Crime in London

Figures on crime in London are based primarily on two sets of statistics: the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and police recorded crime data. Greater London is generally served by three police forces; the Metropolitan Police which is responsible for policing the vast majority of the capital, the City of London Police which is responsible for The Square Mile of the City of London and the British Transport Police, which polices the national rail network and the London Underground. A fourth police force in London, the Ministry of Defence Police, do not generally become involved with policing the general public. London also has a number of small constabularies for policing parks. Within the Home Office crime statistic publications, Greater London is referred to as the London Region.

.jpg.webp)

Current trends

The Mayor's Office for Policing & Crime (MOPAC) prepares quarterly performance reports for policing and crime in the Greater London area. Q1 2021[1] showed a reduction in all crime in London with the exception of hate crimes and domestic violence. Total notifiable offences (TNO) had decreased by 17.2% when compared to the same quarter in 2019/20 (-20,465) and had decreased by 8.1% (17,148) compared to Q2 2020. These figures include COVID-19 lockdown periods.

The Office for National Statistics data between June 2016 and March 2020 showed per person crime had increased by 31% in England and by a lower margin of 18% in London since 2016.[2] These statistics only count crime recorded by police,[3] and it's estimated by that overall crime continues to decrease.[4]

The increase in crime recorded in London is not uniform across different types of offence. For example, while homicides increased over the period by 23% in London compared to 8% across England, violence against the person in general increased by 2% in London compared to 7% across England.[2] Over the same period, sexual offences recorded by police in London fell by 2% while in England they remained flat; robbery increased by 16% in London, compared to 6% across England. Otherwise, the increase in London over 2019/20 was largely driven by an increase in theft offences, including burglary. Theft[5] is stealing from a person without the use or threat of force, robbery is stealing by using force or the threat of force on someone and burglary is entering a property illegally in order to steal. Theft offences account for 50% of the Metropolitan Police's recorded crimes and increased by 4% last year. Across England, they fell 5%.

Over the longer period, the trend is similar. Since 2016, the number of police recorded theft offences (without force or threat) per person has increased by 23% in London, compared to a rise of 7% in England more widely, accounting for much of the recorded increase in crime in the capital.

His Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) independently assess the effectiveness and efficiency of police forces. In 2018, they reported the Met recorded just 89.5%[6] of reported crime. Increases in recorded crime since are likely to be partly credited to improvements in the recording of reported crime across London, rather than simply an increase in crime experienced by residents and visitors.

A report that London crime had risen five times faster than the rest of the country since Sadiq Khan became Mayor in 2016 was debunked[7] by the independent fact checker Full Fact.[8] The misinformation is credited to Dan Wootton in The Sun on 1 October 2020,[7] who may have misinterpreted an article in the Evening Standard on 17 July 2020[9] claiming the "over-arching figure for the total number of offences recorded by Metropolitan Police in the last financial year rose by five per cent in 2018".

Violent crime

Offences categorised as "violent crime" by the Home Office are violence against the person,[10] including robbery and sexual offences; it sometimes includes kidnapping. It was announced in September 2018 that the city planned to emulate Scotland's public health approach, inspired by Cure Violence in Chicago, to violent crime. This saw the murder rate in Glasgow drop by more than a half between 2004 and 2017. In 2018, Sadiq Khan announced funding of £500,000 for a Violence Reduction Unit, though this has been criticised as insufficient.[11]

