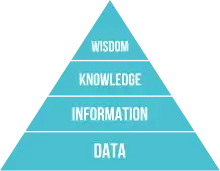

DIKW pyramid

The DIKW pyramid, also known variously as the DIKW hierarchy, wisdom hierarchy, knowledge hierarchy, information hierarchy, information pyramid, and the data pyramid,[1] refers loosely to a class of models[2] for representing purported structural and/or functional relationships between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. "Typically information is defined in terms of data, knowledge in terms of information, and wisdom in terms of knowledge".The DIKW acronym has worked into the rotation from knowledge management. It demonstrates how the deep understanding of the subject emerges, passing through four qualitative stages: "D" – data, "I" – information, "K" – knowledge and "W" – wisdom[1]

Not all versions of the DIKW model reference all four components (earlier versions not including data, later versions omitting or downplaying wisdom), and some include additional components.[3] In addition to a hierarchy and a pyramid, the DIKW model has also been characterized as a chain,[4][5] as a framework,[6] as a series of graphs,[7] and as a continuum.[8]

History

Danny P. Wallace, a professor of library and information science, explained that the origin of the DIKW pyramid is uncertain:

The presentation of the relationships among data, information, knowledge, and sometimes wisdom in a hierarchical arrangement has been part of the language of information science for many years. Although it is uncertain when and by whom those relationships were first presented, the ubiquity of the notion of a hierarchy is embedded in the use of the acronym DIKW as a shorthand representation for the data-to-information-to-knowledge-to-wisdom transformation.[9]

Many authors think that the idea of the DIKW relationship originated from two lines in the poem "Choruses", by T. S. Eliot, that appears in the pageant play The Rock, in 1934:[10]

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?[11]

Knowledge, intelligence, and wisdom

In 1927, Clarence W. Barron addressed his employees at Dow Jones & Company on the hierarchy: "Knowledge, Intelligence and Wisdom."[12]

Data, information, knowledge

In 1955, English-American economist and educator Kenneth Boulding presented a variation on the hierarchy consisting of "signals, messages, information, and knowledge".[9][13] However, "[t]he first author to distinguish among data, information, and knowledge and to also employ the term 'knowledge management' may have been American educator Nicholas L. Henry",[9] in a 1974 journal article.[14]

Data, information, knowledge, wisdom

Other early versions (prior to 1982) of the hierarchy that refer to a data tier include those of Chinese-American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan[15][16] and sociologist-historian Daniel Bell.[15].[16] In 1980, Irish-born engineer Mike Cooley invoked the same hierarchy in his critique of automation and computerization, in his book Architect or Bee?: The Human / Technology Relationship.[17][16]

Thereafter, in 1987, Czechoslovakia-born educator Milan Zeleny mapped the elements of the hierarchy to knowledge forms: know-nothing, know-what, know-how, and know-why.[18] Zeleny "has frequently been credited with proposing the [representation of DIKW as a pyramid ]... although he actually made no reference to any such graphical model."[9]

The hierarchy appears again in a 1988 address to the International Society for General Systems Research, by American organizational theorist Russell Ackoff, published in 1989.[19] Subsequent authors and textbooks cite Ackoff's as the "original articulation"[1] of the hierarchy or otherwise credit Ackoff with its proposal.[20] Ackoff's version of the model includes an understanding tier (as Adler had, before him[9][21][22]), interposed between knowledge and wisdom. Although Ackoff did not present the hierarchy graphically, he has also been credited with its representation as a pyramid.[9][19]

In 1989, Bell Labs veteran Robert W. Lucky wrote about the four-tier "information hierarchy" in the form of a pyramid in his book Silicon Dreams.[10]

In the same year as Ackoff presented his address, information scientist Anthony Debons and colleagues introduced an extended hierarchy, with "events", "symbols", and "rules and formulations" tiers ahead of data.[9][23]

In 1994 Nathan Shedroff presented the DIKW hierarchy in an information design context which later appeared as a book chapter.[24]

