Triturus

Triturus is a genus of newts comprising the crested and the marbled newts, which are found from Great Britain through most of continental Europe to westernmost Siberia, Anatolia, and the Caspian Sea region. Their English names refer to their appearance: marbled newts have a green–black colour pattern, while the males of crested newts, which are dark brown with a yellow or orange underside, develop a conspicuous jagged seam on their back and tail during their breeding phase.

| Triturus Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Marbled newt | |

| |

| Northern crested newt | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Amphibia |

| Order: | Urodela |

| Family: | Salamandridae |

| Subfamily: | Pleurodelinae |

| Genus: | Triturus Rafinesque, 1815[2] |

| Type species | |

| Triturus cristatus (Laurenti, 1768) | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Crested and marbled newts live and breed in vegetation-rich ponds or similar aquatic habitats for two to six months and usually spend the rest of the year in shady, protection-rich land habitats close to their breeding sites. Males court females with a ritualised display, ending in the deposition of a spermatophore that is picked up by the female. After fertilisation, a female lays 200–400 eggs, folding them individually into leaves of water plants. Larvae develop over two to four months before metamorphosing into land-dwelling juveniles.

Historically, most European newts were included in the genus, but taxonomists have split off the alpine newts (Ichthyosaura), the small-bodied newts (Lissotriton) and the banded newts (Ommatotriton) as separate genera. The closest relatives of Triturus are the European brook newts (Calotriton). Two species of marbled newts and seven species of crested newts are accepted, of which the Anatolian crested newt was only described in 2016. Their ranges are largely contiguous but where they do overlap, hybridisation may take place.

Although not immediately threatened, crested and marbled newts suffer from population declines caused mainly by habitat loss and fragmentation. Both their aquatic breeding sites and the cover-rich, natural landscapes upon which they depend during their terrestrial phase are affected. All species are legally protected in Europe, and some of their habitats have been designated as special reserves.

Taxonomy

The genus name Triturus was introduced in 1815 by the polymath Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, with the northern crested newt (Triturus cristatus) as type species.[2] That species was originally described as Triton cristatus by Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768, but Linnaeus had already used the name Triton for a genus of sea snails ten years before, making a new genus name for the newts necessary.[3][5]

Triturus included most European newt species until the end of the 20th century, but was substantially revised after it was shown to be polyphyletic.[3] Three separate genera now accommodate former members of the genus: the small-bodied newts (Lissotriton), the banded newts (Ommatotriton), and the alpine newt (Ichthyosaura). The monophyly of the genus Triturus in the strict sense is supported by molecular data[1] and synapomorphies such as a genetic defect causing 50% embryo mortality (see below, Egg deposition and development).

As of 2020, the genus contains seven species of crested newts and two species of marbled newts.[3][6] Both groups were long considered as single species, Triturus cristatus and T. marmoratus, respectively. Substantial genetic differences between subspecies were, however, noted and eventually led to their recognition as full species, with the crested newts often collectively referred to as "T. cristatus superspecies".[3] The Balkan and the Anatolian crested newt, the most recent species formally described (2013 and 2016, respectively), were only recognised through genetic data; together with the Southern crested newt, they form a cryptic species complex with no morphological differences known.[7][4]

Description

Common characteristics

Triturus is a genus of rather large-bodied newts. They typically have a total length of between 10 and 16 cm (3.9 and 6.3 in), with some crested newts of up to 20 cm (8 in) described. Size depends on sex and the environment: females are slightly larger and have a proportionally longer tail than males in most species, and the Italian crested newt seems to be larger in colder parts of its range.[8]: 12–15 [9]: 142–147

Crested newts are dark brown, with black spots on the sides, and white stippling in some species. Their belly is yellow to orange with black blotches, forming a pattern characteristic for individuals. Females and juveniles of some species have a yellow line running down their back and tail. During breeding phase, crested newts change in appearance, most markedly the males. These develop a skin seam running along their back and tail; this crest is the namesake feature of the crested newts and can be up to 1.5 cm high and very jagged in the northern crested newt. Another feature of males at breeding time is a silvery-white band along the sides of the tail.[8]: 12–15 [9]: 142–147

Marbled newts owe their name to their green–black, marbled colour pattern. In females, an orange-red line runs down back and tail. The crest of male marbled newts is smaller and fleshier than that of the crested newts and not indented, but marbled newt males also have a whitish tail band at breeding time.[9]: 142–147