Homicide

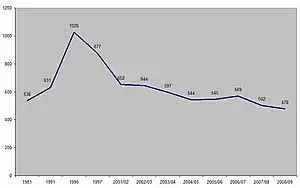

Between 1990 and 2003, the number of homicides, i.e. murder, manslaughter, etc. in London averaged 120 per year, with a low of 109 in 1996, and a high of 222 in 2003. The number then fell in each and every year between 2004 and 2014 to a new low of 83. They then rose sharply to 118 in 2015 and 110 in 2016.[n 1] In 2017, there was a further rise to 131, although this included the combined 14 victims of the Westminster Bridge (5), London Bridge (8) and Finsbury Park (1) terrorist attacks, but even with these major events was still lower than any year between 1990 and 2009.[24] As of 31 December 2018, there have been 132 homicides reported in London in 2018.[25] The year 2019 was reportedly London's bloodiest year since more than a decade, which recorded an eleven-year high of 143 people being killed.[26][27] As of 31 December 2019, the number of homicides reported reached 149, the highest in a decade.[28] 2021 broke the record set in 2008 for teen homicide.[29] This was reportedly the highest rate since World War II.[30]

Of the 126 cases looked into by the Met:[31]

- 31 of them were categorised as domestic violence offences, included 12 resulting from stabbing

- 44 of the homicides took place in a dwelling and 71 of them on the street

- Of the 126 victims, 14 were teenagers and 40 were aged between 20 and 24

- 31 of the homicides were assessed as “gang-related”

- In 14 cases the killer used a firearm, and in 71, a knife

| Year | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

| Number of homicides in London[32][33] | 184 | 184 | 175 | 160 | 169 | 167 | 139 | 190 | 159 | 146 | 171 | 190 | 189 | 221 | 194 | 165 | 174 | 163 | 154 | 129 | 124 | 118 | 104 | 107 | 94 | 119 | 110 | 131 | 137 | 149 | 123 | 127 |

| Homicide Rate (per 100,000) | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.4 | |

| London Population (thousands)[34] | 6,829 | 6,829 | 6,844 | 6,874 | 6,913 | 6,974 | 7,015 | 7,065 | 7,154 | 7,237 | 7,322 | 7,377 | 7,395 | 7,433 | 7,519 | 7,598 | 7,693 | 7,812 | 7,943 | 8,061 | 8,204 | 8,309 | 8,417 | 8,539 | 8,667 | 8,770 | 8,825 | 8,908 | 8,961 | 9,002 |

| Number of homicides in 2017 | Homicide Rate | Population (thousands) | |

| London | 118 | 1.3 | 8,825 |

| Berlin[35] | 91 | 2.6 | 3,500 |

| Madrid[35] | 39 | 1.2 | 3,200 |

| Rome (2016)[35] | 21 | 0.7 | 2,900 |

| Amsterdam[35] | 19 | 2.3 | 813 |

The distribution of homicide offences in London can vary significantly by borough.

Between 2001 and 2015 there were 2,326 offences committed in London.

| Rank | Borough | Number of homicides 2001 to 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lambeth | 154 |

| 2 | Southwark | 124 |

| 3 | Newham | 122 |

| 4 | Hackney | 114 |

| 5 | Brent | 100 |

| 6 | Haringey | 97 |

| 7 | Croydon | 87 |

| 8 | Camden | 85 |

| 9 | Ealing | 84 |

| 10 | Lewisham | 83 |

| 11 | Tower Hamlets | 83 |

| 12 | Waltham Forest | 73 |

| 13 | Greenwich | 71 |

| 14 | Islington | 70 |

| 15 | Enfield | 66 |

| 16 | Westminster | 63 |

| 17 | Wandsworth | 62 |

| 18 | Hillingdon | 61 |

| 19 | Barnet | 48 |

| 20 | Hammersmith and Fulham | 48 |

| 21 | Hounslow | 42 |

| 22 | Barking & Dagenham | 42 |

| 23 | Bromley | 38 |

| 24 | Redbridge | 38 |

| 25 | Bexley | 30 |

| 26 | Havering | 28 |

| 27 | Merton | 26 |

| 28 | Sutton | 25 |

| 29 | Harrow | 24 |

| 30 | Kensington & Chelsea | 23 |

| 31 | Kingston upon Thames | 17 |

| 32 | Richmond upon Thames | 14 |

Moped crime

A noted trend since 2014 is robberies and assaults committed by individuals riding mopeds; crime involving mopeds rose by more than 600% in London between 2014 and 2016.[36]

Assault with injury

Assault with injury, currently comprising assault occasioning actual bodily harm and grievous bodily harm by the Metropolitan Police, accounts for on average 40% of all violence against the person offences within the Metropolitan Police area and 45% of all violence against the person nationally.[37] In England and Wales, 'assault without injury' and harassment account for a further 38% of crimes recorded within the violence against the person category.

