Cyanometer

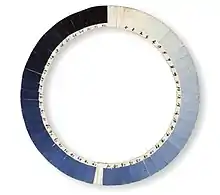

A cyanometer (from cyan and -meter) is an instrument for measuring "blueness", specifically the colour intensity of blue sky. It is attributed to Horace-Bénédict de Saussure and Alexander von Humboldt. It consists of squares of paper dyed in graduated shades of blue and arranged in a color circle or square that can be held up and compared to the color of the sky.

.jpg.webp)

History

De Saussure, a Swiss physicist and mountain climber, is credited with inventing the cyanometer in 1789.[1] De Saussure's cyanometer had 53 sections, numbered cards, ranging from white to varying shades of blue (dyed with Prussian blue) and then to black,[2] arranged in a circle; he used the device to measure the color of the sky at Geneva, Chamonix, and Mont Blanc.[3] De Saussure concluded, correctly, that the color of the sky was dependent on the amount of particles, water droplets and ice crystals, suspended in the atmosphere. Humboldt was also an eager user of the cyanometer on his voyages and explorations in South America.[4]

Theory

The blueness of clear air in Earth's atmosphere is due to Rayleigh scattering by nitrogen and oxygen molecules. Dry air is 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. Atmospheric water content ranges from 0% to 5%.

When looking through clear air toward the horizon, distant sunlight of all wavelengths (colors) will generally undergo Mie scattering from spherical suspended particles. In an unpolluted sky, these spherical particles will primarily be liquid water condensed onto natural atmospheric dust grains. This is known as "wet haze". Therefore, in an unpolluted clear sky, wet haze adds white sunlight to blue Rayleigh-scattered light. More wet haze in the observer's line of sight results in a brighter and paler blue sky color.

When looking toward the horizon, an observer looks through up to 40 times as much atmosphere compared to looking overhead. Therefore, more Mie scattering is seen when viewing parts of the sky closer to the horizon. A darker blue sky will be observed if less wet haze is in the observer's line of sight. This occurs when looking directly overhead and at a higher altitude.

See also

Notes

- H-B de Saussure, Description d'un cyanomètre ou d'un appareil destiné à mesurer la transparence de l'air, Mem. Acad. Roy. Turin, 1788-89, 4, 409

- "Saussure's cyanometer". Royal Society of Chemistry.

- Lilienfeld, Pedro (2004). "A Blue Sky History". Optics and Photonics News. 15 (6): 32–39. doi:10.1364/OPN.15.6.000032.

- Hoeppe, Götz (2007). Why the sky is blue: discovering the color of life. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-691-12453-7.

References

- Heubner (1840). "Über das Cyanometer". Zeitschrift für Physik und verwandte Wissenschaften. 6: 201.

- Hermann von Schlagintweit, Adolf Schlagintweit (1850). Untersuchungen über die physicalische Geographie der Alpen in ihren Beziehungen zu den Phaenomenen der Gletscher, zur Geologie, Meteorologie und PflanzengeographieBarth. p. 441.

- Lord Byron alludes to this device in his satirical verse epic Don Juan (Canto IV, 112 ) as an ironical means of measuring the blue of bluestocking ladies.

External links

- Saussure's cyanometer, from the Royal Society of Chemistry. Accessed Nov. 19, 2010. Includes a picture of the cyanometer which now lives in the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.

- The Cyanometer Is a 225-Year-Old Tool for Measuring the Blueness of the Sky, by Christopher Jobson. thisiscolossal.com. May 9, 2014.