Species identification

Apart from the obvious colour differences between crested and marbled newts, species in the genus also have different body forms. They range from stocky with sturdy limbs in the Anatolian, Balkan and the southern crested newt as well as the marbled newts, to very slender with short legs in the Danube crested newt.[7] These types were first noted by herpetologist Willy Wolterstorff, who used the ratio of forelimb length to distance between fore- and hindlimbs to distinguish subspecies of the crested newt (now full species); this index however sometimes leads to misidentifications.[8]: 10 The number of rib-bearing vertebrae in the skeleton was shown to be a better species indicator. It ranges from 12 in the marbled newts to 16–17 in the Danube crested newt and is usually observed through radiography on dead or sedated specimens.[10][11]

The two marbled newts are readily distinguished by size and colouration.[12] In contrast, separating crested newt species based on appearance is not straightforward, but most can be determined by a combination of body form, coloration, and male crest shape.[8]: 10–15 The Anatolian, Balkan, and southern crested newt however are cryptic, morphologically indistinguishable species.[4] Triturus newts occupy distinct geographical regions (see Distribution), but hybrid forms occur at range borders between some species and have intermediate characteristics (see Hybridisation and introgression).

Based on the books of Griffiths (1996)[9] and Jehle et al. (2011),[8] with additions from articles on recently recognised species.[4][7][12] NRBV = number of rib-bearing vertebrae, values from Wielstra & Arntzen (2011).[10] Triturus anatolicus, T. ivanbureschi and T. karelinii are cryptic species and have only been separated through genetic analysis.[7][4]

| Image | Species | Length and build | Back and sides | Underside | Male crest | NRBV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. anatolicus (Anatolian crested newt), T. ivanbureschi (Balkan or Buresh's crested newt), T. karelinii (southern or Persian crested newt) | 10–13 cm, exceptionally up to 18 cm; stocky | Dark brown with black spots, heavy white stippling, white markings on cheeks | Orange with numerous black spots, also on throat; tail underside bright orange | Fairly indented | 13 |

| T. carnifex (Italian or alpine crested newt) | Up to 17 cm (females); medium build, legs large | Dark brown with black spots, no or little white stippling; females and juveniles often with yellow or greenish dorsal line | Yellow or orange with some large, round, grey to black, blurred spots | High | 14 |

| T. cristatus (northern or great crested newt) | 15–16 cm; moderately slender, legs medium-sized | Dark brown with black spots and white stippling | Yellow or orange, black blotches with sharp edges | Very high (up to 1.5 cm) and jagged | 15 |

| T. dobrogicus (Danube crested newt) | 13–15 cm; slender, legs short | Dark brown with black spots and white stippling | Orange to red with small to medium-sized, well defined black blotches | Very high and jagged, starting between eyes and nostrils | 16–17 |

| T. macedonicus (Macedonian crested newt) | 14–16 cm; medium build, legs large | Dark brown with black spots, dense white stippling on sides | Yellow with black blotches smaller than in T. carnifex, not blurred | High | 14 |

| T. marmoratus (marbled newt) | 15–16 cm; stocky | Dark-spotted, reticulate or marbled on green background; sometimes fine white stippling on flanks; females often with orange-red line from back to tail | Blackish with fine white spots, but no yellow markings | Fleshy, with vertical black bars | 12 |

| T. pygmaeus (southern or pygmy marbled newt) | 10–12 cm; stocky | Dark-spotted, reticulate or marbled on green background; females often with orange-red line from back to tail | Yellow-cream with large black and smaller white spots | Fleshy, with vertical black bars | 12 |

Lifecycle and behaviour

Like other newts, Triturus species develop in the water as larvae, and return to it each year for breeding. Adults spend one half to three quarters of the year on land, depending on the species, and thus depend on both suitable aquatic breeding sites and terrestrial habitats. After larval development in the first year, juveniles pass another year or two before reaching maturity; in the north and at higher elevations, this can take longer. The larval and juvenile stages are the riskiest for the newts, while survival is higher in adults. Once the risky stages passed, adult newts usually attain an age of seven to nine years, although individuals of the northern crested newts have reached 17 years in the wild.[8]: 98–99

Aquatic phase

The aquatic habitats preferred by the newts are stagnant, mid- to large-sized, unshaded water bodies with abundant underwater vegetation but without fish, which prey on larvae. Typical examples are larger ponds, which need not be of natural origin; indeed, most ponds inhabited by the northern crested newt in the UK are human-made.[8]: 48 Examples of other suitable secondary habitats are ditches, channels, gravel pit lakes, garden ponds, or (in the Italian crested newt) rice paddies. The Danube crested newt is more adapted to flowing water and often breeds in river margins, oxbow lakes or flooded marshland, where it frequently co-occurs with fish. Other newts that can be found in syntopy with Triturus species include the smooth, the palmate, the Carpathian, and the alpine newt.[8]: 44–48 [9]: 142–147 [13]

