Dachau camp trial

The Dachau camp trial (German: Dachau-Hauptprozess) was the first mass trial of the Dachau trials, a series of trials against war criminals held by the United States Army on the premises of the Dachau concentration camp. The main trial took place from 15 November to 13 December 1945. Forty people were charged with war crimes in connection with the Dachau concentration camp and its subcamps. The trial ended with 40 convictions, including 36 death sentences, of which 28 were carried out. The official name of the case was United States of America vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al. - Case 000-50-2.[1] The main trial served as a "parent case" for 123 subsequent cases. In the subsequent trials, all crimes that were established in the main trial were taken as proven, significantly shortening their duration relative to the parent case. The Dachau trials consisted of 6 total parent trials, each with their own subcases, and were held between 1945 and 1948. In total, there were 489 Dachau trials,[2] of which 394 were held within the confines of the camp itself.[3]

Background

When the United States Army advanced into German-occupied territory during the final phase of the Second World War, its troops were often confronted, sometimes in the middle of battles, with traces of the crimes committed in concentration camps. The care of the mostly emaciated and seriously ill "Muselmänner",[lower-alpha 1] and the burial of the thousands of prisoners who had died by exhaustion during death marches or by shooting proved to be a difficult task for the US Army.[4]

Shortly before the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp, which took place on 29 April 1945, US soldiers had already reached the satellite camps, including the Kauferinger Camp Complex. Like other subcamps, the subcamp Kaufering IV had been evacuated shortly before the invasion of the US Army on 28 April 1945. During the evacuation, SS men set fire to the barracks. American soldiers found the corpses of about 360 prisoners in Kaufering IV; it is not certain whether these incapacitated marchers were burned alive or had been murdered before.[5] In the main camp, the soldiers first encountered the Buchenwald death train, where up to 2,000 dead prisoners were found in over 38 train wagons. Members of the US Army also discovered many unburied bodies inside the camp. These and other final phase crimes committed in the Dachau concentration camp and its subcamps led to numerous deaths in the last weeks of the war. Even after liberation, more than 2,200 former prisoners died as a result of concentration camp detention and the still rampant typhoid epidemic.[6]

Against this background, American investigators, operating in the framework of the War Crimes Program, began investigations to establish the perpetrators of these crimes. The investigations commenced on 30 April 1945, just one day after the camp's liberation, and were completed on 7 August 1945. Investigators interviewed witnesses, secured evidence and took photographs of the crimes. Many perpetrators were soon caught and interned, including Martin Weiß, predecessor of the last camp commander Eduard Weiter. The investigation report, simply titled Dachau, was completed on 31 August 1945 and formed the basis for the arraignment and thus the Dachau camp trial.[7]

Legal basis and indictment

The charge was based on Directive JCS 1023/10 which was issued by the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 15 July 1945. The directive, later replaced by Control Council Law No 10 of 20 December 1945, empowered the American commander-in-chief Dwight D. Eisenhower to conduct military court trials of war criminals in occupied territories. Further decrees regulated jurisdiction and the rights of the accused in military court trials.[8]

The indictment, which was drawn up on 2 November 1945 and subsequently served to the defendants, comprised two main charges, which were brought together under the heading "violation of the customs and laws of war". The defendants were charged with war crimes committed against Allied civilians and (Allied) prisoners of war in the Dachau concentration camp and its satellite camps from early January 1942 to the end of April 1945. Initially, only crimes committed against citizens of the Allies of World War II were prosecuted; German crimes against German citizens were not prosecuted in the aftermath of the war and generally only tried later in German courts. The defendants were accused of having participated unlawfully and intentionally in the mistreatment and killing of Allied civilians and prisoners of war in a coordinated action. In addition to the general participation in the crimes committed in the Dachau Concentration Camp, the bill of indictment also listed specific Exzesstaten[lower-alpha 2] that were attributed to individual defendants.[9]

The defendants were accused of joint action (common purpose), which assumed an approving participation in a system of killings, mistreatment and inhuman neglect and therefore implied a presumption of guilt.[10] Therefore, the prosecution had to prove that "each of the accused was aware of this system, that he knew about what was happening to the prisoners, and it had to prove to everyone that in his place of administration, the organisation of the camp, he supported this system through his behaviour, his activity, the functioning of this system, he participated in this functioning".[lower-alpha 3][11] If this evidence was provided, the individual sentencing varied according to the nature and extent of an individual's participation. This legal construct, which did not require that individual proof of the offence be provided for a conviction, was foreign to the European legal tradition.[12]