In 2008–09, there 70,962 assault with injury offences in London with a rate of 9.5 per 1,000 residents.[38] This was slightly higher than the total rate for England and Wales, which was 7.0 per 1,000 residents.[39]

| Crime rate | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABH and GBH rate per 1,000 London | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 9.4 | 11.2 | 10.4 | 9.5 | 9.5 |

| ABH and GBH rate per 1,000 England & Wales | 3.6 | 3.8 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 9.0 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 7.0 |

Following the changes introduced by the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) in 2002, the way assaults were categorised was dependent on injury, leading to a significant jump in combined ABH and GBH figures nationally in 2002–03. Prior to NCRS, minor injuries were counted as common assault, while after NCRS any assault with injury would be categorised as ABH. Looking at figures over time is of limited value as figures prior to 2002–03 are not comparable with the way certain violent crimes have been recorded since then. These changes were not reflected in the Metropolitan Police performance figures until 2004/05, when the rate almost doubled to 9.4 per 1,000 residents compared to 5.8 the previous year. In 2005–06, the rate of recorded ABH and GBH peaked both nationally and within the Metropolitan Police force area according to recorded statistics.

The British Crime Survey or BCS is a systematic victim study, currently carried out by BMRB Limited on behalf of the Home Office. The BCS seeks to measure the amount of crime in England and Wales by asking around 50,000 people aged 16 and over, living in private households, about the crimes they have experienced in the last year. The survey is comparable to the National Crime Victimization Survey conducted in the United States. The Home Office estimated that just 37% of violence with injury offences were reported to and recorded by police.

An advantage of the BCS is that it has not been affected by the changes in counting rules and the way crime is categorised because it is survey-based. This makes it possible to observe national trends in crime over time. Crime in England and Wales 2008/09,[41] shows BCS violence with injury to have peaked in 1995 and declined steadily since then. Between 1995 and 2008–09, the BCS estimates that violence with injury offences decreased 53.6% across England & Wales.

Gun and knife crime

Weapon-enabled crimes are recorded by the Metropolitan Police when a weapon is used to assist a crime, for example a gun being used as part of a robbery. Recorded gun- and knife-enabled offences in London account for about 2% of total recorded crime. The two London Boroughs with the highest rate of gun and knife crime are Southwark and Lambeth. Other London Boroughs with high gun and knife crime rates include Brent, Haringey and Hackney.[42] Gun-enabled crime figures are displayed on the Metropolitan Police website at borough level expressed as financial year to date comparisons[43] but they are seldom made available for historical comparisons. Figures are available for calendar years 2000 to 2007[44] as shown in the table below.[43][45]

| Crime rate | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gun-enabled crime | 2961 | 3250 | 4005 | 4444 | 4025 | 3744 | 3881 | 3327 | 3459 | 2525 | 3295 |

| Rate per 10,000 London | 3.9 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 4.4 |

Since 2000, there has been consistent fluctuations in the number of gun-enabled crimes recorded by the Metropolitan Police, which peaked in 2003 when there were 4,444 recorded offences. The lowest number of offences recorded was potentially in 2008, where there were just 1,980 gun-enabled crimes between December 2007 and November 2008, an unusually low figure in comparison to other years. Since then, however, gun-enabled crime has increased 67% across London with 3,309 offences being recorded in the twelve months to November 2009.

| Crime rate | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knife-enabled crime[45] | 10305 | 12985 | 12367 | 12301 | 10699 | 12345 | 12611 |

| Rate per 10,000 London | 13.7 | 17.3 | 16.5 | 16.4 | 14.3 | 16.4 | 16.8 |

Knife-enabled crime figures are available from 2003 to 2007 and more recently monthly knife crime summaries are provided on the Metropolitan Police website showing financial year to date figures.[46] Knife enabled offences increased from 2003 to 2004 and from then on saw annual reductions until 2007. It was not possible to retrieve statistics for 2008 and 2009.

