fracture | Conchoidal to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 9 (defining mineral)[2] |

| Luster | Adamantine to vitreous |

| Streak | Colorless |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent, translucent to opaque |

| Specific gravity | 3.95–4.10 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (−) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.767–1.772 nε = 1.759–1.763 |

| Pleochroism | None |

| Melting point | 2,044 °C (3,711 °F) |

| Fusibility | Infusible |

| Solubility | Insoluble |

| Alters to | May alter to mica on surfaces causing a decrease in hardness |

| Other characteristics | May fluoresce or phosphoresce under UV light |

| References | [3][4][5][6] |

| Major varieties | |

| Sapphire | Any color except red |

| Ruby | Red |

| Emery | Black granular corundum intimately mixed with magnetite, hematite, or hercynite |

The name "corundum" is derived from the Tamil-Dravidian word kurundam (ruby-sapphire) (appearing in Sanskrit as kuruvinda).[8][9]

Because of corundum's hardness (pure corundum is defined to have 9.0 on the Mohs scale), it can scratch almost all other minerals. It is commonly used as an abrasive on sandpaper and on large tools used in machining metals, plastics, and wood. Emery, a variety of corundum with no value as a gemstone, is commonly used as an abrasive. It is a black granular form of corundum, in which the mineral is intimately mixed with magnetite, hematite, or hercynite.[6]

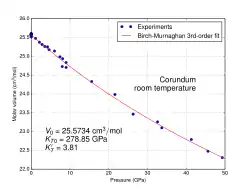

In addition to its hardness, corundum has a density of 4.02 g/cm3 (251 lb/cu ft), which is unusually high for a transparent mineral composed of the low-atomic mass elements aluminium and oxygen.[10]

Geology and occurrence

Corundum occurs as a mineral in mica schist, gneiss, and some marbles in metamorphic terranes. It also occurs in low-silica igneous syenite and nepheline syenite intrusives. Other occurrences are as masses adjacent to ultramafic intrusives, associated with lamprophyre dikes and as large crystals in pegmatites.[6] It commonly occurs as a detrital mineral in stream and beach sands because of its hardness and resistance to weathering.[6] The largest documented single crystal of corundum measured about 65 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm (26 in × 16 in × 16 in), and weighed 152 kg (335 lb).[11] The record has since been surpassed by certain synthetic boules.[12]

Corundum for abrasives is mined in Zimbabwe, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Russia, Sri Lanka, and India. Historically it was mined from deposits associated with dunites in North Carolina, US, and from a nepheline syenite in Craigmont, Ontario.[6] Emery-grade corundum is found on the Greek island of Naxos and near Peekskill, New York, US. Abrasive corundum is synthetically manufactured from bauxite.[6]

Four corundum axes dating to 2500 BC from the Liangzhu culture and Sanxingcun culture (the latter of which is located in Jintan District) have been discovered in China.[13][14]

Synthetic corundum

- In 1837, Marc Antoine Gaudin made the first synthetic rubies by reacting alumina at a high temperature with a small amount of chromium as a colourant.[15]

- In 1847, J. J. Ebelmen made white synthetic sapphires by reacting alumina in boric acid.

- In 1877, Frenic and Freil made crystal corundum from which small stones could be cut. Frimy and Auguste Verneuil manufactured artificial ruby by fusing BaF2 and Al2O3 with a little chromium at temperatures above 2,000 °C (3,630 °F).

- In 1903, Verneuil announced that he could produce synthetic rubies on a commercial scale using this flame fusion process.[16]

The Verneuil process allows the production of flawless single-crystal sapphire and ruby gems of much larger size than normally found in nature. It is also possible to grow gem-quality synthetic corundum by flux-growth and hydrothermal synthesis. Because of the simplicity of the methods involved in corundum synthesis, large quantities of these crystals have become available on the market at a fraction of the cost of natural stones.[17]

Apart from ornamental uses, synthetic corundum is also used to produce mechanical parts (tubes, rods, bearings, and other machined parts), scratch-resistant optics, scratch-resistant watch crystals, instrument windows for satellites and spacecraft (because of its transparency in the ultraviolet to infrared range), and laser components. For example, the KAGRA gravitational wave detector's main mirrors are 23 kg (50 lb) sapphires,[18] and Advanced LIGO considered 40 kg (88 lb) sapphire mirrors.[19] Corundum has also found use in the development of ceramic armour thanks to its high hardiness.[20]

Structure and physical properties

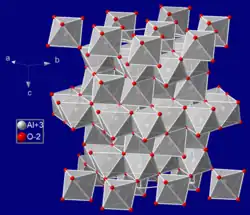

Corundum crystallizes with trigonal symmetry in the space group R3c and has the lattice parameters a = 4.75 Å and c = 12.982 Å at standard conditions. The unit cell contains six formula units.[21][4]

The toughness of corundum is sensitive to surface roughness[22][23] and crystallographic orientation.[24] It may be 6–7 MPa·m1/2 for synthetic crystals,[24] and around 4 MPa·m1/2 for natural.[25]

