Daijosai

The Daijō-sai (大嘗祭) is a special religious service conducted in November after the enthronement, in which the Emperor of Japan gives thanks for peace of mind and a rich harvest to the solar deity Amaterasu (天照大神) and her associated deities, and pray for Japan and its citizens. From a Shinto viewpoint, the emperor is believed to be united with the deity Amaterasu in a unique way and share in her divinity. In general, the Daijosai is considered as a kind of thanksgiving harvest festival, in the same way as Niiname-sai (新嘗祭) is conducted annually on 23 November, a public holiday of Labor Thanksgiving Day. However, in the year the Daijō-sai is held, the Niiname-sai (新嘗祭) is not held.[1]

| Daijosai 大嘗祭 | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) .jpg.webp) Top: Daijō-sai of Reiwa (Imperial Palace East Garden) Bottom: The Daijō-sai of Emperor Akihito in 1990 | |

| Genre | |

| Frequency |

|

| Venue | Daijokyu (Sukiden, Yukiden, and Kairyuden) |

| Location(s) | Residence of the Emperor of Japan(Has changed over the ages, currently Tokyo Imperial Palace) |

| Country | Japan |

| Inaugurated | It is rooted in farming rituals, and its original form is thought to be from around the Yayoi period, and the current scale and style are from the era of Tenmu and Jito. Around (7th century) |

| Previous event | 2019 (2022) 14 and 15 November |

| Next event | Upon a new Emperor succeeding to the Chrysanthemum Throne |

| Attendance | Approximately 730 people in total |

| Activity | A ceremony in which the newly enthroned emperor makes an offering to the gods of new grain offered from the east and west of Japan, and eats it himself to pray for a bountiful harvest, peace of mind during his reign, and the well-being of the nation and its people, according to Shinto. |

| Patron(s) | Japanese government |

| Organised by | Imperial Household Agency |

| Website | 宮内庁 |

The emperor and empress both perform the Daijosai ceremony in November after ascending the throne in a partly televised ceremony and since 2019 it is a live-streamed event. It is only performed once during their reign. Akihito performed it in November 1990 and Naruhito on 14 November 2019. The emperor offers gifts such as rice, kelp, millet and abalone to the gods. Then he reads an appeal to the gods and eats the offering and prays. The emperor and empress perform the rites separately. It takes about 3 hours. Over 500 people are present including the Prime Minister, government officials, representatives of state and private sector firms, society groups and members of the press. It originates as a Shinto rite from at least the 7th century. It is held as a private event by the Imperial Household so that it does not violate the separation of church and state. A special complex with over 30 structures (大嘗宮, daijōkyū) is built for the event. Afterward, they are accessible to the public for a few weeks and then dismantled. In 1990, the ritual cost more than 2.7 billion yen ($24.7 million).[2]

The Daijosai is a highly secret ritual that very few people know the full details of, this has led to controversy with some claiming it violates Women's rights,[3] and Article 20 of the Japanese constitution, which separates religion from government.[4]

Overview

In general, like the Niinamesai, the Daijosai is understood as an autumn festival of thanksgiving for the harvest. In fact, there are some similarities in the ritual schedule, and in the same year that Omame-sai is held, Niinamesai is not held. Before the Daiho Ritsuryo, "Otamesai" and "Shinamesai" were different names for the same ritual.

Since rituals are a secret affair, there have been various discussions about their contents. In the past, the theory of the "bedding over the bedding" advocated by Orikuchi Nobuo, that is, a ritual in which the emperor's spirit is put on the new emperor by reproducing the scene of Amagasaki in Japanese mythology, was proposed. The hypothesis was supported, and research was conducted in the form of development or modification of the hypothesis.[5]。In 1983, Okada Seiji sharply criticized this theory, advocating the rite of holy matrimony, and it gained a certain amount of support in the Japanese historical community.[6]