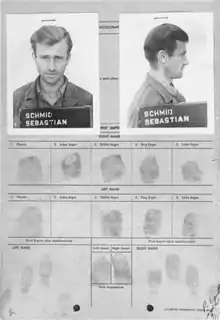

Originally, 42 members of the former camp administration were to be indicted in the Dachau camp trial. However, since Hans Aumeier and Johannes Baier were not present and the indictment could not be served on them, they were removed from the list of defendants at the beginning of the trial. Beier was later sentenced to death in a side trial, but the sentence was commuted to prison. Aumeier was sentenced to death in the Auschwitz trial, following his extradition to Poland. He was executed in Krakow in January 1948. The remaining group of 40 accused comprised 32 members of the camp team, five doctors and three prisoner functionaries who had held leading positions in the camp. Among the 32 members of the camp team was were former camp commander Martin Weiß, his adjutant Rudolf Suttrop and Johann Kick, head of the Politische Abteilung. The accused doctors included Claus Schilling, three camp doctors and a military doctor. With the exception of the Austrian Fridolin Karl Puhr and Johann Schöpp, a Volksdeutscher from Romania, all the accused were German citizens.[13]

Trial and judgment

On 30 October 1945, U.S. Army headquarters ordered the establishment of a military tribunal to conduct the Dachau trial. The tribunal was set up on 2 November 1945. It was presided by major general John M. Lentz, who, like his seven associate judges, wore a uniform during the trial. The prosecution, led by Attorney General William Denson, was composed of a total of four American officers. The defence was supported by five American officers and the German lawyer Hans von Posern. Since the language of the court was English, interpreters had to translate the proceedings. Trial observers from Allied states were to take part in the proceedings.[14]

May it please the court, we expect the evidence to show that during the time alleged, a scheme of extermination was in process here at Dachau. We expect the evidence to show that the victims of this planned extermination were civilians and prisoners of war, individuals unwilling to submit themselves to the yoke of Nazism. We expect to show that these people were subjected to experiments like guinea pigs, starved to death, and at the same time worked as hard as their physical bodies permitted; that the conditions under which these people were housed were such that disease and death were inevitable. Further, we expect to show that during the time that Germany overran Europe, these people were subjected to utterly inhuman treatment, and that each of these accused constituted a cog in this machine of extermination.

— Chief prosecutor William D. Denson, opening statement on 15 November 1945, quoted in Greene 2003, p. 44.

The proceedings were opened on 15 November 1945 at 10 a.m., with the prosecution outlining the allegations against the accused. The military judges then established the lawfulness of the court and its jurisdiction over the defendants. The conclusion of the initial phase of the trial was interrupted by two motions for dismissal by the defence. The first motion challenged the jurisdiction of the court. The second claimed that the period during which the crimes had been committed was not defined precisely enough. A third motion referred to the small number of defence lawyers relative to the 40 defendants, claiming that in the case of individual defendants making incriminating statements about their co-defendants, the establishment of an effective defence strategy would be significantly impeded. Hence, they asked for the trial to be split into individual trials. The tribunal dismissed all three motions. It held that the court's jurisdiction was based on the defendants' status as war criminals who were not covered by laws governing the treatment of prisoners of war because the crimes had been committed before they were taken into custody. The second motion was rejected on the grounds that the accused were not primarily charged with individual crimes, but with jointly committing a crime. The motion for division of the proceedings into individual trials was dismissed for the same reason.[15]

The chairman then read out the indictment and explained the rights of the accused in the proceedings. When asked how they plead, the defendants all answered "not guilty". The prosecution then outlined its view of facts of the case and presented evidence. Among the 139 pieces of admitted evidence were 60 photographs, the camp's death books from 1941 and 1942, other incriminating documents and the defendants' testimony. Among the 69 witnesses for the prosecution were former prisoners and officers of the U.S. Army who had been involved in the liberation of Dachau concentration camp and the documentation of the crimes committed there.The officers testified to the bodies in the evacuation train from Buchenwald and the catastrophic conditions in the main camp at the time of liberation. Former prisoners then testified to the inhumane living conditions the camp, including clothing, nutrition, accommodation, forced labour, epidemics, medical experiments, selections and executions, mistreatment and killings. In addition to the conditions in the main camp, the catastrophic living conditions in the satellite camps were described.[16]

The defence responded with 93 witnesses – including the accused – and 27 admitted pieces of evidence. Both the defence and prosecution cross-examined witnesses.[17]

