Cystathionine beta synthase

Cystathionine-β-synthase, also known as CBS, is an enzyme (EC 4.2.1.22) that in humans is encoded by the CBS gene. It catalyzes the first step of the transsulfuration pathway, from homocysteine to cystathionine:[5]

CBS uses the cofactor pyridoxal-phosphate (PLP) and can be allosterically regulated by effectors such as the ubiquitous cofactor S-adenosyl-L-methionine (adoMet). This enzyme belongs to the family of lyases, to be specific, the hydro-lyases, which cleave carbon-oxygen bonds.

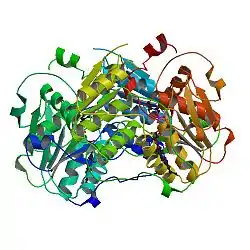

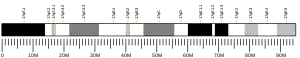

CBS is a multidomain enzyme composed of an N-terminal enzymatic domain and two CBS domains. The CBS gene is the most common locus for mutations associated with homocystinuria.[6]

Nomenclature

The systematic name of this enzyme class is L-serine hydro-lyase (adding homocysteine; L-cystathionine-forming). Other names in common use include:

- β-thionase,

- cysteine synthase,

- L-serine hydro-lyase (adding homocysteine),

- methylcysteine synthase,

- serine sulfhydrase, and

- serine sulfhydrylase.

Methylcysteine synthase was assigned the EC number EC 4.2.1.23 in 1961. A side-reaction of CBS caused this. The EC number EC 4.2.1.23 was deleted in 1972.[7]

Structure

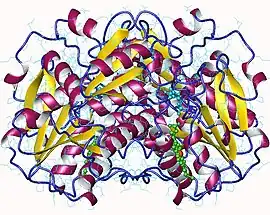

The human enzyme cystathionine β-synthase is a tetramer and comprises 551 amino acids with a subunit molecular weight of 61 kDa. It displays a modular organization of three modules with the N-terminal heme domain followed by a core that contains the PLP cofactor.[9] The cofactor is deep in the heme domain and is linked by a Schiff base.[10] A Schiff base is a functional group containing a C=N bond with the nitrogen atom connected to an aryl or alkyl group. The heme domain is composed of 70 amino acids and it appears that the heme only exists in mammalian CBS and is absent in yeast and protozoan CBS. At the C-terminus, the regulatory domain of CBS contains a tandem repeat of two CBS domains of β-α-β-β-α, a secondary structure motif found in other proteins.[9] CBS has a C-terminal inhibitory domain. The C-terminal domain of cystathionine β-synthase regulates its activity via both intrasteric and allosteric effects and is important for maintaining the tetrameric state of the protein.[9] This inhibition is alleviated by binding of the allosteric effector, adoMet, or by deletion of the regulatory domain; however, the magnitude of the effects differ.[9] Mutations in this domain are correlated with hereditary diseases.[11]

The heme domain contains an N-terminal loop that binds heme and provides the axial ligands C52 and H65. The distance of heme from the PLP binding site suggests its non-role in catalysis, however deletion of the heme domain causes loss of redox sensitivity, therefore it is hypothesized that heme is a redox sensor.[10] The presence of protoporphyrin IX in CBS is a unique PLP-dependent enzyme and is only found in the mammalian CBS. D. melanogaster and D. discoides have truncated N-terminal extensions and therefore prevent the conserved histidine and cysteine heme ligand residues. However, the Anopheles gambiae sequence has a longer N-terminal extension than the human enzyme and contains the conserved histidine and cysteine heme ligand residues like the human heme. Therefore, it is possible that CBS in slime molds and insects are hemeproteins that suggest that the heme domain is an early evolutionary innovation that arose before the separation of animals and the slime molds.[9] The PLP is an internal aldimine and forms a Schiff base with K119 in the active site. Between the catalytic and regulatory domains exists a hypersensitive site that causes proteolytic cleavage and produces a truncated dimeric enzyme that is more active than the original enzyme. Both truncated enzyme and the enzyme found in yeast are not regulated by adoMet. The yeast enzyme is also activated by the deletion of the C-terminal to produce the dimeric enzyme.[9]

As of late 2007, two structures have been solved for this class of enzymes, with PDB accession codes 1JBQ and 1M54.