However, from 1989 to 1990, Shoji Okada published an essay that rejected both the "makuro-covered bedding (真床覆衾)" theory and the sacred marriage rite theory.[7]。According to Okada Shoji's theory, the Omamesai is a simple ritual in which the new emperor welcomes Amaterasu for the first time, centering on the offering of sacred food and a communal meal ritual.[7]。This view, that the emperor enjoys the divine authority of Amaterasu by enhancing the divine authority of Amaterasu, is consistent with the common view before Orikuchi, as well as the view of Middle Ages lords such as Ichijō Kaneyoshi.[7]。Okada Shoji also noted that the feast of Omameshi-Matsuri is not only to give thanks for the rice harvest, but also for millet, which was an emergency food for the common people in ancient times, and that Omameshi-Matsuri is a prayer for the stability of the people and the prevention of natural disasters that would disturb agriculture. He opined that it is "a prayer for the calming of nature in mountains and rivers" and "the nation's highest ritual to pray for the peace of the nation and its people".[8]

Later, Masahiro Nishimoto introduced a newly published anecdote from "Nairashiki" and its examination has resulted in the almost complete rejection of both the "mashitoko-covering-bedding" theory and the sacred marriage rite theory by the Japanese historical community.[9]

History

The form of the tamesai (= new tasting rice) ceremony was established in the 7th century during the reign of Empress Kōgyoku, but at that time there was still no distinction between the regular tamesai (= new tasting rice) ceremony and the Jinsō tamesai ceremony. The first time that a ceremony of a different scale was held in addition to the regular Omamesai was during the reign of Emperor Tenmu.[10]。However, at that time, it was not yet a once-in-a-generation event associated with accession to the throne, but was held several times during the reign.[11] With the establishment of the Ritsuryo system, the festival was named the "Shansho Otamesai" as a once-in-a-generation ritual, and the details of the ceremony, including the ritual procedures, were also established. Of the ceremonial rites stipulated in the Engi-Shiki, only the Omamesai was designated as a "daisai" (ritual of the Great Taste of Rice). The name "Dajo-e" was derived from the fact that a three-day long festival was held after the tasting of the first taro.[12]。Later on, the ordinary tamesai (= new tamesai) was sometimes referred to as "the annual tamesai" and the practice of tamesai as "the tamesai of every generation". Originally, in the Chronicles of Japan, the tame and the new tame were neither referred to as "festival" nor "assembly. They are simply described as "ote" and "shintame. In the Nara period (710–794), they were called "Otame-kai" and "Shintame-kai," and in the Heian period (794–1185), they were officially called "Otamesai" and "Shintamesai," but in most diaries, "Otamesai" and "Shintame-kai" are used. This indicates that one of the most important components of the tasting of taro and the tasting of shin-tame was the "meeting".[13]。

However, in the late Muromachi Period and the Sengoku Period, the shogunate was weakened by warfare, and the imperial court became impoverished, which hampered the imperial rites. The tame festival was held until 1466, the first year of Emperor Go-Tsuchimikado's reign, but after the outbreak of the Onin War the following year, it became impossible to collect temporary expenses (tame-kaiyaku). For more than a year, he was forced to abort. In August 1545, Emperor Go-Nara wrote a decree to the Ise Jingu Shrine to pray for the restoration of the imperial family and the people, and at the same time to apologize for the inability to hold the tame-matsuri ceremony.[14]。

After domestic stability was restored by the Oryoho regime and the Tokugawa Shogunate, there was a period of time when the tasting of the tithes was not practiced, but Emperor Reigen was intent on reviving the imperial rites, and first restored the rite of the Crown Prince Asahito in 1683, the first time in approximately 340 years. In 1684, the Emperor wished to transfer the throne to the Crown Prince and to restore the Great Tamesai Ceremony, and had the Shogunate negotiate with the Emperor. At that time, he explained in the form of a precedent that the tame-matsuri should be held upon the accession of the crown prince to the throne. The Shogunate, which had been at loggerheads with the Imperial Court due to the Murasaki Incident and other events, was reluctant to request the same ceremonial protocol as in the previous case (when Emperor Reigen ascended to the throne), but after negotiations, the reestablishment was approved on condition that the entire budget for the succession to the throne be paid in the same amount as in the previous case. In 1687, the emperor abdicated and the crown prince acceded to the throne (Emperor Higashiyama), and the Great Taste of Rice Ceremony was held for the first time in 221 years. However, due to budgetary constraints, the reconstruction was a shortened version at this point.。