Those defendants who had been members of the camp staff were accused of mistreating and sometimes killing prisoners; another set of crimes included participation in executions and crimes related to the camp evacuation. The camp doctors and medical staff were charged with taking part in executions by declaring the deaths of the executed and in some cases by participating in the selection, mistreatment, and killing of prisoners. The commandant's staff were accused of bearing the primary responsibility for the disastrous conditions in the camp, thus enabling the system of killings, mistreatment and inhumane neglect. Two of the three prisoner functionaries were accused of mistreating and killing prisoners. The other was accused of participating in executions. The defendants minimised the crimes, invoking Befehlsnotstand[lower-alpha 4] or denying that they were at the scene of the crimes while they were committed.[18]

Special attention was paid to 74 year old Claus Schilling, who was by far the oldest defendant in the Dachau camp trial. Schilling, who was neither a member of the NSDAP nor of the SS, held a doctorate and habilitation in tropical medicine. A respected physician, he had studied under Robert Koch and specialised in malaria research beginning in 1898. Even after his retirement in 1936, Schilling continued his research work and was able to convince Heinrich Himmler of the necessity of developing a malaria vaccine for the war. Soon afterwards, Schilling was provided with an experimental station in the Dachau concentration camp to conduct his malaria studies. From February 1942 to early April 1945, 1,000 to 1,200 concentration camp prisoners were deliberately infected with malaria and subsequently treated with drugs on a trial basis. More than 100, but possibly up to 400, prisoners died as a result of these experiments.[19]

Schilling did not deny that the experiments had been carried out. He justified his victims' suffering as being in the interest of science. He therefore asked the court to allow him to complete and document his experiments. Moreover, he claimed that he had nothing to do with the events in the camp itself. The military court rejected Schilling's argument.[20]

In his final plea, Chief Prosecutor Denson highlighted the occurrence of a continuous crime. He said that through their participation and cooperation in the Dachau system, all the accused had enabled the crimes and were therefore all to be found guilty. This included the SS-appointed Kapos, who he deemed co-responsible for the functioning of the concentration camp. Denson did not accept the defendants' claim of Befehlsnotstand, arguing that it did not release them from responsibility for war crimes. Denson did not see any mitigating circumstances for the accused and therefore pleaded for hard sentences.[21]

The defence lawyers attacked the allegation of common design, stating that it was not part of European legal tradition and claiming that it had been applied to the defendants in an arbitrary manner. They reasoned that the trial could only take place because the doctrine had been applied, since proof of individual culpability had not been provided for many of the accused. The defence stated that in the case of former camp commander Weiß, even witnesses for the prosecution had pointed out that the conditions in the Dachau concentration camp had noticeably improved under his leadership. They further claimed that in some cases false witness statements had been used in court and that the fact that some defendants had been involuntarily called to serve in the camp had not been taken into account. In summarising their argument, the defence lawyers stated that the main culprits had to be found in the Nuremberg Trial and that the Dachau camp trial was guided by a desire for retaliation.[22]

The tribunal's chairman announced the sentences on 13 December 1945. 36 death sentences, one sentence of life imprisonment and three other prison sentences with the obligation to perform forced labour were imposed. In its justification of judgment, the court again pointed out the criminal nature of the jointly committed offence, which made it necessary to sentence all the accused.[23]

Former prisoner Eugen Seybold identifies Fritz Hintermayer, 22 November 1945

Former prisoner Eugen Seybold identifies Fritz Hintermayer, 22 November 1945 Polish priest Theodore Korcz (left) reads from the Malaria protocols on 22 November 1945

Polish priest Theodore Korcz (left) reads from the Malaria protocols on 22 November 1945 Wilhelm Wagner during his testimony on 30 November 1945

Wilhelm Wagner during his testimony on 30 November 1945 Former prisoner Helmuth Breiding identifies Friedrich Wetzel on 22 November 1945

Former prisoner Helmuth Breiding identifies Friedrich Wetzel on 22 November 1945 Friedrich Wetzel (right) during his testimony on 29 November 1945

Friedrich Wetzel (right) during his testimony on 29 November 1945 Friedrich Wetzel (seen from the back with number 40) during the delivery of the verdict on 13 December 1945

Friedrich Wetzel (seen from the back with number 40) during the delivery of the verdict on 13 December 1945