Jennifer Rowley noted in 2007 that there was "little reference to wisdom" in discussion of the DIKW in recently published college textbooks,[1] and does not include wisdom in her own definitions following that research.[20] Meanwhile, Zins' extensive analysis of the conceptualizations of data, information, and knowledge, in his 2007 research study, makes no explicit commentary on wisdom,[2] although some of the citations included by Zins do make mention of the term.[25][26][27]

Description

The DIKW model "is often quoted, or used implicitly, in definitions of data, information and knowledge in the information management, information systems and knowledge management literatures, but there has been limited direct discussion of the hierarchy".[1] Reviews of textbooks[1] and a survey of scholars in relevant fields[2] indicate that there is not a consensus as to definitions used in the model, and even less "in the description of the processes that transform elements lower in the hierarchy into those above them".[1][28]

This has led Israeli researcher Chaim Zins to suggest that the data–information–knowledge components of DIKW refer to a class of no less than five models, as a function of whether data, information, and knowledge are each conceived of as subjective, objective (what Zins terms, "universal" or "collective") or both. In Zins's usage, subjective and objective "are not related to arbitrariness and truthfulness, which are usually attached to the concepts of subjective knowledge and objective knowledge". Information science, Zins argues, studies data and information, but not knowledge, as knowledge is an internal (subjective) rather than an external (universal–collective) phenomenon.[2]

Data

In the context of DIKW, data is conceived of as symbols or signs, representing stimuli or signals,[2] that are "of no use until ... in a usable (that is, relevant) form".[20] Zeleny characterized this non-usable characteristic of data as "know-nothing"[18].[16]

In some cases, data is understood to refer not only to symbols, but also to signals or stimuli referred to by said symbols—what Zins terms subjective data.[2] Where universal data, for Zins, are "the product of observation"[20] (italics in original), subjective data are the observations. This distinction is often obscured in definitions of data in terms of "facts".

Data as fact

Rowley, following her study of DIKW definitions given in textbooks,[1] characterizes data "as being discrete, objective facts or observations, which are unorganized and unprocessed and therefore have no meaning or value because of lack of context and interpretation."[20] In Henry's early formulation of the hierarchy, data was simply defined as "merely raw facts",[14] while two recent texts define data as "chunks of facts about the state of the world"[29] and "material facts",[30] respectively.[9] Cleveland does not include an explicit data tier, but defines information as "the sum total of ... facts and ideas".[9][15]

Insofar as facts have as a fundamental property that they are true, have objective reality, or otherwise can be verified, such definitions would preclude false, meaningless, and nonsensical data from the DIKW model, such that the principle of garbage in, garbage out would not be accounted for under DIKW.

Data as signal

In the subjective domain, data are conceived of as "sensory stimuli, which we perceive through our senses",[2] or "signal readings", including "sensor and/or sensory readings of light, sound, smell, taste, and touch".[28] Others have argued that what Zins calls subjective data actually count as a "signal" tier (as had Boulding[9][13]), which precedes data in the DIKW chain.[8]

American information scientist Glynn Harmon defined data as "one or more kinds of energy waves or particles (light, heat, sound, force, electromagnetic) selected by a conscious organism or intelligent agent on the basis of a preexisting frame or inferential mechanism in the organism or agent."[31]

The meaning of sensory stimuli may also be thought of as subjective data:

Information is the meaning of these sensory stimuli (i.e., the empirical perception). For example, the noises that I hear are data. The meaning of these noises (e.g., a running car engine) is information. Still, there is another alternative as to how to define these two concepts—which seems even better. Data are sense stimuli, or their meaning (i.e., the empirical perception). Accordingly, in the example above, the loud noises, as well as the perception of a running car engine, are data.[2] (Italics added. Bold in original.)

Subjective data, if understood in this way, would be comparable to knowledge by acquaintance, in that it is based on direct experience of stimuli. However, unlike knowledge by acquaintance, as described by Bertrand Russell and others, the subjective domain is "not related to ... truthfulness".[2]

Whether Zins' alternate definition would hold would be a function of whether "the running of a car engine" is understood as an objective fact or as a contextual interpretation.

