Cynefin framework

The Cynefin framework (/kəˈnɛvɪn/ kuh-NEV-in)[1] is a conceptual framework used to aid decision-making.[2] Created in 1999 by Dave Snowden when he worked for IBM Global Services, it has been described as a "sense-making device".[3][4] Cynefin is a Welsh word for 'habitat'.[5]

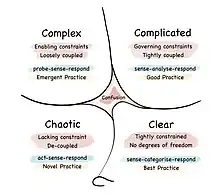

Cynefin offers five decision-making contexts or "domains"—clear (known as simple until 2014, then obvious until being recently renamed),[6] complicated, complex, chaotic, and confusion—that help managers to identify how they perceive situations and make sense of their own and other people's behaviour.[lower-alpha 1] The framework draws on research into systems theory, complexity theory, network theory and learning theories.[7]

Background

Terminology

The idea of the Cynefin framework is that it offers decision-makers a "sense of place" from which to view their perceptions.[8] Cynefin is a Welsh word meaning 'habitat', 'haunt', 'acquainted', 'familiar'. Snowden uses the term to refer to the idea that we all have connections, such as tribal, religious and geographical, of which we may not be aware.[9][5] It has been compared to the Māori word tūrangawaewae, meaning a place to stand, or the "ground and place which is your heritage and that you come from".[10]

History

Snowden, then of IBM Global Services, began work on a Cynefin model in 1999 to help manage intellectual capital within the company.[3][lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] He continued developing it as European director of IBM's Institute of Knowledge Management,[14] and later as founder and director of the IBM Cynefin Centre for Organizational Complexity, established in 2002.[15] Cynthia Kurtz, an IBM researcher, and Snowden described the framework in detail the following year in a paper, "The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world", published in IBM Systems Journal.[4][16][17]

The Cynefin Centre—a network of members and partners from industry, government and academia—began operating independently of IBM in 2004.[18] In 2007 Snowden and Mary E. Boone described the Cynefin framework in the Harvard Business Review.[2] Their paper, "A Leader's Framework for Decision Making", won them an "Outstanding Practitioner-Oriented Publication in OB" award from the Academy of Management's Organizational Behavior division.[19]

Domains

Cynefin offers five decision-making contexts or "domains": clear, complicated, complex, chaotic, and a centre of confusion.[lower-alpha 4] The domain names have changed over the years. Kurtz and Snowden (2003) called them known, knowable, complex, and chaotic.[4] Snowden and Boone (2007) changed known and knowable to simple and complicated.[lower-alpha 1] From 2014 Snowden used obvious in place of simple, and is now using the term clear[6]

The domains offer a "sense of place" from which to analyse behaviour and make decisions.[8] The domains on the right, clear and complicated, are "ordered": cause and effect are known or can be discovered. The domains on the left, complex and chaotic, are "unordered": cause and effect can be deduced only with hindsight or not at all.[20]

Clear

.jpeg.webp)

The clear domain represents the "known knowns". This means that there are rules in place (or best practice), the situation is stable, and the relationship between cause and effect is clear: if you do X, expect Y. The advice in such a situation is to "sense–categorize–respond": establish the facts ("sense"), categorize, then respond by following the rule or applying best practice. Snowden and Boone (2007) offer the example of loan-payment processing. An employee identifies the problem (for example, a borrower has paid less than required), categorizes it (reviews the loan documents), and responds (follows the terms of the loan).[2] According to Thomas A. Stewart,

This is the domain of legal structures, standard operating procedures, practices that are proven to work. Never draw to an inside straight. Never lend to a client whose monthly payments exceed 35 percent of gross income. Never end the meeting without asking for the sale. Here, decision-making lies squarely in the realm of reason: Find the proper rule and apply it.[21]

Snowden and Boone write that managers should beware of forcing situations into this domain by oversimplifying, by "entrained thinking" (being blind to new ways of thinking), or by becoming complacent. When success breeds complacency ("best practice is, by definition, past practice"), there can be a catastrophic clockwise shift into the chaotic domain. They recommend that leaders provide a communication channel, if necessary an anonymous one, so that dissenters (for example, within a workforce) can warn about complacency.[2]

Complicated

The complicated domain consists of the "known unknowns". The relationship between cause and effect requires analysis or expertise; there are a range of right answers. The framework recommends "sense–analyze–respond": assess the facts, analyze, and apply the appropriate good operating practice.[2] According to Stewart: "Here it is possible to work rationally toward a decision, but doing so requires refined judgment and expertise. ... This is the province of engineers, surgeons, intelligence analysts, lawyers, and other experts. Artificial intelligence copes well here: Deep Blue plays chess as if it were a complicated problem, looking at every possible sequence of moves."[21]

