Council of Vézelay

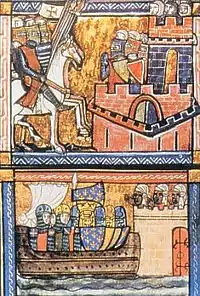

On 31 March, 1146, the French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux preached at Vézelay to encourage support for the Second Crusade.

Background

News from the Holy Land alarmed Christendom. Christians had been defeated at the Siege of Edessa and most of the area had fallen into the hands of the Seljuk Turks.[1] The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states were threatened with similar disaster. Deputations of the bishops of Armenia solicited aid from the pope, and the King of France Louis VII also sent ambassadors.[2]

Location

Vézelay's hilltop location has made it an obvious site for a town since ancient times. In the 9th century the Benedictines were given land to build a monastery during the reign of Charles the Bald.[3] According to legend, not long before the end of the first millennium a monk named Baudillon brought relics (bones) of Mary Magdalene to Vézelay from Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume.

In 1058 Pope Stephen IX confirmed the authenticity of the relics, leading to an influx of pilgrims that has continued to this day. Vézelay Abbey was also a major starting point for pilgrims on the Way of St. James to Santiago de Compostela, one of the most important of all medieval pilgrimage centres. This was crucially important in attracting pilgrims and the wealth they brought to the town.

Event

In 1144 the Pope, Eugene III commissioned French abbot Bernard of Clairvaux to preach the Second Crusade, and granted the same indulgences for it which Pope Urban II had accorded to the First Crusade.[4][2] A parliament was convoked at Vezelay in Burgundy in 1146, and Bernard preached before the assembly on March 31. Louis VII of France, his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, and the princes and lords present prostrated themselves at the feet of Bernard to receive the pilgrims' cross.[1]

The crowd was so large that a large platform was erected on a hill outside the city. The full text has not survived, but a contemporary account says that "his voice rang out across the meadow like a celestial organ"[5] When Bernard was finished the crowd enlisted en masse; they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses. Bernard is said to have flung off his own robe and began tearing it into strips to make more.[2][5] Others followed his example and he and his helpers were supposedly still producing crosses as night fell.[5]

For all his overmastering zeal, Bernard was by nature neither a bigot nor a persecutor. As in the First Crusade, the preaching inadvertently led to attacks on Jews; a fanatical French monk named Rudolf was apparently inspiring massacres of Jews in the Rhineland, Cologne, Mainz, Worms and Speyer, with Rudolf claiming Jews were not contributing financially to the rescue of the Holy Land. Bernard, the Archbishop of Cologne and the Archbishop of Mainz were vehemently opposed to these attacks, and so Bernard traveled from Flanders to Germany to deal with the problem and quiet the mobs. Bernard then found Rudolf in Mainz and was able to silence him, returning him to his monastery.[6]

The Castle of Vezelay could not contain the multitudes who thronged to hear the fervid eloquence of Bernard. The preacher, with the King of France Louis VII. by his side, who wore the cross conspicuously on his dress, ascended a platform of wood. At the close of his harangue the whole assembly broke out in tumultuous cries, " The Cross, the Cross ! " They crowded to the stage to receive the holy badge ; the preacher was obliged to scatter it among them, rather than deliver it to each. The stock at hand was soon exhausted. Bernard tore up his own dress to satisfy the eager claimants. For the first time, the two greatest sovereigns in Christendom, the Emperor and the King of France, embarked in the cause. Louis had appeared at Vezelay ; he was taking measures for the [7]

There was at first virtually no popular enthusiasm for the crusade as there had been in 1095. Bernard found it expedient to dwell upon taking the cross as a potent means of gaining absolution for sin and attaining grace. On 31 March, with King Louis VII of France present, he preached to an enormous crowd in a field at Vézelay, making "the speech of his life".[5] The full text has not survived, but a contemporary account says that "his voice rang out across the meadow like a celestial organ"[5]

James Meeker Ludlow describes the scene romantically in his book The Age of the Crusades:

A large platform was erected on a hill outside the city. King and monk stood together, representing the combined will of earth and heaven. The enthusiasm of the assembly of Clermont in 1095, when Peter the Hermit and Urban II launched the first crusade, was matched by the holy fervor inspired by Bernard as he cried, "O ye who listen to me! Hasten to appease the anger of heaven, but no longer implore its goodness by vain complaints. Clothe yourselves in sackcloth, but also cover yourselves with your impenetrable bucklers. The din of arms, the danger, the labors, the fatigues of war, are the penances that God now imposes upon you. Hasten then to expiate your sins by victories over the Infidels, and let the deliverance of the holy places be the reward of your repentance." As in the olden scene, the cry "Deus vult! Deus vult! " rolled over the fields, and was echoed by the voice of the orator: "Cursed be he who does not stain his sword with blood."[8]

When Bernard was finished the crowd enlisted en masse; they supposedly ran out of cloth to make crosses. Bernard is said to have flung off his own robe and began tearing it into strips to make more.[2][5] Others followed his example and he and his helpers were supposedly still producing crosses as night fell.[5]

Unlike the First Crusade, the new venture attracted royalty, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of France; Thierry of Alsace, Count of Flanders; Henry, the future Count of Champagne; Louis's brother Robert I of Dreux; Alphonse I of Toulouse; William II of Nevers; William de Warenne, 3rd Earl of Surrey; Hugh VII of Lusignan, Yves II, Count of Soissons; and numerous other nobles and bishops. But an even greater show of support came from the common people. Bernard wrote to the pope a few days afterwards, "Cities and castles are now empty. There is not left one man to seven women, and everywhere there are widows to still-living husbands."[2]

Notes

- Riley-Smith 1991, p. 48.

- Durant (1950) p.594.

- Jaucourt, Louis, chevalier de. "Vézelay." The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Warren Roby. Ann Arbor: Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library, 2007. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.did2222.0000.765 (accessed April 1, 2015). Originally published as "Vézelay," Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 17:226–227 (Paris, 1765).

- Bunson 1998, p. 130.

- NORWICH, JOHN JU (2012). The Popes: A History. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099565871.

- Tyerman 2006, pp. 281–288.

- Milman, Henry Hart (1854). HISTORY OF LATIN CHRISTIANITY. p. 652.

- Ludlow 1896, pp. 164–167.

References

- Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret; Bunson, Stephen (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints. Huntington: Our Sunday Visitor. ISBN 978-0-87973-588-3.

- Baldwin, Mrshall W.; Setton, Kenneth M. (1969). A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Barraclough, Geoffrey (1984). The Origins of Modern Germany. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-393-30153-3.

- Brundage, James (1962). The Crusades: A Documentary History. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: Marquette University Press.

- Christiansen, Eric (1997). The Northern Crusades. London: Penguin Books. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-14-026653-5.

- Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1365. ISBN 978-0-06-097468-8.

- Herrmann, Joachim (1970). Die Slawen in Deutschland. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag GmbH. p. 530.

- Ludlow, James Meeker (1896). The Age of the Crusades. Christian Literature Company.

- Nicolle, David (2009). The Second Crusade 1148: Disaster outside Damascus. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-354-4.

- Norwich, John Julius (1995). Byzantium: the Decline and Fall. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-82377-2.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1991). Atlas of the Crusades. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9780816021864.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A Short History (Second ed.). New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10128-7.

- Runciman, Steven (1952). A History of the Crusades, vol. II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187 (repr. Folio Society, 1994 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- William of Tyre; Babcock, E. A.; Krey, A. C. (1943). A History of Deeds Done Beyond the Sea. Columbia University Press. OCLC 310995.