The Metropolitan Police a number of operations that concentrate on knife and gun crime. They include Operation Trident and Trafalgar which deal with fatal and non-fatal shootings across London, Operation Blunt which was initially launched across 12 boroughs in 2004 to tackle knife crime and subsequently rolled out across the forces 32 boroughs in 2005 after early successes.[47] Operation Blunt was re-launched as Operation Blunt II in 2008 with the aim of tackling serious youth violence.[48] In addition to this there is the Specialist Firearms Command formerly known as SO19.

There has been an overall increase of crime rate especially knife stabbings from April 2010 (1093) to November 2018 (1208).[49] The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, said that the knife crime offenders will be tagged with tracking GPS devices for a year upon their release from the prison, which will record their movements against the location of reported crimes & revert to police with the information.[50]

Key Insights

- Knife-related crime had a yearly increase of 10% in England and Wales in 2021.

- Teenage deaths due to knife crimes were the highest in 18 years.

- Men perform most of the London stabbing offences.

- Class, social standing, and socio-economic background are the only correlated causes of violent crimes.

Robbery

Recording of robbery offences in England and Wales are sub-divided into Business Robbery (robbery of a business, e.g. a bank robbery) and Personal Robbery (taking an individual's personal belongings with force/threat).[51] Annually business robbery offences in London account for on average 10% of total robbery offences.

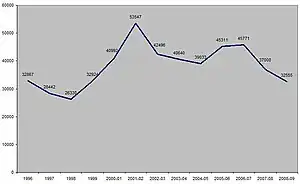

| Crime Rate | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000–01 | 2001–02 | 2002–03 | 2003–04 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London Robbery Offences[52][53][54][55] | 32867 | 28442 | 26330 | 32924 | 40992 | 53547 | 42496 | 40640 | 39033 | 45311 | 45771 | 37000 | 32555 | 33463 | 35857 |

| Rate per 1,000 London | 4.4 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

Robbery offending across London fell almost 20% between 1996 and 1998 from 32,867 to 26,330 offences. Following changes in counting rules of crimes, and the later introduction of the National Crime Recording Standard, offences of robbery rose both nationally and within London.[56] In London, offences increased by 25% in 1999, compared with 1998. There was a 25% increase between 1999 and 2000/01 and a further 30% increase between 2000/01 and 2001/02 when the robbery rate in London peaked to 7.1 offences per 1,000 population. In March 2002, the government launched the 'Street Crime Initiative' with the aim of reducing robbery in the most affected police forces, including the Metropolitan Police. Nationally, the 'Street Crime Initiative' achieved a reduction in robbery of 32% by March 2005.[57] In London during the same period, robbery reduced by 27% from 53,547 in 2001/02 to 39,033 in 2004/05. After the initiative had finished, robbery offences increased and stayed at a rate of around 6.0 per 1,000 for the next two financial years, however, there has now been a steady annual decline in robbery rates across London since 2006/07.

