Cunizza da Romano

Cunizza da Romano (c. 1198–1279) was an Italian noblewoman and a member of the da Romano dynasty, one of the most prominent families in northeastern Italy, Cunizza's marriages and liaisons, most notably with troubadour Sordello da Goito, are widely documented. Cunizza also appears as a character in a number of works of literature, such as Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.

Biography

Early life

Cunizza da Romano was born around 1198 in the Marca Trivigiana, a region in northeastern Italy between Venice and the Alps. She was the third and youngest daughter of Ezzelino II da Romano, a Ghibelline nobleman. Cunizza, along with her two brothers Alberico da Romano and Ezzelino III da Romano, were conceived with Ezzelino's third wife, Adelaide degli Alberti di Mangona, a noblewoman of Tuscan origin.[1]

Medieval marriage and historical context

Cunizza, Alberico, and Ezzelino III were born into an era of medieval Italy that had organized a system for the distribution of wealth among family members, united by blood or marriage. A nobleman’s sons would each receive a fraterna, or equally divided inheritance. Ezzelino III received a fraterna along with his brother, Alberico, from their father in 1223, while Cunizza received 3,000 lire to be used as dowry. At this time, women were only allotted a portion of the dowry after their husband’s passing, and there is no evidence of whether Cunizza reacquired her dowry funds after her last husband died. Upon Ezzelino III’s acquisition of his inheritance, he sought the opportunity to facilitate his own military and political influence, often by forming and severing elite marriages which were in his best interest. In 1249, Ezzelino imprisoned three brothers of the esteemed dei Dalesmanini family, who were allegedly his closest allies. The brothers had arranged for their sister to be married in secret to one of Ezzelino’s political rivals, Count Rizzardo da Sanbonifacio of Verona. To Ezzelino, this union was a declaration of war. He would continue to use marriage to its extremes as an agent for war and invasions, an approach that was unorthodox to traditional marital customs.[1]

Personal life and liaisons

Along the timeline of Cunizza’s various marriages and love affairs, many of her unions were exploited by Ezzelino III in order to further his political agenda and sow discord among his rivaling factions. Much modern scholarship on medieval marriages during this time have accounted for Ezzelino III’s apparent lack of regard for marital traditions, only seeing the unions and separations as political tools for his expansion of power.[2]

In 1222, Cunizza da Romano married her first husband, the Count Rizzardo di Sanbonifacio of Verona. At the same time, Ezzelino III married the count’s sister Zilia, a double alliance that would forge peace between the Guelphs and Ghibellines in the region and ideally quell the previous hostility between Ezzelino III and Count Rizzardo. However, tension grew due to the alliance between the Sanbonifacio and the d’Este family, one of Ezzelino II’s political rivals. Both Ezzelino and his father, Ezzelino II, believed Cunizza to be at risk to a hostage situation in Rizzardo’s home, so they sent Sordello to abduct Cunizza and return her to her father’s court. In 1226, it was Ezzelino III who became the podestà and banished Rizzardo from Verona, officially severing Cunizza’s first marriage.[1]

Cunizza had given birth to Rizzardo’s son, Leoisio, whom she left when she was abducted by Sordello. Leoisio would later inherit the title of count as well as control of the castle of Sanbonifacio, a task he failed when he was manipulated by his uncle Ezzelino III to leave the castle, only for it to be destroyed.[1]

Cunizza then began a love affair with Sordello. A troubadour from Goito, Sordello is said to have fallen in love with Cunizza, and she with him, when he first saw her at Rizzardo’s court.[3] Their liaison was cut off when Ezzelino III banished him from the da Romano house to maintain their reputation. Sordello had been born into a lower social class, and thus his romance with Cunizza could have been suggested as an infiltration among the higher-ranking courtiers.

In order to avoid being married by her brother for political alliance, Cunizza took Bonio di Treviso, a knight, as her new lover, with whom she left to live with her other brother Alberico da Romano. By 1239, Alberico had become podestà of Treviso, and his efforts to organize campaigns against Ezzelino III were supported with Cunizza’s donations and Bonio’s agreement to fight. In 1242, Bonio was killed one month after Holy Saturday, while defending Treviso from one of Ezzelino’s sieges.[4]

After devoting much of her time and money to the rally against her brother, Cunizza eventually returned to live with him after losing Bonio di Treviso and facing disgrace. Ezzelino III subsequently married her off to Naimerio da Breganze, a Vicentine nobleman, as a declaration of political allegiance. However, accounts from Battista Pagliarini report that some of the da Breganze had fled Vicenza in 1256, unwilling to live under Ezzelino III’s new control of the city.[5] Multiple versions of Naimerio’s death have circulated, including murder by Ezzelino, and death in battle at Longare.[6]

Final years

After the death of both her brothers, Cunizza went to live with her maternal family, the Alberti di Mangona, in Tuscany. Two notarial documents appear with her name signed, the first being an emancipation of select da Romano slaves on April 1, 1265.[1] Cunizza’s act to “secure the salvation of the souls"[7] of her family did not include any slaves who sided against Alberico, rather the document explicitly mentions their eventual damnation into hell.[1] The signing of this declaration occurred in the house of Cavalcante de' Cavalcanti.[2]