Data as symbol

Whether the DIKW definition of data is deemed to include Zins's subjective data (with or without meaning), data is consistently defined to include "symbols",[19][32] or "sets of signs that represent empirical stimuli or perceptions",[2] of "a property of an object, an event or of their environment".[20] Data, in this sense, are "recorded (captured or stored) symbols", including "words (text and/or verbal), numbers, diagrams, and images (still &/or video), which are the building blocks of communication", the purpose of which "is to record activities or situations, to attempt to capture the true picture or real event," such that "all data are historical, unless used for illustrative purposes, such as forecasting."[28]

Boulding's version of DIKW explicitly named the level below the information tier message, distinguishing it from an underlying signal tier.[9][13] Debons and colleagues reverse this relationship, identifying an explicit symbol tier as one of several levels underlying data.[9][23]

Zins determined that, for most of those surveyed, data "are characterized as phenomena in the universal domain". "Apparently," clarifies Zins, "it is more useful to relate to the data, information, and knowledge as sets of signs rather than as meaning and its building blocks".[2]

Information

In the context of DIKW, information meets the definition for knowledge by description ("information is contained in descriptions"[20]), and is differentiated from data in that it is "useful". "Information is inferred from data",[20] in the process of answering interrogative questions (e.g., "who", "what", "where", "how many", "when"),[19][20] thereby making the data useful[32] for "decisions and/or action".[28] "Classically," states a 2007 text, "information is defined as data that are endowed with meaning and purpose."[9][29]

Structural vs. functional

Rowley, following her review of how DIKW is presented in textbooks,[1] describes information as "organized or structured data, which has been processed in such a way that the information now has relevance for a specific purpose or context, and is therefore meaningful, valuable, useful and relevant." Note that this definition contrasts with Rowley's characterization of Ackoff's definitions, wherein "[t]he difference between data and information is structural, not functional."[20]

In his formulation of the hierarchy, Henry defined information as "data that changes us",[9][14] this being a functional, rather than structural, distinction between data and information. Meanwhile, Cleveland, who did not refer to a data level in his version of DIKW, described information as "the sum total of all the facts and ideas that are available to be known by somebody at a given moment in time".[9][15]

American educator Bob Boiko is more obscure, defining information only as "matter-of-fact".[9][30]

Symbolic vs. subjective

Information may be conceived of in DIKW models as: (i) universal, existing as symbols and signs; (ii) subjective, the meaning to which symbols attach; or (iii) both.[2] Examples of information as both symbol and meaning include:

- American information scientist Anthony Debons's characterization of information as representing "a state of awareness (consciousness) and the physical manifestations they form", such that "[i]nformation, as a phenomenon, represents both a process and a product; a cognitive/affective state, and the physical counterpart (product of) the cognitive/affective state."[33]

- Danish information scientist Hanne Albrechtsen's description of information as "related to meaning or human intention", either as "the contents of databases, the web, etc." (italics added) or "the meaning of statements as they are intended by the speaker/writer and understood/misunderstood by the listener/reader."[34]

Zeleny formerly described information as "know-what",[18] but has since refined this to differentiate between "what to have or to possess" (information) and "what to do, act or carry out" (wisdom). To this conceptualization of information, he also adds "why is", as distinct from "why do" (another aspect of wisdom). Zeleny further argues that there is no such thing as explicit knowledge, but rather that knowledge, once made explicit in symbolic form, becomes information.[4]

Knowledge

The knowledge component of DIKW is generally agreed to be an elusive concept which is difficult to define. The DIKW definition of knowledge differs from that used by epistemology. The DIKW view is that "knowledge is defined with reference to information."[20] Definitions may refer to information having been processed, organized or structured in some way, or else as being applied or put into action.

