Creede, Colorado

Creede is a Statutory Town and the county seat of Mineral County, Colorado, United States. It is the most populous community and the only incorporated municipality within the county.[1] The town population was 257 at the 2020 United States census.[4]

Creede, Colorado | |

|---|---|

Downtown Creede (2005) | |

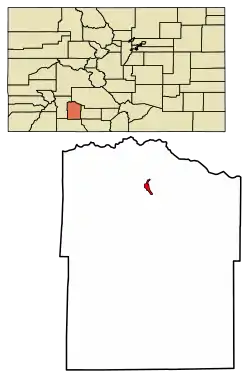

Location of the City of Creede in the Mineral County, Colorado. | |

Creede Location of the City of Creede in the United States. | |

| Coordinates: 37°50′57″N 106°55′31″W[2] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Mineral County seat[1] |

| Incorporated | May 19, 1892[3] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Statutory Town[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.950 sq mi (2.460 km2) |

| • Land | 0.950 sq mi (2.460 km2) |

| • Water | 0.000 sq mi (0.000 km2) |

| Elevation | 8,799 ft (2,682 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 257 |

| • Density | 377/sq mi (146/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−07:00 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−06:00 (MDT) |

| ZIP Code[6] | 81130 |

| Area code | 719 |

| FIPS code | 08-14765 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2412384 |

| Website | City website |

History

Travelers to this area appeared in the early 19th century. Tom Boggs, a brother-in-law of Kit Carson, farmed at Wagon Wheel Gap in the summer of 1840. The first silver discovery was made at the Alpha mine in 1869, but the silver could not be extracted at a profit from the complex ores. Ranchers and homesteaders moved in when stagecoach stations (linking the mining operations over the Divide with the east) were built in the 1870s, but the great "Boom Days" started with the discovery of rich minerals in Willow Creek Canyon in 1889.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

Creede was the last silver boom town in Colorado in the 19th century. The town leapt from a population of 600 in 1889 to more than 10,000 people in December 1891. The Creede mines operated continuously from 1890 until 1985, and were served by the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad.[13]

The original townsite of Creede was located on East Willow Creek just above its junction with West Willow Creek. Below Creede were Stringtown, Jimtown, and Amethyst. The Willow Creek site was soon renamed Creede after Nicholas C. Creede who discovered the Holy Moses Mine. Soon the entire town area from East Willow to Amethyst was called Creede.[14][15]

While Creede was booming, the capital city of Denver, Colorado was experiencing a reform movement against gambling clubs and saloons. Numerous owners of gambling houses in Denver relocated to Creede's business district. One of these was confidence man Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith. Soapy became the uncrowned king of Creede's criminal underworld, and opened the Orleans Club. Other famous people in Creede were Robert Ford (the man who killed outlaw Jesse James), Bat Masterson, and William Sidney "Cap" Light (the first deputy sheriff in Creede, and brother-in-law of Soapy Smith). On June 5, 1892 a fire destroyed most of the business district. Three days later, on June 8, Ed O'Kelley walked into Robert Ford's makeshift tent-saloon and shot him dead.[16][17] The town of Creede was incorporated on June 13, 1892. The anti-gambling movement in Denver had ceased, and the Denver businessmen moved back to their former areas of operation.[18]

Creede's boom lasted until 1893, when the Silver Panic hit the silver mining towns in Colorado. The price of silver plummeted, and most of the silver mines were closed.[19][20] Creede never became a ghost town, although the boom was over and its population declined. After 1900, Creede stayed alive by relying increasingly on lead and zinc in the ores.[21][22][23] Total production through 1966 was 58 million troy ounces (870 metric tons) of silver, 150 thousand ounces (4.7 metric tons) of gold, 112 thousand metric tons of lead, 34 thousand metric tons of zinc, and 2 million metric tons of copper.[24]

Geography

Creede is located near the headwaters of the Rio Grande, which flows through the San Juan Mountains and the San Luis Valley on its way to New Mexico, Texas, and eventually into the Gulf of Mexico.

The river has played a critical role in the development of farming and ranching in the Valley. The Rio Grande and its tributary trout streams provide excellent opportunities for fly fishermen and its unspoiled headwaters in the Weminuche Wilderness are a favorite for hikers.

