Curtain Theatre

The Curtain Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse located in Hewett Street, Shoreditch (within the modern London Borough of Hackney), just outside the City of London. It opened in 1577, and continued staging plays until 1624.[1]

| Address | 18 Hewett Street London England |

|---|---|

| Years active | 1577–1622? |

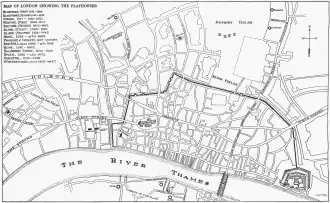

The Curtain was built some 200 yards (180 m) south of London's first playhouse, The Theatre, which had opened a year before, in 1576. It was called the "Curtain" because it was located near a plot of land called Curtain Close, which derived its name in turn from its proximity to the walls of Holywell Priory, a curtain wall being a section of wall between two bastions.[2][3] (The name bears no relationship to the front curtain associated with modern theatres.) The remains of the theatre were rediscovered in archaeological excavations in 2012–16. The most significant revelation was that the Curtain was rectangular, not round. The excavation revealed a 14-metre (46 ft) stage, and evidence of a tunnel under the stage and galleries at the first floor level. Small finds included a ceramic bird whistle; ceramic money boxes for collecting entry fees; beads probably used for decorating stage costumes; and a small statue of Bacchus.

History

The Curtain Theatre was built in 1577 in Shoreditch, and was London's second playhouse. The name derives from the curtain wall of the adjacent St John the Baptist Holywell monastery.[3] Little is known of the companies that performed there, or of the plays they performed. The first clear mention of the Curtain is in 1584, when the City of London petitioned the parish of Shoreditch to shut down their playhouses.[4]: 63 The proprietor appears to have been Henry Lanman, described as a "gentleman": in 1585, Lanman made an agreement with the proprietor of the Theatre, James Burbage, to use the Curtain as a supplementary house, or "easer," to the more prestigious older playhouse. From 1597 to 1599, it became the premier venue of Shakespeare's Company, the Lord Chamberlain's Men, who had been forced to leave their former playing space at The Theatre after the latter closed in 1596. It was the venue of several of Shakespeare's plays, including Romeo and Juliet (which gained "Curtain plaudits") and Henry IV Part I and Part II. The Lord Chamberlain's Men also performed Ben Jonson's Every Man in His Humour here in 1598, with Shakespeare in the cast.[5] Later that same year Jonson gained a certain notoriety by killing actor Gabriel Spencer in a duel in nearby Hoxton Fields.

The Lord Chamberlain's Men departed the Curtain when the Globe Theatre, which they built to replace the Theatre, was ready for use in 1599.[6] For seven years Henry Lanman (owner of the Curtain) had an agreement with James Burbage (owner of the Theatre) that all profit would be shared between them. This deal is how many believe Lanman was able to afford to open the Curtain, the rest is all very unclear. J. Leeds Barroll focuses in Shakespeare studies: An annual gathering of Research, Criticism and Reviews on the fact that Henry Lanman had offered the Curtain as an easer to James Burbage, proprietor of the Theatre. Thereby, he assumes that Lanman’s business, the Curtain, must have been doing as well as Burbage’s business, the Theatre, since both, Lanman and Burbage, had agreed on a pooling arrangement for seven years in 1585, to pool profits. As far as is known, Lanman ran the Curtain as a private concern for the first phase of its existence; He died in 1606[7] and it is assumed by Edmund Chambers that the theatre had been re-arranged into a shareholder’s enterprise before his death at some point. Thomas Pope, one of the Lord Chamberlain's Men, owned a share in the Curtain and left it to his heirs in his last will and testament in 1603. King's Men member John Underwood did the same in 1624.[4]: 63 [8] The fact that both of these shareholders belonged to Shakespeare's company may indicate that the re-organization of the Curtain occurred when the Lord Chamberlain's Men were acting there. Otherwise, it would be very unwise of Burbage to pool profits if he did better in the first place. Thus, the suggestion is given that both proprietors were doing equal business. Burbage's father James had shares in the theatre at the time of his death.[9]: 144

The London theatres, including the Curtain, were closed for much of the period from September 1592 to April 1594 due to the bubonic plague.[10] In 1597, people wrote to the local magistrates' court demanding that no plays take place at the Curtain or the Theatre that year.[9]: 37 The Curtain was named in John Stow's Survey of London in 1598, but was not listed in the 1603 edition.[11] In 1600, the Privy Council tried unsuccessfully to shut down the Curtain theatre,[4] and in 1603, the Curtain became the playhouse of Queen Anne's Men (formerly known as Worcester's Men, and formerly at the Rose Theatre, where they'd played Heywood's A Woman Kill'd With Kindness in February of that year).[4]: 64 In 1607, The Travels of the Three English Brothers, by Rowley, Day, and Wilkins, was performed at the Curtain.

The Curtain was in use from 1577 until at least 1624, after which its ultimate fate is obscure as there is no record of it after 1627. The reasons for its closure are not known.