Zins has suggested that knowledge, being subjective rather than universal, is not the subject of study in information science, and that it is often defined in propositional terms,[2] while Zeleny has asserted that to capture knowledge in symbolic form is to make it into information, i.e., that "All knowledge is tacit".[4]

"One of the most frequently quoted definitions"[9] of knowledge captures some of the various ways in which it has been defined by others:

Knowledge is a fluid mix of framed experience, values, contextual information, expert insight and grounded intuition that provides an environment and framework for evaluating and incorporating new experiences and information. It originates and is applied in the minds of knowers. In organizations it often becomes embedded not only in documents and repositories but also in organizational routines, processes, practices and norms.[9][35]

Knowledge as processed

Mirroring the description of information as "organized or structured data", knowledge is sometimes described as:

- "synthesis of multiple sources of information over time"

- "organization and processing to convey understanding, experience [and] accumulated learning"

- "a mix of contextual information, values, experience and rules"[20]

One of Boulding's definitions for knowledge had been "a mental structure"[9][13] and Cleveland described knowledge as "the result of somebody applying the refiner's fire to [information], selecting and organizing what is useful to somebody".[9][15] A 2007 text describes knowledge as "information connected in relationships".[9][29]

Knowledge as procedural

Zeleny defines knowledge as "know-how"[4][18] (i.e., procedural knowledge), and also "know-who" and "know-when", each gained through "practical experience".[4] "Knowledge ... brings forth from the background of experience a coherent and self-consistent set of coordinated actions.".[9][18] Further, implicitly holding information as descriptive, Zeleny declares that "Knowledge is action, not a description of action."[4]

Ackoff, likewise, described knowledge as the "application of data and information", which "answers 'how' questions",[19][32] that is, "know-how".[20]

Meanwhile, textbooks discussing DIKW have been found to describe knowledge variously in terms of experience, skill, expertise or capability:

- "study and experience"

- "a mix of contextual information, expert opinion, skills and experience"

- "information combined with understanding and capability"

- "perception, skills, training, common sense and experience".[20]

Businessmen James Chisholm and Greg Warman characterize knowledge simply as "doing things right".[6]

Knowledge as propositional

Knowledge is sometimes described as "belief structuring" and "internalization with reference to cognitive frameworks".[20] One definition given by Boulding for knowledge was "the subjective 'perception of the world and one's place in it'",[9][13] while Zeleny's said that knowledge "should refer to an observer's distinction of 'objects' (wholes, unities)".[9][18]

Zins, likewise, found that knowledge is described in propositional terms, as justifiable beliefs (subjective domain, akin to tacit knowledge), and sometimes also as signs that represent such beliefs (universal/collective domain, akin to explicit knowledge). Zeleny has rejected the idea of explicit knowledge (as in Zins' universal knowledge), arguing that once made symbolic, knowledge becomes information.[4] Boiko appears to echo this sentiment, in his claim that "knowledge and wisdom can be information".[9][30]

In the subjective domain:

Knowledge is a thought in the individual's mind, which is characterized by the individual's justifiable belief that it is true. It can be empirical and non-empirical, as in the case of logical and mathematical knowledge (e.g., "every triangle has three sides"), religious knowledge (e.g., "God exists"), philosophical knowledge (e.g., "Cogito ergo sum"), and the like. Note that knowledge is the content of a thought in the individual's mind, which is characterized by the individual's justifiable belief that it is true, while "knowing" is a state of mind which is characterized by the three conditions: (1) the individual believe[s] that it is true, (2) S/he can justify it, and (3) It is true, or it [appears] to be true.[2] (Italics added. Bold in original.)

The distinction here between subjective knowledge and subjective information is that subjective knowledge is characterized by justifiable belief, where subjective information is a type of knowledge concerning the meaning of data.

Boiko implied that knowledge was both open to rational discourse and justification, when he defined knowledge as "a matter of dispute".[9][30]

Wisdom

Although commonly included as a level in DIKW, "there is limited reference to wisdom"[1] in discussions of the model. Boiko appears to have dismissed wisdom, characterizing it as "non-material".[9][30]

Ackoff refers to understanding as an "appreciation of 'why'", and wisdom as "evaluated understanding", where understanding is posited as a discrete layer between knowledge and wisdom.[9][19][32] Adler had previously also included an understanding tier,[9][21][22] while other authors have depicted understanding as a dimension in relation to which DIKW is plotted.[6][32]

Cleveland described wisdom simply as "integrated knowledge—information made super-useful".[9][15] Other authors have characterized wisdom as "knowing the right things to do"[6] and "the ability to make sound judgments and decisions apparently without thought".[9][29] Wisdom involves using knowledge for the greater good. Because of this, wisdom is deeper and more uniquely human. It requires a sense of good and bad, right and wrong, ethical and unethical.

