Isaiah Oggins

Isaiah Oggins (also known as Ysai or Cy) (July 22, 1898 – 1947) was an American-born communist and spy for the Soviet secret police. After working in Europe and the Far East, Oggins was arrested, served eight years in the GULAG detention system, and was summarily executed on the orders of Joseph Stalin.[1][2]

Isaiah Oggins | |

|---|---|

| Born | Isaiah Oggins July 22, 1898 |

| Died | 1947 (aged 49) |

| Cause of death | Poisoning by curare |

| Burial place | Penza, USSR (now Russia) (as claimed by USSR) |

| Other names | Cy Oggins, "Professor" |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | Columbia University |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Known for | Soviet espionage |

| Spouse | Nerma Berman |

| Children | 1 |

| Espionage activity | |

| Allegiance | Soviet Union |

| Agency | GRU or NKVD |

| Service years | 1926–1939 |

| Codename | Egon Hein |

Background

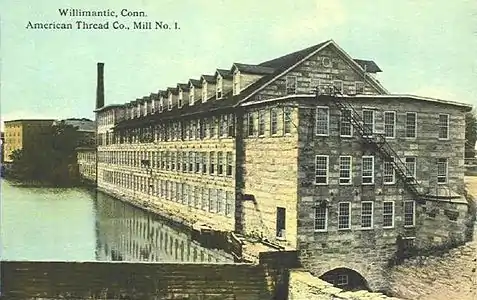

The third of four children, Oggins was born 1898 in the mill town of Willimantic, Connecticut, the son of Simon Melamdovich (who changed his name to "Oggins" in America) and his wife Rena, both Jewish immigrants from the Abolnik shtetl near Kovno (Kaunas), Lithuania. Oggins's parents arrived in New York in 1888. They had three other children.[1]

Oggins entered Columbia University in February 1917 under current Jewish quota policies. Classmates included publishers Bennet Cerf, Donald Klopfer, and Richard Simon; historian Matthew Josephson; novelist Louis Bromfield, critic Kenneth Burke, and author William Slater Brown. Professors included John Erskine, George Odell, Robert Livingston Schuyler, and Charles A. Beard. After receiving his B.A. in history, he began a doctorate in history while working at history reader there, then in a night school in the New York Public School system.[1][3]

Career

In 1923, Oggins became a Communist by joining the Workers Party of America. The same year, he changed jobs to work for Yale University Press as a researcher.[1]

Soviet underground espionage

As of August 26, 1926, when he applied for his U.S. passport, Oggins had joined the Soviet underground and was readying for his first overseas assignment, probably in Germany and France. In April 1928, his wife Nerma applied for her first U.S. passport. The couple departed from New York on May 5, 1928, for a villa in the Zehlendorf district of Berlin, Germany. They reported to Ignace Reiss. Their job was to maintain a low profile and inhabit their residence, so that other Soviet agents could periodically use it as a safe house for various espionage related activities. To accomplish this mission, Cy and Nerma had to avoid any appearance of being interested in Communist politics; they had to avoid even reading Communist newspapers. Friend Sidney Hook spotted Oggins in the Gendarmenmarkt, as described in his autobiography Out of Step (1984). Oggins had to resist the temptation to have meetings with his old friend, although he did not always resist this temptation fully.[4][5]

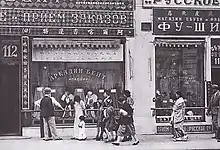

The Ogginses moved from Berlin to Paris in the spring of 1930. In Neuilly-sur-Seine, they watched White Russians, Trotskyites including Trotsky's Paris-based son, Lev Sedov, and the family of Michael Feodorovich Romanov. After exposure of l'affaire Switz (1933–1934, involving Robert Gordon Switz, Lydia Stahl, and Arvid Jacobson[6]), the Ogginses left Paris (September 1934) and returned to the States with their young son Robin (b. 1931). After a brief stint in New York, they left for San Francisco. Leaving his wife and child behind, Cy Oggins set off for China in September 1935, where he served through 1937.[1][2]

In Shanghai, Oggins reported to Grace and Manny Granich (brother of Mike Gold). In 1936, he worked in Dairen during the Manchukuo and traveled to Harbin. He reported to Charles Emile Martin (also known as George Wilmer, Lorenz, Laurenz, Dubois—born Matus Steinberg of Belgorod-Dnestrovsky) and wife Elsa Marie Martin (also known as Joanna Wilmer, Lora, Laura). (Martin later served in the Red Orchestra, spying on Nazi Germany.) By October 1937, the Martins and Ogginses fled separately after Chiang Kai-shek attacked Manchuria in July.[1]

Oggins rejoined his wife and son in Paris in February 1938, only to leave again in May. Nerma Berman Oggins left Paris with their son in September 1939 and returned to New York.[1] (The State Department believes he was stationed in France in 1937–1938.[2])

GULAG

On February 20, 1939,[2] the Soviet NKVD arrested Oggins at the Hotel Moskva and took him to the Lubyanka, accusing him of being a traitor. His case received a hearing on January 5, 1940.[2] Ten days later, he received a sentence of eight years.[1]

On the next day, Oggins shipped out to Norillag,[2] where fellow inmates included Jacques Rossi. He became known there as "The Professor". Nerma Berman Oggins requested the U.S. Department of State to investigate her husband's disappearance. On April 15, 1942, the US Department of State indicated to the US embassy in Moscow "It is possible that he [Oggins] has been acting for years as an agent of a foreign power or of an international revolutionary organization. Nevertheless it is believed that in view of his American citizenship and of the Soviet agreement in 1933 to inform this Government of the arrest of American citizens, the failure to report his detention should not be ignored."[2] On June 30, 1942, US Secretary of State Cordell Hull had the following telegram sent to the US ambassador in Moscow:

Washington, June 30, 1942—11 p.m.