Complex

The complex domain represents the "unknown unknowns". Cause and effect can only be deduced in retrospect, and there are no right answers. "Instructive patterns ... can emerge," write Snowden and Boone, "if the leader conducts experiments that are safe to fail." Cynefin calls this process "probe–sense–respond".[2] Hard insurance cases are one example. "Hard cases ... need human underwriters," Stewart writes, "and the best all do the same thing: Dump the file and spread out the contents." Stewart identifies battlefields, markets, ecosystems and corporate cultures as complex systems that are "impervious to a reductionist, take-it-apart-and-see-how-it-works approach, because your very actions change the situation in unpredictable ways."[21]

Chaotic

In the chaotic domain, cause and effect are unclear.[lower-alpha 5] Events in this domain are "too confusing to wait for a knowledge-based response", writes Patrick Lambe. "Action—any action—is the first and only way to respond appropriately."[23] In this context, managers "act–sense–respond": act to establish order; sense where stability lies; respond to turn the chaotic into the complex.[2] Snowden and Boone write:

In the chaotic domain, a leader’s immediate job is not to discover patterns but to staunch the bleeding. A leader must first act to establish order, then sense where stability is present and from where it is absent, and then respond by working to transform the situation from chaos to complexity, where the identification of emerging patterns can both help prevent future crises and discern new opportunities. Communication of the most direct top-down or broadcast kind is imperative; there’s simply no time to ask for input.[2]

The September 11 attacks were an example of the chaotic category.[2] Stewart offers others: "the firefighter whose gut makes him turn left or the trader who instinctively sells when the news about the stock seems too good to be true." One crisis executive said of the collapse of Enron: "People were afraid. ... Decision-making was paralyzed. ... You've got to be quick and decisive—make little steps you know will succeed, so you can begin to tell a story that makes sense."[21]

Snowden and Boone give the example of the 1993 Brown's Chicken massacre in Palatine, Illinois—when robbers murdered seven employees in Brown's Chicken and Pasta restaurant—as a situation in which local police faced all the domains. Deputy Police Chief Walt Gasior had to act immediately to stem the early panic (chaotic), while keeping the department running (simple), calling in experts (complicated), and maintaining community confidence in the following weeks (complex).[2]

Confusion

The dark confusion domain in the centre represents situations where there is no clarity about which of the other domains apply (this domain has also been known as disordered in earlier versions of the framework). By definition it is hard to see when this domain applies. "Here, multiple perspectives jostle for prominence, factional leaders argue with one another, and cacophony rules", write Snowden and Boone. "The way out of this realm is to break down the situation into constituent parts and assign each to one of the other four realms. Leaders can then make decisions and intervene in contextually appropriate ways."[2]

Moving through domains

As knowledge increases, there is a "clockwise drift" from chaotic through complex and complicated to simple. Similarly, a "buildup of biases", complacency or lack of maintenance can cause a "catastrophic failure": a clockwise movement from simple to chaotic, represented by the "fold" between those domains. There can be counter-clockwise movement as people die and knowledge is forgotten, or as new generations question the rules; and a counter-clockwise push from chaotic to simple can occur when a lack of order causes rules to be imposed suddenly.[4][2]

Applications and reception

Cynefin was used by its IBM developers in policy-making, product development, market creation, supply chain management, branding and customer relations.[4] Later uses include analysing the impact of religion on policymaking within the George W. Bush administration,[25] emergency management,[26] network science and the military,[27] the management of food-chain risks,[28] homeland security in the United States,[29] agile software development,[30] and policing the Occupy Movement in the United States.[24]

It has also been used in health-care research, including to examine the complexity of care in the British National Health Service,[31] the nature of knowledge in health care,[32] and the fight against HIV/AIDS in South Africa.[33] In 2017 the RAND Corporation used the Cynefin framework in a discussion of theories and models of decision making.[34] The European Commission has published a field guide to use Cynefin as a "guide to navigate crisis".[35]

Criticism of Cynefin includes that the framework is difficult and confusing, needs a more rigorous foundation, and covers too limited a selection of possible contexts.[36] Another criticism is that terms such as known, knowable, sense, and categorize are ambiguous.[37]

Prof Simon French recognizes "the value of the Cynefin framework in categorising decision contexts and identifying how to address many uncertainties in an analysis" and as such believes it builds on seminal works such as Russell L. Ackoff's Scientific Method: optimizing applied research decisions (1962), C. West Churchman's Inquiring Systems (1967), Rittel and Webber's Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning (1973), Douglas John White's Decision Methodology (1975), John Tukey's Exploratory data analysis (1977), Mike Pidd's Tools for Thinking: Modelling in Management Science (1996), and Ritchey's General Morphological Analysis (1998).[38]