Individual sentences

| Name | Rank | Function | Exzesstat[lower-alpha 2] | Sentence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Martin Weiß | SS-Obersturmbannführer | Camp commander | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 | |

| Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop | SS-Obersturmführer | Adjutant of the camp commander | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 | |

| Michael Redwitz | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Schutzhaftlagerführer | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Friedrich Wilhelm Ruppert | SS-Obersturmbannführer | Schutzhaftlagerführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, participating in executions | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Wilhelm Welter | SS-Hauptscharführer | Arbeitsdienstführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, participating in selections | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Josef Jarolin | SS-Obersturmführer | Schutzhaftlagerführer | Mistreatment and killing of prisoners | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Franz Xaver Trenkle | SS-Hauptscharführer | Rapportführer and vice Schutzhaftlagerführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, participating in selections of inmates for either execution or slave labour | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Wilhelm Tempel (SS-Member) | SS-Scharführer | Arbeitsdienstführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Engelbert Valentin Niedermeyer | SS-Unterscharführer | Blockführer, served at the crematory command | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Josef Seuß | SS-Hauptscharführer | Rapportführer | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Leonhard Anselm Eichberger | SS-Hauptscharführer | Rapportführer | Participating in executions | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Alfred Kramer (SS-member) | SS-Oberscharführer | Commander of subcamp Kaufering Nr. 1 | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Wilhelm Wagner (SS member) | SS-Hauptscharführer | Commander of the prisoner laundry | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Johann Kick | SS-Obersturmführer | Commander of the Politische Abteilung | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Vinzenz Schöttl | SS-Obersturmführer | vice commander of the Kaufering subcamp complex | Mistreatment of prisoners, killing of a prisoner | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Fritz Hintermayer | SS-Obersturmbannführer | 1. Camp doctor | Killing of two pregnant female prisoners by injection, preparing the execution of seven mentally ill prisoners, participation in executions to confirm the death of the executed | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Johann Viktor Kirsch | SS-Hauptscharführer | Commander of subcamp Kaufering Nr. 1 | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Johann Baptist Eichelsdörfer | Hauptmann in the Wehrmacht | Commander of subcamps Kaufering Nr. 4, 7 and 8 | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Otto Förschner | SS-Sturmbannführer | Commander of the Kaufering subcamp complex | Mistreatment of prisoners, killing of a prisoner | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Walter Adolf Langleist | SS-Oberführer | Commander of the guard crew, camp commander of the Mühldorf concentration camp complex | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Claus Schilling | Doctor of tropical diseases | Leader of the malaria experiments at the camp | Carrying out malaria experiments on prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Arno Lippmann | SS-Obersturmführer | Leader of subcamps Kaufering Nr. 2 und 7, Schutzhaftlagerführer under Michael Redwitz | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Franz Böttger | SS-Oberscharführer | Arbeits- und Rapportführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, killing of a prisoner, participating in executions | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Otto Moll | SS-Hauptscharführer | Division of work in the Kaufering side camps | Mistreatment of prisoners, fatally shooting prisoners during the evacuation march | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Anton Endres | SS-Oberscharführer | SS-Sanitätsdienstgrad | Mistreatment of prisoners, killing of a prisoner by injection, participating in two executions | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Simon Kiern | SS-Hauptscharführer | Blockführer | Mistreatment of prisoners, killing of a prisoner, participating in three executions | Death, executed on 28 May 1946 |

| Fritz Becher | Prisoner functionary | Blockältester at the Priest Barracks | Mistreatment of prisoners, sometimes resulting in death | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Christof Ludwig Knoll | Prisoner functionary | Blockältester and Kapo | Mistreatment and killing of prisoners | Death, executed on 29 May 1946 |

| Hans Eisele | SS-Hauptsturmführer | 2. Camp doctor | Participating in executions to confirm the death of the executed | Death, commuted to life imprisonment with hard labor |

| Wilhelm Witteler | SS-Sturmbannführer | 1. Camp doctor | Participating in executions to confirm the death of the executed | Death, commuted to 20 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Fridolin Karl Puhr | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Chief troop doctor | Participating in executions to confirm the death of the executed | Death, commuted to 20 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Otto Schulz | SS-Untersturmführer | Plant manager of the Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke in Dachau | Mistreatment of prisoners | Death, commuted to 20 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Fritz Degelow | SS-Sturmbannführer | Commander of the guards at Dachau | Head of an evacuation transport | Death, commuted to 10 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Emil Mahl | Prisoner functionary | Kapo at the crematory of KZ Dachau | Participating in executions | Death, commuted to 10 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Sylvester Filleböck | SS-Untersturmführer | Supply officer at KZ Dachau | Death, commuted to 10 years imprisonment with hard labor | |

| Friedrich Wetzel | SS-Hauptsturmführer | Leader of the administration at KZ Dachau | Death, commuted to 10 years imprisonment with hard labor | |

| Peter Betz (SS-Hauptscharführer) | SS-Hauptscharführer | Rapportführer, Kommandoführer and employed in the office of the camp commandant | Mistreatment of prisoners | Life imprisonment with hard labor, commuted to 15 years imprisonment with hard labor |

| Hugo Lausterer | SS-Scharführer | Leader of the command in the Feldafing side camp | 10 years imprisonment with hard labor; commuted to 8 years imprisonment with hard labor | |

| Albin Gretsch | SS-Unterscharführer | Guard at Dachau | 10 years imprisonment with hard labor; commuted to 7 years imprisonment with hard labor | |

| Johann Schöpp | SS-Mann | Guard at Dachau and the Feldafing side camp | 10 years imprisonment with hard labor, commuted to 5 years imprisonment with hard labor |

