Tasmanian emu

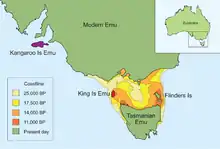

The Tasmanian emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis) is an extinct subspecies of emu. It was found in Tasmania, where it had become isolated during the Late Pleistocene. As opposed to the other insular emu taxa, the King Island emu and the Kangaroo Island emu, the population on Tasmania was sizable, meaning that there were no marked effects of small population size as in the other two isolates.

| Tasmanian emu | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1910 restoration by John Gerrard Keulemans, based on a skin at the British Museum, posed after a photograph of the mainland emu | |

Extinct (1865) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae |

| Order: | Casuariiformes |

| Family: | Casuariidae |

| Genus: | Dromaius |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †D. n. diemenensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| †Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis Le Souef, 1907 | |

| |

| Geographic distribution of emu taxa and historic shoreline reconstructions around Tasmania | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dromaeius diemenensis (lapsus) Le Souef, 1907 | |

The Tasmanian emu became extinct around 1865 according to the Australian Species Profile and Threats database.[1] This was officially recorded in 1997 when changes to listings of nationally threatened species saw the Tasmanian emu added to the list of species presumed extinct.[2]

Information regarding the emu is reliant on 19th century documentary evidence and the limited number of emu specimens in museums. As a consequence one of the biggest challenges in researching the Tasmanian emu is the many names or spellings used to describe the emu. The early colonial accounts spell it ‘emue’,[3] Reverend Robert Knopwood spelt it as ‘emew’.[4] Other early accounts referred to it as a ‘cassowary’ and even an ‘ostrich’.[5] George Augustus Robinson recorded two indigenous words for the Tasmanian emu. The Oyster Bay Indigenous language word for emu is Pun.nune.ner and the Brune Indigenous language word is Gonanner.[6]

Description

The Tasmanian emu had not progressed to the point where it could be considered a distinct species and even its status as a distinct subspecies is not universally accepted, as it agreed with the mainland birds in measurements and the external characters used to distinguish it – a whitish instead of a black foreneck and throat and an unfeathered neck – apparently are also present, albeit rare, in some mainland birds.

There are suggestions the bird was slightly smaller than the mainland emu, but in conflict, other evidence (including descriptions of Pleistocene remains) indicates that both are similar in size.[7]

Distribution and habitat

There is much evidence to suggest Tasmanian emus were abundant in Van Diemen’s Land. John Latham’s 1823 publication affirms Charles Jeffrey’s observations in which he claims that mobs of emus were common and that a mob would consist of seventy or eighty birds.[8] The Sydney Gazette in 1803 painted an image of the Van Diemen’s Land landscape, when it reported the arrival of Lieutenant Bowen on the Lady Nelson: ‘close to the Settlement are abundance of Emues, large Kangaroos, and Swans’.[9] In 1804, it was reported that David Collins’s expedition found that ‘the emue [is] plentiful’.[10] In 1808 George Harris the surveyor travelled from Hobart Town to Launceston, and wrote that his party walked ‘thro the finest country in the world ... the quantities of kangaroos, emus and wild ducks we saw ... [was] incredible’.[11]

The Tasmanian Indigenous people’s sustainable relationship with the emu also suggests emu population numbers were significant. Indigenous people used a substance called ‘patener’. This ointment was made from a ground metal mixed with emu fat/oil and was used to mark their heads and bodies.[12] In 1831, Robinson described an Aboriginal dwelling, stating that the ground in front of this habitation was thickly strewed with the feathers of the emu, and the bones of the stately bird ... covered the ground, which the natives had broken to pieces to obtain the marrow to anoint their head and body.[6]

Relationship with humans

At a ceremony at Cape Grim on 14 April 1834, Aboriginal people danced and characterised emus by stretching out one arm to emulate the long neck of the bird.[13] The Tasmanian emu was also symbolised in Indigenous art. The depiction of the emu in ‘native drawings’ is noted in the narrative of the overland journey of Sir John and Lady Franklin from Hobart to Macquarie Harbour in 1842. The area they were referring to was subsequently called Painters Plains.[14]

