Currach

A currach (Irish: curach [ˈkʊɾˠəx]) is a type of Irish boat with a wooden frame, over which animal skins or hides were once stretched, though now canvas is more usual. It is sometimes anglicised as "curragh".

The construction and design of the currach are unique to the west coasts of Ireland. It is referred to as a naomhóg [n̪ˠèːˈvoːɡ] in counties Cork, Waterford and Kerry and as a "canoe" in West Clare. It is similar to the coracle, though the two originated independently. The plank-built rowing boat found on the west coast of Connacht is also called a currach or curach adhmaid ("wooden currach"), and is built in a style very similar to its canvas-covered relative. Folk etymology has it that naomhóg means "little holy one", "little female saint", from naomh, Munster pronunciation [n̪ˠeːv] "saint, holy", and the feminine diminutive suffix -óg). Another explanation is that it comes from the Latin navis, and it has also been suggested that it derives from the Irish nae, a boat.[1]

A larger version of this is known simply as a bád iomartha (rowing boat). It is suggested that the prototype of this wooden boat was built on Inishnee around 1900 and based upon a tender from a foreign vessel seen in Cleggan harbour. These wooden boats progressively supplanted the canvas currach as a workboat around the Connemara coast.[2] This rowing currach measured up to 20 feet, and is still seen in water in North Donegal.

The currach has traditionally been both a sea boat and a vessel for inland waters. The River currach was especially well known for its shallow draft and manoeuvrability. Its framework was constructed of hazel rods and sally twigs, covered by a single ox-hide, which not only insulated the currach, but also helped dictate its shape. These currachs were common on the rivers of South Wales, and in Ireland were often referred to as Boyne currachs. However, when Ireland declared the netting of salmon and other freshwater fish illegal in 1948, it quickly fell out of use.

History

During the Neolithic period,[3] the first settlers landed in the northern part of Ireland, likely arriving in boats that were the ancestors of the currach. Development in joining methods of wood during the Neolithic period made it possible to eventually create what the currach is today. Hide-covered basket origins are evident in currachs found in the east of Ireland, and using the skins for lining currachs in the Neolithic period likely was how the early Irish were able to make their way over to the Irish Isles.[4]

The currach represents one of two traditions of boat and shipbuilding in Ireland: the skin-covered vessel and the wooden vessel. The flimsy construction of the former makes it unlikely that any remains would be available for the marine archaeologist, but its antiquity is clear from written sources.

One of these is the Latin account of the voyage of St Brendan (who was born c. 484 in the southwest of Ireland): Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis. This contains an account of the building of an ocean-going boat: using iron tools, the monks made a thin-sided and wooden-ribbed vessel sicut mos est in illis partibus ("as the custom is in those parts"), covering it with hides cured with oak bark. Tar was used to seal the places where the skins joined. A mast was then erected in the middle of the vessel and a sail supplied.[5] Though the voyage itself is essentially a wonder-tale, it is implied that the vessel as described was built in accordance with ordinary practice at the time. An Irish martyrology of the same period says of the Isle of Aran that the boat commonly used there was made of wickerwork and covered with cowhide.[6]

Tim Severin constructed such a ship, following as best they could the Brendan descriptions and drawing on the skills and knowledge of a few traditional craftsmen, and showed that the result was quite seaworthy by sailing it from Ireland to the new world.

Gerald of Wales, in his Topographia Hibernica (1187), relates that he was told by certain seamen that, having taken refuge from a storm off the coast of Connacht, they saw two men, long-haired and scantily clad, approaching in a slender wickerwork boat covered in skins. The crew found that the two spoke Irish and took them on board, whereupon they expressed amazement, never before having seen a large wooden ship.[7]

The consistency in accounts from the early Middle Ages to the early modern period makes it likely that the construction and design of the currach underwent no fundamental change in the interval.

