Cuban macaw

The Cuban macaw or Cuban red macaw (Ara tricolor) is an extinct species of macaw native to the main island of Cuba and the nearby Isla de la Juventud. It became extinct in the late 19th century. Its relationship with other macaws in its genus was long uncertain, but it was thought to have been closely related to the scarlet macaw, which has some similarities in appearance. It may also have been closely related, or identical, to the hypothetical Jamaican red macaw. A 2018 DNA study found that it was the sister species of two red and two green species of extant macaws.

| Cuban macaw | |

|---|---|

| |

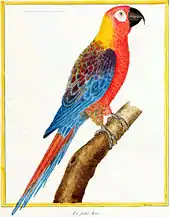

| Watercolour painting by Jacques Barraband, ca. 1800 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Psittaciformes |

| Family: | Psittacidae |

| Genus: | Ara |

| Species: | †A. tricolor |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ara tricolor (Bechstein, 1811) | |

| |

| Former distribution in Cuba, including Isla de la Juventud[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

At about 45–50 centimetres (18–20 in) long, the Cuban macaw was one of the smallest macaws. It had a red, orange, yellow, and white head, and a red, orange, green, brown, and blue body. Little is known of its behaviour, but it is reported to have nested in hollow trees, lived in pairs or families, and fed on seeds and fruits. The species' original distribution on Cuba is unknown, but it may have been restricted to the central and western parts of the island. It was mainly reported from the vast Zapata Swamp, where it inhabited open terrain with scattered trees.

The Cuban macaw was traded and hunted by Native Americans, and by Europeans after their arrival in the 15th century. Many individuals were brought to Europe as cagebirds, and 19 museum skins exist today. No modern skeletons are known, but a few subfossil remains have been found on Cuba. It had become rare by the mid-19th century due to pressure from hunting, trade, and habitat destruction. Hurricanes may also have contributed to its demise. The last reliable accounts of the species are from the 1850s on Cuba and 1864 on Isla de la Juventud, but it may have persisted until 1885.

Taxonomy

Early explorers of Cuba, such as Christopher Columbus and Diego Álvarez Chanca, mentioned macaws there in 15th- and 16th-century writings. Cuban macaws were described and illustrated in several early accounts about the island.[3] In 1811, the German naturalist Johann Matthäus Bechstein scientifically named the species Psittacus tricolor.[4] Bechstein's description was based on the bird's entry in the French naturalist François Le Vaillant's 1801 book Histoire Naturelle des Perroquets.[5][6] Le Vaillant's account was itself partially based on the late 18th century work Planches Enuminées by the French naturalists Comte de Buffon and Edme-Louis Daubenton, as well as a specimen in Paris; as it is unknown which specimen this was, the species has no holotype. The French illustrator Jacques Barraband's original watercolour painting, which was the basis of the plate in Le Vaillant's book, differs from the final illustration in showing bright red lesser wing covert feathers ("shoulder" area), but the significance of this is unclear.[7]

Today, 19 skins of the Cuban macaw exist in 15 collections worldwide (two each in Natural History Museum at Tring, Muséum national d'histoire naturelle in Paris, the Swedish Museum of Natural History, and the Smithsonian Museum), but many are of unclear provenance. Several were provided by the Cuban naturalist Juan Gundlach, who collected some of the last individuals that regularly fed near the Zapata Swamp in 1849–50. Some of the preserved specimens are known to have lived in captivity in zoos (such as Jardin des Plantes de Paris, Berlin Zoo, and Amsterdam Zoo) or as cagebirds. The single specimen at World Museum, National Museums Liverpool died in Edward Smith-Stanley, 13th Earl of Derby's aviaries at Knowsley Hall in 1846. Several more skins are known to have existed, but have been lost.[3] There are no records of its eggs.[8]

No modern skeletal remains of this macaw are known, but three subfossil specimens have been discovered: half a carpometacarpus from a possibly Pleistocene spring deposit in Ciego Montero, identified by extrapolating from the size of Cuban macaw skins and bones of extant macaws (reported in 1928), a rostrum from a Quaternary cave deposit in Caimito (reported in 1984), and a worn skull from Sagua La Grande, which was deposited in a waterfilled sinkhole possibly during the Quaternary and associated with various extinct birds and ground sloths (reported in 2008).[9][10]

