Lead (leg)

Lead refers to which set of legs, left or right, leads or advances forward to a greater extent when a quadruped animal is cantering, galloping, or leaping. The feet on the leading side touch the ground forward of its partner. On the "left lead", the animal's left legs lead. The choice of lead is of special interest in horse riding.

A lead change refers to an animal, usually a horse, moving in a canter or gallop, changing from one lead to the other. There are two basic forms of lead change: simple and flying. It is very easy to define the correct lead from the incorrect lead. When a horse is executing the correct lead, the inside front and hind legs reach farther forward than the outside legs.

In a transverse or lateral or united canter and gallop, the hind leg on the same side as the leading foreleg (the lateral hindleg) advances more.[1] In horses this is the norm.

In a rotatory or diagonal or disunited canter and gallop, the hind leg on the opposite side (the diagonal hindleg) advances more.[1] In horses, it is more often than not an undesirable gait form, also known as rotary and round galloping, and as moving disunited, cross-firing, and cross-cantering. In animals such as dogs, deer, and elk, however, this form of the gait is the norm.[1]

Some authorities define the leading leg in the singular form as the last to leave the ground before the one or two periods of suspension within each stride.[2] In these cases, because the canter has only one moment of suspension, the leading leg is considered to be the foreleg. Because in some animals the gallop has two moments of suspension, some authorities recognize a lead in each pair of legs, fore and hind. So when an animal is in a rotatory gait, it is called disunited,[2] due to different leading legs in the front and hind.

Usage in horse sports

A horse is better balanced when on the correct lead of the canter, that is to say, the lead which corresponds to the direction of travel. If a horse is on the wrong lead, it may be unbalanced and will have a much harder time making turns. However, there is an exception to this general rule, the counter canter, or counter-lead, a movement used in upper-level dressage, where a horse may be deliberately asked for what would normally be the "wrong" lead in order to show obedience and balance.

Transverse canter

The standard canter is movement where the horse travels in a transverse canter bent slightly in the direction of the leading inside front and rear legs. In standard horse show competition, travel on the inside "lead" is almost always considered correct, and horses on the outside lead or those performing a disunited (rotatory) canter are penalized. The only exceptions are when a counter-canter is specifically requested, or in some timed events where leads are not evaluated.

Hand gallop

In equestrian competition, a show ring "hand gallop," or "gallop in hand" is a true lengthening of stride. However, the horse remains in control and excess speed is penalized. Usually the constraints of a show arena and the presence of other animals prevent the gait from extending into the four-beat form of the racing gallop.

Counter canter

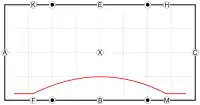

The counter-canter is a movement in which the animal travels a curved path on the outside transverse lead. For example, while on a circle to the left, the horse is on the right lead. When performing a counter-canter, the horse is slightly bent in the direction of the leading legs, but opposite to the line of travel.

The counter-canter is primarily used as a training movement, improving balance, straightness, and attention to the aids. It is used as a stepping-stone to the flying lead change. It is also a movement asked for in upper level dressage tests.

Most riders begin asking for the counter-canter by riding through a corner on the inside lead, then performing a very shallow loop on the long side of the arena, returning to the track in counter-canter. As the horse becomes better at the exercise, the rider may then make the loop deeper, and finally perform a 20-meter circle in counter-canter.

In polo, the counter canter is often used in anticipation of a sudden change of direction. For example, the horse travels a large arc to the right while staying on the left lead, then suddenly turns sharply to the left with a burst of speed and on the correct lead.

Rotatory canter and gallop

In the rotatory gait, often called "cross-firing," "cross-cantering," or a "disunited canter," the horse balances in beat two on both legs on one side of its body, and in beats one and three on the other side. This produces a distinctive rotary or twisting motion in the rider's seat. For the majority of horses and riders this rotary motion is awkward, unbalanced and could be dangerous.[3][4] Eadweard Muybridge illustrated both rotatory and transverse canters but did not stress the difference of lead.[2]

In equestrian disciplines in which gait is judged, the rotatory canter (called disunited canter or cross-canter in most rule books) is considered a fault and penalized.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20] However, in horse racing, the rotatory gallop (there often called round gallop) not only is common at the start of races but also is about 5 miles per hour faster than the transverse gallop.[21]

Lead change

Lead changes are important in many riding disciplines. In horse racing, when a horse is galloping, the leading leg may tire, resulting in the horse slowing down. If the lead is changed, the horse will usually "find another gear" or be able to maintain its pace. Because horses race counter-clockwise in North America, a racehorse is usually trained to lead with the left leg while rounding the turn for balance, but switch to the right lead on the straightaways between the turns to rest the left

Changes of lead are asked for in some dressage tests, and in the dressage phase of eventing. Degree of difficulty increases with each level, from simple changes, to single flying changes, to multiple flying changes within fewer and fewer strides (known in this context as tempi changes). They are judged on their smoothness, promptness, and the submission of the horse.