Adult newts begin moving to their breeding sites in spring when temperatures stay above 4–5 °C (39–41 °F). This usually occurs in March for most species, but can be much earlier in the southern parts of the distribution range. Southern marbled newts mainly breed from January to early March and may already enter ponds in autumn.[14] The time adults spend in water differs among species and correlates with body shape: while it is only about three months in the marbled newts, it is six months in the Danube crested newt, whose slender body is best adapted to swimming.[8]: 44 Triturus newts in their aquatic phase are mostly nocturnal and, compared to the smaller newts of Lissotriton and Ichthyosaura, usually prefer the deeper parts of a water body, where they hide under vegetation. As with other newts, they occasionally have to move to the surface to breathe air. The aquatic phase serves not only for reproduction, but also offers the animals more abundant prey, and immature crested newts frequently return to the water in spring even if they do not breed.[8]: 52–58 [9]: 142–147

Terrestrial phase

During their terrestrial phase, crested and marbled newts depend on a landscape that offers cover, invertebrate prey and humidity. The precise requirements of most species are still poorly known, as the newts are much more difficult to detect and observe on land. Deciduous woodlands or groves are in general preferred, but conifer woods are also accepted, especially in the far northern and southern ranges. The southern marbled newt is typically found in Mediterranean oak forests.[15] In the absence of forests, other cover-rich habitats, as for example hedgerows, scrub, swampy meadows, or quarries, can be inhabited. Within such habitats, the newts use hiding places such as logs, bark, planks, stone walls, or small mammal burrows; several individuals may occupy such refuges at the same time. Since the newts in general stay very close to their aquatic breeding sites, the quality of the surrounding terrestrial habitat largely determines whether an otherwise suitable water body will be colonised.[8]: 47–48, 76 [13][16]

Juveniles often disperse to new breeding sites, while the adults in general move back to the same breeding sites each year. The newts do not migrate very far: they may cover around 100 metres (110 yd) in one night and rarely disperse much farther than one kilometre (0.62 mi). For orientation, the newts likely use a combination of cues including odour and the calls of other amphibians, and orientation by the night sky has been demonstrated in the marbled newt.[17] Activity is highest on wet nights; the newts usually stay hidden during daytime. There is often an increase in activity in late summer and autumn, when the newts likely move closer to their breeding sites. Over most of their range, they hibernate in winter, using mainly subterranean hiding places, where many individuals will often congregate. In their southern range, they may instead sometimes aestivate during the dry months of summer.[8]: 73–78 [13]

Diet and predators

Like other newts, Triturus species are carnivorous and feed mainly on invertebrates. During the land phase, prey include earthworms and other annelids, different insects, woodlice, and snails and slugs. During the breeding season, they prey on various aquatic invertebrates, and also tadpoles of other amphibians such as the common frog or common toad, and smaller newts.[8]: 58–59 Larvae, depending on their size, eat small invertebrates and tadpoles, and also smaller larvae of their own species.[13]

The larvae are themselves eaten by various animals such as carnivorous invertebrates and water birds, and are especially vulnerable to predatory fish.[13] Adults generally avoid predators through their hidden lifestyle but are sometimes eaten by herons and other birds, snakes such as the grass snake, and mammals such as shrews, badgers and hedgehogs.[8]: 78 They secrete the poison tetrodotoxin from their skin, albeit much less than for example the North American Pacific newts (Taricha).[18] The bright yellow or orange underside of crested newts is a warning coloration which can be presented in case of perceived danger. In such a posture, the newts typically roll up and secrete a milky substance.[8]: 79

Reproduction

Courtship

A complex courting ritual performed underwater characterises the crested and marbled newts. Males are territorial and use leks, or courtship arenas, small patches of clear ground where they display and attract females. When they encounter other males, they use the same postures as described below for courting to impress their counterpart. Occasionally, they even bite each other; marbled newts seem more aggressive than crested newts. Males also frequently disturb the courting of other males and try to guide the female away from their rival. Pheromones are used to attract females, and once a male has found one he will pursue her and position himself in front of her. After this first orientation phase, courtship proceeds with display and spermatophore transfer.[8]: 80–89 [9]: 58–63