The emu’s representation in ceremonial activities and art suggests a great familiarity with the emu and may further support the notion of its abundance in Van Diemen’s Land. The proliferation of places in Van Diemen’s Land named after the emu also indicates the plentiful existence of the species. Henry Hellyer, the surveyor for the Van Diemen’s Land Company, came across a river and seeing the footprints of the emu on some moist ground by the water called it Emu River. Emu Bay takes its name from that river.[15] There are also Emu Bottom, Emu Valley, Emu Flat, Emu Hill, Emu Ground, Emu Heights, Emu Plains and Emu Point.[16] There was an Emu Inn in Hobart as early as 1823, and later the Emu Tavern in Liverpool Street, Hobart.[17]

Extinction

In 1838, John Gould after his voyage to Van Diemen’s Land claimed that ‘it would require a month search, in the most remote parts of the island, before one could see any’.[18] There were warnings about the increasing rarity of the emu. In 1826, a letter from Oyster Bay stated that ‘they will soon be extinct’. In 1831, a traveller reported that emus were rarely seen in the midlands, though they were numerous to the westward. A second letter in 1832 claimed that ‘the Emu is now extinct from the midland region around Bothwell’.[19] That year dogs killed ‘a beautiful specimen of the emu’ at Oatlands. It weighed about 100 pounds (45 kg), and the skin was carefully stuffed.[20]

An article in the Hobart Town Courier in 1832 deplored the loss of the emu, comparing it to that of the dodo, 'and we mention it particularly upon the present occasion, in order to impress upon our local government the propriety of taking some steps to prevent similar annihilation of that apparently no less valuable bird our native Emu. It is now very rarely to be met with in the island.' The author suggested keeping a few pairs in an enclosed area.[21] This plea for preservation was echoed by Ronald Campbell Gunn who in 1836 reflected on an unsuccessful attempt to entice Lieutenant-Governor Arthur to respond to the plight of the Tasmanian emu, pointing out that ‘Emus are now extremely rare – and in a few years will be quite gone’.[22]

James Fenton[23] immigrated in 1834; he wrote that he never saw an emu, and only heard of one being seen near the Leven in 1839. He claimed that the emus had all disappeared from some ‘unknown cause’.[23] There are many theories about what led to the extinction of the Tasmanian emu.

_(14780637625).jpg.webp)

Hunting

The Tasmanian emu was, as were the mainland birds, hunted as a pest but more likely for food. While settlers used guns to hunt emus, the emu’s speed meant guns were not necessarily effective hunting weapons on their own.[24] The introduction of the domestic dog changed this. It was so revolutionary, that the introduction of dogs should be considered a major contributing factor to the extinction of the Tasmanian emu: Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Van Diemen’s Land did not have a domestic dog, nor were dingos present. Other than humans, the only other species to hunt the emu was the thylacine, which was an endurance hunter with a tendency to track and tire its prey. In contrast, larger domestic hunting dogs, with greater speed and size, had a formidable impact.[11]

Grass fires

In addition, the practice of setting fire to grassland and shrubland to aid in claiming land for agriculture deprived the birds of habitat. The subspecies became extinct around 1850, but this date is not very precise: mainland birds were introduced after diemenensis' disappearance (and possibly even when the last birds of the Tasmanian subspecies were still around, therefore hybridising them out of existence), but the history of emu introductions on Tasmania is not sufficiently documented to allow a more precise dating of the disappearance of diemenensis. Whether a sight record in 1865 and captive specimens that died in 1873 were of this subspecies is not known with certainty.

