Daichi Sokei

Daichi Sokei (大智祖継) (1290–1366) was a Japanese Sōtō Zen monk famous for his Buddhist poetry who lived during the late Kamakura period and early Muromachi period. According to Steven Heine, a Buddhist studies professor, "Daichi is unique in being considered one of the great medieval Zen poets during an era when Rinzai monks, who were mainly located in Kyoto or Kamakura, clearly dominated the composition of verse."[1]

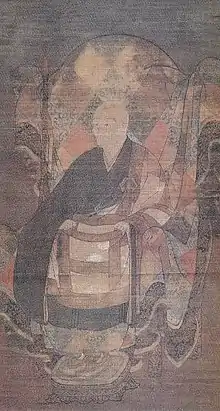

Painting on silk of Daichi Sokei dating from the Muromachi Period; from the temple Kakurinji in Kanazawa and now held at the Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of Art | |

| Title | Zen Master |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1290 |

| Died | 1366 |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Sōtō |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Kangan Giin Keizan Jōkin Meihō Sotetsu Gulin Qingmao |

| Predecessor | Meihō Sotetsu |

Biography

He was originally a disciple of one of Eihei Dōgen's students Kangan Giin, but after Giin's death he practiced under Keizan Jōkin for seven years. He also traveled to China in 1314 and remained there until 1324; his stay out of Japan was unintentionally extended when he was shipwrecked in Korea on his return journey, preventing him from actually returning until 1325.[2] Upon returning to Japan, he received dharma transmission under Keizan's disciple Meihō Sotetsu.[3] He is considered to be part of the Wanshi-ha poetry movement based on the writing style of the Sōtō monk-poet Hongzhi Zhengjue. While in China, Daichi studied under the poet Gulin Qingmao (Japanese: 古林清茂; rōmaji: Kurin Seimo).[1]

His kanbun poetry often praises the teaching of Eihei Dōgen, especially Dōgen's Shōbōgenzō. For example, when he was able to obtain a copy of the Shōbōgenzō despite living in Kyushu, hundreds of kilometers from Dōgen's home temple Eiheiji, he wrote,

The enlightened mind expressed in The Treasury of the True Dharma Eye,

Teaches us the innermost thought of the past sixty Zen ancestors.

A mythical path stemming from Eiheiji Zen temple reaches my remote village,

Where I see anew an ethereal mist rising from among remarkable shoots.[1]

A poem entitled Rai Yōkō Kaisantō indicates that sometime before the year 1340, Daichi visited the temple Yōkōji (永興寺) that had been founded by Dōgen's student Senne in Kyoto (not the same Yōkōji that Keizan founded on the Noto Peninsula, which uses the characters 永光寺), but he described the temple as already being in a state of decline by that time.[4]

On Practicing Throughout The Day (Japanese: 十二時法語; rōmaji: Jūniji-hōgo) is one of the few pieces of writing by Daichi Sokei available in full in English. In it, Daichi lays out instructions for lay people to practice with monks, giving details on how to behave during each hour of the day. According to Shōhaku Okumura, a translator of the text and a Sōtō Zen priest himself, Sokei stresses the importance of maintaining concentration in each moment of the day, which he equates with awakening itself. For example, Sokei, writes, "When you have breakfast, just attend fully to the gruel with both body and mind...This is called clarifying the time of gruel and realizing the mind of gruel. At this time, you have a pure realization of the mind of the buddha-ancestors" In Okumura's footnotes on the text, he writes, "Each activity [that Sokei describes] is not a step, means, or preparation for other things; rather each step should be completed in the moment."[3]

References

- Heine, Steven (2020), Flowers Blooming on a Withered Tree: Giun's Verse Comments on Dogen's Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, Oxford University Press, pp. 15, 202, ISBN 9780190941369

- Bodiford, William M. (1993), Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, University of Hawaii Press, p. 248, ISBN 0-8248-1482-7

- Sokei, Daichi (2011), "Jūniji-hōgo: On Practicing Throughout The Day", in Sōtō Zen International Center (ed.), Sōtō Zen: An Introduction to Zazen, translated by Okumura, Shohaku, Sotoshu Shumucho, pp. 93–98

- Bodiford, William M. (1993), Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 46, 231–232, ISBN 0-8248-1482-7