Coucher de soleil no. 1

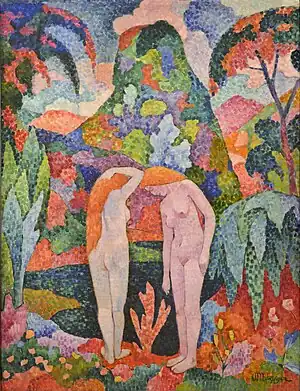

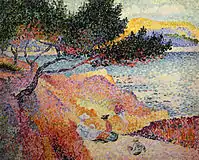

Coucher de soleil no. 1 (also called Landscape, Paysage, Landschap, or Sunset No. 1) is an oil painting created circa 1906 by the French artist and theorist Jean Metzinger (1883–1956). Coucher de soleil no. 1 is a work executed in a mosaic-like Divisionist style with a Fauve palette. The reverberating image of the Sun in Metzinger's painting is an homage to the decomposition of spectral light at the core of Neo-Impressionist color theory.

| Coucher de soleil no. 1 | |

|---|---|

| English: Sunset No. 1 | |

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_72.5_x_100_cm%252C_Rijksmuseum_Kr%C3%B6ller-M%C3%BCller%252C_Otterlo%252C_Netherlands.jpg.webp) | |

| Artist | Jean Metzinger |

| Year | c. 1906 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 72.5 cm × 100 cm (22.5 in × 39.25 in) |

| Location | Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo |

| Website | Museum page |

Coucher de soleil was exhibited in Paris during the spring of 1907 at the Salon des Indépendants (n. 3457), along with Bacchante and four other works by Metzinger.[1]

The painting had been in the collection of Helene Kröller-Müller since 1921 or prior,[2] now in the collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands.[3]

Description

Coucher de soleil no. 1 is an oil painting on canvas in a horizontal format with dimensions 72.5 cm × 100 cm (28.5 in × 39.4 in), signed J.Metzinger (lower right), and titled on the verso "Coucher de soleil no. 1". Also on the verso is another painting by Metzinger representing a river scene with ships.

The work represents two nude women relaxing in a lush Mediterranean landscape with semi-tropical vegetation, hills, trees, a body of water and a radiating setting Sun beyond.[4] The plants to the lower left resemble the agave, a species found in the south of France, Spain and Greece. "Agave" is also the name of three characters in Greek mythology:

- Agave: one of the Nereids.[5][6][7][8]

- Agave: one of the Danaïdes, daughter of Danaus and Europa. She married Lycus, son of Aegyptus and Argyphia.[9]

- Agave: an Amazon.[10]

The two nudes appear to play a secondary role in the overall composition due to their small size. But their prominent location in the foreground and the provocative nature of public nudity propels them to a position that cannot be ignored.[4]

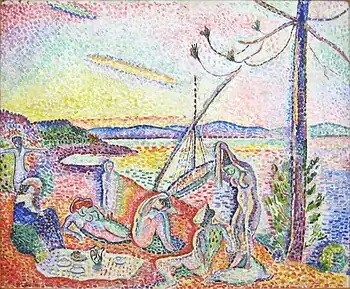

In this luscious setting—as in Luxe, Calme et Volupté by Henri Matisse—Metzinger makes use all the colors in the spectrum of visible light. Unlike Matisse's work, Metzinger's brushstrokes are large, forming a mosaic-like lattice of squares or cubes of similar size and shape throughout, juxtaposed in a wide variety of angles relative to one another, creating an overall rhythm that would otherwise not be present.[4]

%252C_oil_on_canvas%252C_73_x_54_cm_DSC05359...jpg.webp)

Evidence suggests that this work was completed prior to Metzinger's paintings entitled La danse (Bacchante) or Two Nudes in an Exotic Landscape: (1) there exists an oil on canvas study of the latter dated circa 1905–1906, located at the University of Iowa with the title Two Nudes in a garden, 91.4 x 63.8 cm with a similar radiating sun above the bathers. (2) The brushstrokes are smaller in size consistent with Metzinger's style of late 1905. (3) In 1906 and 1907 Metzinger's brushstrokes became larger and more organized, structured within a highly geometrized framework already proto-Cubist in appearance. (4) As its name implies, Coucher de soleil no. 1 might have been the first in a series of sunsets. Though no other works by Metzinger are known by the titles Coucher de soleil no. 2 or No. 3, the artist did produce other works with sunsets during the same period: Landscape with Fountain, for example, an oil on canvas measuring 53.3 x 73.6 cm; Paysage pointilliste, 1906–07, an oil on canvas measuring 54.5 x 73 cm; Matin au Parc Montsouris, ca. 1906, oil on canvas, 49.9 x 67.7 cm; or even La tour de Batz au coucher de soleil, 54 x 73 cm, an oil on canvas ca. 1905.[4]