When the next generation Emperor Nakamikado succeeded to the throne, Daijosai was not held. This is attributed to the pledge during the reign of Emperor Reigen. At the time of the succession to the throne of Emperor Sakuramachi, the imperial court initially declined the offer from the shogunate side, but eventually the imperial court side revived Niiname-no-Matsuri. There was an offer, and after negotiations between the imperial courts, the Daijosai was held again in 1738,[lower-alpha 1] three years after the succession to the throne, and after that, the Daijosai was held without interruption every time it was replaced. It came to be done.[15]

From the Nara era to the Heian era of the Heijo, the site for the Taimae Ceremony was the Ryuo-dan garden in the front yard of Chodoin, located in the southern center of the Ouchiura. The first two are the first two. After the burning down of Chodoin at the end of the Heian period, it was still built roughly on the former site of Daigoku-den, under the Ryuo-dan. During the reign of Emperor Antoku, the capital was temporarily relocated to Fukuhara-kyō and was postponed due to the death of Emperor Takakura, but was finally moved to Emperor Go-Shirakawa by the ruling of Emperor Shirakawa. The ceremony was held in 1182 (Juei 1), but due to the current circumstances, including the Genpei War (Genpei War), it was held at Shikikakuden. [16]。When Emperor Higashiyama was reestablished, perhaps because the site of Daigoku-den was not yet clear, he followed the precedent set by Emperor Antoku and used the forecourt of Shikikakuden, leading to the Meiji period. In the Meiji period (1868–1912), the accession ceremony was held in Shikikinden, but the tamesai ceremony was held at the Fukiage Palace in Tokyo. During the Taishō and Shōwa eras, the former Sentō Gosho in the Omiya Gosho in Kyoto was used under the "Togoku Order". Since the Heisei era, the ceremony has again been held at the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

- During the Edo period, the Emperor decided to follow the old ways and forbid Buddhism Sangha Bhikkhunī to enter the palace and remove the title of successive emperors. Reigen and Regent Ichijō Fuyūketsu (Kaneteru), who opposed the Emperor's brother, Prince Gyōjo, and Minister of the Left Konoe Motohiro Hui and others were at odds with each other. This movement to exclude Buddhism was reinforced each time the new emperor held the first Grand Tasting Ceremony, in conjunction with the rise of Kokugaku and the theory of the reverence for the emperor, which led to criticism of the long-established court practice of shimbutsu shugō and to debates about the pros and cons of the exclusion of Buddhism and its attendant enthronement ceremony. Some believe that it developed into a distant cause of the Separation of Shinto and Buddhism at the Imperial Court in the Meiji period.[17]。

- In the Ōei Taimeikai (Records of the Great Tasting Ceremony) written by Ichijō Tsunetsugu in the Muromachi period, it is written that "The national event is the Taimeikai, and the event is no more than a Shinto meal", and in the Eiwa Taimeikai, it is written that only the emperor and his attendants may enter the temple (Taimekiya). However, in the historical background of the period when young emperors between the ages of two and seven continued from Emperor Horikawa to Emperor Antoku and Emperor Go-Toba, we can see "Nigyo" and "Gode" in Oe Masafusa's "Eke Yadai" and "Enkei Datame Ki" and "Go-Toba" in the "Enkei Datame Ki" and "Go-Toba". If the emperor was 10 years of age or older (an adult who had reached the age of full age), as described in the "Oei Taiteki," the emperor himself offered the "Nigyo" service, and if the emperor was 9 years of age or younger, the regent offered the "Gode" service. In addition, a few days before the Omame-sai, a preliminary ritual of the offering of the offering of the offering of the offering of the food to the gods is held.[18]

- The ceremonies related to the coronation ceremony were designated as national events, while the ceremonies related to the Daijosai were designated as imperial events. It is often misunderstood that "imperial event" here does not mean "private event of the imperial family" but "public event of the imperial family". The budget for Daijosai is extraordinary, other than the usual court fees. According to the government announcement (final answer) at that time, the reason why Daijosai was not regarded as "state affairs" is that the emperor's "state affairs" under the Constitution of Japan requires "advice and approval of the Cabinet". This is because the Daijosai, which is a traditional ritual of the imperial family, does not fall under the category of "state affairs."