A 17th-century account in Latin by Philip O'Sullivan Beare of the Elizabethan wars in Ireland includes a description of two currachs built in haste to cross the River Shannon. The larger was constructed as follows: two rows of osiers were thrust in the ground opposite each other, the upper ends being bent in to each other (ad medium invicem reflexa) and tied with cords, whereupon the frame so made was turned upside down. Planks, seats and thwarts were then fitted inside (cui e solida tabula, statumina, transtraque interius adduntur), horse hide was fixed to the exterior and oars with rowlocks were supplied. This vessel is described as being able to carry 30 armed men at a time.[8]

Relationship with the coracle

The currach bears a close resemblance to the coracle, a similar circular boat used in parts of the UK and to the wide family of circular boats termed "coracles" common throughout South and Southeast Asia. These non-Irish coracles all ultimately trace their origin to the quffa, a round Iraqi riverboat dating to the 9th century BCE, or possibly even as early as the 2nd millennium BCE.[9] The resemblances between the currach and the coracle and quffa are a coincidence, however. British ethnologist James Hornell, who studied the currach, coracle, and quffa extensively during the early 20th century, believes that the currach was developed independently of the coracle and quffa in a case of multiple invention.[10]

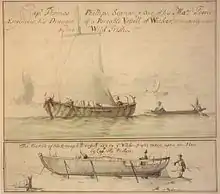

Sea-going currachs, c. 17th century

The construction and sailing of a seagoing curach of the 17th century, a hybrid of the skin-covered and plank-built boat, was depicted in some detail by an Englishman, Captain Thomas Phillips: "A portable vessel of wicker ordinarily used by the Wild Irish".[11]

Though doubt has been cast on the accuracy of these sketches,[12] they are detailed and represent a valid development of the ocean-going currach. The vessel is some twenty feet long: it possesses a keel and a rudder, with a ribbed hull and a mast amidship. Because of the keel, the craft is shown as being constructed from the bottom up. A covering (presumably of animal hides) was added, the sides being supported by rods in the interval.

The mast is supported by stays and by double shrouds on each side, the latter descending to an external shelf functioning as a chainwale. The forestay is shown as passing over a small fork above the yardarm, which supports a square sail: a branch is tied to the mast-top. The stern is surmounted by double half-hoops which could support a covering.

The sketches by Phillips imply that such a vessel was common in his day. The keel would improve the handling of the boat[13] but the hull would remain flexible.

Modern Irish currach

Currachs in general adhere to a plan designed to produce a sturdy, light and versatile vessel. The framework consists of latticework formed of rib-frames ("hoops") and stringers (longitudinal slats), surmounted by a gunwale. There are stem and stern posts, but no keel. Thwarts are fitted, with knees supplied as required. Cleats or thole pins are fitted for the oars, and there may be a mast and sail, though with a minimum of rigging. The outside of the hull is covered by tarred canvas or calico, a substitute for animal hide.

Currachs were used in the modern period for fishing, for ferrying and for the transport of goods and livestock, including sheep and cattle.[14]

Use of the currach was not continuous or universal along the Atlantic coast. In the modern period it did not reach Kerry (in the southwest of Ireland) until the late 19th century (c. 1880). Until then the only vessel used was the heavy wooden seine boat, which required eight men to row it.[15] The Blasket Islanders found the currach (or naomhóg) particularly useful,[16] and a distinctive regional type developed.

Oldbridge

The Irish River Currach is still being built in Oldbridge at river Boyne. Currachs produced here follow the same general construction process as many other Currach styles but in Boyne they implement the use of tarred canvas as the outer layer.[17]

Donegal

Detailed plans are available for Donegal currachs.

The Donegal Sea Currach is very similar to the Boyne Currach in construction and style although the two are produced on opposite coasts from each other. The Donegal Sea Currach is the last traditional Irish craft to use the free paddle instead of the traditional oar.[17]

Mayo

South Mayo currachs differ from most other currach types in that, instead of the stringers which elsewhere run outside the latticework frame, the bottom and sides are covered with a thin planking. In Achill Island the currach is built with double gunwales.[18]

Connemara and the Islands

The Connemara currach is also distinguished by a double gunwale and by a particular form of pivoting block or "bull" attached to one side of the squared region of the loom of the oar.

