1987–88 South Pacific cyclone season

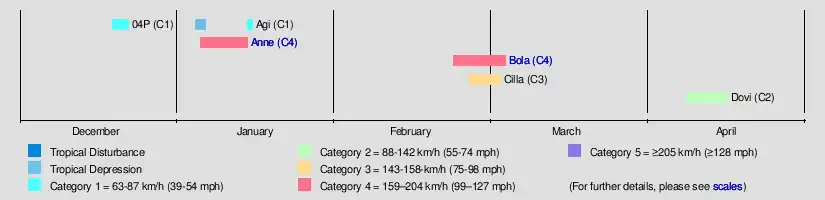

The 1987–88 South Pacific cyclone season was a quiet tropical cyclone season with five tropical cyclones and 2 severe tropical cyclones, observed within the South Pacific basin to the east of 160°E.

| 1987–88 South Pacific cyclone season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | December 1987 |

| Last system dissipated | April 16, 1988 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Anne |

| • Maximum winds | 185 km/h (115 mph) (10-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 925 hPa (mbar) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 6 |

| Tropical cyclones | 5 |

| Severe tropical cyclones | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 5 |

| Total damage | > $83 million (1987 USD) |

| Related articles | |

Seasonal summary

The 1987–88 season was a below-average tropical cyclone season with five named tropical cyclones, occurring within the South Pacific basin to the east of 160°E.[nb 1] The season was characterised by an El Niño event, which weakened and transitioned into a La Niña event, as the season progressed.[2][3] During the season tropical cyclones were officially monitored by the Fiji Meteorological Service and the New Zealand Meteorological Service, while the United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center and Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center also monitored the region.[4] During December 1987, the South Pacific Convergence Zone started to intensify as upper level westerly winds appeared near the equator, with two depressions forming near Tuvalu towards the end of December as a result.[5] Despite the low-level conditions being ideal for the development of a tropical cyclone at this stage, the surrounding upper-level conditions were unfavourable and the depressions dissipated while still in the low-latitudes.[5] Tropical Cyclone 04P was monitored near Tuvalu, by the JTWC and the NPMOC between December 18–22.[4][6] The system that was to become Tropical Cyclone Agi was first noted during January 3, while it was located about 740 km (460 mi) to the south-east of Honiara in the Solomon Islands.[7] Over the next few days the system moved south-westwards through the northern Vanuatu Islands, before it moved into the Australian Region during January 6.[2] The system was last noted during January 14, as it moved back into the basin as it interacted with Severe Tropical Cyclone Anne during that day.[2]

After the season had ended, the names Anne and Bola were retired from the list of South Pacific tropical cyclone names, while the name Agi was retired from the List of Australian region tropical cyclone names.[8]

Systems

Tropical Cyclone Agi

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 3 – January 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 km/h (40 mph) (10-min); 994 hPa (mbar) |

The system that was to become Tropical Cyclone Agi was first noted during January 3, while it was located about 740 km (460 mi) to the south-east of Honiara in the Solomon Islands.[7] Over the next few days the system moved south-westwards through the Northern Vanuatu Islands, before the JTWC initiated advisories on the system and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 06P during December 6.[4][7] The system subsequently moved into the Australian region, where it was named Agi by the Papua New Guinea National Weather Service during January 11.[2] After being named the system peaked as a Category 2 tropical cyclone, as it rapidly moved south-eastwards and started to interact with Severe Tropical Cyclone Anne.[2][7] The system moved back into the South Pacific basin during January 14, where it continued to weaken and posed a threat to New Caledonia.[2] The system was last noted later that day, as it merged with Anne near New Caledonia.[2][7] Overall the total damages from the system in Vanuatu, were estimated at US$500,000.[9]

Severe Tropical Cyclone Anne

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Category 5 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | January 5 – January 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 185 km/h (115 mph) (10-min); 925 hPa (mbar) |

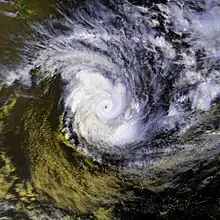

During January 5, a tropical depression developed about 540 km (335 mi) to the northeast of Funafuti, Tuvalu. [10] Over the next two days the system gradually developed further as it was steered towards the south — southwest, before it became equivalent to a tropical storm during January 7 while passing through the Tuvaluan Islands.[10][11] As a result, the JTWC designated the system as Tropical Cyclone 07P and started to issue advisories on it, before the FMS reported early on January 8, that the system had become equivalent to a modern-day category 2 tropical cyclone on the Australian Scale and named it Anne[4][10] As Anne continued to move south-westwards the cyclone's forward speed increased before it started to rapidly intensify during January 9, with the JTWC reporting during that day that the system had become equivalent to a category 1 hurricane on the SSHS.[10][11] Later that day, the FMS reported that the system had become equivalent to a category 3 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian Scale, before early the next day, Anne passed through the Santa Cruz Islands and about 55 km (35 mi) to the northwest of Anuta.[10]