Details

First, two special rice paddies (斎田, saiden) are chosen and purified by elaborate Shinto purification rites. The families of the farmers who are to cultivate the rice in these paddies must be in perfect health. Once the rice is grown and harvested, it is stored in a special Shinto shrine as its go-shintai (御神体), the embodiment of a kami or divine force. Each kernel must be whole and unbroken, and is individually polished before it is boiled. Some sake is also brewed from this rice. The two sets of rice seedlings now blessed each come from the western and eastern prefectures of Japan, and the chosen rice from these is assigned from a designated prefecture each in the west and east of the country, respectively.

Two thatched roof two-room huts (悠紀殿 yukiden, lit. East-region hall) and (主基殿 sukiden, lit. West-region hall) are built within a corresponding special enclosure, using a native Japanese building style that predates and is thus devoid of all Chinese cultural influence. The Yukiden and Sukiden represent the east and west halves of Japan, respectively. Each hall is divided into two rooms, with one room containing a large couch made of tatami mats at its center, in addition to a seat for the emperor and a place to enshrine the kami; the second is used by musicians. All furniture and household items also preserve these earliest, and thus most purely Japanese forms: e.g., all pottery objects are fired but unglazed. These two structures represent the house of the preceding emperor and that of the new emperor. In earlier times, when the head of a household died his house was burned; before the founding of Kyoto, whenever an emperor died his entire capital city was burned as a rite of purification. As in the earlier ceremony, the two houses represent housing styles from western and eastern parts of Japan. Since 1990, the temporary enclosure is located at the eastern grounds of the Imperial Palace complex.

Ceremony day

This ceremony, also known as O-ni-e-matsuri (大嘗祭) and O-name-matsuri (大嘗まつり (大嘗祭) is marked as an Imperial court ritual performed by the Emperor of Japan upon his succession to the throne, and is an Imperial Household Ritual. In olden times, it was also called "Ohonimatsuri" or "Ohonamatsuri".[19] In modern times, however, it is read phonetically as "Daijosai".[20]

After a ritual bath on the night of the ceremony, the emperor is dressed entirely in the white silk dress of a Shinto priest, but with a special long train. Surrounded by courtiers (some of them carrying torches), the emperor solemnly enters first the enclosure and then each of these huts in turn and performs the same ritual—from 6:30 to 9:30 pm in the first, and in the second from 12:30 to 3:30 am on the same night. A mat is unrolled before him and then rolled up again as he walks, so that his feet never touch the ground. A special umbrella is held over the sovereign's head, in which the shade hangs from a phoenix carved at the end of the pole and prevents any defilement of his sacred person coming from the air above him. Kneeling on a mat situated to face the Grand Shrine of Ise, as the traditional gagaku court music is played by the court orchestra the emperor makes an offering of the sacred rice, the sake made from this rice, millet, fish and a variety of other foods from both the land and the sea to the kami, the offerings of east and west being made in their corresponding halls. Then he eats some of this sacred rice himself, as an act of divine communion that consummates his singular unity with Amaterasu-ōmikami, thus making him (in Shinto tradition) the intermediary between Amaterasu and the Japanese people. The significance of the offerings and the ceremonial dinner of the tithes is as an act of thanksgiving to Amaterasu and Tenjin Jigami, the ancestors of the Emperor, and as a prayer for the nation and its people's peace and good harvests in his reign.[21] He then prays to the gods in gratitude, and then leaves the huts so that the Empress may then performs the same ceremonial protocol there before departing the complex.[22]