The Aran islanders, like the Blasket islanders further south, were assiduous users of the curach. Unusually for the area a sail was used, though without shrouds or stays. Apart from the halliard, the only ropes were the tack, led to a point near the stem, and the sheet, carried aft and secured to the last thwart.[19]

Currach races remain popular. In the mid-1950s and early 1960s the Seoighe cousins excelled by winning many county and All Ireland championships, including three in a row of the latter.

Clare

The Clare currach closely resembled that of the Aran Islands. In construction, a series of wooden markers were sunk into the ground at definite distances apart. These helped show the width desired for the lower gunwale frame. This was constructed first, followed by the upper frame, and the thwarts were then nailed into place.[20]

Shannon

Currachs covered in cowhide were still common in the 1840s above Lough Ree, in the centre of Ireland. Thereafter they disappeared except at the seaward end of the Shannon Estuary.[21]

Kerry

Kerry currachs had a reputation for elegance and speed. All were fitted for sailing, with a short mast without shrouds stepped in a socket in a short mast shoe. The halliard was rove through an iron ring near the masthead, hoisting a small lug sail, and this was controlled by a sheet and tack. When under sail lee-boards might be employed.[22]

Currach builders

Currently there are few full-time currach builders. A notable exception are Meitheal Mara, who build currachs and train in currach building in Cork. They also organise currach-racing.

There has been a community-based enterprise in West Clare since 2005 called West Clare Currachs,[23] with support from James Madigan of the Ilen School, Limerick. LNBHA,[24] a community group on Lough Neagh, has made a number of Kerry naomhógs and Dunfanaghy and Tory Island currachs. In other counties on the western seaboard there are boat builders who sometimes make currachs.

Scottish currachs

The traditional Scottish currach is nearly extinct, but there are occasional recreations. It is known to have been in use on the River Spey, in the north east, and also in the Hebrides.

St Columba

St Columba is said to have used a currach.

- "On a day, at the end of two years from his arrival on Iona, Columba goes to the beach, where his craft of wicker and cowhide lies moored, waiting the use of any member of the community of Hy whose occasions may call him away from the island. He is accompanied by two friends and former fellow-students, Comgal and Cainnech, and followed by a little escort of faithful attendants. Taking his seat in his currach, he and his party are rowed across the sound to the mainland."[25]

St Beccan of Rùm may have lived on the island for four decades from 632 AD, his death being recorded in the Annals of Ulster in 677.[26] He wrote of Columba:

- In scores of curraghs with an army of wretches he crossed the long-haired sea.

- He crossed the wave-strewn wild region,

- Foam flecked, seal-filled, savage, bounding, seething, white-tipped, pleasing, doleful.[27]

Currachs in the River Spey

In the Statistical Account of Scotland of 1795 we read of

- "[a] man, sitting in what was called a Currach, made of hide, in the shape, and about the size of a small brewing-kettle, broader above than below, with ribs or hoops of wood in the inside, and a cross-stick for the man to sit on. . . . These currachs were so light, that the men carried them on their backs home from Speymouth."

The Spey currach would thus seem to be similar to the Welsh coracle in design, being used on a river rather than in the open sea. But twenty years earlier, we read of bigger ones, in Shaw's History of the Province of Moray (1775):

- "Let me add, as now become a Rarity, the Courach. . . . It is in shape oval, near three feet broad, and four long."

A more detailed description can be found in Scottish court records (1780):

- "The currach contained only one man in working it, whereas the floats require two men and oars; and the man in the currach paddled with a shovel, one end of the rope being fixed to the raft, and the other tied to the man's knee in the currach, which he let loose when there was any danger, the currach going before the raft."

Spey currachs were used in the timber trade there, as described in Ainslie's Pilgrimage etc. (1822):

- "The river taking a sudden bend, broadened and deepened into a wheel, on the breast of which a salmon cobble, or currach swam.

- "Hence curracher, a man who sat in a currach and guided floating timbers down the Spey."

These may have survived into twentieth century; there is a reference to a "currick" in the Banffshire Journal (1926).