Courtship display serves to emphasise the male's body and crest size and to waft pheromones towards the female. A position characteristic for the large Triturus species is the "cat buckle", where the male's body is kinked and often rests only on the forelegs ("hand stand"). He will also lean towards the female ("lean-in"), rock his body, and flap his tail towards her, sometimes lashing it violently ("whiplash"). If the female shows interest, the ritual enters the third phase, where the male creeps away from her, his tail quivering. When the female touches his tail with her snout, he deposits a packet of sperm (a spermatophore) on the ground. The ritual ends with the male guiding the female over the spermatophore, which she then takes up with her cloaca. In the southern marbled newt, courtship is somewhat different from the larger species in that it does not seem to involve male "cat buckles" and "whiplashes", but instead slower tail fanning and undulating of the tail tip (presumably to mimic a prey animal and lure the female).[8]: 80–89 [9]: 58–63 [14]

Egg deposition and development

Females usually engage with several males over a breeding season. The eggs are fertilised internally in the oviduct. The female deposits them individually on leaves of aquatic plants, such as water cress or floating sweetgrass, usually close to the surface, and, using her hindlegs, folds the leaf around the eggs as protection from predators and radiation. In the absence of suitable plants, the eggs may also be deposited on leaf litter, stones, or even plastic bags. In the northern crested newt, a female takes around five minutes for the deposition of one egg. Crested newt females usually lay around 200 eggs per season, while the marbled newt (T. marmoratus) can lay up to 400. Triturus embryos are usually light-coloured, 1.8–2 mm in diameter with a 6 mm jelly capsule, which distinguishes them from eggs of other co-existing newt species that are smaller and darker-coloured. A genetic particularity in the genus causes 50% of the embryos to die: their development is arrested when they do not possess two different variants of chromosome 1 (i.e., when they are homozygous for that chromosome).[8]: 61–62 [9]: 62–63, 147 [19][6]

Larvae hatch after two to five weeks, depending largely on temperature. In the first days after hatching, they live on their remaining embryonic yolk supply and are not able to swim, but attach to plants or the egg capsule with two balancers, adhesive organs on their head. After this period, they begin to ingest small invertebrates, and actively forage about ten days after hatching. As in all salamanders and newts, forelimbs—already present as stumps at hatching—develop first, followed later by the back legs. Unlike smaller newts, Triturus larvae are mostly nektonic, swimming freely in the water column. Just before the transition to land, the larvae resorb their external gills; they can at this stage reach a size of 7 centimetres (2.8 in) in the larger species. Metamorphosis takes place two to four months after hatching, but the duration of all stages of larval development varies with temperature. Survival of larvae from hatching to metamorphosis has been estimated at a mean of roughly 4% for the northern crested newt, which is comparable to other newts. In unfavourable conditions, larvae may delay their development and overwinter in water, although this seems to be less common than in the small-bodied newts. Paedomophic adults, retaining their gills and staying aquatic, have occasionally been observed in several crested newt species.[8]: 64–71 [9]: 73–74, 144–147

Distribution

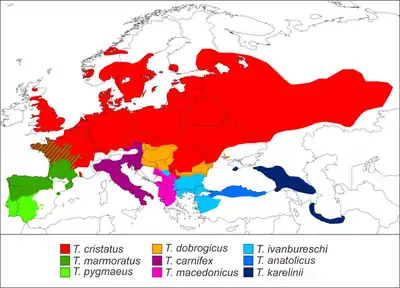

Crested and marbled newts are found in Eurasia, from Great Britain and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to West Siberia and the southern Caspian Sea region in the east, and reach north to central Fennoscandia. Overall, the species have contiguous, parapatric ranges; only the northern crested newt and the marbled newt occur sympatrically in western France, and the southern crested newt has a disjunct, allopatric distribution in Crimea, the Caucasus, and south of the Caspian Sea.[7]

The northern crested newt is the most widespread species, while the others are confined to smaller regions, e.g. the southwestern Iberian Peninsula in the southern marbled newt,[15] and the Danube basin and some of its tributaries in the Danube crested newt.[20] The Italian crested newt (T. carnifex) has been introduced outside its native range in some European countries and the Azores.[21] In the northern Balkans, four species of crested newt occur in close vicinity, and may sometimes even co-exist.[8]: 11

Triturus species usually live at low elevation; the Danube crested newt for example is confined to lowlands up to 300 m (980 ft) above sea level.[20] However, they do occur at higher altitudes towards the south of their range: the Italian crested newt is found up to 1,800 m (5,900 ft) in the Apennine Mountains,[22] the southern crested newt up to 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in the southern Caucasus,[22] and the marbled newt up to around 2,100 m (6,900 ft) in central Spain.[23]