Controversies of the Daijosai

Relationship to the Constitution's principle of separation of church and state

Some members of the public, including Christian and Buddhist officials, are of the opinion that government spending on the Omameshi-Matsuri and the participation of prefectural governors in the Omameshi-Matsuri are unconstitutional due the Constitution's principle of a separation of church and state.[23][24] Some Constitutional lawsuits have been filed from the viewpoint of this separation of church and state, but all the lawsuits have been dismissed. These plaintiffs were defeated due to the judgment that the expenditure of state funds did not disadvantage the plaintiffs and that the governors' attendance did not violate the separation of church and state in light of the purpose-effect standard of the separation of church and state[25]

According to the decision of the Japanese Supreme Court in July 1977, "The separation of church and state in the Constitution does not mean that the state is not allowed to have relations with religion at all, but that it is not allowed when it is deemed to exceed reasonable limits. It does not allow the state to have relations with religion at all, but only in cases where such relations are deemed to exceed reasonable limits." This is one of the reasons why the government has approved the expenditure of government funds for the Omameshigai.[25] However, in 1995, the Osaka High Court rejected the plaintiff's lawsuit, stating that "the tasting of the Heisei era has already been completed and the plaintiff is not disadvantaged," but in a side argument, the court pointed out that "the suspicion of a violation of the Constitution cannot be denied in general."[26]

On 10 December 2018, 241 plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against the government in the Tokyo District Court seeking an injunction to stop the government from spending money and compensation for damages on the grounds that the implementation of the "Rei (retirement)", "Sokui-no-rei (enthronement)", and "Taitei-Matsuri (tasting of rice)" ceremonies following the abdication of Emperor Akihito and accession of Crown Prince Naruhito, under the provisions of the Special Act on the Imperial Household Law concerning the Abdication of the Emperor, violates the Constitutional provision stipulating separation of church and state.

Opinions of the Emperor and members of the Imperial Family

Emperor Shōwa reportedly told his aides that they should save and accumulate the money for the inner court.[27]。

Nobuhito, Prince Takamatsu said, "Why don't we just do it at the Three Palace Sanctuaries, where the annual Niinamesai is held, without building a large daijokyu," he said.[28]。

Prince Fumihito Akishino has proposed a plan similar to that of Prince Takamatsu, that the expenses for the Daijosai be paid from the national budget, and that they be covered by the expenses of the Imperial Court by utilizing the Shinkaden, a smaller building near the Three Palace Sanctuaries used for the ordinary Niinamesai.[29][30]。

Budget, construction, and changes in the Reiwa era

The government and the Imperial Household Agency followed the precedent of the Heisei era and spent money from the national budget, but changed the roof of the daijokyu, which had previously been thatching, to shingles, and reduced expenses by building some facilities such as the kashiwaya (kitchens for the offerings of food to be prepared in) in reinforced concrete under the premise that it was acceptable as long as it didn't alter the rituals or serve as an impediment to them. The original planned construction cost of the daijokyu was 1.97 billion yen,[31] actually in 2019 (the first year of the 2025 Shimizu Corporation won the bid for 957 million yen, 60% of the planned price, in a competitive bidding process held at the Imperial Household Agency on 10 May 2019.

On the occasion of the Heisei Daijosai, the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace were completely closed as an anti-terrorist measure during the construction of the Imperial Palace, due to the active anti-emperor extremist movement at the time, and once completed, the main buildings were covered with large protective tents of extremely solid construction, and four 2,500-liter Fire prevention tanks and fire pumps were installed in four locations. In contrast, the East Palace Garden was not closed during the 2021 Daijosai, and the construction of the daijokyu was open for all to see, in order to "deepen the public's understanding of the expenditure of national funds for the Daijosai."[32]。It was also decided that after the Daijosai, the daijokyu would remain open to the public as it had been during construction, and that materials would be reused after dismantling.