Fences

Fences have been blamed for causing a reduction of emu numbers in mainland Australia due to the injury incurred when an emu collides with a fence. It is highly probable that fences had the same effect in Tasmania. While it is difficult to provide absolute proof, an article published by Peregrine in The Mercury supports this claim, stating that emus could not jump fences and tended to pace along the fence until they could find an opening, otherwise they would stay behind the fence.[25]

Could the fence actually represent a larger issue relating to land use and greater competition between the emu and sheep and cattle for land, food and resources? The emus in Van Diemen’s Land probably needed fertile and sheltered lands for reproduction on a scale that would maintain their population. The process of farmers taking over, clearing and enclosing stretches of land could have had a detrimental impact on emu populations by limiting the amount of land available for the emu to flourish.[26]

Invasive rats

Another theory suggests that invasive rats could have contributed to the rapid extinction of the Tasmanian emu.[27] The extinction theory is based on historical documents that reference Tasmanian Aboriginal people talking about goanna eggs being eaten by rats. Tasmania doesn’t have goannas, therefore suggesting that this was a mistranslation of “gonanner”, an Aboriginal word for emu.[28]

Museum specimens

There are specimens of the Tasmanian emu scattered throughout the world. Within Australia, museum collections hold Tasmanian emu eggs, bones, feathers, and skeletons. However, there are only a few known Tasmanian emu skins in the world.

Knox & Walters (1994)[29] detail both the eggs and the skins of the Tasmanian emu specimens held by London's Natural History Museum.[29] It is known that, in 1838, two skin specimens were originally received by the British Museum.

The specimens in the British Museum remained uncatalogued until 1907, when the ornithologist le Souef reported that he had discovered the Gunn specimens of the now extinct Tasmanian emu.[30] The news spread quickly to Australia and, in May 1908, Robert Hall, a curator at the Tasmanian Museum, wrote to the British Museum requesting one skin to be returned to Tasmania. This correspondence does not seem to have been acknowledged and needless to say, neither skin was ever returned.[19]

On 1 January 1960, in reply to a query about the Tasmanian emu skins, the Australian ornithologist journal Emu reported that, according to the British Museum, the skins had been mounted since their rediscovery in 1907, and could no longer be found at the South Kensington site. The Museum assumed that they had been destroyed when the exhibition gallery was damaged in the blitz during the Second World War, along with many other specimens.[31] Twelve months later there was a correction. The journal reported that ‘Happily, those Emu specimens were not mounted and had been removed for safety, along with a lot of other valuable ratite material, to the museum premises at Tring, Hertfordshire’.[32] The specimens remained at the Natural History Museum premises at Tring and can be found there today.

A supposed third specimen in Frankfurt is erroneously attributed to this subspecies (Steinbacher, 1959). While it is known that the skin in Germany came from Tasmania, it is suggested that this skin may in fact be from a domesticated Australian mainland emu that had been brought into Tasmania.[33]

John Helder Wedge donated a Tasmanian emu skin to the Saffron Walden Museum in Saffron Walden in 1833.[34] It is unfortunate that, during the 1960s, the museum collections were reorganised and a large number of specimens were sent for disposal. An emu is on the disposal list according to the records of the Saffron Walden Museum.

In 2018, the Austrian Natural History Museum in Vienna displayed a taxidermed Tasmanian emu.

References

- "Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis / Tasmanian emu / Emu (Tasmanian)". Species profile and threats database. Australian Government, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- "Tasmanian emu officially extinct". The Advocate. Burnie, Tasmania. 22 August 1997. p. 11.

- "Lieutenant Governor Collin's arrival in VDL". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. 26 August 1804.

- Knopwood, Robert (1977). Nicholls, Mary (ed.). The diary of the Reverend Robert Knopwood, 1803-1838: First chaplain of Van Diemen's Land. Hobart, Tasmania: Tasmanian Historical Research Association. ISBN 0-909479-00-3. OCLC 4467573.

- "Emus at Windsor". Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser. 9 January 1824.

- Robinson, George Augustus (2008). Plomley, N.J.B. (ed.). Friendly Mission: The Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834 (2nd ed.). Launceston, Tasmania: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery / Quintus Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9775572-2-6. OCLC 271559484.

- Heupink, T.H.; Huynen, L.; Lambert, D.M. (2011). "Ancient DNA suggests dwarf and 'giant' emu are conspecific". PLOS ONE. 6 (4): e18728. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618728H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018728. PMC 3073985. PMID 21494561.

- Latham, J. (1823). A General History of Birds. Winchester, UK. p. 138.

- "[no title cited]". The Sydney Gazette. Sydney, AU. 16 October 1803.

- "[no title cited]". The Sydney Gazette. Sydney, AU. 26 August 1804.