Later on January 10, after it had become equivalent to a category 4 tropical cyclone on the SSHS, Anne directly passed over Vanuatu's Torres Islands and came within 65 km (40 mi) of Ureparapara in the Banks Islands.[10] Fortunately for the rest of Vanuatu though, Anne remained moving towards the south-westwards and only affected Northern Vanuatu.[10] Early on January 11, the FMS reported that Anne had peaked, with estimated 10-minute peak sustained winds near its center of 185 km/h (115 mph), which made it equivalent to a category 4 severe tropical cyclone on the Australian scale.[10] At around the same time the JTWC reported that Anne had peaked with 1-minute peak sustained winds near its center of 260 km/h (160 mph), which made it equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane on the SSHS.[11][12] Over the next day, as the cyclone turned towards the south, Cyclone Anne rapidly weakened as it encountered upper-level vertical windshear and approached New Caledonia.[10] Late on January 12, the FMS reported that Anne had weakened into a modern-day category 2 tropical cyclone, before it made landfall on New Caledonia about 110 km (70 mi) to the north — northwest of Nouméa.[10] After the cyclone had emerged into the Coral Sea, Anne continued to weaken, before it was last noted during January 14 by the FMS and the JTWC as it weakened into a depression and merged with Cyclone Agi.[4][10]

The system was responsible for severe and/or extensive damage within the Solomon Islands Temotu Province, Vanuatu and New Caledonia, while it caused minor damage to houses and cash crops when it moved through the central islands of Tuvalu. Within Temotu there was no official quantitative damage assessment and prompt relief measures were not carried out due to the lack of boats or aircraft and the remoteness of the islands.[13] Despite this Anuta, Utupua, the Duff Islands and the Reef Islands all reported extensive damage to property and crops.[13] Within Vanuatu, torrential rain, flooding and storm surge caused damage to houses, crops, and property with severe damage recorded on the islands of Ureparapara and the Torres Islands, while extensive damage was recorded on the islands of Vanua Lava and Gaua. Extensive damage was also reported on New Caledonia after it was exposed to a prolonged period of storm force winds, with the eastern and southern coasts particularly affected. The system produced the highest daily rainfall totals since 1951 in several areas on January 12. Two people were killed after they attempted to cross a flooded river during January 13, while about 80 others were injured by the cyclone.

Severe Tropical Cyclone Bola

| Category 4 severe tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Category 3 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 23 – March 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 165 km/h (105 mph) (10-min); 940 hPa (mbar) |

On February 24, the FMS started to monitor a tropical depression, that had developed within the South Pacific Convergence Zone to the north-northeast of Suva, Fiji.[14][15] During that day the system moved towards the southwest, before the JTWC initiated warnings on the system and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 13P.[4] Over the next 2 days the system gradually developed tropical cyclone characteristics as it moved south-westwards and passed to the northwest of Fiji.[14][16] Early on February 26, the FMS named the system Bola after it had become a category 1 tropical cyclone on the Australian scale.[17] The system initially moved south-westwards which seemed to indicate to the Vanuatu Meteorological Service, that the islands of Maewo and Pentecost were in some danger.[17] However, as Bola moved further southwards it entered a region of light and variable winds, which along with an area of high pressure in the Tasman Sea blocked Bola's movement southwards.[17] As a result, the systems future movement became hard to predict early on February 27 as it became slow moving.[17]

Severe Tropical Cyclone Cilla

| Category 3 severe tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | February 26 – March 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 km/h (75 mph) (10-min); 970 hPa (mbar) |

