Cromemco Dazzler

The Cromemco Dazzler was a graphics card for S-100 bus computers introduced in a Popular Electronics cover story in 1976.[1] It was the first color graphics card available for microcomputers.[2] The Dazzler was the first of a succession of increasingly capable graphics products from Cromemco which, by 1984, were in use at 80% of all television stations in the U.S. for the display of weather, news, and sports graphics.[3]

History

The Dazzler came about in a roundabout fashion after Les Solomon, Technical Editor for Popular Electronics magazine, demonstrated the original Altair 8800 to Roger Melen of Stanford University. After seeing it, Melen purchased Altair #2 for his friend Harry Garland to work with. The two built a number of add-ons for the machine, collaborating with Terry Walker on the design of the first digital camera called the Cyclops and then moving on to the Dazzler.[1][2] The Dazzler was first shown at the Homebrew Computer Club on November 12, 1975.[4]

Like many early microcomputer projects of the era, the Dazzler was originally announced as a self-built kit in Popular Electronics.[5] In order to "kick start" construction, they offered kits including a circuit board and the required parts, which the user would then assemble on their own. This led to sales of completely assembled Dazzler systems, which became the only way to purchase the product some time after. Sales were so fruitful that Melen and Garland formed Cromemco to sell the Dazzler and their other Altair add-ons, selecting a name based on Crothers Memorial Hall, their residence while attending Stanford.

When Federico Faggin's new company - Zilog - introduced the Z80, Cromemco branched out into their own line of Z80-based S-100 compatible computers almost immediately. Over time these became the company's primary products. Combinations of their rackmount machines and the Dazzler formed the basis of ColorGraphics Weather Systems (CWS) product line into the late 1980s, and when CWS was purchased by Dynatech in 1987, Dynatech also purchased Cromemco to supply them.[3]

Dazzler software

.jpg.webp)

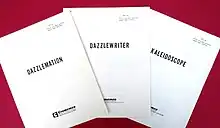

The original advertisement for the Dazzler offered three different software programs for sale (provided on punched paper tape.)[6] These were Conway's Game of Life, Dazzlewriter (an alphanumeric display) and a colorful pattern-generating program, Kaleidoscope.

The cover of the June 1976 issue of Byte magazine shows a Dazzler image from Conway's Game of Life, and credits Ed Hall as author of the Game of Life software for the Dazzler. Byte also credits Steve Dompier with authoring the animation tool "Dazzlemation" and the first animation made with Dazzlemation called "Magenta Martini". George Tate (who later co-founded Ashton-Tate) is credited with a Tic-Tac-Toe game for the Dazzler, and Li-Chen Wang is credited as the author of "Kaleidoscope".[7] Ed Hall's color realization of Conway's Game of Life led to a revival of interest in the game.[8]

Stan Veit, owner of the Computer Mart of New York, described the reaction when he displayed the changing patterns of Kaleidoscope on a color television in his store window at the corner of 5th Avenue and 32nd Street in New York City in early 1976. “People driving by began to stop and look – they had never seen anything like it before. In a short time the Dazzler had caused a traffic jam on 5th Avenue!” The police had to contact the building landlord and make him disconnect the television.[9]

Over time, Cromemco introduced additional software for the Dazzler, at first on paper tape and later floppy disk, including Spacewar! in October 1976.[10][11] Cromemco customers also developed software for a wide range of graphics applications, from monitoring the manufacturing processes at a coffee factory in Columbia[12] to displaying real-time images of heart blood flow, generated through cardiac radionuclide imaging, in Scotland.[13]

Dazzler hardware

.jpg.webp)

The Dazzler used over 70 MOS and TTL ICs, which required two cards to hold all the chips,[14] "Board 1" held the analog circuits, while "Board 2" held the bus interface and digital logic. The two cards were connected together with a 16-conductor ribbon cable. Although the analog card did not talk on the bus, it would normally be plugged into the bus for power connections and physical support within the chassis. The manual[15] also described a way to "piggyback" the two cards with a separate power cable to save a slot. Output from the analog card was composite color, and an RF modulator was available for direct connection to a color TV.

The Dazzler lacked its own frame buffer, accessing the host machine's main memory using a custom DMA controller that provided 1 Mbit/s throughput.[16] The card read data from the computer at speeds that demanded the use of SRAM memory, as opposed to lower cost DRAMs. Control signals and setup was sent and received using the S-100 bus's input/output "ports", normally mapped to 0E and 0F. 0E contained an 8-bit address pointing to the base of the frame buffer in main memory, while 0F was a bit-mapped control register with various setup information.