In reining and working cow horse flying lead changes are an integral part of nearly all patterns except for those at the most novice levels. They performed as part of a pattern, usually in a figure eight, and illustrate a high degree of training and responsiveness. A good flying lead change appears effortless both in the horse's actions and in the rider's cues. The horse will not speed up or slow down or display resentment (i.e. by switching its tail excessively) or hesitation. Controlled speed is desired in reining competition, and the faster a horse moves while properly executing the flying change, the higher the score.

In jumping, including show jumping, eventing, and hunter competition, the flying change is essential, as a horse on the incorrect lead may become unbalanced on the turn, and then have an unbalanced take-off and may hit a rail. It is also possible that the horse will fall should he be asked to make a tight turn. For show hunters, a horse is penalized for a poor or missed flying change. In show jumping and the eventing jumping phases, the flying change is not judged, but correct leads are recommended should the rider wish to stay balanced enough to jump each fence with the horse's maximum power and agility.

Simple change

The simple change is a way to change leads on a horse that has not yet learned how to perform a flying change. In most cases, riders change leads by performing a few steps of the trot, before coming back to the opposite lead of the canter. However, a true simple change asks for the horse to perform a canter-walk (or halt)-canter transition. This requires more balance from the horse, and more finesse in timing the aids from the rider. Simple changes going through the walk are used as stepping stones for the flying change, asking the horse for more self-carriage that is needed for the flying change. The canter-halt-canter transition is becoming more and more popular, especially at the higher levels of competition, where judges are now beginning to specify a simple change through the halt, as it requires a greater degree of control by the rider and balance by the horse.

Flying change

The flying change is a lead change performed by a horse in which the lead changes at the canter while in the air between two strides. It is often seen in dressage, where the horse may do several changes in sequence (tempi changes), in reining as part of the pattern, or in jumping events, where a horse will change lead as it changes direction on the course.

Tempi changes

While a single change is often performed to change direction, dressage competition adds tempi changes at the upper levels. Tempi changes are very difficult movements, as the horse is required to perform multiple flying changes in a row. In a test, tempi changes may requested every stride (one-tempis), every two strides (two tempis), three strides (threes), or four strides (fours). The number of strides per change asked in tests begins at four, to give the horse and rider more time to prepare, and as the horse and rider become more proficient the number decreases to one-tempis. When a horse performs one-tempi changes, it often looks as if it is skipping.[22] They may be performed across the diagonal or on a circle.

Comparison of transverse and rotatory gaits

These tables outline the sequence of footfalls (beats) in the canter and gallop, the animal on the right lead.

Canter

| Stride | Transverse | Rotatory |

|---|---|---|

| Footfall 1 | Left hind | Right hind |

| Footfall 2 | Left fore and right hind | Left fore and left hind |

| Footfall 3 | Right fore | Right fore |

| Suspension |

Gallop

| Stride | Transverse | Rotatory |

|---|---|---|

| Footfall 1 | Left hind | Right hind |

| Footfall 2 | Right hind | Left hind |

| Suspension (in some animals) | ||

| Footfall 3 | Left fore | Left fore |

| Footfall 4 | Right fore | Right fore |

| Suspension |

See also

References

- Tristan David Martin Roberts (1995) Understanding Balance: The Mechanics of Posture and Locomotion, Nelson Thornes, ISBN 0-412-60160-5.

- Eadweard Muybridge, edited by Lewis S. Brown (1955) Animals in motion, Courier Dover Publications, 74 pages, ISBN 0-486-20203-8.

- "Gaits in General for Dressage: Math & Variations on a Theme of Walk, Trot, Canter (or, Why the Old Classical Masters Were Right)" Archived 2004-08-23 at archive.today Web page accessed April 5, 2008

- Ziegler, Lee. "What is a Canter?" Web site accessed April 5, 2008

- USEF Welch pony division rules requires ponies to be straight on both leads

- USEF Hunter division penalizes missed lead changes

- Friesian division requires horses to be straight and correct on both leads

- Equitation division requires correct leads

- Dressage division describes correct canter footfall pattern, requiring front and read footfalls to lead

- Arabian division requires correct and straight on both leads

- Saddlebred division requires correct leads, explicitly penalizes cross-cantering

- Andalusian/Lusitano division requires correct and straight on both leads

- Reining division penalizes out of lead 1 point for every 1/4 of a circle

- Paso Fino Division requires true three beat canter, true and straight on both leads

- National Show horse division requires true and straight on both leads, singles out cross-cantering

- Morgan division requires canter true and straight on both leads

- Western division penalizes cross-cantering, not changing leads simultaneously and requires correct leads

- National Reining Horse Association Archived 2006-11-14 at the Wayback Machine General rules for Judging, penalizes failure to change front and back leads

- United States Dressage Federation describes and defines disunited canter.

- American Quarter Horse Association Rule Book Archived 2008-05-13 at the Wayback Machine explicitly penalizes cross-cantering in several events (including Working Hunter, Western Riding, and Equitation) plus 62 other references to being correct and straight on both leads)

- Rooney, James DVM (1998) The lame horse, The Russell Meerdink Company Ltd., 261 pages, ISBN 0-929346-55-6.

- "To see one-tempis on video, see". Archived from the original on 2010-07-31. Retrieved 2011-01-18.