The second was the drafting and signing of Cunizza's will in 1279; by this time, she had accumulated a vast amount of wealth. She left an inter vivo gift to her cousin, Count Alessandro degli Alberti da Mangona, a Tuscan who later appeared in the frozen circle for the betrayers of kin in Canto XXXII of Dante’s Inferno. Cunizza also had rights to the castle at Mussa, but the castle belonged to the Trevisan government following a vast reclamation of property following Ezzelino III’s death.[1]

In literature

Cunizza in the Divine Comedy

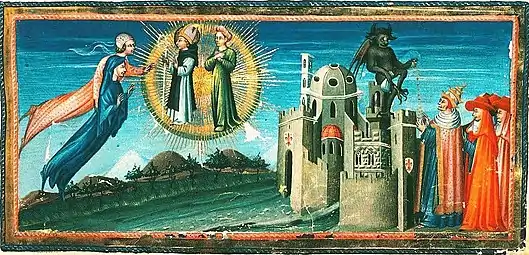

Dante Alighieri had likely learned of the da Romano family through Guido Cavalcanti, since Guido’s father had hosted one of Cunizza’s legal proceedings. Dante also stayed at the court of the degli Scagligeri in Verona, the family who succeeded Ezzelino III after his death.[8]

Cunizza da Romano appears in Canto IX of Dante’s Paradiso. She dwells in the heaven of Venus, while her brother Ezzelino III resides in the blood river Phlegethon, in the seventh circle of Inferno among the violent. The differing nature between people is a concept that Dante explores when speaking with Charles Martel of Anjou, and it has been suggested that Cunizza and Ezzelino embody an application of this concept.[9]

In Paradiso, Venus is a lower realm of heaven which is closer situated to Earth and its sin. Dante’s placement of Cunizza is attributed to her various liaisons and marriages, a Venusian love in Dante’s eyes.[10] In her monologue to Dante, Cunizza expresses her lack of remorse for her carnal sins:

Both he and I were born of one same root:

Cunizza was my name, and I shine here

because this planet’s radiance conquered me.

But in myself I pardon happily

the reason for my fate; I do not grieve

and vulgar minds may find this hard to see.— Dante Alighieri (trans. Allen Mandelbaum), Paradiso IX.31-36

Cunizza’s sin, now existing as divine love, is a transformation that Dante uses for multiple figures in Paradiso besides her. She acknowledges that her dwelling in Paradiso may come as a scandalous surprise to the mortals on Earth,[11] since medieval Christianity scholarship didn’t portray heaven as a space which accepts erotic love or those who experienced it.[12] There has been debate on whether Cunizza has overcome her desires because she explicitly accepts her former flaws, a rare instance in the Divine Comedy. Commentators have noted these discussions to have arisen from interpreting Cunizza’s introduction incorrectly; when she says Venus “conquered” her, the essence of Venus is divine love, rather than the carnal desires that are often paired with Venus.[13]

Cunizza is additionally tasked with discussing the corruption of the March of Treviso and northeastern Italy. She prophesizes that Cangrande I della Scala, Dante's leading patron, will assume control of Treviso as absolute autocrat, after its current ruler, Rizzardo da Camino, is killed. She also foresees Alessandro Novello, a bishop at Feltre, turning three Ghibelline brothers over to the Ferrarese Guelphs to be executed, after offering the brothers protection.[14]

In other works

A fictionalized account of the courtship between Riccardo and Cunizza, one with quite a different outcome, forms the basis for Giuseppe Verdi's first opera, Oberto conte di San Bonifacio.[15]

Cunizza is mentioned in both Robert Browning's Sordello and Ezra Pound's Cantos.

References

- Silverman, Diana C. (2011). "Marriage and Political Violence in the Chronicles of the Medieval Veneto". Speculum. 86 (3): 652–687. doi:10.1017/S003871341100114X. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 41408938. S2CID 162963536.

- "Cunizza da Romano". La Divine Comédie (in French). Retrieved 2021-03-31.

- Goito), Sordello (da; Lollis (1896). Vita e poesie di Sordello di Goito (in Italian). M. Niemeyer.

- Padova, Rolandino da; Padova), Rolandino (da (2004). Vita e morte di Ezzelino da Romano: cronaca (in Italian). Fondazione Lorenzo Valla. ISBN 978-88-04-52727-5.

- Pagliarini, Battista (1990). Cronicae (in Latin). Editrice Antenore.

- Smereglo, Niccolò (1921). Annales civitatis Vincentiae (in Italian). N. Zanichelli.

- Storia degli Ecelini di Giambatista Verci. Tomo primo [-terzo] (in Latin). 1779.

- "Cunizza da Romano". La Divine Comédie (in French). Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- "Tenzone". webs.ucm.es. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- Gardner, Edmund G. (1913). Dante and the Mystics: A Study of the Mystical Aspect of the Divina Commedia and Its Relations with Some of Its Mediaeval Sources. J. M. Dent & sons Limited.

- "Ethics, Politics and Justice in Dante". UCL Press. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- Williams, Pamela (2007). Through Human Love to God: Essays on Dante and Petrarch. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-905886-40-1.

- Hede, Jesper (2007). Reading Dante: The Pursuit of Meaning. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2196-2.

- "Dante Lab at Dartmouth College: Reader". dantelab.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- "Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio". giuseppeverdi.it. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02.

Sources

- Barbara Reynolds, Dante: The Poet, the Political Thinker, the Man, I.B.Tauris, 2007, ISBN 1-84511-554-6, p. 12