Cyrtophora exanthematica

Cyrtophora exanthematica are tent spiders common in tropical Asia and Australia. They are commonly known as double-tailed tent spiders because of the pair of blunt projections at the end of their abdomens. They are harmless to humans.

| Double-tailed tent spider | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female Cyrtophora exanthematica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Order: | Araneae |

| Infraorder: | Araneomorphae |

| Family: | Araneidae |

| Genus: | Cyrtophora |

| Species: | C. exanthematica |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyrtophora exanthematica (Doleschall, 1859) | |

| |

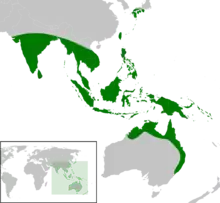

| C. exanthematica distribution map[1] | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

| |

Double-tailed tent spiders build large nonsticky webs of two parts – a tangle web and a finely-meshed horizontal orb web. The females of the species are larger than the males and they may vary considerably in colour. They are easily distinguishable by their shape, the markings on their backs, and the way the females have the habit of guarding their eggs by splaying their bodies over them.

Description

Their common name 'double-tailed tent spider' comes from the pair of blunt projections at the posterior end of their abdomens.[3] They are also known under other common names in Australia, including dome spider, bowl spider, pan-web spider, and scoop-web spider.[3][4][5]

Like other members of the genus Cyrtophora, the upper side of the cephalothorax of double-tailed tent spiders are flattened. The cephalothorax, the sides of the abdomen, and the legs are covered with white hairs. Its leg formula is I,II,III,IV – that is, the longest legs are the first pair at the front, the second pair the next longest, the third pair shorter than the second, and the last pair the shortest. The eight eyes are more or less of equal size and arranged in two recurved rows.[1]

They also possess the characteristic pair of humps on the front side of their abdomen, somewhat resembling 'shoulders' and giving them the distinctive triangular shape. On the upper side are eight prominent sigilla (small pit-like depressions) arranged in two rows. The abdomen is subrectangular, with somewhat flat sides, and has small tubercules at the front. It is longer than it is wide and tapers down towards the rear. The bottom side of the abdomen is usually brown with yellow book lungs. The spinnerets are rimmed with white. The epigynum in females possesses a short triangular scape (or ovipositor). The sperm receptacles (spermathecae) are globular.[1]

They can vary considerably in colour.[6] They can be red, pink, orange, yellow, brown, grey, pale brown, or completely black. In some individuals two somewhat wavy and sometimes 'beaded' chalk-white line patterns are clearly visible, running from the front of the abdomen, to the tip of the 'humps', and down to below its pair of 'tails'. In others, they are only present as faint lines.[7]

Double-tailed tent spiders are sexually dimorphic, with the males generally far smaller than the females.[1] Female adults average around 10 mm (0.39 in) in length (excluding the legs), but can reach up to 15 mm (0.59 in).[5] Male adults average only 3.5 to 6 mm (0.14 to 0.24 in), with the abdomen about the same size as the cephalothorax and with prominent pedipalps.[3][8]

Double-tailed tent spiders closely resemble Cyrtophora parangexanthematica in the Philippines. A fact reflected by its scientific name which literally means "like exanthematica" in Filipino.[1]

Taxonomy

Double-tailed tent spiders were first described by the Slovakian military surgeon Carl Ludwig Doleschall while stationed in Java in 1859 with the Dutch army.[9] He originally classified it under the genus Epeira (which is now the genus Araneus).[1] They are currently classified under the genus Cyrtophora (tent-web spiders) under subfamily Cyrtophorinae.[10] They belong to the very large orb-weaver spider family (Araneidae).[11]

The generic name Cyrtophora means "curve bearer", from Greek κυρτός ("kurtós", meaning 'bent' or 'curved') and φόρος ("phoros", meaning 'bearer' or 'carrying'), referring to the shape of the abdomen of the members of the genus.[5] The specific name "exanthematica" comes from the Greek ἐξάνθημα ("exanthema", meaning 'pimple') and the suffix -ικος ("-ikos", meaning 'pertaining to'), a reference to its appearance.[12]

Ecology

Double-tailed tent spiders usually build their webs in branches of trees or shrubs, using surrounding leaves and twigs as a framework. The webs are composed of two distinct parts. The upper section is an irregular dense mass of random supporting webs (known as a 'tangle web'). It serves to discourage prey from entering from the top of the web complex.[4] At the bottom is a horizontally-oriented, exceptionally finely-meshed web (the 'orb web') about 0.5 m (1.6 ft) in diameter.[13] Like those of other tent-web spiders, this web is somewhat tent-like. Unlike the others, however, the orb webs of double-tailed tent spiders are often shaped more like a pan or a bowl. No part of the web is sticky, unlike the webs of other orb-weavers.[1]

The spider stays in the middle of the lower orb web hanging upside down.[4] When it feels threatened, however, it will run to the edge of the web and hide among the vegetation and debris.[10] The spider has a sanctuary at the edge of the web surrounded by dead leaves which it can use to camouflage itself.[4] The male of the species can also inhabit the same web as the female.[10]