327. Your 538, June 16, 1 p.m. Please take up this case informally with the Soviet authorities and since Oggins is an American citizen request permission for an American Foreign Service Officer to visit him as provided for in the 1933 agreement, or that Oggins be allowed to appear at the Embassy.

Without at this time giving emphasis to the failure of the Soviet authorities, from the standpoint of commitments of the Soviet Government, to notify the Embassy of Oggins’ arrest, you may, however, express some surprise at such failure and may mention that your Government hopes that steps will be taken to prevent failures of a similar nature from taking place in the future.

The Department is concerned as to the disposition made of Oggins’ passport.[2]

On December 8, 1942, Oggins received visits from American diplomats at the Butyrka prison in Moscow. By May 1943, the Soviets reneged on his release.[1]

During his time in the GULAG, Oggins's wife and son pled with US Secretary George C. Marshall to help gain his release.[7]

Death

In May 1947, it was decided to murder Oggins because the Soviets feared that if the spy were repatriated to the United States, as the US government had requested, he would defect and reveal Soviet secrets. By mid-summer, Oggins was taken to Laboratory Number One (the "Kamera"), where Grigory Mairanovsky injected him with the poison curare, which takes 10–15 minutes to kill.[1] A death certificate claimed Oggins had died of "sclerosis" and had received burial in a Jewish cemetery in Penza.[7]

Aftermath

FBI investigation

An FBI investigation into the Oggins affair commenced in March 1943. After the defection of Igor Gouzenko, the name "Oggins" arose again in 1945–1946.[1]

On February 10, 1949, FBI investigators questioned Esther Shemitz, wife of Whittaker Chambers, about the Ogginses, as Esther Chambers and Nerma Oggins had both attended the Rand School and had worked at the ILGWU and The World Tomorrow magazine.[1]

Joint Russian–American investigation

In early 1992, the U.S. and Russia formed the U.S.–Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs. Overseeing the investigation was Dmitri Volkogonov. On September 23, 1992, Boris Yeltsin handed an Oggins case dossier to American diplomat Malcolm Toon: Oggins had been liquidated on Stalin's orders.[1][8][9][10][11]

The Lost Spy

In 2008, Andrew Meier, formerly Moscow bureau chief for TIME magazine, published a biography of Oggins called The Lost Spy. The book resulted from a decade of investigative research into the mysterious circumstances of Oggins's imprisonment and death. It included documentation from Soviet, American, and Swiss archives[7][12][13][14][15]

Requests to FSB

Oggins's son has continued to ask for information about his father's death from Soviet successor agencies like the Russian Federal Security Service (generally known by its Russian acronym "FSB").[7]

Personal life

On April 23, 1924, he married Nerma Berman (1898–1995), a Rand School student and Communist activist, born in the Skapiskis shtetl (also near Kovno).[2] She became secretary of the New York division of the National Defense Committee of the Rand School for Red Scare victims Scott Nearing and other professors.[1]

The Oggins had one son, Robin, born 1931.[1][2]

Nerma Berman Oggins drifted from job to job and lived in the New York City area. She retired in 1965 and lived for a time in the Lower East Side at the Henry Street Settlement. She later moved to Vestal, New York to be near her son. She died in Vestal on January 27, 1995.[1]

See also

References

- Meier, Andrew (August 11, 2008). The Lost Spy: An American in Stalin's Secret Service. W. W. Norton. pp. 17–89]. ISBN 978-0-393-06097-3.

- "The Secretary of State to the Ambassador in the Soviet Union (Standley)". United States Department of State. 30 June 1942. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Bookshelf | Columbia College Today". www.college.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-04.

- Hook, Sidney (1984). Out of Step: An Unquiet Life in the 20th Century. Harper and Row. pp. 94–101, Chapter 8, "Encounter with Espionage. ISBN 0-06-015632-5.

- See Meier's book about their time in Berlin

- "France: Two Blonde Hairs". TIME. March 26, 1934. Retrieved 27 July 2021.

- Chivers, C.J. (7 November 2008). "Son Finds Veil on Father's Death Under Stalin Lifting a Bit". New York Times. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Missing Americans segment on ABC Evening News". Vanderbilt Television News Archive. September 23, 1992. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- "Russian Tells of Americans' Fate". New York Times. September 24, 1992. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

- Bohlen, Celestine (September 25, 1992). "Advice of Stalin: Hold Korean War P.O.W.'s". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- Fireman, Ken (September 26, 1992). "Deadly Fate Of 2 Cold War Victims". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2008-08-25.

- Blackman, Ann (10 August 2008). "TLost in the gulag". Boston Globe. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Crispin, Jessa (8 September 2008). "True-Life Spy Story Unfolds Like A Thriller". NPR. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Bookshelf". Columbia College Today. February 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "The Lost Spy: Espionage & Idealism, Before the Cold War". Columbia College Today. 24 September 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2020.