Related species

As many as 13 now-extinct species of macaw have variously been suggested to have lived on the Caribbean islands, but many of these were based on old descriptions or drawings and only represent hypothetical species. Only three endemic Caribbean macaw species are known from physical remains: the Cuban macaw, the Saint Croix macaw (Ara autochthones), which is known only from subfossils, and the Lesser Antillean macaw (Ara guadeloupensis), which is known from subfossils and reports.[11][12] Macaws are known to have been transported between the Caribbean islands and from mainland South America to the Caribbean both in historic times by Europeans and natives, and in prehistoric times by Paleoamericans. Historical records of macaws on these islands, therefore, may not have represented distinct, endemic species; it is also possible that they were escaped or feral foreign macaws that had been transported to the islands.[11] All the endemic Caribbean macaws were likely driven to extinction by humans in historic and prehistoric times.[10] The identity of these macaws is likely to be further resolved only through fossil finds and examination of contemporary reports and artwork.[3]

The Jamaican red macaw (Ara gossei) was named by the British zoologist Walter Rothschild in 1905 on the basis of a description of a specimen shot in 1765. It was described as being similar to the Cuban macaw, mainly differing in having a yellow forehead. Some researchers believe the specimen described may have been a feral Cuban macaw.[3] A stylised 1765 painting of a macaw by the British Lieutenant L. J. Robins, published in a volume called The Natural History of Jamaica, matches the Cuban macaw, and may show a specimen that had been imported there; however, it has also been claimed that the painting shows the Jamaican red macaw.[11][13] Rothschild's 1907 book Extinct Birds included a depiction of a specimen in the Liverpool Museum which was presented as a Cuban macaw. In a 1908 review of the book published in The Auk, the American ornithologist Charles Wallace Richmond claimed that the picture looked sufficiently dissimilar from known Cuban macaws that the specimen may actually be of one of the largely unknown species of macaw, such as a species from Haiti.[14] This suggestion has not been accepted.[3]

The name Ara tricolor haitius was coined for a supposed subspecies from Hispaniola by the German ornithologist Dieter Hoppe in 1983, but is now considered to have been based on erroneous records.[15] In 1985, the American ornithologist David Wetherbee suggested that extant specimens had been collected from both Cuba and Hispaniola, and that the two populations represented distinct species, differing in details of their colouration. Whetherbee stated the name Ara tricolor instead applied to the supposed Hispaniolan species, as he believed Cuba had no bird collectors prior to 1822, and that the illustration and description published by Le Vaillant were based on a specimen collected during a 1798 expedition to Hispaniola. As the Cuban species was thereby in need of a new specific name, Wetherbee coined Ara cubensis for it. He also suggested that the Jamaican red macaw was based on a "tapiré"; a specimen whose colouration was altered through a Native American technique whereby developing feathers can be changed to red and yellow by painting them with body fluids of the dyeing dart frog (Dendrobates tinctorius).[16] The idea that the name Ara tricolor applied to a Hispaniolan species had gained acceptance by 1989, but in 1995, the British ornithologist Michael Walters pointed out that birds had indeed been described from Cuba prior to 1822, that the supposed differences in colouration were of no importance, and that the basis of Wetherbee's argument was therefore invalid. There is no clear evidence for a species of macaw on Hispaniola.[7][3]

Evolution

Since detailed descriptions of extinct macaws exist only for the species on Cuba, it is impossible to determine their interrelationships.[3] It has been suggested that the closest mainland relative of the Cuban macaw is the scarlet macaw (Ara macao), due to the similar distribution of red and blue in their plumage, and the presence of a white patch around the eyes, naked except for lines of small red feathers. Furthermore, the range of the scarlet macaw extends to the margins of the Caribbean Sea.[10] The two also share a species of feather mite, which supports their relationship.[3] The American ornithologist James Greenway suggested in 1967 that the scarlet macaw and the Cuban macaw formed a superspecies with the other extinct species thought to have inhabited Jamaica, Hispaniola and Guadeloupe.[17]