The increases in robbery were largely attributed to the rise in youth on youth robberies across London with particular focus around schools and transport interchanges and increased usage and ownership of items such as mobile phones, one of the most commonly stolen items. The increases that followed the end of the street crime initiative were thought somewhat to be a result of the increased mobility of young people when the introduction of oyster cards to provide under-16s free travel on London's transport network was introduced.[58]

Race and crime

City of London Police

A stop and search overview from July 2017 to June 2018 found that black people were two times more likely to be stopped than white people. When stopped, whites were more unwilling to state their ethnicity than other racial groups. The most common reason for a search was suspected drugs possession. Asians were most commonly stopped in relation to drugs (66%), and then blacks (62%). Whites were subjected to a notable lower level of drug searches (50%). However, despite this, whites had the lowest rate of NFA (no further action). For Asians, 60% of individuals were no further actioned and 28% were arrested. For blacks, roughly 61% of individuals were no further actioned and 20% were arrested. For whites, only 53% were no further actioned while the arrest rate was 27%. Overall, blacks had the lowest arrest rate and the highest no further action rate - despite being subjected to twice as many searches as whites. When stopped, whites were the most likely to be found in breach of drug laws, having the lowest corresponding no further action rate.[59]

Metropolitan Police

In the year to March 2020, there were 563,837 stop and searches in England and Wales (these figures include the British Transport Police). Almost half of these searches were carried out by the Metropolitan Police. As of the 2011 Census, 40.2% of Londoners identified as BAME. London has the highest stop and search rates for most ethnic minority groups.[60][61][62] Amid growing concerns that police were disproportionately targeting black Londoners, the then-Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Cressida Dick, acknowledged that the force “is not free of discrimination, racism or bias".[63] Deputy Assistant Commissioner, Bas Javid, admitted that the Metropolitan Police has a problem with racism.[64] In 2023, a 363-page report written by Baroness Casey found the organisation to be institutionally racist, misogynistic, homophobic and corrupt.[65]

Street crimes include muggings, assault with intent to rob, and snatching property. Black males accounted for 29 percent of the male victims of gun crime and 24 percent of the male victims of knife crime. Similar statistics were recorded for females. On knife crime, 45 percent of suspected female perpetrators were black; for gun crime, 58 percent; and for robberies, 52 percent.[66] A study by the Home Office published in 2003 found that 70 per cent of mugging victims on commuter railways around London identified their muggers as black.[67] The study also reported that 87 per cent of victims in Lambeth, South London, told the police that their attackers were black.[68]Operation Trident was set up in March 1998 by the Metropolitan Police to investigate gun crime in London's black community after black-on-black shootings in Lambeth and Brent.[69] According to the government-elected body London Assembly, in an article posted in 2022 regarding a motion held by the authority, black Londoners make up 45% of London’s knife murder victims and 61% of knife murder[70] perpetrators.

Regarding drugs, white people are the most likely to be found in possession when stopped and searched.[71] Whites were also more likely to be found in possession of weapons when searched. Overall, criminal offences were more likely to be detected among whites and Asians after stop and search.[72]

Regarding Human trafficking and modern slavery, Eastern Europeans and Chinese gangs are the main perpetrators.[73]

Between April 2005 and January 2006, figures from the Metropolitan Police Service showed that black people accounted for 46 percent of car-crime arrests generated by automatic number plate recognition cameras.[74]

In June 2010, The Sunday Telegraph, through a Freedom of Information Act request, obtained statistics on accusations (as opposed to actual convictions) of crime broken down by race from the Metropolitan Police Service.[n 2] The figures showed that the majority of males who were accused of violent crimes in 2009–10 were black. Of the recorded 18,091 such accusations against males, 54 percent accused of street crimes were black; for robbery, 59 percent; and for gun crimes, 67 percent. However, black people tend to have a slightly lower conviction ratio (the percentage of defendants convicted out of all those prosecuted) so arrests from accusations and suspicions often fail to result in corresponding convictions. In the same The Sunday Telegraph report, Simon Woolley commented: “Although the charge rates for some criminal acts amongst black men are high, black people are more than twice as likely to have their cases dismissed, suggesting unfairness in the system".