- Boyce, James (2008). Van Diemen's Land. Black. p. 63. ISBN 9781863954136.

- "[no title cited]". The Mercury. Hobart, Tasmania. 29 January 1874.

- Macfarlane, Ian (2010). "Adolphus Schayer: Van Diemen's Land and the Berlin Papers". Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings. 57 (2): 105–118.

- Burn, D. (1955). Narrative of the Overland Journey of Sir John and Lady Franklin, and party, from Hobart Town to Macquarie Harbour 1842. Sydney, AU. p. 19.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "[no title cited]". The Advocate. Burnie, Tasmania. 31 August 1936.

- "The E.R. Pretyman index to Tasmanian place names". librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- Bryce, D. (1997). Pubs in Hobart: From 1807. Rosny Park. p. 56.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Gould, John (1865). Handbook to the Birds of Australia. Vol. II. London, UK. p. 202.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Paddle, Robert (2000). The Last Tasmanian Tiger: The history and extinction of the thylacine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78219-7. OCLC 59361805.

- "[no title cited]". Hobart Town Courier. 7 September 1832.

- "[no title cited]". Hobart Town Courier. 10 August 1832.

- Burns, T.E.; Skemp, John Rowland; Hooker, William J., Sir (1961). Van Diemen's Land Correspondents. Launceston, Tasmania: Queen Victoria Museum.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Fenton, James (1964). Bush life in Tasmania fifty years ago. London, UK: Hazel, Watson & Viney.

- Burn, David (1973). A Picture of Van Diemen's Land. Hobart, Tasmania: Cat & Fiddle Press. ISBN 0-85853-013-9. OCLC 2033882.

- "[no title cited]". The Mercury. Hobart, Tasmania. 20 July 1942.

- Davies, S.J.J.F. (2002). Ratites and tinamous: Tinamidae, Rheidae, Dromaiidae, Casuariidae, Apterygidae, Struthionidae. Bamford, Mike. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854996-2. OCLC 47756048.

- Bennett, Lachlan (9 July 2017). "Theory suggests extinction of Tasmanian emu may have been caused by rats". The Advocate. Burnie, Tasmania. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Dooley, Robert (December 2017). "From 'abundance of emues' to a rare bird in the land: The extinction of the Tasmanian emu". Tasmanian Historical Research Association. 64 (3): 4–17.

- Knox, A.; Walters, M. (1994). Extinct and endangered birds in the collections of the Natural History Museum. Tring, Hertfordshire, UK: British Ornithologists’ Club. p. 32.

- "The hundred and thirty fifth meeting of the club ... on Wednesday 16 October 1907". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. xxi (CXXXVI): 13. 20 October 1907.

- Green (1960). "Extinct Dromaius species". Emu. 60: 19. doi:10.1071/MU960019.

- Macdonald, J. (1961). "Specimens of extinct Tasmanian emu". Emu. 61 (4): 333. doi:10.1071/MU961328f.

- Hartert, Ernst (1891). Katalog Der Vogelsammlung in Museum Der Senckenbergischen Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Frankfurt Am Main [Catalog of the Birds Collected in the Museum of the Senckenberg Natural Research Society in Frankfurt on Main] (in German). Frankfurt, DE: Knauer. p. 249.

- Taylor, Rebe (Summer 2017). "Wedge politics" (PDF). SL Magazine. Vol. Summer 2017. p. 18.

- Garvey, Jillian (December 2007). "Surviving an ice age: The zooarchaeological record from southwestern Tasmania". PALAIOS. 22 (6): 583–585. Bibcode:2007Palai..22..583G. doi:10.2110/palo.2007.S06. ISSN 0883-1351. S2CID 128440384.

- le Souef, W.H.D. (1907). "Description of Dromaius novaehollandiae diemenensis". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 21: 13.

- Steinbacher, Joachim (1959). "Weitere Angaben über ausgestorbene, aussterbende, und seltene Vögel im Senckenberg-Museum" [More information on extinct, dying out, and rare birds in the Senckenberg Museum]. Senckenbergiana Biologica (in German). 40 (1–2): 1–14.