Review procedure

Arthur Haulot, President of the International Committee of Dachau Prisoners, submitted a request for clemency for the three prisoner functionaries who had been sentenced to death, arguing that they were both perpetrators and victims and therefore had to be treated differently from the other accused.[24]

For many other defendants, petitions for clemency were received from families, friends, colleagues and even neighbours. This was also the case for the accused tropical physician Schilling, for whom petitions for clemency were received from colleagues at the Robert Koch Institute, the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine and the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, among others. The petitions for clemency for Schilling expressly referred to his contributions to science, his apolitical attitude and his impeccable conduct. According to some of the petitions for clemency, Schilling was a passionate researcher who had not deliberately planned the death of test subjects during his series of experiments, but on the contrary had wanted to save lives.[25]

Ganz unpolitisch eingestellt, liebte er nur seine Wissenschaft, seine Geige und seine Frau.

Entirely unpolitical, he only loved his science, his violin and his wife.

In the review proceedings, the defence sought an acquittal for the defendants Mahl, Becher, Knoll, Schöpp, Gretsch, Lausterer, Betz, Suttrop, Puhr, Witteler and Eisele. In their view, no materially incriminating statements or evidence had been produced for these defendants. Furthermore, they argued that the sentences passed against the other defendants were disproportionately harsh.[26]

During the cassation proceedings, which went through two review bodies, the individual participation of the accused in the acts committed jointly played a significant role. After examining the trial documents and weighing the arguments put forward by the prosecution and defence, the judgments were largely confirmed. The death sentence for camp doctor Eisele, who was later also accused in the Buchenwald Trial, was commuted to life imprisonment. Similarly, Puhr's and Mahl's death sentences were commuted to prison sentences and Schöpp's sentence was reduced to five years. In the case of Mahl, his comprehensive willingness to testify taken into account; the courts also considered his participation in the crimes to be less severe than for the other two prisoner functionaries. In the case of Eisele, for whom participation in individual cases of mistreatment could not be proven, the improvement of medical care in the camp under his purview and the very short time he spent in Dachau was taken into account. In the case of Puhr, the army doctor, the commutation of the sentence was justified by the fact that he had only served in the camp as a substitute. The recommendation to reduce Schöpp's prison sentence by half was justified by his forced conscription to the Waffen-SS, his insignificant function in the camp compared with the other defendants, and the fact that he had not mistreated any prisoners. After the second review panel concluded its proceedings, the death sentences of Witteler, Schulz, Degelow, Wetzel and Filleböck were also commuted to prison sentences. According to the court, Witteler, Schulz, Wetzel and Filleböck had played an important role in the camp, but they had also tried to improve conditions in the camp in various ways. Although Degelow had led an evacuation march, he had endeavoured to ensure that the march was carried out in a humane manner and had only spent a few days in the camp in person. The commander of the American armed forces followed the recommendations of the two review bodies and also confirmed the remaining verdicts.[27]

Execution of the sentences

Following the delivery of the judgment, the convicted individuals were transferred to various penitentiaries, principally the war crimes prison in Landsberg. Of the 36 death sentences pronounced, 28 were executed by hanging on 28 and 29 May 1946 at Landsberg Prison. The executions took place in camera.[28]

Prison sentences were successively reduced during review proceedings or as a result of clemency petitions. By the mid-1950s, all prisoners convicted in the Dachau camp trial were released on the basis of good conduct, amnesty or on health grounds.[29]

Evaluations and effects

The sentences in the Dachau camp trial were harsh when compared to subsequent concentration camp trials. The main reasons for this were that the trial was held in the immediate aftermath of the war and the fact that the judges of the military tribunal were still able to gain a comprehensive picture of the catastrophic conditions after the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp in the immediate aftermath of its liberation. In the later Dachau concentration camp trials, the responsible judges could no longer draw on this experience, which played an important role in determining the outcomes of the Dachau camp trial.[30] In the course of the Cold War – in which the Western Allies sought an alliance with West Germany – retrials led to the successive mitigation of the sentences and thus also the early release of the prisoners from Landsberg Prison began.[31]