During the last week of February 1988, a shallow tropical depression developed within a trough of low pressure, between Aitutaki and Palmerston Island in the Southern Cook Islands.[18] Over the next couple of days the system moved south-eastwards and gradually developed further, before the NPMOC designated the system as Tropical Cyclone 15P and initiated advisories on the system during February 28.[4][19] During February 29, the depression was named Cilla, by the FMS after it had developed into a Category 1 tropical cyclone.[19][20] The system subsequently gradually developed further as it continued its south-eastwards movement and came to within 65 km (40 mi) of the Southern Cook Islands.[20] During March 1, the system briefly peaked as a Category 3 severe tropical cyclone, with 10-minute sustained wind speeds of 120 km/h (75 mph).[19][20] During that day, the NPMOC reported that the system had peaked with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 85 km/h (55 mph), which made it equivalent to a tropical storm.[4] Over the next few days, the system recurved southwards and moved into higher latitudes, before it dissipated during March 8.[19][20] The system had a minimal effect on land areas, with the French Polynesian islands of Rūrutu and Tupua'i affected by gale-force winds.[20]

Tropical Cyclone Dovi

| Category 2 tropical cyclone (Australian scale) | |

| Category 1 tropical cyclone (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 8 – April 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 km/h (70 mph) (10-min); 975 hPa (mbar) |

The final tropical cyclone of the season was first noted during April 8, as a tropical disturbance to the northeast of Vanuatu.[20][21] Over the next day the system moved south-eastwards towards Vanuatu and gradually developed gale-force winds near its centre, before the JTWC initiated advisories on the depression and designated it as Tropical Cyclone 19P.[4][20] The depression was subsequently named Dovi by the FMS during April 9, after it had become a Category 1 tropical cyclone and gale-force wind speeds had been confirmed by a report from Port Vila.[22][20] During the next day the system performed a small anti-clockwise cyclonic loop and started to intensify further while attaining a better cloud organization.[20] After it was named the system, slowly executed a double loop near Efate Island while intensifying further, before it restarted moving to the south-east during April 11.[21][23]

Dovi peaked as a category 2 tropical cyclone during April 12, with 10-minute sustained windspeeds of 110 km/h (70 mph), while the JTWC reported that the system had peaked with 1-minute sustained wind speeds of 130 km/h (80 mph), which made it equivalent to a category 1 hurricane on the SSHWS.[22][20] Over the next few days, Dovi gradually weakened gradually and became a depression during April 15, before the system was last noted to the south-east of Auckland, New Zealand during April 18.[22][20] Within Vanuatu, minor damages were reported on various islands including Tanna, which had suffered damage from Anne and Bola earlier in the season. As a result, it was noted by the Vanuatu Meteorological Service that such damage could have been missed.[24] Overall damages in Vanuatu were estimated at US$10,000, while there were no deaths reported as a result of Dovi.[9][24]

Seasonal effects

| Name | Dates active | Peak intensity | Areas affected | Damage (US$) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Wind speed | Pressure | ||||||

| Unnamed | December 19 – 22 | Tropical depression | Unknown | Unknown | Tuvalu | Minimal | None | [25] |

| Agi | January 4 – 14 | Category 1 tropical cyclone | 65 km/h (40 mph) | 997 hPa (29.44 inHg) | Vanuatu, New Caledonia | $500,000 | None | [7][9] |

| Anne | January 5 – 14 | Category 4 severe tropical cyclone | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | Tuvalu, Solomon Islands Vanuatu, New Caledonia | $500,000 | 2 | [9][26] |

| Bola | February 23 – March 4 | Category 4 severe tropical cyclone | 165 km/h (105 mph) | 940 hPa (27.76 inHg) | Fiji, Vanuatu, New Zealand | $82 million | 3 | [27] |

| Cilla | February 26 – march 3 | Category 3 severe tropical cyclone | 120 km/h (75 mph) | 970 hPa (28.64 inHg) | Cook Islands, French Polynesia | Minimal | None | [20] |

| Dovi | April 8 – 16 | Category 2 tropical cyclone | 110 km/h (70 mph) | 975 hPa (28.79 inHg) | Vanuatu | $10,000 | None | [9][24] |

| Season aggregates | ||||||||

| 6 systems | December 19, 1987 – April 16, 1988 | 185 km/h (115 mph) | 925 hPa (27.32 inHg) | $83 million | 5 | |||

Notes

- An average season between 1969–70 and 2014–15 contains 7.3 tropical cyclones.[1]