Current use as racing boats

Currachs survive now as racing boats, often holding their own against much more modern types. In the annual London Great River Race,[28] Currachs have regularly performed outstandingly in the Overall rankings (fastest boat on handicap), notably in 2007,[29] 2008,[30] and 2010.[31]

A currach entered the inaugural Race to Alaska in 2015.[32][33] The West Kerry naomhóg, with two Canadian crew members, attempted the 1,200 kilometre no-motor trip up the Inside Passage from Port Townsend, WA, to Ketchikan, AK.

Currach races are also performed at the Milwaukee Irish Fest. This event is held by the Irish Currach Club of Milwaukee in late August of every year and it features two races that are available for the public to view during the festival.[34]

Currach races are also hosted in Albany, NY; Annapolis, MD; Boston, MA; Leetsdale, PA; New London, CT; Pittsburgh, PA and Philadelphia; PA as part of the North American Currach Association.[35]

See also

Notes

- Ua Maoileoin, p. 143.

- Mac an Iomaire (2000), Annotation by translator Padraic de Bhaldraithe p. 37

- "Neolithic - Definition of Neolithic in English by Lexico Dictionaries". Lexico Dictionaries - English. Archived from the original on 16 June 2019.

- "A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland". www.libraryireland.com.

- Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis, cap. IV: http://www.hs-augsburg.de/~harsch/Chronologia/Lspost10/Brendanus/bre_navi.html

- Quoted in Hornell (1977), p. 17: Erat enim in istis partibus, eo aevo, quoddam navigii genus usitatum, ex viminibus contextum, et bovinis coriis contectum; quad Scotica lingua Curach appellatur.

- Topographia Hibernica, Dist. III, Cap. XXVI: http://www.maryjones.us/ctexts/index_latin.html. A translation can be found at: http://www.yorku.ca/inpar/topography_ireland.pdf. The Latin passage, of great ethnological interest, is as follows: Audivi enim a navibus quibusdam, quod cum quadrogesimali quodam tempore ad boreales et inexscrutabiles Connactici maris vastitates vi tempestatis depulsi fuissent, tandem sub insula quadam modica se receperunt: ubi et anchorarum morsu, funiumque triplicium, immo multiplicium tenacitate se vix retinuerent. Residente vero infra triduum tempestate, et restituta tam eari serenititae quam mari tranquillitate, apparuit non-procul facies terrae cujusdam, eis hactenus prorsus ignotae; de qua non-longe post et cymbulam modicam ad se viderunt remigantem, arctam et oblongam, vimineam quidem, et coriis animalium extra contextam et consutam. Erant autem in ea homines duo, nudis omnino corporibus, praeter zonas latas de crudis animalium coriis quibus stringebantur. Habebant etiam Hibernico more comas perlongas et flavas, trans humeros deorsum, corpus ex magna parte tegentes. De quibus cum audissent, quod de quadam Connactiae parte fuissent, et Hibernica lingua loquerentur, intra navem eos adduxerunt. Ipsi vero cuncta quae ibi videbant tanquam nova admirari coeperunt. Navem enim magnam et ligneam, humanos etiam cultus, sicut asserebant, nunquam antes viderant..

- O'Sullivan-Beare, Philip, Historia catholicae Iberniae compendium, Tom III., Cap IX: https://archive.org/stream/MN42000ucmf_1/MN42000ucmf_1_djvu.txt (though there are a number of errors in the transcription). For a translation of the work, see http://www.ucc.ie/celt/published/T100060/index.html.

- Kennedy, Maev (1 January 2010). "Relic reveals Noah's ark was circular". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- Hornell (1939), pp. 13

- This is preserved in the Pepysian Library, Cambridge. See the discussion by Nance, R. Morton, "Wicker Vessels", The Mariner's Mirror, July 1922

- Hornell (1977), pp. 35–36

- See Ua Maoileoin, pp. 141–142, on the difficulty of tacking in a keel-less modern currach: Ar a tosach a choimeád sa bhfarraige agus gan í a ligeant i leith a cliatháin uirthi, is maith an bléitse farraige a chuirfeadh síos í. Agus tá iompar seoil inti ná cuirfeá féna tuairim in aon chor, ach aon ní amháin, gan aon chille a bheith fúithi agus nach féidir aon bhordáil, puinn, a dhéanamh léi ach roimis an ngaoith i gcónaí agus í ag imeacht leathchliathánach...