Enzymatic activity

| cystathionine beta-synthase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cystathionine beta synthase homodimer, Human | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| EC no. | 4.2.1.22 | ||||||||

| CAS no. | 9023-99-8 | ||||||||

| Databases | |||||||||

| IntEnz | IntEnz view | ||||||||

| BRENDA | BRENDA entry | ||||||||

| ExPASy | NiceZyme view | ||||||||

| KEGG | KEGG entry | ||||||||

| MetaCyc | metabolic pathway | ||||||||

| PRIAM | profile | ||||||||

| PDB structures | RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum | ||||||||

| Gene Ontology | AmiGO / QuickGO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Transsulfuration, catalyzed by CBS, converts homocysteine to cystathionine, which cystathione gamma lyase converts to cysteine.[12]

CBS occupies a pivotal position in mammalian sulfur metabolism at the homocysteine junction where the decision to conserve methionine or to convert it to cysteine via the transsulfuration pathway, is made. Moreover, the transsulfuration pathway is the only pathway capable of removing sulfur-containing amino acids under conditions of excess.[9]

In analogy with other β-replacement enzymes, the reaction catalyzed by CBS is predicted to involve a series of adoMet-bound intermediates. Addition of serine results in a transchiffization reaction, which forms of an external aldimine. The aldimine undergoes proton abstraction at the α-carbon followed by elimination to generate an amino-acrylate intermediate. Nucleophilic attack by the thiolate of homocysteine on the aminoacrylate and reprotonation at Cα generate the external aldimine of cystathionine. A final transaldimination reaction releases the final product, cystathionine.[9] The final product, L-cystathionine can also form an aminoacrylate intermediate, indicating that the entire reaction of CBS is reversible.[13]

The measured V0 of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction, in general, reflects the steady state (where [ES] is constant), even though V0 is limited to the early part of a reaction, and analysis of these initial rates is referred to as steady-state kinetics. Steady-state kinetic analysis of yeast CBS yields parallel lines. These results agree with the proposed ping-pong mechanism in which serine binding and release of water are followed by homocysteine binding and release of cystathionine. In contrast, the steady-state enzyme kinetics of rat CBS yields intersecting lines, indicating that the β-substituent of serine is not released from the enzyme prior to binding of homocysteine.[9]

One of the alternate reactions involving CBS is the condensation of cysteine with homocysteine to form cystathionine and hydrogen sulfide (H2S).[13] H2S in the brain is produced from L-cysteine by CBS. This alternative metabolic pathway is also dependent on adoMet.[14]

CBS enzyme activity is not found in all tissues and cells. It is absent from heart, lung, testes, adrenal, and spleen in rats. In humans, it has been shown to be absent in heart muscle and primary cultures of human aortic endothelial cells. The lack of CBS in these tissues implies that these tissues are unable to synthesize cysteine and that cysteine must be supplied from extracellular sources. It also suggests that these tissues might have increased sensitivity to homocysteine toxicity because they cannot catabolize excess homocysteine via transsulfuration.[13]

Regulation

Allosteric activation of CBS by adoMet determines the metabolic fate of homocysteine. Mammalian CBS is activated 2.5-5-fold by AdoMet with a dissociation constant of 15 μM.[6] AdoMet is an allosteric activator that increases the Vmax of the CBS reaction but does not affect the Km for the substrates. In other words, AdoMet stimulates CBS activity by increasing the turnover rate rather than the binding of substrates to the enzyme.[9] This protein may use the morpheein model of allosteric regulation.[15]

Human CBS performs a crucial step in the biosynthetic pathway of cysteine by providing a regulatory control point for AdoMet. Homocysteine, after being methylated to methionine, can be converted to AdoMet, which donates methyl groups to a variety of substrates, e.g., neurotransmitters, proteins, and nucleic acids. AdoMet functions as an allosteric activator of CBS and exerts control on its biosynthesis: low concentrations of AdoMet result in low CBS activity, thereby funneling homocysteine into the transmethylation cycle toward AdoMet formation. In contrast, high adoMet concentrations funnel homocysteine into the transsulfuration pathway toward cysteine biosynthesis.[16]