At the 2020 United States Census, the town had a total area of 608 acres (2.460 km2) , all of it land.[4]

Climate

| Climate data for Creede, Colorado, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 2007–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

56 (13) |

66 (19) |

73 (23) |

79 (26) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

88 (31) |

86 (30) |

80 (27) |

77 (25) |

58 (14) |

91 (33) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.9 (0.5) |

37.6 (3.1) |

45.9 (7.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

63.2 (17.3) |

74.8 (23.8) |

78.9 (26.1) |

75.0 (23.9) |

70.1 (21.2) |

60.7 (15.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

32.6 (0.3) |

56.0 (13.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 11.6 (−11.3) |

16.6 (−8.6) |

28.2 (−2.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

45.0 (7.2) |

53.6 (12.0) |

59.7 (15.4) |

57.5 (14.2) |

51.0 (10.6) |

40.4 (4.7) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

12.5 (−10.8) |

36.7 (2.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | −9.8 (−23.2) |

−4.3 (−20.2) |

10.5 (−11.9) |

20.6 (−6.3) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

32.5 (0.3) |

40.4 (4.7) |

40.1 (4.5) |

32.0 (0.0) |

20.2 (−6.6) |

8.0 (−13.3) |

−7.6 (−22.0) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −40 (−40) |

−31 (−35) |

−18 (−28) |

1 (−17) |

8 (−13) |

16 (−9) |

23 (−5) |

23 (−5) |

19 (−7) |

−8 (−22) |

−13 (−25) |

−42 (−41) |

−42 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.84 (21) |

0.76 (19) |

0.97 (25) |

1.05 (27) |

1.02 (26) |

0.82 (21) |

2.03 (52) |

2.73 (69) |

1.74 (44) |

1.29 (33) |

1.22 (31) |

0.66 (17) |

15.13 (385) |

| Source 1: NOAA[25] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[26] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 938 | — | |

| 1910 | 741 | −21.0% | |

| 1920 | 500 | −32.5% | |

| 1930 | 384 | −23.2% | |

| 1940 | 670 | 74.5% | |

| 1950 | 503 | −24.9% | |

| 1960 | 350 | −30.4% | |

| 1970 | 653 | 86.6% | |

| 1980 | 610 | −6.6% | |

| 1990 | 362 | −40.7% | |

| 2000 | 377 | 4.1% | |

| 2010 | 290 | −23.1% | |

| 2020 | 257 | −11.4% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census | |||

As of the census[27] of 2000, there were 377 people, 181 households, and 106 families residing in the town. The population density was 622.4 inhabitants per square mile (240.3/km2). There were 275 housing units at an average density of 454.0 per square mile (175.3/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 96.82% White, 1.33% Native American, and 1.86% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.59% of the population.

There were 181 households, out of which 19.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 46.4% were married couples living together, 8.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 41.4% were non-families. 33.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08 and the average family size was 2.70.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 19.1% under the age of 18, 5.0% from 18 to 24, 26.3% from 25 to 44, 33.7% from 45 to 64, and 15.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 100.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 98.1 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $30,893, and the median income for a family was $34,125. Males had a median income of $27,250 versus $17,250 for females. The per capita income for the town was $21,801. About 12.2% of families and 13.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.0% of those under age 18 and 11.1% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

The Creede Fork, also known as the World's Largest Fork, is a 40-foot aluminum sculpture and roadside attraction in Creede built in 2012.[28] It is the largest fork in the United States, beating out the 35-foot-long (11 m) fork in Missouri that previously held the record.[29] Created by artists Chev and Ted Yund, the fork is made of aluminum and weighs over 600 pounds (270 kg).[30] In January 2018, it was named by The Daily Meal as the weirdest tourist attraction in Colorado.[31]

The fork was commissioned by Keith Siddel as a birthday present for his wife, Denise Dutwiler. Siddel hired two local artists, Chev and Ted Yund, to create the structure. The fork was designed specifically to out-measure the Giant Fork in Springfield, Missouri, which previously held the record of being the longest fork in the United States at a length of 35 feet.[32]

The Creede Repertory Theatre was founded in 1966 and features plays.

In popular culture

Poet and journalist Cy Warman wrote two poems about Creede, Creede[33] and The Rise and Fall of Creede.[34]

The gambler Poker Alice lived for a time in Creede as well as several other locations in Colorado.

In the 1976 film The Shootist, terminally ill gun fighter J.B. Books (portrayed by John Wayne) relates that he had just seen a "sawbones" (slang for a doctor or surgeon) in Creede when questioned about his symptoms.

The final scene in the 2007 drama The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (as well as the real-life event it depicts) takes place in a saloon in Creede, where Robert Ford is gunned down by Edward O'Kelley 10 years after Ford killed Jesse James. The scene itself was shot on a $1 million set in Alberta that recreated much of 19th century Creede.