Evolution

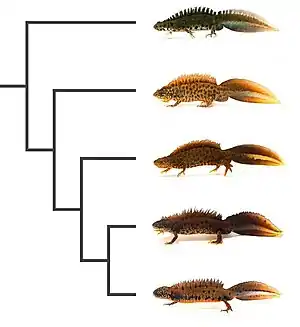

The closest relatives of the crested and marbled newts are the European brook newts (Calotriton).[1][25] Phylogenomic analyses resolved the relationships within the genus Triturus: The crested and the marbled newts are sister groups, and within the crested newts, the Balkan–Asian group with T. anatolicus, T. karelinii and T. ivanbureschi is sister to the remaining species. The northern (T. cristatus) and the Danube crested newt (T. dobrogicus), as well as the Italian (T. carnifex) and the Macedonian crested newt (T. macedonicus), respectively, are sister species.[10][24] These relationships suggest evolution from a stocky build and mainly terrestrial lifestyle, as today found in the marbled newts, to a slender body and a more aquatic lifestyle, as in the Danube crested newt.[24]

A 24-million-year-old fossil belonging to Triturus, perhaps a marbled newt, shows that the genus already existed at that time.[1] A molecular clock study based on this and other fossils places the divergence between Triturus from Calotriton at around 39 mya in the Eocene, with an uncertainty range of 47 to 34 mya.[1] Based on this estimation, authors have investigated diversification within the genus and related it to paleogeography: The crested and marbled newts split between 30 and 24 mya, and the two species of marbled newts have been separated for 4.7–6.8 million years.[10]

The crested newts are believed to have originated in the Balkans[26] and radiated in a brief time interval between 11.5 and 8 mya: First, the Balkan–Asian group (the Anatolian, Balkan and southern crested newt) branched off from the other crested newts, probably in a vicariance event caused by the separation of the Balkan and Anatolian land masses. The origin of current-day species is not fully understood so far, but one hypothesis suggests that ecological differences, notably in the adaptation to an aquatic lifestyle, may have evolved between populations and led to parapatric speciation.[10][27] Alternatively, the complex geological history of the Balkan peninsula may have further separated populations there, with subsequent allopatric speciation and the spread of species into their current ranges.[26]

Glacial refugia and recolonisation

At the onset of the Quaternary glacial cycles, around 2.6 mya, the extant Triturus species had already emerged.[10] They were thus affected by the cycles of expansion and retreat of cold, inhospitable regions, which shaped their distribution. A study using environmental niche modelling and phylogeography showed that during the Last Glacial Maximum, around 21,000 years ago, crested and marbled newts likely survived in warmer refugia mainly in southern Europe. From there, they recolonised the northern parts after glacial retreat. The study also showed that species range boundaries shifted, with some species replacing others during recolonisation, for example the southern marbled newt which expanded northwards and replaced the marbled newt. Today's most widespread species, the northern crested newt, was likely confined to a small refugial region in the Carpathians during the last glaciation, and from there expanded its range north-, east- and westwards when the climate rewarmed.[27][28]

Hybridisation and introgression

The northern crested newt and the marbled newt are the only species in the genus with a considerable range overlap (in western France). In that area, they have patchy, mosaic-like distributions and in general prefer different habitats.[23][29] When they do occur in the same breeding ponds, they can form hybrids, which have intermediate characteristics. Individuals resulting from the cross of a crested newt male with a marbled newt female had mistakenly been described as distinct species Triton blasii de l'Isle 1862, and the reverse hybrids as Triton trouessarti Peracca 1886. The first type is much rarer due to increased mortality of the larvae and consists only of males, while in the second, males have lower survival rates than females. Overall, viability is reduced in these hybrids and they rarely backcross with their parent species. Hybrids made up 3–7% of the adult populations in different studies.[30]

Other Triturus species only meet at narrow zones on their range borders. Hybridisation does occur in several of these contact zones, as shown by genetic data and intermediate forms, but is rare, supporting overall reproductive isolation. Backcrossing and introgression do however occur as shown by mitochondrial DNA analysis.[31] In a case study in the Netherlands, genes of the introduced Italian crested newt were found to introgress into the gene pool of the native northern crested newt.[32] The two marbled newt species can be found in proximity in a narrow area in central Portugal and Spain, but they usually breed in separate ponds, and individuals in that area could be clearly identified as one of the two species.[12][33] Nevertheless, there is introgression, occurring in both directions at some parts of the contact zone, and only in the direction of the southern marbled newt where that species had historically replaced the marbled newt[34] (see also above, Glacial refugia and recolonisation).