The webs are permanent. Over time, they will begin gathering leaves and other debris. Double-tailed tent spiders will regularly clean their webs, usually at night, though they will retain some bits and pieces of debris for camouflage. The webs sometimes have to be rebuilt when severely damaged.[10]

Double-tailed web spiders mate during summer. After mating, the female will lay her eggs in an egg sac (an ovoid ball of spider silk) in her sanctuary. She then stretches her body over the surface of the egg sac and guards it. This behavior is distinctive and makes the species easy to recognise.[8] The mother does not feed nor leave the sanctuary until the eggs have hatched, which is usually after two or three weeks. Only then will she return to the center of the web and resume her normal activities. The spiderlings will remain in her sanctuary for a few more weeks before setting out on their own.[4]

Because of the relatively large size of web, they are often infested with kleptoparasitic split-faced silver spiders (Argyrodes fissifrons).[13] While able to build webs of their own, dewdrop spiders (genus Argyrodes) prefer to live and even reproduce in the webs of other spiders, stealing prey in the process. They can be permanently associated with one web or move around between several other tent webs in the immediate vicinity. The size of the web is directly proportional to the number of A. fissifrons inhabiting them. The relationships can sometimes be commensal or even mutual, as A. fissifrons eat prey entangled in the webs that are too small for the larger double-tailed tent spiders. However, they often help themselves to food stores or even food in the process of being consumed by the hosts as well.[14] Larger individuals are more audacious, but they usually stay on the tangle webs and out of the way of their hosts. Double-tailed tent spiders seem to tolerate their presence though they sometimes have to shove them away when they catch larger prey.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Double-tailed tent spiders are widespread in tropical Asia and Australia. Their native range extends from Australia to southern Japan and from the Philippines and Papua New Guinea to as far west as India.[13] They usually build their permanent webs on the branches of trees or shrubs.[3][8]

Relations with humans

Like other tent-web spiders, double-tailed tent spiders are very shy. When threatened they will usually run away or play dead (also known as thanatosis). They are not aggressive to humans and they are unlikely to bite humans unless severely provoked. No bites have been recorded.[8]

The silk of double-tailed tent spiders are also among those being studied for possible applications in creating nanocapsules and microcapsules.[16]

See also

References

- A. T. Barrion; J. A. Litsinger (1995). Riceland spiders of South and Southeast Asia. CABI Publishing. International Rice Research Institute. p. 585. ISBN 978-0-85198-967-9.

- D. X. Song; J. X. Zhang; Daiqin Li (2002). "A Checklist of Spiders from Singapore (Arachnida – Araneae)" (PDF). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. National University of Singapore. 50 (2): 359–388. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- "Tent spiders: Cyrtophora moluccensis, Cyrtophora hirta, Cyrtophora exanthematica, family Araneidae". Queensland Museum. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Tony Chew; Sandy Chew; Peter Chew (28 November 2009). "Brisbane Spiders Field Guide". Brisbane Insects and Spiders. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Robert Doolan. "Bianca, the bowl spider". Critters of Calamvale Creek. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- "Cyrtophora exanthematica (Double Tailed Tent Spider)". Save Our Waterways Now. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Ramon Mascord (1980). Spiders of Australia: a field guide. Reed. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-589-50264-5.

- Ron Atkinson. "Cyrtophora exanthematica". The Find-A-Spider Guide for the Spiders of Southern Queensland. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- N. L. Evenhuis; David John Greathead (1999). "Collection Notes". World catalog of bee flies (Diptera: Bombyliidae) (PDF). Backhuys. p. 533. ISBN 978-90-5782-039-7.

- "Cyrtophorinae". Arachne.org.au. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- "Cyrtophora exanthematica (Doleschall, 1859)" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- "Etymology of the Latin word exanthema". MyEtymology. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Joseph K. H. Koh. "Double-Tailed Tent Spider: Cyrtophora exanthematica (Doleschall) 1859". A Guide to Common Singapore Spiders. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Joseph K. H. Koh. "Split-Faced Silver Spider: Argyrodes fissifrons Pickard-Cambridge 1869". A Guide to Common Singapore Spiders. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- I-Min Tso; Lucia Liu Severinghaus (2000). "Argyrodes fissifrons Inhabiting Webs of Cyrtophora Hosts: Prey Size Distribution and Population Characteristics" (PDF). Zoological Studies. Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica. 39 (3): 236–242. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Thomas Schelbel, Daniel Huemmerich, Andreas Bausch, & Kevin Hermanson (2010). Methods of Producing Nano- and Microcapsules of Spider Silk Proteins. U.S. Patent 11/989,907, filed August 1, 2006 and issued March 4, 2010.

External links

- Cyrtophora exanthematica Doleschall, 1859 Double Tailed Tent Spider at Arachne.org.au

- Pan-web Spider – Cyrtophora exanthematica at Brisbane Insects and Spiders

- Tent spiders at the Queensland Museum Official Website

- Cyrtophora exanthematica at the Find-a-spider Guide

- Riceland spiders of South and Southeast Asia by A. T. Barrion, J. A. Litsinger, and the International Rice Research Institute. A book freely available for non-commercial use under CC-BY-NC-SA.