Cynefin and theory of constraints

Steve Holt compares Cynefin to the theory of constraints. The theory of constraints argues that most systems outcomes are limited by certain bottlenecks (constraints) and improvements away from these constraints tend to be counterproductive because they just place more strain on a constraint. Holt places the theory of constraints within the Cynefin framing by arguing the theory of constraints moves from complex situations to complicated ones by using abductive reasoning and intuition then logic to creating an understanding, before creating a probe to test understanding.[39]: 367

Cynefin defines several types of constraints. Fixed constraints stipulate that actions must be done in a certain way in a certain order and apply in the clear domain, governing constraints are looser and act more like rules or policies applying in the complicated domain, enabling constraints that operate in the complex domain are constraints that allow a system to function but do not control the entire process.[39]: 371 Holt argues that constraints in the theory of constraints correspond the Cynefin's fixed and governing constraints. Holt argues that injections in the theory of constraints correspond to enabling constraints.[39]: 373

Critiques

Firestone and McElroy argue that Cynefin is a model of sensemaking rather than a full model of knowledge management and processing.[40]: 118

See also

Notes

- Snowden and Boone (2007): "The framework sorts the issues facing leaders into five contexts defined by the nature of the relationship between cause and effect. Four of these—simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic—require leaders to diagnose situations and to act in contextually appropriate ways. The fifth—disorder—applies when it is unclear which of the other four contexts is predominant."[2]

- Snowden (2000): "An early form of the Cynefin model using different labels for the dimension extremes and quadrant spaces was developed as a means of understanding the reality of intellectual capital management within IBM Global Services (Snowden 1999a)."[11][12]

- Snowden, Pauleen, and Jansen van Vuuren (2011): "The framework was initially used in Snowden's early work in knowledge management, but now extends to aspects of leadership, strategy, cultural change, customer relationship management and more (Kurtz and Snowden 2003; Snowden and Boone 2007). The framework is particularly effective in helping decision-makers to make sense of complex problems, providing new ways of approaching intractable problems and allowing the emergence of shared understandings from collective groups."[13]

- Williams and Hummelbrunner (2010): " ... Cynefin identifies four behaviors a situation can display: simple, complicated, complex, and chaotic. This terminology is not new; the systems literature has used it for decades. However, in Cynefin the behaviors and the properties that underpin these four states are not entirely drawn from systems theories or even theories of chaos and complexity. Cynefin draws heavily on network theory, learning theories, and third-generation knowledgement management."Crucially, compared with many network and company approaches, Cynefin also takes an epistemological as well as an ontological stance. Similar to the Soft Systems and Critical Systems traditions ... Cynefin explores how people perceive and learn from situations."[16]

- Cynefin uses chaotic in the ordinary sense, rather than in the sense used in chaos theory.[22]

References

- CognitiveEdge (11 July 2010), The Cynefin Framework, archived from the original on 19 December 2021, retrieved 6 March 2019

- Snowden, David J.; Boone, Mary E. (2007). "A Leader's Framework for Decision Making". Harvard Business Review. 85 (11): 68–76. PMID 18159787.

- Snowden, David (1999). "Liberating Knowledge", in Liberating Knowledge. CBI Business Guide. London: Caspian Publishing.

- Kurtz, Cynthia F.; Snowden, David J. (2003). "The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world" (PDF). IBM Systems Journal. 42 (3): 462–483. doi:10.1147/sj.423.0462. S2CID 1571304. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2006.

- Berger, Jennifer Harvey; Johnston, Keith (2015). Simple Habits for Complex Times. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. 236–237, n. 5. "Cynefin". Welsh-English / English-Welsh On-line Dictionary. University of Wales. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- Berger & Johnston (2015), 237, n. 7.

- Williams, Bob; Hummelbrunner, Richard (2010). Systems Concepts in Action: A Practitioner's Toolkit. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. pp. 10, 163–164.

- Browning, Larry; Latoza, Roderick (31 December 2005). "The use of narrative to understand and respond to complexity: A comparative analysis of the Cynefin and Weickian models", Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 7(3–4): 32–39 (last modified: 23 November 2016).

- "Honorary Professorship for David J Snowden". Bangor University School of Psychology. 15 April 2015.

- Berger & Johnston (2015), 236–237, n. 5.

- Snowden, Dave (2000). "The Social Ecology of Knowledge Management". In Despres, Charles; Chauvel, Daniele (eds.). Knowledge Horizons. Boston: Butterworth–Heinemann. 239.

- Also see Snowden, Dave. "Cynefin, A Sense of Time and Place: an Ecological Approach to Sense Making and Learning in Formal and Informal Communities". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu.

- Snowden, Dave; Pauleen, David J.; Jansen van Vuuren, Sally (2016). "Knowledge Management and the Individual: It's Nothing Personal", in David J. Pauleen and Gorman, G. E. (eds.). Personal Knowledge Management. Abingdon: Routledge 2011, 116.