In mammals, CBS is a highly regulated enzyme, which contains a heme cofactor that functions as a redox sensor,[11] that can modulate its activity in response to changes in the redox potential. If the resting form of CBS in the cell has ferrous (Fe2+) heme, the potential exists for activating the enzyme under oxidizing conditions by conversion to the ferric (Fe3+) state.[9] The Fe2+ form of the enzyme is inhibited upon binding CO or nitric oxide, whereas enzyme activity is doubled when the Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+. The redox state of the heme is pH dependent, with oxidation of Fe2+–CBS to Fe3+–CBS being favored at low pH conditions.[17]

Since mammalian CBS contains a heme cofactor, whereas yeast and protozoan enzyme from Trypanosoma cruzi do not have heme cofactors, researchers have speculated that heme is not required for CBS activity.[9]

CBS is regulated at the transcriptional level by NF-Y, SP-1, and SP-3. In addition it is upregulated transcriptionally by glucocorticoids and glycogen, and downregulated by insulin. Methionine upregulates CBS at the post-transcriptional level.

Human disease

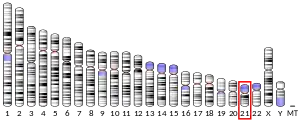

Down syndrome is a medical condition characterized by an overexpression of cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and a low level of homocysteine in the blood. It has been speculated that cystathionine beta synthase overexpression could be the major culprit in this disease (along with dysfunctioning of GabaA and Dyrk1a). The phenotype of down syndrome is the opposite of Hyperhomocysteinemia (described below). Pharmacologicals inhibitors of CBS have been patented by the Jerome Lejeune Foundation (November 2011) and trials (animals and humans are planned).

Hyperhomocysteinemia is a medical condition characterized by an abnormally large level of homocysteine in the blood. Mutations in CBS are the single most common cause of hereditary hyperhomocysteinemia. Genetic defects that affect the MTHFR, MTR, and MTRR/MS enzyme pathways can also contribute to high homocysteine levels. Inborn errors in CBS result in hyperhomocysteinemia with complications in the cardiovascular system leading to early and aggressive arterial disease. Hyperhomocysteinemia also affects three other major organ systems including the ocular, central nervous, and skeletal.[9]

Homocystinuria due to CBS deficiency is a special type of hyperhomocysteinemia. It is a rare, hereditary recessive autosomal disease, in general diagnosed during childhood. A total of 131 different homocystinuria-causing mutations have been identified. A common functional feature of the mutations in the CBS domains is that the mutations abolish or strongly reduce activation by adoMet.[16] No specific cure has been discovered for homocystinuria; however, many people are treated using high doses of vitamin B6, which is a cofactor of CBS.

Bioengineering

Cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) is involved in oocyte development. However, little is known about the regional and cellular expression patterns of CBS in the ovary and research is now focused on determining the location and expression during follicle development in the ovaries.[18]

Absence of Cystathionine beta synthase in mice provokes infertility due to the loss of uterine protein expression.[19]

Mutations

The genes that control CBS enzyme expression may not operate at 100% efficiency in individuals who have one of the SNPs (single-nucleotide polymorphisms, a type of mutations) that affect this gene. Known variants include the A360A, C699T, I278T, N212N, and T42N SNPs (among others). These SNPs, which have varied effects on the effectiveness of the enzyme, can be detected with standard DNA testing methods.

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000160200 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024039 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Entrez Gene: CBS cystathionine-beta-synthase".

- Janosík M, Kery V, Gaustadnes M, Maclean KN, Kraus JP (September 2001). "Regulation of human cystathionine beta-synthase by S-adenosyl-L-methionine: evidence for two catalytically active conformations involving an autoinhibitory domain in the C-terminal region". Biochemistry. 40 (35): 10625–33. doi:10.1021/bi010711p. PMID 11524006.