These clues would seem to suggest Coucher de soleil no. 1 was painted during the later months of 1905, or early 1906, just before Metzinger and Robert Delaunay began painting portraits of one another,[11] rather than circa 1908 as indicated by the Kröller-Müller Museum.[3][4]

Neo-Impressionism, Divisionism

The Fauves (many of whom would become Cubists), were heavily influenced by Neo-Impressionism, calling upon rational and scientific thought and creating highly abstract visions with the goal of producing the effects of real color-light. Mechanical brushwork suppressed the personality of the artist in an act of conspicuous defiance against the Impressionists.[4] The Symbolists too would strip away the casual and accidental features of reality, revealing the true 'essence of form.' Whether such a revelation could be backed up by a scientific theory or not, there were still examples that could be codified. The problem was that pigments reflect light, they are not a light source themselves. Colors in the spectra of light did not respond in the same way as color pigments painted on canvas. For example, red and blue light rays result in white light, but the same colors in pigments make violet.[4][12][13]

Metzinger's response in Coucher de soleil no. 1, in addition to illustrating actual radiation emanating in concentric circles from the sun, was to separate colors in such a way as to avoid mixtures, leading to inert tones. Contrary to the Impressionists related hues, often placed on top of one another while still wet—leading to a result the Divisionists found dull—contrasting hues placed side by side for the effect or creating optical vibrations were essential to Divisionists.[4][12][13]

The basic elements of art—the line, particle of color—like words could be treated autonomously, each possessing an abstract value independent of one another, if so chose the artist. The line, independent of its topographical role, possesses an calculable abstract value, in addition to the particles of color and the relation of both to the observer's emotion. The underlying theory behind Neo-Impressionsim, something Divisionists like the Metzinger would push to the extreme, would have a lasting effect on the works produced in the coming years by Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay and Gino Severini.[4][12]

The impulse toward abstraction was a primary quality of the time, even prior to Metzinger's Sunset No. 1. "Neo-Impressionism" wrote Paul Adam, "wants to reproduce the pure phenomenon, the subjective appearance of things. It is a school of abstraction."[4][12]

By "abstract," writes Robert Herbert, "writers and painters of the period did not mean "devoid of reference to the real world", as we now use the term. They meant to draw away from nature, in the sense of disdaining imitation in order to concentrate upon the distillation of essential shapes and movements. These distilled forms were superior to nature because they partook of idea, and represented the dominance of the artist over the mere stuff of nature. In embryo, the Symbolists and Neo-Impressionists did establish the philosophical defense of pure abstraction, but nature still formed part of the basic dialogue."[4][12]

By 1905 Metzinger began to favor the abstract qualities of larger brushstrokes and luminous colors. Following the lead of Georges Seurat, Henri-Edmond Cross and Paul Cézanne, Metzinger began incorporating a new geometry into his works that signified a further departure still from naturalism.[4][12][13]

Robert Herbert writes of Metzinger's Coucher de soleil and its importance during the Neo-Impressionist period and thereafter:

- "At the Indépendants in 1905, his paintings were already regarded as in the Neo-Impressionist tradition by contemporary critics, and he apparently continued to paint in large mosaic strokes until some time in 1908. The height of his Neo-Impressionist work was in 1906 and 1907, when he and Delaunay did portraits of each other [...] in prominent rectangles of pigment. (In the sky of [Coucher de soleil, 1906-1907, Collection Rijksmuseum Kröller-Müller] is the solar disk which Delaunay was later to make into a personal emblem.)"[4][12]

The vibrating image of the Sun in Metzinger's painting, and of Delaunay's Paysage au disque (1906-1907), writes Herbert, "is an homage to the decomposition of spectral light that lay at the heart of Neo-Impressionist color theory..."[4][12]