The Dazzler supported four graphics modes in total, selected by setting or clearing bits in the control register (0F) that controlled two orthogonal selections. The first selected the size of the frame buffer, either 512 bytes or 2 kB. The other selected normal or "X4" mode, the former using 4-bit nybbles packed 2 to a byte in the frame buffer to produce an 8-color image, or the latter which was a higher resolution monochrome mode using 1-bits per pixel, 8 to a byte. Selecting the mode indirectly selected the resolution. In normal mode with a 512 byte buffer there would be 512 bytes × 2 pixels per byte = 1,024 pixels, arranged as a 32 by 32 pixel image. A 2 kB buffer produced a 64 by 64 pixel image, while the highest resolution used a 2 kB buffer in X4 mode to produce a 128 by 128 pixel image.[17] In normal mode the color was selected from a fixed 8-color palette with an additional bit selecting intensity (4-bit RGBI), while in X4 mode the foreground color was selected by setting three bits in the control register to turn on red, green or blue (or combinations) while a separate bit controlled the intensity.

Super Dazzler

In 1979, Cromemco replaced the original Dazzler with the Super Dazzler.[18] The Super Dazzler Interface (SDI) had 756 x 484 pixel resolution with the ability to display up to 4096 colors (12-bit RGB), a capability that had previously only been available in much more expensive systems.[19][20] Dedicated two-port memory cards were used for image storage for higher performance. While the original Dazzler had a composite video output signal, the new SDI used separate RGB component video outputs for higher resolution. The SDI also had the ability to be synchronized to other video equipment. Cromemco systems with the SDI board became the systems of choice for television broadcast applications,[21] and were widely deployed by the United States Air Force as Mission Support Systems.[22]

See also

- Video of Super Dazzler display in 1987 on YouTube

- MicroAngelo, a higher-resolution system for S-100 computers

- Matrox, Matrox's first graphics product was a video card for S-100 machines, the ALT-256

- VDM-1, a text-only display that was the first interface for S-100 machines

References

- Les Solomon, "Solomon's Memory" Archived 2012-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, in Digital Deli, Workman Publications, 1984, ISBN 0-89480-591-6

- Harry Garland, "Ten years and counting", Creative Computing, Volume 10, Number 11 (November 1984), pg. 104

- Melton, Louise (November 1984). "Video Processing". Computer & Electronics. 22 (11): 96.

Some 80% of all the television stations in the country use Colorgraphics's LiveLine systems to generate weather, news and sports graphics. The basic system is built around Cromemco microcomputers.

- Reiling, Robert (November 30, 1975). "Club Meeting November 12, 1975". Homebrew Computer Club Newsletter. Mountain View CA: Homebrew Computer Club. 1 (9): 1.

Equipment demonstrations at this meeting of 1) TV Dazzler manufactured by CROMEMCO, One First Street, Los Altos, CA 94022, 2) Video Display Module manufactured by Processor Technology Company, 2465 Fourth Street, Berkeley, CA 94710, and 3) IMSAI 8080 System manufactured by IMS Associated Inc., 1922 Republic Avenue, San Leandro, CA 94577.

- Walker, Terry; Melen, Roger; Garland, Harry; Hall, Ed (1976). "Build the TV Dazzler". Popular Electronics. Vol. 9, no. 2. pp. 31–40.

- "Now your color TV can be your computer display terminal". Byte. No. 8. April 1976. p. 7.

- Helmers, Carl (June 1976). "About the Cover". Byte. No. 10. pp. 6–7. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- McIntosh, Harold (2008). "Introduction" (PDF). Journal of Cellular Automata. 13: 181–186. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

With the advent of microcomputers and Cromemco's graphics board, Life became a favorite display program for video monitors and led to a revival of interest in the game

- Veit, Stan (March 1990). "Cromemco - Innovation and Reliability". Computer Shopper. 3. 10 (122): 481–487.

- Cromemco Inc., "Spacewar", 1976

- "Cromemco Dazzler Games 1977". Cromemco. 1977. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

- "Cromemco in South America". I/O News. 5 (2): 14. January–February 1986. ISSN 0274-9998.

- "Micro-based Heart Diagnostics". Systems International: 40–42. August 1984. ISSN 0309-1171.

- Manual, pg. 3

- Cromemco Dazzler Manual (PDF). Cromemco. 1977.

- Manual, pg. 4

- Manual, pg. 6

- Fox, Tom (December 1979). "Cromemco's Superdazzler". Interface Age. 4 (12): 74–77.

- ""Super Dazzler" Color Video Board". The Intelligent Machines Journal. No. 15. October 3, 1979.

- Fox, Tom (December 1979). "Cromemco's Super Dazzler". Interface Age. 4 (12): 74–77.

The SDI color graphics subsystem presents a breakthrough in capabilities that have previously been available only in far more expensive computers.

- "Cromemco Computer Graphics 1987". wn.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

- Kuhman, Robert. "The Cro's Nest RCP/M-RBBS". www.kuhmann.com. Retrieved 2012-02-10.

External links

- Saga of a System - David Ahl's story of how he got his Altair 8800/Dazzler system built, includes some sample images

- Cromemco Dazzler - image of the original design and its instruction manual

- Build the TV Dazzler - original Popular Electronics article