Threats and conservation

Most of the crested and marbled newts are listed as species of "least concern" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, but population declines have been registered in all assessed species.[21][35][36][37] The Danube crested newt and the southern marbled newt are considered "near threatened" because populations have declined significantly.[15][20] Populations have been affected more heavily in some countries and species are listed in some national red lists.[13] The Anatolian, Balkan and the Macedonian crested newt, recognised only recently, have not yet been evaluated separately for conservation status.[38]

Reasons for decline

The major threat for crested and marbled newts is habitat loss. This concerns especially breeding sites, which are lost through the upscaling and intensification of agriculture, drainage, urban sprawl, and artificial flooding regimes (affecting in particular the Danube crested newt). Especially in the southern ranges, exploitation of groundwater and decreasing spring rain, possibly caused by global warming, threaten breeding ponds. Aquatic habitats are also degraded through pollution with agricultural pesticides and fertiliser. Introduction of crayfish and predatory fish threatens larval development; the Chinese sleeper has been a major concern in Eastern Europe. Exotic plants can also degrade habitats: the swamp stonecrop replaces natural vegetation and overshadows waterbodies in the United Kingdom, and its hard leaves are unsuitable for egg-laying to crested newts.[9]: 106–110 [13]

Land habitats, equally important for newt populations, are lost through the replacement of natural forests by plantations or clear-cutting (especially in the northern range), and the conversion of structure-rich landscapes into uniform farmland. Their limited dispersal makes the newts especially vulnerable to fragmentation, i.e. the loss of connections for exchange between suitable habitats.[9]: 106–110 [13] High concentrations of road salt have been found to be lethal to crested newts.[39]

Other threats include illegal collection for pet trade, which concerns mainly the southern crested newt, and the northern crested newt in its eastern range.[13][36] The possibility of hybridisation, especially in the crested newts, means that native species can be genetically polluted through the introduction of close species, as it is the case with the Italian crested newt introduced in the range of the northern crested newt.[32] Warmer and wetter winters due to global warming may increase newt mortality by disturbing their hibernation and forcing them to expend more energy.[8]: 110 Finally, the genus is potentially susceptible to the highly pathogenic fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, introduced to Europe from Asia.[40]

Conservation measures

The crested newts are listed in Berne Convention Appendix II as "strictly protected", and the marbled newts in Appendix III as "protected".[41] They are also included in Annex II (species requiring designation of special areas of conservation; crested newts) and IV (species in need of strict protection; all species) of the EU habitats and species directive.[42] As required by these frameworks, their capture, disturbance, killing or trade, as well as the destruction of their habitats, are prohibited in most European countries.[41][42] The EU habitats directive is also the basis for the Natura 2000 protected areas, several of which have been designated for the crested newts.[13]

Habitat protection and management is seen as the most important element for the conservation of Triturus newts. This includes preservation of natural water bodies, reduction of fertiliser and pesticide use, control or eradication of introduced predatory fish, and the connection of habitats through sufficiently wide corridors of uncultivated land. A network of aquatic habitats in proximity is important to sustain populations, and the creation of new breeding ponds is in general very effective as they are rapidly colonised when other habitats are nearby. In some cases, entire populations have been moved when threatened by development projects, but such translocations need to be carefully planned to be successful.[8]: 118–133 [9]: 113–120 [13] Strict protection of the northern crested newt in the United Kingdom has created conflicts with local development projects; at the same time, the charismatic crested newts are seen as flagship species, whose conservation also benefits a range of other amphibians.[13]

References

- Steinfartz, S.; Vicario, S.; Arntzen, J.W.; Caccone, Adalgisa (2007). "A Bayesian approach on molecules and behavior: reconsidering phylogenetic and evolutionary patterns of the Salamandridae with emphasis on Triturus newts". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 308B (2): 139–162. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21119. ISSN 1552-5007. PMID 16969762.

- Rafinesque C.S. (1815). Analyse de la nature ou Tableau de l'univers et des corps organisés (in French). Palermo: Jean Barravecchia. p. 78.

- Frost, D.R. (2020). "Triturus Rafinesque, 1815. Amphibian Species of the World 6.0, an Online Reference". New York: American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- Wielstra, B.; Arntzen, J.W. (2016). "Description of a new species of crested newt, previously subsumed in Triturus ivanbureschi (Amphibia: Caudata: Salamandridae)". Zootaxa. 4109 (1): 73–80. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4109.1.6. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 27394852.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae: Salvius. p. 658.

- Wielstra, B. (2019). "Triturus newts". Current Biology. 29 (4): R110–R111. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.12.049. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 30779894.