- EC 4.2.1.23

- PDB: 1JBQ; Meier M, Janosik M, Kery V, Kraus JP, Burkhard P (August 2001). "Structure of human cystathionine beta-synthase: a unique pyridoxal 5'-phosphate-dependent heme protein". The EMBO Journal. 20 (15): 3910–6. doi:10.1093/emboj/20.15.3910. PMC 149156. PMID 11483494.

- Banerjee R, Zou CG (January 2005). "Redox regulation and reaction mechanism of human cystathionine-beta-synthase: a PLP-dependent hemesensor protein". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 433 (1): 144–56. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.08.037. PMID 15581573.

- Yamanishi M, Kabil O, Sen S, Banerjee R (December 2006). "Structural insights into pathogenic mutations in heme-dependent cystathionine-beta-synthase". Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 100 (12): 1988–95. doi:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2006.08.020. PMID 17069888.

- Kabil O, Zhou Y, Banerjee R (November 2006). "Human cystathionine beta-synthase is a target for sumoylation". Biochemistry. 45 (45): 13528–36. doi:10.1021/bi0615644. PMID 17087506.

- Nozaki T, Shigeta Y, Saito-Nakano Y, Imada M, Kruger WD (March 2001). "Characterization of transsulfuration and cysteine biosynthetic pathways in the protozoan hemoflagellate, Trypanosoma cruzi. Isolation and molecular characterization of cystathionine beta-synthase and serine acetyltransferase from Trypanosoma". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (9): 6516–23. doi:10.1074/jbc.M009774200. PMID 11106665.

- Jhee KH, Kruger WD (2005). "The role of cystathionine beta-synthase in homocysteine metabolism". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 7 (5–6): 813–22. doi:10.1089/ars.2005.7.813. PMID 15890029.

- Eto K, Kimura H (November 2002). "A novel enhancing mechanism for hydrogen sulfide-producing activity of cystathionine beta-synthase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (45): 42680–5. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205835200. PMID 12213817.

- T. Selwood & E. K. Jaffe (2011). "Dynamic dissociating homo-oligomers and the control of protein function". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 519 (2): 131–43. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2011.11.020. PMC 3298769. PMID 22182754.

- Ignoul S, Eggermont J (December 2005). "CBS domains: structure, function, and pathology in human proteins". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 289 (6): C1369–78. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00282.2005. PMID 16275737.

- Puranik M, Weeks CL, Lahaye D, Kabil O, Taoka S, Nielsen SB, Groves JT, Banerjee R, Spiro TG (May 2006). "Dynamics of carbon monoxide binding to cystathionine beta-synthase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (19): 13433–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M600246200. PMC 2745537. PMID 16505479.

- Liang R, Yu WD, Du JB, Yang LJ, Shang M, Guo JZ (November 2006). "Localization of cystathionine beta synthase in mice ovaries and its expression profile during follicular development". Chinese Medical Journal. 119 (22): 1877–83. doi:10.1097/00029330-200611020-00006. PMID 17134586. S2CID 23891500.

- Guzmán MA, Navarro MA, Carnicer R, Sarría AJ, Acín S, Arnal C, Muniesa P, Surra JC, Arbonés-Mainar JM, Maeda N, Osada J (November 2006). "Cystathionine beta-synthase is essential for female reproductive function". Human Molecular Genetics. 15 (21): 3168–76. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl393. PMID 16984962.

Further reading

- Kraus JP (1994). "Komrower Lecture. Molecular basis of phenotype expression in homocystinuria". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 17 (4): 383–90. doi:10.1007/BF00711354. PMID 7967489. S2CID 42317828.

- Kraus JP, Janosík M, Kozich V, et al. (1999). "Cystathionine beta-synthase mutations in homocystinuria". Hum. Mutat. 13 (5): 362–75. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:5<362::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 10338090. S2CID 86447340.

- Jones AL (1999). "The localization and interactions of huntingtin". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 354 (1386): 1021–7. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0454. PMC 1692601. PMID 10434301.

- Griffiths R, Tudball N (1977). "The molecular defect in a case of (cystathionine beta-synthase)-deficient homocystinuria". Eur. J. Biochem. 74 (2): 269–73. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11390.x. PMID 404147.