In 2017, The Independent reported on statistics from HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMICFRS), for the year 2016-17. The Metropolitan Police and City of London Police were among the 43 police forces considered. The report found that white people more likely to be carrying drugs when stopped and searched - despite being searched up to eight times less than black people.[71]

In 2018, Sky News initiated a freedom of information request to every police force in the country. The statistics showed that black people were over-represented as victims of homicide and in homicide convictions in London, with 48% of murder suspects being black, compared to 13% of the population.[75] However, black people tend to have slightly lower conviction rates, so arrests from accusations often fail to result in a corresponding conviction. Gov.uk reported that in 2017 the conviction rate for black suspects was 78.7, compared to the Asian average of 80.3 in the same year and the white conviction rate of 85.3. [76]

In 2019, The Guardian reported on statistics obtained from the Mayor's Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) for the year 2018. The figures revealed that despite whites being subjected to significantly lower levels of stop and search than blacks, crime was more likely to be detected amongst white Londoners, when they were stop and searched. Whites were more likely to be in possession of weapons and drugs, more likely to be arrested after a search and more likely to be found guilty than black Londoners - despite black Londoners being targeted by police more often. The Guardian quoted figures showing for white Londoners, 30.5% of searches resulted in further action, for Asians 27.8%, and for black Londoners 26.7%. Dr Krisztián Pósch, from the London School of Economics commented: "The data shows that police are not just stopping black people more disproportionately, but are less likely to detect crime when they do compared to when they stop white people”.[72]

According to the National Crime Agency (NCA), human trafficking in the UK is a rapidly growing issue with criminal, labour and sexual as the most common forms of exploitation.[77] The Joint Committee On Human Rights state human traffickers tend to be "split between people from the Far East, the Chinese gangs, and Eastern European gangs".[73] As of 2004, vice squad officers estimated Albanian operations in London's Soho were worth more than £15 million a year.[78] In 2020, a report by ITV News stated that 70% of London's brothels are controlled by Albanians.[79] According to a 2020 Home Office report, the UK cocaine market is now largely dominated by Albanian Organised Crime Groups.[80] Tony Saggers (former head of drugs threat and intelligence at the National Crime Agency), stated the sale of cocaine in most major UK cities, including London, is now largely controlled by Albanian crime groups.[81] London is the primary "hub" for Albanian organised crime.[82] Albanians have overtaken Poles as the largest group of foreign prisoners in UK jails.[83][84]

Bicycle thefts

In 2014, the number of bicycles reported stolen to the Metropolitan Police and City of London Police forces came to 17,809.[85] However, the true number of bicycle thefts may be much larger as many victims do not report it to the police. According to the British Crime Survey and Transport for London, only one in four victims of bicycle thefts actually report the crime.[86]

Metropolitan force comparisons

Below are crime rate comparisons for London and the metropolitan districts of England in 2007/08 financial year.[87][88]

| Police force | Main city | Homicides | Firearms offences | Violence against the person |

Sexual offences | Robbery | Burglary (residential) | Theft of and from motor vehicles |

| Greater London | London | 2.0 | 45.3 | 23.2 | 1.2 | 4.9 | 8.0 | 16.0 |

| Greater Manchester | Manchester | 1.9 | 44.6 | 19.3 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 8.3 | 16.7 |

| West Midlands | Birmingham | 1.6 | 37.5 | 20.5 | 1.2 | 2.9 | 6.9 | 13.1 |

| Merseyside | Liverpool | 2.3 | 29.5 | 15.4 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 6.2 | 10.7 |

| South Yorkshire | Sheffield | 2.1 | 15.0 | 18.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 6.6 | 15.4 |

| West Yorkshire | Leeds | 2.1 | 15.1 | 17.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 8.5 | 13.2 |

| Northumbria Police (Tyne and Wear) | Newcastle | 2.1 | 5.6 | 13.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 8.1 |

| England | London | 1.4 | 18.9 | 17.5 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 11.1 |

Notable crime

- Jack the Ripper terrorised London in the 19th century.

- In the 80s and 90s, the IRA set off a number of bombs in London.