- Wielstra, B.; Litvinchuk, S.N.; Naumov, B.; Tzankov, N.; Arntzen, J.W. (2013). "A revised taxonomy of crested newts in the Triturus karelinii group (Amphibia: Caudata: Salamandridae), with the description of a new species". Zootaxa. 3682 (3): 441–53. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.3682.3.5. hdl:1887/3281008. ISSN 1175-5334. PMID 25243299.

- Jehle, R.; Thiesmeier, B.; Foster, J. (2011). The crested newt. A dwindling pond dweller. Bielefeld, Germany: Laurenti Verlag. ISBN 978-3-933066-44-2.

- Griffiths, R.A. (1996). Newts and salamanders of Europe. London: Poyser. ISBN 0-85661-100-X.

- Wielstra, B.; Arntzen, J.W. (2011). "Unraveling the rapid radiation of crested newts (Triturus cristatus superspecies) using complete mitogenomic sequences". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (1): 162. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-162. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 3224112. PMID 21672214.

- Arntzen, J.W.; Wallis, G.P. (2007). "Geographic variation and taxonomy of crested newts (Triturus cristatus superspecies): morphological and mitochondrial DNA data" (PDF). Contributions to Zoology. 68 (3): 181–203. doi:10.1163/18759866-06803004. ISSN 1383-4517.

- García-París, M.; Arano, B.; Herrero, P. (2001). "Molecular characterization of the contact zone between Triturus pygmaeus and T. marmoratus (Caudata: Salamandridae) in Central Spain and their taxonomic assessment" (PDF). Revista española de herpetología. 15: 115–126. ISSN 0213-6686.

- Edgar, P.; Bird, D.R. (2006). Action plan for the conservation of the crested newt Triturus cristatus species complex in Europe (PDF). Convention on the conservation of European wildlife and natural habitats Standing Committee 26th meeting. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-02.

- Hidalgo-Vila, J.; Pérez-Santigosa, N.; Díaz-Paniagua, C. (2002). "The sexual behaviour of the pygmy newt, Triturus pygmaeus" (PDF). Amphibia-Reptilia. 23 (4): 393–405. doi:10.1163/15685380260462310. hdl:10261/65829. ISSN 0173-5373.

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Triturus pygmaeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T59479A89709552. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T59479A89709552.en. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Jehle, R. (2000). "The terrestrial summer habitat of radio-tracked great crested newts (Triturus cristatus) and marbled newts (T. marmoratus)". The Herpetological Journal. 10: 137–143.

- Diego-Rasilla, J.; Luengo, R. (2002). "Celestial orientation in the marbled newt (Triturus marmoratus)" (PDF). Journal of Ethology. 20 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1007/s10164-002-0066-7. ISSN 0289-0771. S2CID 8565821.

- Wakely, J.F.; Fuhrman, G.J.; Fuhrman, F.A.; Fischer, H.G.; Mosher, H.S. (1966). "The occurrence of tetrodotoxin (tarichatoxin) in amphibia and the distribution of the toxin in the organs of newts (Taricha)". Toxicon. 3 (3): 195–203. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(66)90021-3. ISSN 0041-0101. PMID 5938783.

- Horner, H.A.; Macgregor, H.C. (1985). "Normal development in newts (Triturus) and its arrest as a consequence of an unusual chromosomal situation". Journal of Herpetology. 19 (2): 261. doi:10.2307/1564180. ISSN 0022-1511. JSTOR 1564180.

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Triturus dobrogicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T22216A89709283. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T22216A89709283.en. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Triturus carnifex". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T214696589A89706627. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T214696589A89706627.en. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- Arntzen, J.W.; Borkin, L. (2004). "Triturus superspecies cristatus (Laurenti, 1768)". In Gasc J.-P.; Cabela A.; Crnobrnja-Isailovic J.; et al. (eds.). Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles in Europe. Paris: Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. pp. 76–77. ISBN 2-85653-574-7.

- Zuiderwijk, A. (2004). "Triturus marmoratus (Latreille, 1800)". In Gasc J.-P.; Cabela A.; Crnobrnja-Isailovic J.; et al. (eds.). Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles in Europe. Paris: Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle. pp. 82–83. ISBN 2-85653-574-7.

- Wielstra, B.; McCartney-Melstad, E.; Arntzen, J.W.; Butlin, R.K.; Shaffer, H.B. (2019). "Phylogenomics of the adaptive radiation of Triturus newts supports gradual ecological niche expansion towards an incrementally aquatic lifestyle". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 133: 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.12.032. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 30630099.