A 2018 DNA study by the Swedish biologist Ulf S. Johansson and colleagues analysed the mitochondrial genome of two Cuban macaw specimens in the Swedish Museum of Natural History (sampled from their toe-pads). Though it was expected the Cuban species would form a clade with the likewise predominantly red scarlet macaw and the red-and-green macaw (Ara chloropterus), they instead found it to be basal to (and sister species of) those two large red macaws, as well as to the two large green macaws, the military macaw (Ara militaris) and the great green macaw (Ara ambiguus). The cladogram below follows the 2018 study:[18]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cuban macaw was smaller than the related extant species, and one of the smallest Ara species, which suggests smaller size may have been the ancestral state of the group, though it may also have become smaller after becoming established in the Antilles. Johansson and colleagues estimated that the Cuban macaw had diverged from its mainland relatives around 4 million years ago, during the early Pliocene. Since this is after the land bridge that is thought to have connected the Greater Antilles with South America ceased to exist, the ancestors of the Cuban macaw must have dispersed to the Antilles over open water. Therefore, the Cuban macaw was not a recent offshoot of the scarlet macaw, having a long independent history on Cuba. Johansson and colleagues therefore noted that though many of the extinct species of Caribbean macaws that had been described in the past are probably dubious, there would have been ample time for a radiation of macaws there, based on how long the Cuban species had been separated from the mainland species.[18] A 2020 genetic study of the scarlet macaw by the American ecologist Kari L. Schmidt and colleagues resulted in a similar cladogram to that of Johansson and colleagues .[19]

Description

The Cuban macaw had a red forehead fading to orange and then to yellow at the nape of the neck. It had white unfeathered areas around the eyes, and yellow irises. The face, chin, chest, abdomen and thighs were orange. The upper back was brownish red with feathers scalloped with green. The rump, undertail feathers, and lower back were blue. The wing feathers were brown, red and purplish blue. The upper surface of the tail was dark red fading to blue at the tip, and the under surface of the tail was brownish red.[8] The beak has variously been described as dark, all-black, and greyish black. The legs were brown.[3][8][15] The sexes were identical in external appearance, as with other macaws.[17] The Cuban macaw was physically distinct from the scarlet macaw in its lack of a yellow shoulder patch, its all-black beak, and its smaller size.[10]

About 50 centimetres (20 in) long, the Cuban macaw was a third smaller than its largest relatives. The wing was 27.5–29 centimetres (10.8–11.4 in) long, the tail was 21.5–29 centimetres (8.5–11.4 in), the culmen 42–46 millimetres (1.7–1.8 in), and the tarsus 27–30 millimetres (1.1–1.2 in). The subfossil cranium shows that the length between the naso-frontal hinge and the occipital condyle was 47.0 millimetres (1.85 in), the width across the naso-frontal hinge was about 25.0 millimetres (0.98 in), and the width of the postorbital processes was about 40 millimetres (1.6 in). Details of the skull were similar to other Ara species.[8][9]

The American zoologist Austin Hobart Clark reported that juvenile Cuban macaws were green, though he did not provide any source for this claim. It is unclear whether green birds spotted on the island were in fact juvenile Cuban macaws or if they were instead feral military macaws.[3][20]

Behaviour and ecology

Little is known about the behaviour of the Cuban macaw and its extinct Caribbean relatives. Gundlach reported that it vocalised loudly like its Central American relatives and that it lived in pairs or families. Its speech imitation abilities were reportedly inferior to those of other parrots. Nothing is known about its breeding habits or its eggs, but one reported nest was a hollow in a palm.[3]

The skull roof of the subfossil cranium was flattened, indicating the Cuban macaw fed on hard seeds, especially from palms. This is consistent with the habits of their large relatives on mainland South America and distinct from those of smaller, mainly frugivorous relatives. In 1876, Gundlach wrote that the Cuban macaw ate fruits, seeds of the royal palm (Roystonea regia) and the chinaberry tree (Melia azedarach), as well as other seeds and shoots. Cuba has many species of palms, and those found in swamps were probably most important to the Cuban macaw.[9] The pulp surrounding the seeds of the chinaberry tree were probably the part consumed by the Cuban macaw.[3]