As was the case in other war crimes trials conducted by the allies, the focus of the Dachau camp trial was initially punishment and atonement for Nazi crimes in accordance with the rule of law. An additional goal was to inform the population about the Nazi crimes and to clarify the criminal character of the acts of violence. The trials were intended to initiate a process of collective reflection among the German population in order to establish a culture of rule of law and democracy in post-war Germany. The highly symbolic site of Dachau, the collective shock of the news and recordings of the violent crimes in the concentration camps had a re-educative effect during the early post-war period in Germany, as is evidenced in contemporary media publications. However, the initial shock at the atrocities in the concentration camps was followed by repression and a sense of solidarity with the Landsberg prisoners in large sections of the German population.[32]

Side trials

The Dachau camp trial was followed by 121 side proceedings with about 500 other defendants, which took place in the period between 11 October 1946 and 11 December 1947. Due to the large number of subsidiary proceedings, some trials were conducted in parallel. Most of the accused were camp staff, with some camp doctors and prisoner functionaries also being tried. The secondary proceedings were based on the Dachau camp trial and therefore took place in a shortened form. These proceedings usually had between one and nine SS members of lower ranks as the defendants and rarely lasted longer than a few days. The trials mainly dealt with the mistreatment and killing of Allied prisoners committed in Dachau concentration camp and its subcamps. The Mühldorf Trial against the camp personnel of the Dachau Mühldorf concentration camp complex was, however, conducted as an independent main trial.[33] Three of the 121 secondary proceedings require special attention, as they concerned a former camp commander and his adjudant, an SS doctor as well as a Rapportführer whose death sentence attracted nationwide attention:

- In Case No. 000-50-2-23 US vs. Alex Piorkowski et al., the former camp commander Alex Piorkowski and his Adjudant Heinrich Detmers, were tried from 6 to 17 January 1947. Piorkowski had been commander of Dachau between February 1940 and August 1942 and Detmers had been his adjutant from 1940 to February 1942. Like the defendants in the main trial, both were accused of war crimes against Allied civilians and prisoners of war and pleaded "not guilty" after reading the indictment. The main charges against Piorkowski were that he had carried out executions of Soviet prisoners of war, conducted pseudo-medical experiments on prisoners and that he had arbitrarily mistreated of prisoners under his purview. The court accused Detmers of collaborating in these crimes. The two defendants, who remained silent during the trial on the advice of their American defence lawyers, were found guilty despite the dedicated efforts of their lawyers. Following review proceedings and petitions for clemency, the death sentence against Piorkowski was upheld, but Detmers' initial fifteen-year prison sentence was reduced to five years imprisonment. Detmers was later retried in the Dora Trial; Piorkowski was executed by hanging in Landsberg on 22 October 1948.[34]

- Between 24 November and 11 December 1947, camp doctor Rudolf Brachtel and prisoner functionary Karl Zimmermann were tried (Case No. 000-50-2-103 US vs. Rudolf Brachtel et al.). Brachtel was accused of having deliberately infected prisoners with malaria as a temporary assistant to Claus Schilling and of having performed medically unnecessary liver punctures. Zimmermann was accused of mistreating prisoners and killing them with phenol injections. However, the accusations against Zimmermann, who had taken over his post from Josef Heiden, could not be sustained. Both defendants were eventually acquitted.[35]

- Defendant Georg Schallermair was tried from 18 to 23 September 1947 (Case No. 000-50-2-121 US vs. Georg Schallermair). Schallermair, a former report leader in the Mühldorf concentration camp complex, was accused of being partly responsible for the catastrophic conditions in the camp due. Furthermore, Schallermair had evidently beaten prisoners to death. Schallermair was found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging on 23 September 1947. This sentence was upheld in the review proceedings.[36] In the Federal Republic of Germany, a campaign to abolish the death penalty began in 1950, supported by prominent members of society. For example, the Minister of Justice Thomas Dehler asked President Theodor Heuss to submit requests for clemency for Schallermair and Hans-Theodor Schmidt, who was sentenced to death in the Buchenwald main trial, to General Thomas T. Handy.[37] Handy, who had previously converted eleven death sentences into prison sentences, however, rejected this request, saying:

Georg Schallermair war als Führer eines Rollkommandos direkt für die Gefangenen in Mühldorf, einem Nebenlager von Dachau, verantwortlich. Er selbst schlug viele Gefangene derart, dass sie an den Folgen starben. Von 300 Menschen, die im Herbst 1944 in das Lager gebracht wurden, waren nach vier Monaten nur 72 am Leben. Täglich besuchte er mit einem gefangenen Zahnarzt das Leichenhaus, um den Toten die Goldzähne auszubrechen. Es gibt keine Tatsachen oder Argumente, die in diesem Falle Gnade in irgendeiner Weise rechtfertigen könnten.