See also

Gallery

- Daijosai

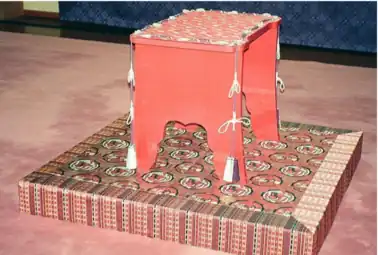

Scale model of the Heisei era daijokyu, built in 1990

Scale model of the Heisei era daijokyu, built in 1990 Prince Nashimoto Morimasa at Emperor Taishō's ceremony

Prince Nashimoto Morimasa at Emperor Taishō's ceremony The daijokyu, where the festival was held, depicted on a postage stamp commemorating the Emperor Showa's accession and Daijosai.

The daijokyu, where the festival was held, depicted on a postage stamp commemorating the Emperor Showa's accession and Daijosai. A table in red lacquer for holding the sword and jewel of the Imperial regalia

A table in red lacquer for holding the sword and jewel of the Imperial regalia Imperial throne

Imperial throne

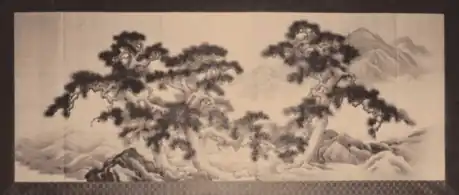

Traditional dancing of eastern Japan, performed during the rituals in the Yukiden.

Traditional dancing of eastern Japan, performed during the rituals in the Yukiden. Traditional dancing of western Japan, performed during the rituals in the Sukiden.

Traditional dancing of western Japan, performed during the rituals in the Sukiden. Kinshitsu Kakusa (from the Showa Tairekiroku)

Kinshitsu Kakusa (from the Showa Tairekiroku)

Notes

- From the following year, the Shinmame Festival was also held every year.

References

- Tsunetada Mayumi [in Japanese] (2019). 大嘗祭 [Enthronement of the Japanese emperor]. Chikuma Shinsyo. Chikuma Shobō.

- Yukihiro Enomoto. "Japan emperor performs centuries-old succession rite". Nikkei Asian Review. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "Daijosai ritual: Why Japanese Emperor Naruhito spent a night with the sun goddess". The Indian Express. 21 November 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- Jones, Colin P. A. (23 December 2019). "The Reiwa Daijosai: Pomp, circumstance and litigation". The Japan Times. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- 小倉・山口(2018年), p. 21.

- 小倉・山口(2018年), p. 22.

- 小倉・山口(2018年), p. 23.

- 岡田荘司ほか『大嘗祭』國學院大學博物館(2019)

- 小倉・山口(2018年), p. 24.

- "大嘗祭|皇位継承式典 平成から令和へ 新時代の幕開け". NHK NEWS WEB. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- 斎忌(悠紀国)と次(主基国)とその卜定について史上初めて言及されるのは『日本書紀』巻第29の天武天皇5年の相嘗祭と新嘗祭に関してであるが、即位後最初の大嘗祭は天武天皇2年に既に行われている。

- 小山田義夫「大嘗会役小考」(『一国平均役と中世社会』(岩田書院、2008年) ISBN 978-4-87294-504-1(原論文は1976年))

- 『神社のいろは用語集 祭祀編』、神社本庁監修 p.271 ISBN 978-4-594-07193-6

- 岡田荘司、『大嘗祭と古代の祭祀』あとがきに続く「大嘗祭の年表」p.3 ISBN 978-4-642-08350-8

- 古相, pp. 74–75.

- 加瀬, pp. 58–59.

- 山口和夫「神仏習合と近世天皇の祭祀」(初出:島薗進 他編『シリーズ日本人と宗教1 将軍と天皇』(春秋社、2014年)/所収:山口『近世日本政治史と朝廷』(吉川弘文館、2017年) ISBN 978-4-642-03480-7 P352-356)

- 安江和宣『大嘗祭神饌御供進儀の研究』p.25

- 井原頼明『皇室事典』冨山房、1943年、8ページ

- ご即位・立太子・成年に関する用語 宮内庁ホームページ(2019年6月4日閲覧)。

- 鎌田, p. 178.