In the lattice of corundum, the oxygen atoms form a slightly distorted hexagonal close packing, in which two-thirds of the octahedral sites between the oxygen ions are occupied by aluminium ions.[26] The absence of aluminium ions from one of the three sites breaks the symmetry of the hexagonal close packing, reducing the space group symmetry to R3c and the crystal class to trigonal.[27] The structure of corundum is sometimes described as a pseudohexagonal structure.[28]

Generalization

Because of its prevalence, corundum has also become the name of a major structure type (corundum type) found in various binary and ternary compounds.[29]

See also

- Aluminium oxynitride

- Gemstone

- Spinel – natural and synthetic mineral often mistaken for corundum

References

- Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- "Mohs' scale of hardness". Collector's corner. Mineralogical Society of America. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C., eds. (1997). "Corundum". Handbook of Mineralogy (PDF). Vol. III Halides, Hydroxides, Oxides. Chantilly, VA, US: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 0962209724. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-09-05.

- "Corundum". Mindat.org.

- "Corundum". Webmineral.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2006.

- Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). Wiley. pp. 300–302. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- Giuliani, Gaston; Ohnenstetter, Daniel; Fallick, Anthony E.; Groat, Lee; Fagan; Andrew J. (2014). "The Geology and Genesis of Gem Corundum Deposits". Gem Corundum. Research Gate: Mineralogical Association of Canada. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0-921294-54-2.

- Harper, Douglas. "corundum". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Jeršek, Miha; Jovanovski, Gligor; Boev, Blažo; Makreski, Petre (2021). "Intriguing minerals: corundum in the world of rubies and sapphires with special attention to Macedonian rubies". ChemTexts. 7 (3): 19. doi:10.1007/s40828-021-00143-0. ISSN 2199-3793. S2CID 233435945.

- "The Mineral Corundum". galleries.com.

- Rickwood, P. C. (1981). "The largest crystals" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 66: 885–907. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-06-20.

- "Rubicon Technology grows 200 kg "super boule"". LED Inside. 21 April 2009.

- "Chinese made first use of diamond". BBC News. BBC. May 2005.

- Alexandra, Goho. "In the Buff: Stone Age tools may have derived luster from diamond". Science News. Science News.

- Duroc-Danner, J. M. (2011). "Untreated yellowish orange sapphire exhibiting its natural colour" (PDF). Journal of Gemmology. 32 (5): 175–178. doi:10.15506/jog.2011.32.5.174. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2013.

- Bahadur (1943). "A Handbook of Precious Stones". Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- Walsh, Andrew (February 2010). "The commodification of fetishes: Telling the difference between natural and synthetic sapphires". American Ethnologist. 37 (1): 98–114. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1425.2010.01244.x.

- Hirose, Eiichi; et al. (2014). "Sapphire mirror for the KAGRA gravitational wave detector" (PDF). Physical Review D. 89 (6): 062003. Bibcode:2014PhRvD..89f2003H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.062003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-24.

- Billingsley, GariLynn (2004). "Advanced Ligo Core Optics Components – Downselect". LIGO Laboratory. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Defense World.Net, Russia’s Armored Steel-Comparable Ceramic Plate Clears Tests, 5th September 2020, Retrieved 29th December 2020

- Newnham, R. E.; de Haan, Y. M. (August 1962). "Refinement of the α Al2O3, Ti2O3, V2O3 and Cr2O3 structures*". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 117 (2–3): 235–237. Bibcode:1962ZK....117..235N. doi:10.1524/zkri.1962.117.2-3.235.

- Farzin-Nia, Farrokh; Sterrett, Terry; Sirney, Ron (1990). "Effect of machining on fracture toughness of corundum". Journal of Materials Science. 25 (5): 2527–2531. Bibcode:1990JMatS..25.2527F. doi:10.1007/bf00638054. S2CID 137548763.

- Becker, Paul F. (1976). "Fracture-Strength Anisotropy of Sapphire". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 59 (1–2): 59–61. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1976.tb09390.x.

- Wiederhorn, S. M. (1969). "Fracture of Sapphire". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 52 (9): 485–491. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1969.tb09199.x.

- "Corundum, Aluminum Oxide, Alumina, 99.9%, Al2O3". www.matweb.com.

- Nesse, William D. (2000). Introduction to mineralogy. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 363–364. ISBN 9780195106916.

- Borchardt-Ott, Walter; Kaiser, E. T. (1995). Crystallography (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 230. ISBN 3540594787.

- Gea, Laurence A.; Boatner, L. A.; Rankin, Janet; Budai, J. D. (1995). "The Formation Al 2 O 3 /V 2 O 3 Multilayer Structures by High-Dose Ion Implantation". MRS Proceedings. 382: 107. doi:10.1557/PROC-382-107.

- Muller, Olaf; Roy, Rustum (1974). The major ternary structural families. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-06430-3. OCLC 1056558.