Georg Schallermair, as leader of the roll command, was directly responsible for the prisoners in Mühldorf, a subcamp of Dachau. He personally beat many prisoners so badly that they died of the consequences. Of 300 people brought to the camp in autumn 1944, only 72 were alive after four months. Every day, he visited the mortuary with a prisoner dentist to break out the gold teeth of the dead. There are no facts or arguments which could in this case justify mercy in any way.

— quoted in Wilmes 2001.

Schallermair and Schmidt were executed by hanging at Landsberg Prison on 7 June 1951, together with Oswald Pohl and four other death row inmates whose death sentences had not been reduced. These were the last death sentences to be carried in Landsberg.[38][39]

Notes

- A slang term used among captives to describe concentration camp prisoners suffering from a combination of exhaustion and starvation

- In German historiography, "Exzesstat" refers to acts of violence in war times that are committed without any direct order by a superior. See e.g. Hartmann 2010, p. 518, footnote 10

- "jeder der Angeklagten sich über dieses System im klaren war, dass er wusste von dem, was mit den Häftlingen geschah, und sie musste jedem nachweisen, dass er an seinem Platz der Verwaltung, der Organisation des Lagers durch sein Verhalten, seine Tätigkeit, das Funktionieren dieses System unterstützte, an diesem Funktionieren teilhatte"

- "Befehlsnotstand" refers to a situation in which refusal to perform a crime would seriously endanger the person violating the order.

References

- Bryant 2020, p. 154.

- Sigel 2019.

- Form & Bryant 2011, p. 30.

- Greiser 2007, p. 160f.

- Benz & Distel 2005, p. 367f.

- Zámečník 2007, p. 360f, 387f, 398f.

- Sigel 1992, p. 16ff, 48.

- Bryant 2007, pp. 109–111; Lessing 1993, p. 58ff; Sigel 1992, p. 35f.

- US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al. 1945, p. 3ff; Lessing 1993, p. 83f

- US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al. 1945, p. 3ff.

- Sigel 1992, p. 44.

- Freund 2001.

- Lessing 1993, p. 91f.

- Lessing 1993, p. 82f, 92f; Sigel 1992, p. 40f.

- Lessing 1993, pp. 91–117; Sigel 1992, p. 44.

- Lessing 1993, p. 117f, 144ff; Sigel 1992, p. 47f.

- Sigel 1992, p. 52f.

- US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al. 1945; Bryant 2007, p. 112.

- Bryant 2007, p. 115f; Sigel 1992, p. 71f.

- Bryant 2007, p. 115f; Sigel 1992, p. 71f.

- Lessing 1993, p. 238f; Sigel 1992, p. 56ff.

- Sigel 1992, p. 59f.

- Sigel 1992, p. 60f.

- Bryant 2007, p. 115f; Sigel 1992, p. 71f.

- Bryant 2007, p. 115f; Sigel 1992, p. 71f.

- Sigel 1992, p. 63f.

- Lessing 1993; Sigel 1992, p. 65f.

- Lessing 1993, pp. 251, 270; Sigel 1992, p. 75.

- Sigel 1992, p. 75.

- Bryant 2007, p. 120f.

- Frei 2003, p. 133-306.

- Greiser 2007, p. 167ff.

- Sigel 1992, p. 76f, 109f; Bryant 2007, p. 112f.

- Gruner 2008.

- Bryant 2007, p. 118f; US vs. Rudolf Adalbert Brachtel et al. (Review and Recommendations) 1948

- US vs. Rudolf Adalbert Brachtel et al. (Review and Recommendations) 1948.

- Bisky 2001.

- Benz & Distel 2005, p. 393.

- Kriegsverbrechergefängnis Landsberg

Bibliography

- Bazyler, Michael J.; Tuerkheimer, Frank M. (2014). Forgotten trials of the Holocaust. New York. ISBN 978-1-4798-0437-5. OCLC 891081620.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Benz, Wolfgang; Distel, Barbara, eds. (2005). Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. München: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-52960-3. OCLC 58602670.

