Court of labour (Belgium)

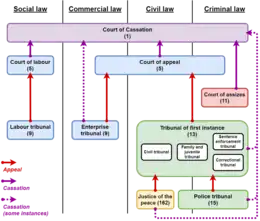

The court of labour (Dutch: arbeidshof, French: cour du travail, German: Arbeitsgerichtshof) is the appellate court in the judicial system of Belgium which hears appeals against judgements of the labour tribunals and the presidents of those tribunals in their respective judicial area. There are five courts of labour for each of the five judicial areas (Antwerp, Brussels, Ghent, Liège and Mons), which are the largest geographical subdivisions of Belgium for judicial purposes. Some of the courts of labour hear cases in multiple seats. Further below, an overview is provided of the five courts of labour and their seats. Whilst their territorial organisation is the same, the courts of labour are separate from the courts of appeal, which are the main appellate courts in Belgium.[1][2]

|

|---|

|

|

The organisation of the courts of labour and the applicable rules of procedure are laid down in the Belgian Judicial Code. The language in which the proceedings of the courts of labour are held depends on the official languages of their judicial areas: Dutch for the courts of labour of Antwerp and Ghent, Dutch and French for the court of labour of Brussels, French for the court of labour of Mons, and French and German for the court of labour of Liège. The use of languages in judicial matters is a sensitive topic in Belgium, and is strictly regulated by the law.[1][2][3]

Court structure

A judge in the court of labour is called a counsellor (Dutch: raadsheer, French: conseiller, German: Gerichtsrat). They are professional, law-trained magistrates who are, like all judges in Belgium, appointed for life until their retirement age. Lawyers or notaries can act as locum tenens counsellor. There are also lay judges in the courts of labour, who are called social counsellors (Dutch: raadsheer in sociale zaken, French: conseiller social, German: Sozialgerichtsrat). These social counsellors are labourers, employees, employers or self-employed who are appointed by the federal government for a tenure of five years, on the advice of employers' organisations and trade unions. Appellate cases are heard by the different chambers of the courts of labour, which are chaired by a panel consisting of a counsellor assisted by two or four social counsellors (depending on the nature and complexity of the case), assisted by a clerk. Both claimants and defendants in a case can be assisted or represented by counsel, but this is not required. In addition, labourers and employees can be represented by a union representative with power of attorney.[1][2][4]

The counsellor, who chairs the panel, is referred to as the 'president of the chamber' or 'chairman of the chamber' (Dutch: kamervoorzitter, French: président de chambre, German: Kammerpräsident). The counsellor who holds the overall leadership position of the court of appeal is referred to as the 'first president' or 'first chairman' (Dutch: eerste voorzitter, French: premier président, German: erster Präsident). A judgement made by a court of labour is literally called an 'arrest' (Dutch: arrest, French: arrêt, German: Entscheid) in order to distinguish it from the judgements of lower tribunals; it might also be translated into English as a 'decision' or 'ruling'. For the sake of readability, the term 'judgement' will be used in this article.[1][2][4]

There is a public prosecutor's office attached to each court of labour; these are referred to as an auditorate-general (Dutch: auditoraat-generaal, French: auditorat général, German: Generalauditorat). An auditorate-general is led by the prosecutor-general (Dutch: procureur-generaal, French: procureur général, German: Generalprokurator), who also leads the prosecutor-general's office attached to the corresponding court of appeal. The auditorate-general has duties in both criminal and non-criminal cases; they advise the court of labour in non-criminal social cases (in some cases related to social security or social benefits, this advice is mandatory), and prosecute (suspected) offenders in social-criminal cases before the courts of appeal.[1][2]

Jurisdiction

The courts of labour have appellate jurisdiction over all judgements made in first instance by the labour tribunals and the presidents of those tribunals in their respective judicial areas. All judgements of the labour tribunals are open for appeal; there are no exceptions for specific or petty cases.[5]

Appeal in cassation

The judgements made by the courts of labour are final as to questions of fact. Only an appeal in cassation on questions of law to the Court of Cassation, the supreme court in the judicial system of Belgium, is still possible. Such an appeal to the Court of Cassation is extraordinary procedure, and will result in the Court of Cassation either upholding or either quashing the contested judgement of the court of labour. If the Court of Cassation does the latter, it will refer the case to a different court of labour than were the case originated from, to be tried de novo (both on questions of fact and questions of law).

Statistics

According to the statistics provided by the College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium, a total of 4,292 cases were opened at all courts of labour in 2017, aside from 6,428 cases that were still pending from before January 2017. In 4,474 of these cases, a final judgement was rendered by the courts of labour in 2017 and these cases were therefore closed.[6]

observer>———>

As of 2018, there is a seat of a court of labour in the following municipalities:

Seats of the court of labour of Antwerp:

- Antwerp (with jurisdiction over the province of Antwerp)

- Hasselt (with jurisdiction over the province of Limburg)

Seats of the court of labour of Brussels:

Seats of the court of labour of Ghent:

- Bruges (with jurisdiction over the province of West Flanders)

- Ghent (with jurisdiction over the province of East Flanders)

Seats of the court of labour of Liège:

- Liège (with jurisdiction over the province of Liège)

- Namur (with jurisdiction over the province of Namur)

- Neufchâteau (with jurisdiction over the province of Luxembourg)

Seats of the court of labour of Mons:

See also

References

- "Arbeidshof" [Court of labour]. www.rechtbanken-tribunaux.be (in Dutch). College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Judiciary – Organization" (PDF). www.dekamer.be. Parliamentary information sheet № 22.00. Belgian Chamber of Representatives. 1 June 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Judiciary – Breakdown of law" (PDF). www.dekamer.be. Parliamentary information sheet № 21.00. Belgian Chamber of Representatives. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Articles 103, 104 & 106–113 of the Belgian Judicial Code". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Articles 607 & 617 of the Belgian Judicial Code". www.ejustice.just.fgov.be (in Dutch). Belgian official journal. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Kerncijfers van de gerechtelijke activiteit – Jaren 2010-2017" [Key figures of judicial activity – Years 2010-2017] (PDF). www.tribunaux-rechtbanken.be (in Dutch). College of the courts and tribunals of Belgium. August 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2019.