In 2005, a new species of chewing louse, Psittacobrosus bechsteini, was described based on a dead specimen discovered on a museum skin of the Cuban macaw.[21] It is thought to have been unique to this species, and is therefore an example of coextinction.[15] The feather mite species Genoprotolichus eurycnemis and Distigmesikya extincta have also been reported from Cuban macaw skins, the latter new to science.[3]

Distribution and habitat

The range of the Cuban macaw's distribution at the time of European settlement on the main island of Cuba is unclear, but the species was reportedly becoming rare by the mid-19th century. It may have been restricted to the central and western part of Cuba. Most accounts from the 19th century are based on Gundlach's reports from the immense Zapata Swamp, where the species was somewhat common near the northern edge. By the 1870s, it was becoming rarer and had retreated to the interior.[3] The subfossil skull from Sagua La Grande is the northernmost and easternmost record of the Cuban macaw. One subfossil rostrum was found in a cave. Caves are usually not visited by macaws, but the surrounding region is possibly a former swamp.[9] The Cuban macaw had also inhabited Isla de la Juventud (previously called Isla de Pinos/the Isle of Pines) off Cuba, but the American ornithologists Outram Bangs and Walter R. Zappey reported that the last pair was shot near La Vega in 1864.[22] Early writers also claimed it lived on Haiti and Jamaica, but this is no longer accepted.[3]

The habitat of the Cuban macaw was open savanna terrain with scattered trees, typical of the Zapata Swamp area. Cuba was originally widely covered in forest, much of which has since been converted to cropland and pastures. Lomas de Rompe, where the macaw was also reported, had rainforest-like gallery forest.[3]

Extinction

Hunting has been proposed as a factor in the extinction of the Cuban macaw. Parrots were hunted, kept as pets, and traded by Native Americans in the Caribbean before the arrival of Europeans. The Cuban macaw was reportedly "stupid" and slow to escape, and therefore was easily caught. It was killed for food; the Italian traveler Gemelli Careri found the meat tasty, but Gundlach considered it tough.[3] Archaeological evidence suggests the Cuban macaw was hunted in Havana in the 16th–18th centuries.[9] It may also have been persecuted as a crop pest, though it did not live near dwellings.[3]

In addition to being kept as pets locally, many Cuban macaws (perhaps thousands of specimens) were traded and sent to Europe. This trade has also been suggested as a contributing cause for extinction. Judging by the number of preserved specimens that originated as captives, the species was probably not uncommon in European zoos and other collections. It was popular as a cagebird, despite its reputation for damaging items with its beak. Furthermore, collectors caught young birds by observing adults and felling the trees in which they nested, although sometimes nestlings were accidentally killed. This practice reduced population numbers and selectively destroyed the species' breeding habitat. This means of collection continues today with the Cuban parakeet (Psittacara euops) and the Cuban amazon (Amazona leucocephala).[3]

A hurricane in 1844 is said to have wiped out the population of Cuban macaws from Pinar del Río. Subsequent hurricanes in 1846 and 1856 further destroyed their habitat in western Cuba and scattered the remaining population. In addition, a tropical storm hit the Zapata Swamp in 1851. With a healthy macaw population, such events could have been beneficial by creating suitable habitat. However, given the species' precarious position, it may have resulted in fragmented habitat and caused them to seek food in areas where they were more vulnerable to hunting.[3]

The extinction date of the Cuban macaw is uncertain. Gundlach's sightings in the Zapata Swamp in the 1850s and Zappey's second-hand report of a pair on Isla de la Juventud in 1864 are the last reliable accounts.[3] In 1886, Gundlach reported that he believed birds persisted in southern Cuba, which led Greenway to suggest that the species survived until 1885.[17] Parrots are often among the first species to be exterminated from a given locality, especially islands.[3][23]

According to the British writer Errol Fuller, aviculturalists are rumoured to have bred birds similar in appearance to the Cuban macaw. These birds, however, are reportedly larger in size than the Cuban macaw, having been bred from larger macaw species.[8]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Ara tricolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22724513A94870119. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22724513A94870119.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Ara tricolor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- Wiley, J. W.; Kirwan, G. M. (2013). "The extinct macaws of the West Indies, with special reference to Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 133 (2): 125–156.