- The racist murder of Stephen Lawrence in 1993.

- In July 2005, terrorists set off four bombs on three London Underground trains and a double-decker bus, killing 52 and injuring over 700, in the country's first Islamist suicide attack.

- Murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby. On 22 May 2013, a British Army soldier, Fusilier Lee Rigby of the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, was attacked and killed by Michael Adebolajo and Michael Adebowale near the Royal Artillery Barracks in Woolwich, southeast London.

- Wayne Couzens, a Metropolitan Police constable, kidnapped Sarah Everard, a 33-year-old woman and later murdered her in 2021.

Footnotes

- [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

- The figures relate to those 'proceeded against', including those prosecuted in court, whether convicted or acquitted; those issued with a caution, warning or penalty notice; those the Crown Prosecution Service decided not to charge; and those whose crimes were 'taken into consideration' after a further offence.[66]

References

- "Mayor's Office for Policing & Crime Quarterly Performance Update Report Quarter 3 2020/21" (PDF). MOPAC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Crime in England and Wales: Police Force Area data tables - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Crime figures: Do the police know how much there really is?". BBC News. 8 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Crime in England and Wales - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 11 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "What is the difference between theft, robbery and burglary? – Sentencing". Archived from the original on 4 April 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Constabulary, © Her Majesty's Inspectorate of; Fire. "The Metropolitan Police Service: Crime Data Integrity inspection 2018". HMICFRS. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Crime in London has risen less than the rest of England since 2016". Full Fact. 5 October 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Who we are". Full Fact. Archived from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- France, Anthony (17 July 2020). "London crime up five times more than national average". www.standard.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Violence against the Person" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "London knife crime: Can Chicago's model cure the violence?". BBC. 21 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 September 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- "HOSB Issue 04/00 22 February 2000 International comparisons of criminal justice statistics 1998" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "Performance Information 2007 Annual \(Calendar Year\) Crime Stats" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Crime Mapping Data Tables". Maps.met.police.uk. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2000/01". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2001/02". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2002/03". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2003/04". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2004/05". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2005/06". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2006/07". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2007/08". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "MPS Borough Level Crime Figures 2008/09". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Crime in England and Wales: Police Force Area Data Tables – Office for National Statistics". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2018.

- "London killings: All the victims of 2018". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "2019 ends with 143 London killings amid murder probe into fight death". London Evening Standard. 2 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Kane, Hannah (2 January 2020). "Murder investigation launched as man found critically injured in Surbiton park". getwestlondon. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Number of homicides in London climbs to 10-year high". The Guardian. 31 December 2019. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "London teen homicides: How killings broke 2008 record". BBC News. 31 December 2021. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- "Two stabbings takes London teen murder toll to highest level since Second World War". www.londonworld.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- Hill, Dave (20 January 2021). "The number of homicides in London fell in 2020. What explains why these sad statistics change?". OnLondon. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- "Crime data dashboard | The Met". www.met.police.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Number of homicides in London climbs to 10-year high". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 January 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- "Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Beswick, Emma (6 April 2018). "How bad is London's murder rate compared to other EU capitals?". euronews. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "Moped Crime". Archived from the original on 26 October 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Crime in England and Wales 2008/09" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "MPS Monthly Crime Totals". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Home Office: Crime in England and Wales 2008/09, p.30" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Home Office: Crime in England and Wales 2008/09, p/30" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Home Office: Crime in England and Wales 2008/09, p. 28" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "London gun crime figures 'worryingly high' – Channel 4 News". Channel 4. 30 March 2011. Archived from the original on 24 June 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Interactive Crime Figures accessed 10.01.10". Met.police.uk. Archived from the original on 3 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Crime Summary 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011.

- "Crime Summary 2007, p.2" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011.