See also

References

- RSMC Nadi — Tropical Cyclone Centre (October 22, 2015). "2015–16 Tropical Cyclone Season Outlook in the Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre Nadi – Tropical Cyclone Centre (RSMC Nadi – TCC) Area of Responsibility (AOR)" (PDF). Fiji Meteorological Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Foley, G R. "The Australian Tropical Cyclone Season 1987-88" (PDF). Australian Meteorological Magazine (36): 205–212. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 21, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- "Cold & Warm Episodes by Season". www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- Annual Tropical Cyclone Report: 1988 (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1989. pp. 161–167. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2013. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Mariners Weather Log: Summer 1988 (Report). Vol. 32. United States National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. pp. 33–34. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094005. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- "Tropical Cyclone 04P Best Track Analysis". United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- "1988 Severe Tropical Cyclone Agi (1988003S12171)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- RA V Tropical Cyclone Committee (2023). Tropical Cyclone Operational Plan for the South-East Indian Ocean and the Southern Pacific Ocean 2023 (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- Report of the WMO Post-Tropical Cyclone "Pam" Expert Mission to Vanuatu (PDF) (Report). World Meteorological Organization. p. 22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-25. Retrieved 2015-12-24.

- Kishore, Satya; Fiji Meteorological Service (1988). DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Tropical Cyclone Anne (Mariners Weather Log: Volume 32: Issue 3: Summer 1988). United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. pp. 33–34. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094005. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886. Archived from the original on 2013-04-21. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center. "Tropical Cyclone 07P (Anne) best track analysis". United States Navy, United States Air Force. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center; Naval Pacific Meteorology and Oceanography Center. Chapter IV — Summary of South Pacific and South Indian Ocean Tropical Cyclones (PDF) (1988 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report). United States Navy, United States Air Force. pp. 160–167. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- Radford, Deirdre A; Blong, Russell J (1992). Natural Disasters in the Solomon Islands (PDF). Vol. 1 and 2 (2 ed.). The Australian International Development Assistance Bureau. pp. 125–126. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- Prasad, Rajendra; Fiji Meteorological Service (1988). DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Hurricane Alley: Tropical Cyclone Bola (Mariners Weather Log: Summer 1988). Vol. 32. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. pp. 34–36. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094005. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- Sinclair, Mark R (March 20, 1993). "A Diagnostic Study of the Extratropical Precipitation Resulting from Tropical Cyclone Bola". Monthly Weather Review. American Meteorological Society. 121 (10): 2690–2707. Bibcode:1993MWRv..121.2690S. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1993)121<2690:ADSOTE>2.0.CO;2.

- Barstow, Stephen F; Haug, Ola (1994). "Wave Climate of Fiji" (PDF). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

- Longworth, W. Mike (1988). Final report on Tropical cyclone Bola: 26 February - 4 March, 1988 (PDF) (Climatological Publication No. 23). Vanuatu Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-09. Retrieved 2014-04-06.

- Singh, Sudha; Kishore, Satya (August 25, 1988). Tropical Cyclone Report 88/4: Tropical Cyclone Cilla: February 28 - March 3, 1988 (Report). Fiji Meteorological Service.

- "1988 Tropical Cyclone Cilla (1988058S19198)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- DeAngellis, Richard M (ed.). Mariners Weather Log: Fall 1988 (Report). Vol. 32. United States National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. hdl:2027/uiug.30112104094013. ISSN 0025-3367. OCLC 648466886.

- Darwin Regional Specialised Meteorological Centre (1988). "April 1988" (PDF). Darwin Tropical Diagnostic Statement. 7 (4): 2–3. ISSN 1321-4233. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- "1988 Tropical Cyclone Dovi (1988100S15171)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- Barstow, Stephen F.; Haug, Ola. The Wave Climate of Vanuatu (PDF) (Technical Report 202). The South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. p. 17. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- Tropical cyclones in Vanuatu: 1847 to 1994 (PDF) (Report). Vanuatu Meteorological Service. May 19, 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2015.

- Barstow, Stephen F; Haug, Ola (November 1994). Wave Climate Of Tuvalu (PDF) (SOPAC Technical Report 203). South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 13, 2014. Retrieved April 12, 2014.

- New Caledonia Meteorological Office. "Phénomènes ayant le plus durement touché la Nouvelle-Calédonie: De 1880 à nos jours: Anne" [Phenomena having the hardest hit New Caledonia: From 1880 to the present: Anne]. Météo-France. Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- O'Loughlin, Colin L. (1991). "Priority Setting for Government Investment in Forestry Conservation Schemes — An Example from New Zealand" (PDF). USDA Forest Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

External links

- World Meteorological Organization

- Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- Fiji Meteorological Service

- New Zealand MetService

- Joint Typhoon Warning Center

- Trackmap of Severe Tropical Cyclone Anne from the Vanuatu Meteorological Service

- Trackmap of Severe Tropical Cyclone Bola from the Vanuatu Meteorological Service

- Trackmap of Tropical Cyclone Dovi from the Vanuatu Meteorological Service