- Bechstein, J. H. (1811). Johann Lathams Allgemeine Übersicht der Vögel (in German). Vol. 4. Weigel und Schneider. p. 64. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.138319. PDF version

- Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds. London: Hutchinson & Co. p. 51.

- Le Vaillant, F. O.; Barraband, Jacques; Bouquet (1801). Histoire naturelle des perroquets. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.60852.

- Walters, M. (1995). "On the status of Ara tricolor Bechstein". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 115: 168–170. ISSN 0007-1595.

- Fuller, E. (2000). Extinct Birds. Oxford University Press. pp. 233–236. ISBN 978-0-670-81787-0.

- Olson, S. L.; Suárez, W. (2008). "A fossil cranium of the Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor (Aves: Psittacidae) from Villa Clara Province, Cuba". Caribbean Journal of Science. 3. 44 (3): 287–290. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i3.a3. S2CID 87386694.

- Williams, M. I.; Steadman, D. W. (2001). "The historic and prehistoric distribution of parrots (Psittacidae) in the West Indies" (PDF). In Woods, C. A.; Sergile, F. E. (eds.). Biogeography of the West Indies: Patterns and Perspectives (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 175–189. ISBN 978-0-8493-2001-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-07.

- Olson, S. L.; Maíz López, E. J. (2008). "New evidence of Ara autochthones from an archaeological site in Puerto Rico: a valid species of West Indian macaw of unknown geographical origin (Aves: Psittacidae)" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 44 (2): 215–222. doi:10.18475/cjos.v44i2.a9. S2CID 54593515.

- Gala, M.; A. Lenoble (2015). "Evidence of the former existence of an endemic macaw in Guadeloupe, Lesser Antilles". Journal of Ornithology. 156 (4): 1061–1066. doi:10.1007/s10336-015-1221-6. S2CID 18597644.

- Turvey, S. T. (2010). "A new historical record of macaws on Jamaica". Archives of Natural History. 37 (2): 348–351. doi:10.3366/anh.2010.0016.

- Richmond, C. W. (1908). "Recent literature: Rothschild's 'Extinct Birds'". The Auk. 25 (2): 238–240. doi:10.2307/4070727. JSTOR 4070727.

- Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. A & C Black. pp. 182–183, 400. ISBN 978-1-4081-5725-1.

- Wetherbee, D. K. (1985). "The extinct Cuban and Hispaniolan macaws (Ara, Psittacidae), and description of a new species, Ara cubensis" (PDF). Caribbean Journal of Science. 21 (16): 169–175.

- Greenway, J. C. (1967). Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World. American Committee for International Wild Life Protection. pp. 314–320. ISBN 978-0-486-21869-4.

- Johansson, Ulf S.; Ericson, Per G. P.; Blom, Mozes P. K.; Irestedt, Martin (2018). "The phylogenetic position of the extinct Cuban Macaw Ara tricolor based on complete mitochondrial genome sequences". Ibis. 160 (3): 666–672. doi:10.1111/ibi.12591. ISSN 0019-1019.

- Schmidt, Kari L.; Aardema, Matthew L.; Amato, George (2020). "Genetic analysis reveals strong phylogeographical divergences within the Scarlet Macaw Ara macao". Ibis. 162 (3): 735–748. doi:10.1111/ibi.12760. S2CID 196687248.

- Clark, A. H. (1905). "The Greater Antillean Macaws". The Auk. 22 (4): 345–348. doi:10.2307/4069997. JSTOR 4069997.

- Mey, E. (2005). "Psittacobrosus bechsteini: ein neuer ausgestorbener Federling (Insecta, Phthiraptera, Amblycera) vom Dreifarbenara Ara tricolor (Psittaciiformes), nebst einer annotierten Übersicht über fossile und rezent ausgestorbene Tierläuse" (PDF). Anzeiger des Vereins Thüringer Ornithologen (in German). 5: 201–217. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-27. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- Bangs, O.; Zappey, W. R. (1905). "Birds of the Isle of Pines". The American Naturalist. 39 (460): 179–215. doi:10.1086/278509. JSTOR 2455378. S2CID 85056158.

- Clark, A. H. (1905). "The Lesser Antillean Macaws". The Auk. 22 (3): 266–273. doi:10.2307/4070159. JSTOR 4070159.