- "MPS Monthly Knife Crime Summary, November 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Tackling Knife Crime: Operation Blunt". Archived from the original on 22 October 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- Metropolitan Police. "More than 500 knives seized in Blunt 2". Cms.met.police.uk. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Hate crime or special crime dashboard | The Met". www.met.police.uk. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Desk, Mirror News (14 February 2019). "GPS Devices to Track Knife Crime Offenders in London". The Mirror Herald. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Home Office Counting Rules: Robbery" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Metropolitan Police Crime Data Tables (2000–01 to 2008–09 data)". Maps.met.police.uk. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Notifiable Offences, England & Wales 1996" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Notifiable Offences, England & Wales 1997" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Recorded Crime in England & Wales 1998–99" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "BBC Street Crime Surges 18.01.00". BBC News. 18 January 2000. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Home Office: Tackling Robbery, practical lessons from the street crime initiative". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Government Office for London: Personal Robbery Project 2007" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Stop Search Figures Overview" (PDF). Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- "Stop and search". www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk. 22 February 2021. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- "Regional ethnic diversity". www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk. 1 August 2018. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- "Stop and search data and the effect of geographical differences". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 11 April 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Vaughan, henry (13 November 2020). "Met Commissioner admits force 'not free of discrimination, racism or bias'". belfasttelegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 July 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- White, Nadine (15 February 2022). "'Racism is a problem in Metropolitan Police,' senior officer admits". The Independent. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2022.

- Dodd, Vikram (21 March 2023). "Met police found to be institutionally racist, misogynistic and homophobic". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Alderson, Andrew. "Violent inner-city crime, the figures, and a question of race" Archived 21 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph. 26 June 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2010.

- "70% of muggers are black in robbery hotspots". The Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019.

- "70% of muggers are black in robbery hotspots". The Times. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2021.

- "Q&A: Operation Trident" Archived 1 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- "Calls for a commission on knife crime in the black community | London City Hall". www.london.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2023.

- Dearden, Lizzie (12 December 2017). "White people more likely to be carrying drugs when stopped and searched". The Independent. Archived from the original on 21 April 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- Dodd, Vikram (26 January 2019). "Met police 'disproportionately' use stop and search powers on black people". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- "The scale and nature of human trafficking in the UK". 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Gadher, Dipesh. "Cameras set racial poser on car crime" Archived 16 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. The Times. 14 May 2006. Retrieved 27 September 2010.

- "Black murder victims and suspects: London v UK". Archived from the original on 25 July 2018.

- "Prosecutions and convictions". Gov.uk. Archived from the original on 20 January 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "NCA assessment". 2020. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- McGrory, Daniel (17 July 2004). "Albanian gangs control violent vice networks". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Watson, Lucy (17 September 2020). "London's sex slave industry: How ITV News uncovered the story". ITV News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "Review of drugs: summary (accessible version)". GOV.UK. 17 September 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Townsend, Mark (13 January 2019). "Kings of cocaine: how the Albanian mafia seized control of the UK drugs trade". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 May 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "National Strategic Assessment 2017". 2017. Archived from the original on 9 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- "Government strikes deal to remove more Albanian prisoners". GOV.UK. 26 July 2021. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Davis, Matthew (23 January 2022). "Shock rise in Albanian criminals in UK prisons - PressReader". Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 7 April 2022 – via PressReader.

- "The State of Bike Thefts in London, UK in 2014". Litelok.com. 10 June 2015. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Transport for London – Cycle Security Plan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Home Office Homicide, Firearms Offences and Intimate Violence 2007/08" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- "Home Office: Crime in England & Wales 2007/08" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

External links

- Additional information

- Government Office for London Data & Analytical Tools

- Give Life Domestic Violence Project

- Home Office Statistical Publications Archive

- Knife City – Carrying a knife. Its not a game

- Metropolitan Police Crime Mapping Site Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Metropolitan Police Publication Scheme Archived 8 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- National Policing Improvement Agency Local Crime Mapping

- London City Hall - Making London Safer for Young People

- Maps