Zeleny described wisdom as "know-why",[18] but later refined his definitions, so as to differentiate "why do" (wisdom) from "why is" (information), and expanding his definition to include a form of know-what ("what to do, act or carry out").[4] According to Nikhil Sharma, Zeleny has argued for a tier to the model beyond wisdom, termed "enlightenment".[16]

Representations

Graphical representation

.png.webp)

DIKW is a hierarchical model often depicted as a pyramid,[1][9] with data at its base and wisdom at its apex. In this regard it is similar to Maslow's hierarchy of needs, in that each level of the hierarchy is argued to be an essential precursor to the levels above. Unlike Maslow's hierarchy, which describes relationships of priority (lower levels are focused on first), DIKW describes purported structural or functional relationships (lower levels comprise the material of higher levels). Both Zeleny and Ackoff have been credited with originating the pyramid representation,[9] although neither used a pyramid to present their ideas.[9][18][19]

DIKW has also been represented as a two-dimensional chart[6][36] or as one or more flow diagrams.[28] In such cases, the relationships between the elements may be presented as less hierarchical, with feedback loops and control relationships.

Debons and colleagues[23] may have been the first to "present the hierarchy graphically".[9]

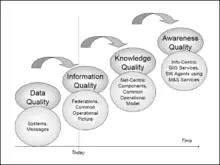

Throughout the years many adaptations of the DIKW pyramid have been produced. One evolving adaptation, in use by knowledge managers in the United States Department of Defense, attempts to show the progression transforming data to information then knowledge and finally wisdom to enable effective decisions, as well as the activities involved to ultimately create shared understanding throughout the organization and managing decision risk.[37]

Computational representation

Intelligent decision support systems are trying to improve decision making by introducing new technologies and methods from the domain of modeling and simulation in general, and in particular from the domain of intelligent software agents in the contexts of agent-based modeling.[38]

The following example describes a military decision support system, but the architecture and underlying conceptual idea are transferable to other application domains:[38]

- The value chain starts with data quality describing the information within the underlying command and control systems.

- Information quality tracks the completeness, correctness, currency, consistency and precision of the data items and information statements available.

- Knowledge quality deals with procedural knowledge and information embedded in the command and control system such as templates for adversary forces, assumptions about entities such as ranges and weapons, and doctrinal assumptions, often coded as rules.

- Awareness quality measures the degree of using the information and knowledge embedded within the command and control system. Awareness is explicitly placed in the cognitive domain.

By the introduction of a common operational picture, data are put into context, which leads to information instead of data. The next step, which is enabled by service-oriented web-based infrastructures (but not yet operationally used), is the use of models and simulations for decision support. Simulation systems are the prototype for procedural knowledge, which is the basis for knowledge quality. Finally, using intelligent software agents to continually observe the battle sphere, apply models and simulations to analyse what is going on, to monitor the execution of a plan, and to do all the tasks necessary to make the decision maker aware of what is going on, command and control systems could even support situational awareness, the level in the value chain traditionally limited to pure cognitive methods.[38]

Criticisms

Rafael Capurro, a philosopher based in Germany, argues that data is an abstraction, information refers to "the act of communicating meaning", and knowledge "is the event of meaning selection of a (psychic/social) system from its 'world' on the basis of communication". As such, any impression of a logical hierarchy between these concepts "is a fairytale".[39]

One objection offered by Zins is that, while knowledge may be an exclusively cognitive phenomenon, the difficulty in pointing to a given fact as being distinctively information or knowledge, but not both, makes the DIKW model unworkable.