"The Neo-Impressionists" according to Maurice Denis, "inaugurated a vision, a technique, and esthetic based on the recent discoveries of physics, on a scientific conception of the world and of life."[4][12]

In 1904-05 Henri Poincaré discovered a graphical tool for visualizing different types of polarized light (known as Poincaré sphere). The Poincaré homology sphere, also called Poincaré dodecahedral space, is a particular example of a homology sphere. Being a spherical 3-manifold, it is the only homology 3-sphere, besides the 3-sphere itself, with a finite fundamental group. While it is not known the extent to which such discoveries influenced Metzinger's representation of the radiating sun in Coucher de soleil no. 1, his interest and prowess in mathematics is well documented.[13]

Related works

J. M. W. Turner, 1839, The Fighting Temeraire, oil on canvas, 90.7 × 121.6 cm, National Gallery, London

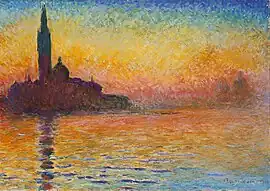

J. M. W. Turner, 1839, The Fighting Temeraire, oil on canvas, 90.7 × 121.6 cm, National Gallery, London Claude Monet, 1872, Impression, soleil levant (Impression Sunrise) oil on canvas, 48 × 63 cm, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Claude Monet, 1872, Impression, soleil levant (Impression Sunrise) oil on canvas, 48 × 63 cm, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

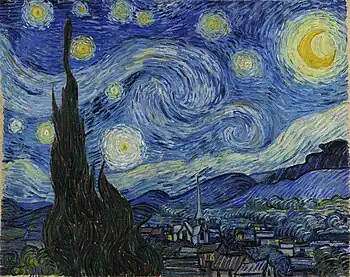

Vincent van Gogh, 1889, The Starry Night, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

Vincent van Gogh, 1889, The Starry Night, oil on canvas, 73.7 x 92.1 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York Paul Signac, 1906, La Calanque (The Bay), Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

Paul Signac, 1906, La Calanque (The Bay), Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium

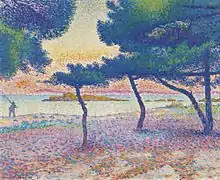

Henri-Edmond Cross, 1906–07, La baie à Cavalière, Musée de l'Annonciade, Saint-Tropez, France

Henri-Edmond Cross, 1906–07, La baie à Cavalière, Musée de l'Annonciade, Saint-Tropez, France Georges Lemmen, 1891–92, Plage à Heist (Beach at Heist), oil on wood, 37.5 x 45.7 cm, Musée d'Orsay Paris

Georges Lemmen, 1891–92, Plage à Heist (Beach at Heist), oil on wood, 37.5 x 45.7 cm, Musée d'Orsay Paris Henri-Edmond Cross, 1896, La Plage de Saint-Clair, oil on canvas, 54.5 by 65.4 cm

Henri-Edmond Cross, 1896, La Plage de Saint-Clair, oil on canvas, 54.5 by 65.4 cm

See also

References

- Jean Metzinger, Coucher de soleil, Société des artistes indépendants: catalogue de la 23ème exposition, 1907, no. 3457, p. 225

- Catalogus van de schilderijen verzameling van Mevrouw H. Kröller-Müller, Samensteller H.P. Bremmer, Published 1921(?) in 'S-Gravenhage, no. 843 (in Dutch)

- "Jean Metzinger, Coucher de soleil no. 1, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands". Archived from the original on 2013-12-17. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- Robert Herbert, Neo-Impressionism, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York, 1968, Library of Congress Card Catalogue Number: 68-16803

- Bibliotheca 1.2.7

- Homer. Iliad, 18.35

- Hesiod. Theogony, 240

- Hyginus. Fabulae, Preface.

- Apollodorus. Library, 2.1.5.

- Hyginus. Fabulae, 163.

- Joann Moser, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Pre-Cubist works, 1904–1909, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press, 1985, pp. 34-42

- Alexander Mittelmann., State of the Modern Art World, The Essence of Cubism and its Evolution in Time, 2011

- Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger: At the Center of Cubism, 1985, in Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, The University of Iowa Museum of Art