Scenes from the 2013 action Western film Lone Ranger were filmed in locations in and around Creede. The train scene was filmed on trains belonging to Creede Railroad Company.

The 2017 Netflix drama Godless takes place partly in Creede. It is the site of a train robbery, after which the entire town is massacred by the criminal gang responsible.

See also

References

- "Active Colorado Municipalities". Colorado Department of Local Affairs. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- "2014 U.S. Gazetteer Files: Places". United States Census Bureau. July 1, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2015.

- "Colorado Municipal Incorporations". State of Colorado, Department of Personnel & Administration, Colorado State Archives. December 1, 2004. Retrieved September 2, 2007.

- "Decennial Census P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data". United States Census Bureau, United States Department of Commerce. August 12, 2021. Retrieved September 4, 2021.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "ZIP Code Lookup". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original (JavaScript/HTML) on November 4, 2010. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- Williams Jr., Albert (June 1892). "Creede, A New Mining Camp". The Engineering Magazine. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Publishing Co. III (3): 324–339. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "Congress and Silver". The Illustrated American. X (108): 158. March 12, 1893. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "Creede, the New Mining Town of Colorado". Scientific American. New York, NY: Munn & Co. LXVI (13): 196–197. March 26, 1892. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Hall, Frank (1895). History of the State of Colorado. Vol. IV. Chicago, IL: The Blakely Printing Company. pp. 223–225. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "Creede Is A Lively Town: Thousands Rush In For Sale Of Lands" (PDF), New York Times, February 27, 1892, retrieved May 16, 2012

- "Creede, the New Mining Town of Colorado". Scientific American. New York, NY: Munn & Company. LXVI (13): 196–197. March 26, 1892. Retrieved May 17, 2012.

- "History". www.creede.com. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- "Creede". The Colorado Magazine. Denver, CO: The Colorado Publishing Co. 1 (2): 163–172. May 1893. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Hall, Henry, ed. (1896). America's Successful Men of Affairs (entry for Nicholas C. Creede). Vol. II. New York, NY: The New York Tribune. p. 212. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Warman, Cy (1898). Frontier Stories, "A Quiet Day In Creed". New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 93–101. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- The Wild Bandits of the Border. Chicago, IL: Laird & Lee. 1893. pp. 355–363. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Davis, Richard Harding (1892). The West From A Car-Window (Chapter III, At A New Mining Camp) (1 ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Brothers. pp. 59–90. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "The Silver Situation in Colorado". The Review of Reviews. New York, NY. VIII (3): 277–280. September 1893. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "There May Be Trouble At Creede: Land Seized on the Old Site of Jimtown" (PDF), New York Times, May 26, 1895, retrieved May 16, 2012

- Lakes, Arthur (May 1903). "Creede Mining Camp: Valuable Mines Operated Through the Nelson and Humphreys Tunnels". Mines and Minerals. Scranton, PA: International Textbook Co. XXIII (10): 433–435. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Parmelee, H.C. (December 1910). "Zinc Ore Dressing in Colorado - III". Metallurgical and Chemical Engineering. New York, NY: Electrochemical Publishing Co. VIII (12): 677–680. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- "The Western Metallurgical Field: New Source of Sulphur in Colorado". Metallurgical and Chemical Engineering. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. XVII (9): 523. November 1, 1917. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- Henry C. Meeves and Richard P. Darnell (1968) Study of the Silver Potential, Creede District, Mineral County, Colorado, US Bureau of Mines, Information Circular 8370.

- "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Creede WTP, CO". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Pueblo". National Weather Service. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Creede Fork - Creede, CO". facebook.com. Facebook. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- "12 Quirky Roadside Attractions in Colorado". colorado.com. Colorado Tourism Office. August 7, 2017.

- "Creede, Colorado: Largest Fork in the U.S." RoadsideAmerica.com. Roadside America.

- Rose, Lily (January 20, 2018). "The Weirdest Tourist Attraction in Every State". thedailymeal.com. The Daily Meal.

- Cook, Terry (May 31, 2016). "Only in Colorado: The World's Largest Fork". 5280.com. 5280 Publishing.

- "Poem: Creede by Cy Warman".

- "Poem: The Rise and Fall of Creede by Cy Warman".

Further reading

- "Creede Camp in Ruins: A Young Colorado Mining Town Visited by Fire, The Losses Count Up in the Millions, Many Houses were Blown Up with Giant Powder in the Vain Hope of Staying the Flames", San Francisco Call, vol. 72, no. 6, p. 2, June 6, 1892, retrieved May 19, 2012