- Snowden 2000, 237–266; Snowden, Dave (2002). "Complex Acts of Knowing: Paradox and Descriptive Self Awareness" (PDF). Journal of Knowledge Management. 6 (2): 100–111. doi:10.1108/13673270210424639. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2003.

- Kurtz and Snowden (2003), 483; "The Cynefin Centre for Organisational Complexity", IBM, archived 14 June 2002; "Membership", IBM, archived 10 August 2002.

- Williams & Hummelbrunner 2010, 10, 163–164.

- Quiggin, Thomas (2007). "Interview with Mr. Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge", Seeing the Invisible: National Security Intelligence in an Uncertain Age. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co., 212.

- "The Cynefin Centre: Life after IBM", KM World, 14(7), July/August 2005.

- "Outstanding Practitioner-Oriented Publication in OB", obweb.org.

- Koskela, Lauri; Kagioglou, Mike (2006). "On the Metaphysics of Production" Archived 23 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Proceedings of the 13th Annual Conference on Lean Construction, Sydney, Australia, July 2005 (37–45), 42–43.

- Stewart, Thomas A. (November 2002). "How to Think With Your Gut". Business 2.0. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original on 5 November 2002. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- Berger & Johnston (2015), 237, n. 11.

- Lambe, Patrick (2007). Organising Knowledge: Taxonomies, Knowledge and Organisational Effectiveness. Oxford: Chandos Publishing, 136.

- Geron, Stephen Max (March 2014). "21st Century strategies for policing protest" (pdf), Naval Postgraduate School.

- O'Neill, Louisa-Jayne (2004). "Faith and decision-making in the Bush presidency: The God elephant in the middle of America's livingroom" (PDF). Emergence: Complexity and Organisation. 6 (1/2): 149–156. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2011.

- French, Simon; Niculae, Carmen (March 2005). "Believe in the Model: Mishandle the Emergency". Journal of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. 2 (1). doi:10.2202/1547-7355.1108. S2CID 110745815.

- Verdon, John (July 2005). "Transformation in the CF: Concept towards a theory of Human Network-Enabled". Ottawa: National Defence, Directory of Strategic Human Resources.

- Shepherd, Richard; Barker, Gary; French, Simon; et al. (July 2006). "Managing Food Chain Risks: Integrating Technical and Stakeholder Perspectives on Uncertainty". Journal of Agricultural Economics. 57 (2): 313–327. doi:10.1111/j.1477-9552.2006.00054.x.

- Bellavita, Christopher (2006). "Shape Patterns, Not Programs". Homeland Security Affairs. II (3): 1–21.

- Pelrine, Joseph (March 2011). "On Understanding Software Agility: A Social Complexity Point Of View" (PDF). Emergence: Complexity & Organization. 13 (1/2): 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Mark, Annabelle L. (2006). "Notes from a Small Island: Researching Organisational Behaviour in Healthcare from a UK Perspective". Journal of Organizational Behavior. 27 (7): 851–867. doi:10.1002/job.414. JSTOR 4093874.

- Sturmberg, Joachim P.; Martin, Carmel M. (October 2008). "Knowing – in Medicine". Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 14 (5): 767–770. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01011.x. PMID 19018908.

- Burman, Christopher J.; Aphane, Marota A. (2016). "Leadership emergence: the application of the Cynefin framework during a bio-social HIV/AIDS risk-reduction pilot". African Journal of AIDS Research. 15 (3): 249–260. doi:10.2989/16085906.2016.1198821. PMID 27681149. S2CID 27834963.

- Cox, Kate; Strang, Lucy; Sondergaard, Susan; and Monsalve, Cristina Gonzalez (2017). "Understanding how organisations ensure that their decision making is fair". Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- "JRC Publications Repository". publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- Firestone, Joseph M.; McElroy, Mark W. (2011). Key Issues in the New Knowledge Management. Abingdon: Routledge, 132–133 (first published 2003).

- Williams & Hummelbrunner 2010, 182.

- French, Simon (2017). "Cynefin: uncertainty, small worlds and scenarios". Journal of the Operational Research Society. 66 (10): 1635–1645. doi:10.1057/jors.2015.21. S2CID 16750919.

- Cynefin weaving sense-making into the fabric of our world. Dave Snowden, Riva Greenberg, Boudewijn Bertsch. Cognitive Edge - The Cynefin Co. 2021. ISBN 978-1-7353799-0-6. OCLC 1226544685.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - Firestone, Joseph M. (2003). Key issues in the new knowledge management. Mark W. McElroy. [Hartland Four Corners, Vt]: KMCI Press. ISBN 0-7506-7655-8. OCLC 51861908.