- Carranza, S.; Amat, F. (2005). "Taxonomy, biogeography and evolution of Euproctus (Amphibia: Salamandridae), with the resurrection of the genus Calotriton and the description of a new endemic species from the Iberian Peninsula". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 145 (4): 555–582. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00197.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- Crnobrnja-Isailovic, J.; Kalezic, M.L.; Krstic, N.; Dzukic, G. (1997). "Evolutionary and paleogeographical effects on the distribution of the Triturus cristatus superspecies in the central Balkans". Amphibia-Reptilia. 18 (4): 321–332. doi:10.1163/156853897X00378. ISSN 0173-5373.

- Wielstra, B.; Babik, W.; Arntzen, J.W. (2015). "The crested newt Triturus cristatus recolonized temperate Eurasia from an extra-Mediterranean glacial refugium". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 114 (3): 574–587. doi:10.1111/bij.12446. ISSN 0024-4066.

- Wielstra, B.; Crnobrnja-Isailović, J.; Litvinchuk, S.N.; Reijnen, B.T.; Skidmore, A.K.; et al. (2013). "Tracing glacial refugia of Triturus newts based on mitochondrial DNA phylogeography and species distribution modeling". Frontiers in Zoology. 10 (13): 13. doi:10.1186/1742-9994-10-13. PMC 3608019. PMID 23514662.

- Schoorl, J.; Zuiderwijk, A. (1980). "Ecological isolation in Triturus cristatus and Triturus marmoratus (Amphibia: Salamandridae)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 1 (3): 235–252. doi:10.1163/156853881X00357. ISSN 0173-5373.

- Arntzen, J.W.; Jehle, R.; Bardakci, F.; Burke, T.; Wallis, G.P. (2009). "Asymmetric viability of reciprocal-cross hybrids between crested and marbled newts (Triturus cristatus and T. marmoratus" (PDF). Evolution. 63 (5): 1191–1202. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00611.x. ISSN 0014-3820. PMID 19154385. S2CID 12083435.

- Arntzen, J.W.; Wielstra, B.; Wallis, G.P. (2014). "The modality of nine Triturus newt hybrid zones assessed with nuclear, mitochondrial and morphological data". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 113 (2): 604–622. doi:10.1111/bij.12358. ISSN 0024-4066.

- Meilink, W.R.M.; Arntzen, J.W.; van Delft, J.C.W.; Wielstra, B. (2015). "Genetic pollution of a threatened native crested newt species through hybridization with an invasive congener in the Netherlands". Biological Conservation. 184: 145–153. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.01.022. ISSN 0006-3207.

- Espregueira Themudo, G.; Arntzen, J.W. (2007). "Molecular identification of marbled newts and a justification of species status for Triturus marmoratus and T. pygmaeus" (PDF). The Herpetological Journal. 17 (1): 24–30. ISSN 0268-0130.

- Espregueira Themudo, G.; Nieman, A.M.; Arntzen, J.W. (2012). "Is dispersal guided by the environment? A comparison of interspecific gene flow estimates among differentiated regions of a newt hybrid zone" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 21 (21): 5324–5335. doi:10.1111/mec.12026. PMID 23013483. S2CID 13134781.

- Arntzen, J.W.; Kuzmin, S.; Jehle, R.; Beebee, T; Tarkhnishvili, D.; et al. (2009). "Triturus cristatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T22212A9365894. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T22212A9365894.en.

- Arntzen, J.; Papenfuss, T.; Kuzmin, S.; Tarkhnishvili, D.; Ishchenko, V.; et al. (2016) [errata version of 2009 assessment]. "Triturus karelinii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009: e.T39420A86228088. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009.RLTS.T39420A10235366.en.

- IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (2022). "Triturus marmoratus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T59477A89707573. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T59477A89707573.en. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. 2014. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- Duff, J.P.; Colvile, K.; Foster, J.; Dumphreys, N. (2011). "Mass mortality of great crested newts (Triturus cristatus) on ground treated with road salt". Veterinary Record. 168 (10): 282. doi:10.1136/vr.d1521. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 21498183. S2CID 207041490.

- Martel, A.; Blooi, M.; Adriaensen, C.; et al. (2014). "Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders". Science. 346 (6209): 630–631. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..630M. doi:10.1126/science.1258268. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 5769814. PMID 25359973.

- "Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats". Bern: Council of Europe. 1979. Retrieved 2015-05-24.

- "Council directive 92/43/EEC on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora". Act No. 1992L0043 of 1 January 2007. Retrieved 2015-05-31.