- Kraus J, Packman S, Fowler B, Rosenberg LE (1978). "Purification and properties of cystathionine beta-synthase from human liver. Evidence for identical subunits". J. Biol. Chem. 253 (18): 6523–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)46963-9. PMID 681363.

- Longhi RC, Fleisher LD, Tallan HH, Gaull GE (1977). "Cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: a qualitative abnormality of the deficient enzyme modified by vitamin B6 therapy". Pediatr. Res. 11 (2): 100–3. doi:10.1203/00006450-197702000-00003. PMID 840498.

- Kozich V, Kraus JP (1993). "Screening for mutations by expressing patient cDNA segments in E. coli: homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency". Hum. Mutat. 1 (2): 113–23. doi:10.1002/humu.1380010206. PMID 1301198. S2CID 36663527.

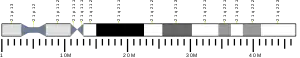

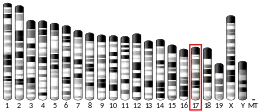

- Münke M, Kraus JP, Ohura T, Francke U (1988). "The gene for cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) maps to the subtelomeric region on human chromosome 21q and to proximal mouse chromosome 17". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 42 (4): 550–9. PMC 1715237. PMID 2894761.

- Hu FL, Gu Z, Kozich V, et al. (1994). "Molecular basis of cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in pyridoxine responsive and nonresponsive homocystinuria". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (11): 1857–60. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.11.1857. PMID 7506602.

- Sperandeo MP, Panico M, Pepe A, et al. (1995). "Molecular analysis of patients affected by homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency: report of a new mutation in exon 8 and a deletion in intron 11". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 18 (2): 211–4. doi:10.1007/BF00711769. PMID 7564249. S2CID 40407615.

- Chassé JF, Paly E, Paris D, et al. (1995). "Genomic organization of the human cystathionine beta-synthase gene: evidence for various cDNAs". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211 (3): 826–32. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.1886. PMID 7598711.

- Shih VE, Fringer JM, Mandell R, et al. (1995). "A missense mutation (I278T) in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene prevalent in pyridoxine-responsive homocystinuria and associated with mild clinical phenotype". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 57 (1): 34–9. PMC 1801250. PMID 7611293.

- Kluijtmans LA, Blom HJ, Boers GH, et al. (1995). "Two novel missense mutations in the cystathionine beta-synthase gene in homocystinuric patients". Hum. Genet. 96 (2): 249–50. doi:10.1007/BF00207394. PMID 7635485. S2CID 6642338.

- Sebastio G, Sperandeo MP, Panico M, et al. (1995). "The molecular basis of homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency in Italian families, and report of four novel mutations". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 56 (6): 1324–33. PMC 1801112. PMID 7762555.

- Marble M, Geraghty MT, de Franchis R, et al. (1995). "Characterization of a cystathionine beta-synthase allele with three mutations in cis in a patient with B6 nonresponsive homocystinuria". Hum. Mol. Genet. 3 (10): 1883–6. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.10.1883. PMID 7849717.

- Kraus JP, Le K, Swaroop M, et al. (1994). "Human cystathionine beta-synthase cDNA: sequence, alternative splicing and expression in cultured cells". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (10): 1633–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.10.1633. PMID 7903580.

- de Franchis R, Kozich V, McInnes RR, Kraus JP (1995). "Identical genotypes in siblings with different homocystinuric phenotypes: identification of three mutations in cystathionine beta-synthase using an improved bacterial expression system". Hum. Mol. Genet. 3 (7): 1103–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.7.1103. PMID 7981678.

- Kruger WD, Cox DR (1994). "A yeast system for expression of human cystathionine beta-synthase: structural and functional conservation of the human and yeast genes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91 (14): 6614–8. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.6614K. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.14.6614. PMC 44253. PMID 8022826.

- Kozich V, de Franchis R, Kraus JP (1993). "Molecular defect in a patient with pyridoxine-responsive homocystinuria". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (6): 815–6. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.6.815. PMID 8353501.