[I]s Albert Einstein's famous equation "E = mc2" (which is printed on my computer screen, and is definitely separated from any human mind) information or knowledge? Is "2 + 2 = 4" information or knowledge?[2]

Alternatively, information and knowledge might be seen as synonyms.[40] In answer to these criticisms, Zins argues that, subjectivist and empiricist philosophy aside, "the three fundamental concepts of data, information, and knowledge and the relations among them, as they are perceived by leading scholars in the information science academic community", have meanings open to distinct definitions.[2] Rowley echoes this point in arguing that, where definitions of knowledge may disagree, "[t]hese various perspectives all take as their point of departure the relationship between data, information and knowledge."[20]

American philosophers John Dewey and Arthur Bentley, in their 1949 book Knowing and the Known, argued that "knowledge" was "a vague word", and presented a complex alternative to DIKW including some nineteen "terminological guide-posts".[9][41]

Information processing theory argues that the physical world is made of information itself. Under this definition, data is either made up of or synonymous with physical information. It is unclear, however, whether information as it is conceived in the DIKW model would be considered derivative from physical-information/data or synonymous with physical information. In the former case, the DIKW model is open to the fallacy of equivocation. In the latter, the data tier of the DIKW model is preempted by an assertion of neutral monism.

Educator Martin Frické has published an article critiquing the DIKW hierarchy, in which he argues that the model is based on "dated and unsatisfactory philosophical positions of operationalism and inductivism", that information and knowledge are both weak knowledge, and that wisdom is the "possession and use of wide practical knowledge.[42]

David Weinberger argues that although the DIKW pyramid appears to be a logical and straight-forward progression, this is incorrect. "What looks like a logical progression is actually a desperate cry for help."[43] He points out there is a discontinuity between Data and Information (which are stored in computers), versus Knowledge and Wisdom (which are human endeavours). This suggests that the DIKW pyramid is too simplistic in representing how these concepts interact. "...Knowledge is not determined by information, for it is the knowing process that first decides which information is relevant, and how it is to be used."[43]

See also

- Bloom's taxonomy – Classification system in education

- Higher-order thinking – Concept in education and education reform

- Intelligence cycle – Stages of intelligence information processing

- Ladder of inference – Metaphorical model of cognition and action by Chris Argyris

- Model of hierarchical complexity – Framework for scoring how complex a behavior is

- Inverted pyramid (journalism), a metaphor used by journalists and writers to prioritise and structure the most newsworthy info and important details over general info

References

- Rowley, Jennifer (2007). "The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy". Journal of Information and Communication Science. 33 (2): 163–180. doi:10.1177/0165551506070706. S2CID 17000089.

- Zins, Chaim (22 January 2007). "Conceptual Approaches for Defining Data, Information, and Knowledge" (PDF). Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 58 (4): 479–493. doi:10.1002/asi.20508. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Baskarada, Sasa; Koronios, Andy (2013). "Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom (DIKW): A Semiotic Theoretical and Empirical Exploration of the Hierarchy and its Quality Dimension". Australasian Journal of Information Systems. 18: 5–24. doi:10.3127/ajis.v18i1.748.

- Zeleny, Milan (2005). Human Systems Management: Integrating Knowledge, Management and Systems. World Scientific. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-981-02-4913-7.

- Lievesley, Denise (September 2006). "Data information knowledge chain". Health Informatics Now. Swindon: The British Computer Society. 1 (1): 14. Retrieved 8 January 2008.

- Chisholm, James; Warman, Greg (2007). "Experiential Learning in Change Management". In Silberman, Melvin L. (ed.). The Handbook of Experiential Learning. Jossey Bass. pp. 321–40. ISBN 978-0-7879-8258-4.

- Duan, Yucong; Shao, Lixu; Hu, Gongzhu; Zhou, Zhangbing; Zou, Quan; Lin, Zhaoxin (2017). "Specifying architecture of knowledge graph with data graph, information graph, knowledge graph and wisdom graph". 2017 IEEE 15th International Conference on Software Engineering Research, Management and Applications (SERA). IEEE. pp. 327–332. doi:10.1109/SERA.2017.7965747. ISBN 978-1-5090-5756-6. S2CID 34096869.

- Choo, Chun Wei; Don Turnbull (September 2006). Web Work: Information Seeking and Knowledge Work on the World Wide Web. Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 29–48. ISBN 978-0-7923-6460-3.

- Wallace, Danny P. (2007). Knowledge Management: Historical and Cross-Disciplinary Themes. Libraries Unlimited. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-1-59158-502-2.

- Lucky, R. W. (1989). Silicon dreams : information, man, and machine. Internet Archive. New York : St. Martin's Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-312-02960-9.