Site and rediscovery

The Curtain was believed to have been built near The Theatre, but the exact location was for many years unknown.[12][13] However, a commemorative plaque was erected at 18 Hewett Street.[4]: 62 [14]

In 2012, archaeologists from MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) announced that they had discovered the remains of the theatre during trial excavations.[15][16] In 2013 plans were submitted to develop the site with a 40-storey tower of 400 apartments, plus a Shakespeare museum, 250-seat outdoor auditorium and park, with the archaeological remains visible in a glass enclosure.[17]

In May 2016, excavators announced that the theatre was purpose-built and, unusually, was a rectangle (measuring 22×25 metres) rather than being round or polygonal.[3] Walls survived up to 1.5 metres (5 ft) high in places; MOLA identified the courtyard, where theatregoers stood, and the inner walls, which held the galleries.[18] The theatre had timber galleries with mid and upper areas for wealthier audience members, and a courtyard made from compacted gravel for those with less to spend.[19] The galleries were straight.[3]

Also uncovered was a fragmentary ceramic bird whistle, dating from the late 16th century. This raised the question of whether the bird whistle was merely a Tudor toy or a prop for plays that needed sound effects.[20] In November 2016, a tunnel structure – accessed by doors on either end of the stage – was unearthed, which would have allowed actors to exit from one side and come on again from the other without being seen by the audience.[21] Fragments of ceramic money boxes were found, which would have been used to collect entry fees from theatregoers, before being taken to an office to be smashed and the money counted: this office was known as the "box office", which is the origin of the term we use today.[22]

Glass beads and pins were unearthed along with drinking vessels and clay pipes.[23] The team also came across a mount and a token,[24] as well as personal items, including a bone comb.[25]

In August 2019 the structural remains and below-ground deposits were designated a Scheduled Monument.[3] The high-rise residential tower block on the site is named "The Stage"; and the two adjacent low-rise office blocks "The Bard" and "The Hewett".[26]

In popular culture

A reconstruction of the Curtain Theatre features in the 1998 film Shakespeare in Love.[27]

The theatre is also featured as the main setting for the jukebox musical & Juliet, which takes place during the first performance of Romeo and Juliet.

Notes

- Bawcutt, N. W. (1996). The Control and Censorship of Caroline Drama: The Records of Sir Henry Herbert, Master of the Revels, 1623–1673. Oxford: Clarendon. pp. 141, 150. ISBN 9780198122463.

- Joseph Quincy Adams, Shakespearean Playhouses, Boston, 1917, p. 76.

- "The Curtain Playhouse". historicengland.org.uk. 16 August 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Bowsher, Julian (July 2012). Shakespeare's London Theatreland: Archaeology, History and Drama. Museum of London Archaeology. ISBN 9781907586125.

- E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage volume III, Oxford, 1923, p. 359.

- Stern, Tiffany (February 2004). Making Shakespeare: From Stage to Page. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-0415319652. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- William Ingram, The Business of Playing: The Beginnings of the Adult Professional Theater in Elizabethan London, Cornell University Press, 1992, p. 222.

- Chambers, Vol. 2, p. 403.

- Collier, John Payne (2012). The works of William Shakespeare. General Books. ISBN 9780217290210. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- Chambers 1930, pp. 44–7.

- Smith, David L.; Strier, Richard; Bevington, David (2002). The Theatrical City: Culture, Theatre and Politics in London, 1576-1649. Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 0521526159.

- "The Curtain". Shakespeare Online. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "Curtain Elizabethan Theatre". Elizabethan Era Online. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- "The Curtain Theatre". London Borough of Hackney. 28 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "Remains of Shakespeare's Curtain Theatre discovered in Shoreditch" (Press release). Museum of London Archaeology. 6 June 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- Kennedy, Maev (5 June 2012). "Shakespeare's Curtain theatre unearthed in east London". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- "Curtain lifts on open-air stage at Shakespeare theatre site in Shoreditch". Evening Standard. 24 January 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Bishop, Rachel (18 May 2016). "500-year-old Romeo And Juliet prop found in dig at Shakespeare's Curtain Theatre". mirror. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Broadbent, Giles (15 November 2016). "Will theatre revelations shed light on Shakespeare's secrets?". thewharf. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Furness, Hannah (18 March 2016). "Bird whistle from first Romeo and Juliet". The Daily Telegraph.

- Kennedy, Maev (10 November 2016). "Did Shakespeare write Henry V to suit London theatre's odd shape?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- Loeb, Josh (10 November 2016). "Mysteries unearthed in Shoreditch excavation of Shakespeare's Curtain Theatre". Hackney Citizen. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "Shakespeare clues found after Shoreditch exacerbation". Evening Standard. 10 November 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "Archaeologists reveal initial findings from detailed excavation at Shakespeare's Curtain Theatre – HeritageDaily – Heritage & Archaeology News". Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "Shakespeare Curtain Theatre: Remains reveal toy used for sound effects". BBC News. 17 May 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "The Stage.Ldn, Shoreditch". The Stage.Ldn, Shoreditch. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Shakespeare in Love (1998) at IMDb

References

- Chambers, Edmund K. (1923). The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Chambers, Edmund K. (2009). The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 5. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chambers, Edmund Kerchever (1930). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. Vol. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 353406.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1987) William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. OUP.

- Shapiro, J. (2005) 1599: A Year in the Life of Shakespeare. Faber and Faber.

- Wood, M. (2003) In Search of Shakespeare. BBC Worldwide.

.png.webp)