- Schoenberger, Karl (23 November 1990). "Akihito in Final Ritual of Passage". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- 金子勝『日本国憲法の原理と「国家改造構想」』1994年

- "全国220人:「大嘗祭は違憲」12月10日に提訴へ". 毎日新聞. 30 November 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- 平成の御代替わりに伴う儀式に関する最高裁判決

- 即位の礼・大嘗祭国費支出差止等請求控訴事件 裁判所

- "(社説)即位の礼 前例踏襲が残した課題". 朝日新聞デジタル. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "続く皇室からの発信 雅子さまに触れなかった意図は?". wezzy. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- "私費で賄う大嘗祭、秋篠宮さま自ら提案 既存の神殿活用". 朝日新聞デジタル. 25 December 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- "「"貯金"のできる内廷費でやりたい」が皇族がたの本音? 27億円の国費を投じる大嘗祭と、"国事行為"たる即位の礼が持つ意味". wezzy. 10 January 2019. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- 多田晃子 (21 December 2018). "大嘗宮の設営費、4億円増え19億円に 儀式後には解体". 朝日新聞デジタル. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- INC, SANKEI DIGITAL (26 July 2019). "大嘗宮建設中に東御苑公開 大嘗祭へ理解促す 警備に工夫も". 産経ニュース (in Japanese). Retrieved 1 September 2019.

Bibliography

- 田中初夫『践祚大嘗祭』木耳社、1983年

- 岡田精司編『大嘗祭と新嘗』学生社、1979年、復刊1989年(特に折口信夫「大嘗祭の本義」)

- 折口信夫『古代研究II 祝詞の発生』中公クラシックス、2003年。上記を収録

- 『古代研究III 民俗学篇3』角川ソフィア文庫、2017年。上記を収録

- 『大嘗祭の本義 民俗学からみた大嘗祭』森田勇造現代語訳、三和書籍、2019年

- 吉野裕子『天皇の祭り』講談社学術文庫、2000年

- 岡田荘司『大嘗祭と古代の祭祀』 吉川弘文館、2019年3月 ISBN 978-4-642-08350-8

- 加瀬直弥 (25 July 2019). "中世の大嘗祭". 季刊 悠久. 東京都千代田区: おうふう (158). ISSN 0388-6433.

- 福羽美静 (1895). 硯堂叢書. 八尾書店.

- 鈴木暢幸、小松悦二 (1915). 御即位式大典録 後編. 御即位大典紀念会.

- 大礼記録編纂委員会 (1931). 昭和大礼要録. 内閣印刷局.

- 鎌田純一 (2003). 即位禮・大嘗祭 平成大禮要話. 錦正社. ISBN 4-7646-0262-8.

- 加茂正典 (25 July 2019). "古代の大嘗祭". 季刊 悠久. 東京都千代田区: おうふう (158). ISSN 0388-6433.

- 小倉慈司・山口輝臣 (2018年). 天皇の歴史9:天皇と宗教. 講談社学術文庫. 講談社. ISBN 978-4065126714.

- 武田秀章 (25 July 2019). "近現代の大嘗祭". 季刊 悠久. 東京都千代田区: おうふう (158). ISSN 0388-6433.

- 古相正美 (25 July 2019). "大嘗祭の中絶と復興". 季刊 悠久. 東京都千代田区: おうふう (158). ISSN 0388-6433.

- 真弓常忠 (2019). 大嘗祭. ちくま学芸文庫. ISBN 978-4-480-09919-8.

- 真弓常忠 (April 2019). 大嘗祭の世界 新版. 学生社. ISBN 978-4-311-80128-0.

- 安江和宣『大嘗祭神饌御供進儀の研究』神社新報社、2019年5月。ISBN 978-4-908128-23-3

External links

- "皇位の継承に係わる儀式等(大嘗祭を中心に)について(皇室典範に関する有識者会議(第8回)配付資料)" (PDF). 首相官邸. 2005. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)