- Eliot, T. S. "Choruses from " The Rock "". Poetry Nook.

- "Knowledge, Intelligence and Wisdom: an Address to the Staff of Dow, Jones & Co", 1927.

- Boulding, Kenneth (1955). "Notes on the Information Concept". Exploration. Toronto. 6: 103–112. CP IV, pp. 21–32.

- Henry, Nicholas L. (May–June 1974). "Knowledge Management: A New Concern for Public Administration". Public Administration Review. 34 (3): 189–196. doi:10.2307/974902. JSTOR 974902.

- Cleveland, Harlan (December 1982). "Information as a Resource". The Futurist: 34–39.

- Sharma, Nikhil (4 February 2008). "The Origin of the "Data Information Knowledge Wisdom" Hierarchy". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Cooley, Mike (1980). Architect or Bee?: The Human / Technology Relationship. Monroe: South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-131-4.

- Zeleny, Milan (1987). "Management Support Systems: Towards Integrated Knowledge Management". Human Systems Management. 7 (1): 59–70. doi:10.3233/HSM-1987-7108.

- Ackoff, Russell (1989). "From Data to Wisdom". Journal of Applied Systems Analysis. 16: 3–9.

- Rowley, Jennifer; Richard Hartley (2006). Organizing Knowledge: An Introduction to Managing Access to Information. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-0-7546-4431-6.

- Adler, Mortimer Jerome (1970). The Time of Our Lives: The Ethics of Common Sense. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-03-081836-3.

- Adler, Mortimer Jerome (1986). A Guidebook To Learning For The Lifelong Pursuit Of Wisdom. Collier Macmillan. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-02-500340-8.

- Debons, Anthony; Ester Horne (1988). Information Science: An Integrated View. Boston: G. K. Hall. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-8161-1857-1.

- Jackson, Robert (1999). Information Design. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0262100694.

- Dodig-Crnković, Gordana, as cited in Zins, id., at pp. 482.

- Ess, Charles, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 482-83.

- Wormell, Irene, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 486.

- Liew, Anthony (June 2007). "Understanding Data, Information, Knowledge And Their Inter-Relationships". Journal of Knowledge Management Practice. 8 (2). Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Gamble, Paul R.; John Blackwell (2002). Knowledge Management: A State of the Art Guide. London: Kogan Page. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7494-3649-0.

- Boiko, Bob (2005). Content Management Bible (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Wiley. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7645-4862-8.

- Harmon, Glynn, as cited by Zins, id., at p. 483.

- Bellinger, Gene; Durval Castro; Anthony Mills (2004). "Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom". Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Debons, Anthony, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 482.

- Albrechtsen, Hanne, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 480.

- Davenport, Thomas H.; Laurence Prusack (1998). Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. pp. 5. ISBN 978-0-585-05656-2.

- Choo, Chun Wei (May 10, 2000). "The Data-Information-Knowledge Continuum". Web Work: Information Seeking and Knowledge Work on the World Wide Web. Retrieved 9 January 2009.

- "US Army Techniques Publication (ATP) 6-01.1, Techniques for Effective Knowledge Management" (PDF). March 2015. Retrieved 2023-06-29.

- Tolk, Andreas (2005). "An agent-based Decision Support System Architecture for the Military Domain". Intelligent Decision Support Systems in Agent-Mediated Environments. 115: 187–205.

- Rafael Capurro, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 481

- Poli, Roberto, as cited in Zins, id., at p. 485.

- Dewey, John; Arthur F. Bentley (1949). Knowing and the Known. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 58, 72–74. ISBN 978-0-8371-8498-2.

- Frické, Martin (2009). "The Knowledge Pyramid: A Critique of the DIKW Hierarchy". Journal of Information Science. 35 (2): 131–142. doi:10.1177/0165551508094050. hdl:10150/105670. S2CID 2973966.

- Weinberger, David (2 February 2010). "The Problem with the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom Hierarchy". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Further reading

- Hey, Jonathan (December 2004). "The Data, Information, Knowledge, Wisdom chain: the metaphorical link" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 December 2007. Retrieved 2 October 2016.