- Tyers (ed.), pp. 94–95: Seán Ó Criomhthain describing how the feet of cattle were secured to keep them subdued in transit: Chaithfeá iad seo a leagadh agus na ceithre cosa a cheangal dá chéile, agus a fhios a bheith agat conas a cheanglófá leis iad, agus téadán maith a bheith agat. Iad a bhualadh isteach ansin sa naomhóg, agus, má chífeá aon bhogadh ag na cosa á dhéanamh, teacht agus an cupán, áras atá ag leanúint na naomhóige, a chur anuas don uisce, agus cúpla maith uisce a dhoirteadh anuas ar an téad, agus d'fháiscfeadh sé sin go maith ar a chéile iad.

- Ua Maoileoin, pp. 140–146

- Tyers (ed.) pp. 29–30

- OtherLives (6 December 2008). "Hands Curragh Makers Part 1" – via YouTube.

- Hornell (1977), pp. 5–13

- Hornell (1977), pp. 13–23

- Hornell (1977), pp. 24–28

- Hornell (1977), pp. 28–29

- Hornell (1977), pp. 29–35

- "Water Based Activities - Activities - West Clare Currach Club - Kilkee - County Clare Tourism Website". 18 May 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

- "Boat Building Workshops". www.an-creagan.com.

- Quoted in Wylie

- Rixson (2001) op cit pages 21 – 25.

- "Tiugraind Beccain" in Clancy, T.O. and Markus, G. eds. (1995) Iona- The Earliest Poetry of A Celtic Monastery, quoted by Rixson (2001) op cit page 25.

- The Great River Race every September covers 21 miles (34 km) from Millwall in the Docklands up to Richmond; for the faster boats, it usually takes about three hours to row with the tide. It is open to every kind of rowed or paddled boat, from skiffs up to row-barges and dragon-boats, and currently (2012) attracts over 300 entrants.

- 2007 results 3rd overall: Coonagh Crew, a Clare Fishing Currach (3 hd)

- 2008 results 1st overall: The Sin Bin, a Connemara Currach (3 hd)

- 2010 results 2nd overall: Leaper, a Racing Naomhóg (4 hd)

- "Boats and Books – March Update". Angus Adventures. 17 March 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- "Race to Alaska | Full Race Participants". Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "Sports - Milwaukee Irish Fest". irishfest.com.

- https://www.facebook.com/NACArowing

References

- Hornell, James (11 February 1939), "British Coracles and Irish Curraghs: with a Note on the Quffah of Iraq", Nature, 143 (224): 224, Bibcode:1939Natur.143R.224., doi:10.1038/143224c0, ISSN 1476-4687

- Hornell, James (1977), British Coracles and Irish Curraghs (first ed.), New York: Ams Press Inc, ISBN 978-0-404-16464-5 Extract dealing with the Irish Currach

- Ua Maoileoin, Pádraig (1970), Na hAird ó Thuaidh (second ed.), Baile Átha Cliath: Sáirséal agus Dill

- Tyers, Pádraig, ed. (1982), Leoithne Aniar (first ed.), Baile an Fheirtéaraigh: Cló Dhuibhne

- Mac an Iomaire, Séamas (2000), The Shores of Connemara (first ed.), Newtownlynch, Kinvara: Tir Eolas, ISBN 978-1-873821-14-5

- Ainslie, H. Pilgrimage etc. (1822)

- Banffshire Journal (18 May 1926)

- Dwelly, Edward Faclair Gàidhlig agus Beurla

- Shaw, L History of the Province of Moray (1775)

- Session Papers, Grant v. Duke of Gordon (22 April 1780)

- Statistical Account of Scotland (1795)

- Wylie, Rev. J.A. History of the Scottish Nation, Vol. 2 (1886)