- Bisky, Jens (8 March 2001). "Aus Anlass der jüngsten IM-Fälle: Warum gibt es auch nach zehn Jahren keinen Schlussstrich?: Zwei Klassen von Menschen". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Bryant, Michael (2007). "Die US-amerikanischen Militärgerichtsprozesse gegen SS-Personal, Ärzte, und Kapos des KZ Dachau 1945–1948". In Sigel, Robert; Eiber, Ludwig (eds.). Dachauer Prozesse: NS-Verbrechen vor amerikanischen Militärgerichten in Dachau 1945–48; Verfahren, Ergebnisse, Nachwirkungen. Göttingen: Wallstein. pp. 109–125. ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2. OCLC 181090319.

- Bryant, Michael S. (2020). Nazi Crimes and Their Punishment. Indianapolis: Hackett. ISBN 978-1-62466-899-9. OCLC 1141984744.

- Form, Wolfgang; Bryant, Michael S. (2011). "Victim Nationality in US and British Military Trials: Hadamar, Dachau, Belsen". In Bardgett, Suzanne; Cesarani, David; Reinisch, Jessice; Steinert, Johannes-Dieter (eds.). Justice, politics and memory in Europe after the Second World War. London: Vallentine Mitchell. pp. 19–42. ISBN 978-0-85303-942-6. OCLC 707230488.

- Frei, Norbert (2003). Vergangenheitspolitik: die Anfänge der Bundesrepublik und die NS-Vergangenheit. München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. ISBN 978-3-423-30720-8. OCLC 51308487.

- Freund, Florian (2001). "Der Dachauer Mauthausenprozess". Jahrbuch 2001 (PDF). Wien: Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes. pp. 35–66. ISBN 978-3-901142-45-1.

- Greene, Joshua (2003). Justice at Dachau. The trials of an American prosecutor (1st ed.). New York: Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0-7679-0879-5. OCLC 50280024.

- Greiser, Katrin (2007). "Die Dachauer Buchenwaldprozesse – Anspruch und Wirklichkeit – Anspruch und Wirkung". In Sigel, Robert; Eiber, Ludwig (eds.). Dachauer Prozesse: NS-Verbrechen vor amerikanischen Militärgerichten in Dachau 1945–48; Verfahren, Ergebnisse, Nachwirkungen. Göttingen: Wallstein. pp. 160–173. ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2. OCLC 181090319.

- Gruner, Martin (2008). Verurteilt in Dachau. Der Prozess gegen den KZ-Kommandanten Alex Piorkowski vor einem US-Militärgericht. Augsburg: Wißner-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89639-650-1. OCLC 316137019.

- Hartmann, Christian (2010). Wehrmacht im Ostkrieg Front und militärisches Hinterland 1941/42 (2 ed.). München. ISBN 978-3-486-70225-5. OCLC 658236747.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- Klee, Ernst (2007). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch. ISBN 978-3-596-16048-8. OCLC 70913054.

- Lessing, Holger (1993). Der erste Dachauer Prozess (1945/46) (1 ed.). Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 978-3-7890-2933-2. OCLC 30128314.

- Sigel, Robert; Eiber, Ludwig, eds. (2007). Dachauer Prozesse: NS-Verbrechen vor amerikanischen Militärgerichten in Dachau 1945–48; Verfahren, Ergebnisse, Nachwirkungen. Göttingen: Wallstein. ISBN 978-3-8353-0167-2. OCLC 181090319.

- Sigel, Robert (1992). Im Interesse der Gerechtigkeit: die Dachauer Kriegsverbrecherprozesse 1945–1948. Frankfurt: Campus. ISBN 978-3-593-34641-0. OCLC 27100088.

- Sigel, Robert (7 August 2019). "Dachauer Kriegsverbrecherprozesse". Historisches Lexikon Bayerns. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- US vs. Martin Gottfried Weiss et al., Case no. 000-50-2 (Office of the Judge Advocate, US Army War Crimes Group 1945-12-13).

- US vs. Rudolf Adalbert Brachtel et al. (Review and Recommendations), Case No. 000-50-3-103 (Deputy Judge Advocate's Office, US Army War Crimes Group 1948-02-26).

- Wilmes, Anette (25 January 2001). "Vor 50 Jahren: Entscheidung. Begnadigung der Nürnberger Kriegsverbrecher". Annette Wilmes. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Zámečník, Stanislav (2007). Das war Dachau. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch. ISBN 978-3-596-17228-3. OCLC 123018900.

External links

- Kriegsverbrechergefängnis Landsberg (in German)

- Dachau Concentration Camp Trial, archived from the original, 25 April 2012

- US vs. Alex Piorkowski et al. – Case No. 000-50-2-23 Recommendations (PDF; 2.1 MB)