Creedmoor Psychiatric Center

Creedmoor Psychiatric Center is a psychiatric hospital at 79-26 Winchester Boulevard in Queens Village, Queens, New York, United States. It provides inpatient, outpatient and residential services for severely mentally ill patients. The hospital occupies more than 300 acres (1.2 km2) and includes more than 50 buildings.[1]

| Creedmoor Psychiatric Center | |

|---|---|

Winchester Boulevard entrance | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Queens Village, Queens, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 40°44′29″N 73°43′54″W |

| Organization | |

| Care system | Medicaid, private |

| Type | Specialist |

| Network | New York State Office of Mental Health |

| Services | |

| Speciality | Psychiatry |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in New York |

| Other links | Hospitals in Queens |

The site was named after the Creed family, which farmed on the site. It later was used as a firing range from the 1870s until 1892. The Farm Colony of Brooklyn State Hospital was opened on the site in 1912, with 32 patients. By 1959, the hospital housed 7,000 inpatients. The hospital's census declined by the early 1960s, and unused portions were sold off and developed into the Queens County Farm Museum, a school campus, and a children's psychiatric center.

History

Site

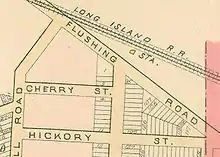

The hospital's name derives from the Creeds, a family that previously farmed the site. The local railroad station on a line that ran from Long Island City to Bethpage took the name Creedmoor, apparently from the phrase "Creed's Moor," describing the local geography,[2] In the early 1870s, New York State paid easement for the railway for the land from the Creeds later used by the National Guard and by the National Rifle Association of America (NRA) as a firing range. The Creedmoor Rifle Range hosted prestigious international shooting competitions, which became the forerunner of the Palma Trophy competition.[3] In 1892, as a result of declining public interest and mounting noise complaints from the growing neighborhood, the NRA deeded its land back to the state.[3]

Hospital

In 1912, the Farm Colony of Brooklyn State Hospital was opened, with 32 patients, at Creedmoor by the Lunacy Commission of New York State, reflecting a trend towards sending the swelling population of urban psychiatric patients to the fresh air of outlying areas. By 1918, Creedmoor's own census had swollen to 150, housed in the abandoned National Guard barracks. By 1959, the hospital housed 7,000 inpatients.[2] Creedmoor is described as a crowded, understaffed institution in Susan Sheehan's Is There No Place On Earth For Me? (1982), a biography of a patient pseudonymously called Sylvia Frumkin. Dr. Lauretta Bender, child neuropsychiatrist, has been reported as practicing there in the 1950s and 1960s. In the late 1970s, one of its more notorious patients was former NYPD officer Robert Torsney, who was committed there in December 1977 after being found not guilty by reason of insanity in the 1976 murder of then 15-year-old Randolph Evans in Brooklyn and was kept there until July 1979 when reviewers declared him no longer a threat.

The hospital's census had declined by the early 1960s, as the introduction of new psychiatric medications, along with the deinstitutionalization movement for many psychiatric patients, led to declining patient populations. In 1975, the land in Glen Oaks formerly used to raise food for the hospital was opened to the public as the Queens County Farm Museum.[4] Another part of the campus in Glen Oaks was developed into the Queens Children's Psychiatric Center.[5] In 2004, the remaining part of Creedmoor land in Glen Oaks was developed into the Glen Oaks public school campus, including The Queens High School of Teaching. By 2006, other parts of the Creedmoor campus had been sold and the inpatient census was down to 470.[2] A more recent portrayal of life in Creedmoor appears in Katherine Olson's Something More Wrong (2013).[6]

There are several unused buildings on the property, including the long-abandoned Building 25. Many parts of the building are covered in bird guano, the largest pile being several feet high.[7] In August 2023, a shelter for migrants opened at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center, amid a sharp increase in the number of asylum seekers traveling to the city.[8][9]

Notable residents

Rock musician Lou Reed, jazz pianist Bud Powell and former New York City police officer Robert Torsney, were treated at Creedmoor.[10] Legendary folksinger Woody Guthrie, who had been institutionalized for years with Huntington's disease, was transferred to Creedmoor in June 1966 and died there in October 1967.[11] Hungarian composer Paul Abraham spent ten years in Creedmoor from 1946 until 1956. George Metesky, better known as the Mad Bomber, spent the last months of his 17-year involuntary commitment at Creedmoor in 1973.[12][13] Simone D. is a pseudonym for a psychiatric patient at Creedmoor,[14] who in 2007 won a court ruling which set aside a two-year-old court order to give her electroshock treatment against her will.[15][16]

Programs

The hospital's notable ventures include The Living Museum, which showcases artistic works by patients and is the first museum of its kind in the U.S.[17]

References

- Creedmoor Psychiatric Center. Retrieved April 15, 2015

- Queens Children's Psychiatric Center-History Archived January 28, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 15, 2015

- Creedmoor Shooting Range History Archived April 15, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 15, 2015

- "Queens County Farm Museum". Queens County Farm Museum. March 6, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- Queens Children's Psychiatric Center. Retrieved April 15, 2015

- Creedmoor Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 5, 2016

- "Inside Creedmoor State Hospital's Building 25". AbandonedNYC. May 31, 2012. Archived from the original on June 17, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- Balk, Tim (August 15, 2023). "NYC opens huge migrant tent shelter at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- "Migrant relief center opens at Creedmoor Psychiatric Center". Spectrum News NY1. August 15, 2023. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Levy, Aidan (October 1, 2015). Dirty Blvd.: The Life and Music of Lou Reed. Chicago Review Press. p. 52. ISBN 9781613731093. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- Guthrie, Nora (October 30, 2012). My Name is New York: Ramblin' Around Woody Guthrie's Town. powerHouse Books. p. 81. ISBN 9781576876343. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- "' Mad Bomber' Due For Court Hearing; It Could Free Him". The New York Times. September 26, 1973. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Kaufman, Michael T (December 13, 1973). "'Mad Bomber,' Now 70, Goes Free Today". The New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Ussher, Jane M. (2011). The Madness Of Women: Myth and Experience. Routledge. p. 85. ISBN 9781136656323.

- "MindFreedom, article title Another victory against forced electroshock. Simone D. wins!". MFIPortal. July 7, 2007. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- "New York's High Court Condones Shocking Injustice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- "MentalWellness: Online schizophrenia resource and information about mental health issues". September 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

External links

- Official website Creedmoors official page at the New York State Office of Mental Health

- Goode, Erica (July 30, 2002). "A CONVERSATION WITH: Janos Marton; A Protected Space, Where Art Comes Calling". New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Creedmoor's Living Museum documentary

- Queens Library. 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161223063529/http://www.queensmemory.org/index.php/Search/Index/search/Creedmoor+Psychiatric+Center "Creedmoor Psychiatric Center." Queens Memory. Accessed December 22.

- Olson, Katherine B. Something More Wrong The Big Roundtable, July 25, 2013. Accessed June 5, 2016

- Lambert, Bruce (November 5, 1996). "Long Island Debates Future of Psychiatric Hospitals". New York Times. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

- Photographs from Inside Creedmor's abandoned Building 25