Daniel Kinnear Clark

Daniel Kinnear Clark (17 July 1822 – 22 January 1896) was a Scottish consulting railway engineer. He served as Locomotive Superintendent to the Great North of Scotland Railway between 1853 and 1855, and also wrote comprehensive books on railway engineering matters.

Daniel Kinnear Clark | |

|---|---|

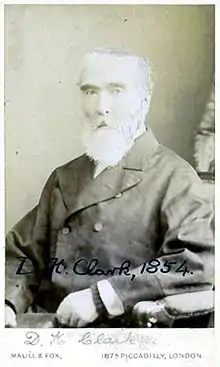

Daniel Kinnear Clark, 1854 | |

| Born | 17 July 1822 |

| Died | 22 January 1896 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Discipline | Railway mechanical engineer |

| Institutions | Institution of Civil Engineers |

| Employer(s) | Great North of Scotland Railway |

Biography

Clark was born at Edinburgh on 17 July 1822. He served an apprenticeship with Thomas Edgington & Son, a Glasgow ironworks. He then worked for another private firm, followed by the North British Railway. In 1851, he set up as a consulting engineer in London; he was 30 years old.[1][2] He became a Member of the Institute of Mechanical Engineers in 1854.[1]

The Great North of Scotland Railway (GNoSR) had been established in 1845 with the aim of building a railway to connect Aberdeen with Inverness.[3] Although authorised in 1846, construction did not begin until 1852, with the first section of line being opened in 1854.[4] While the line was still under construction, it became necessary to consider the provision of locomotives in time for the opening. Workshops at Kittybrewster for the repair of locomotives were under construction, and Clark was appointed Superintendent of the Locomotive Works in October 1853. For the opening of the line, he designed two basically similar classes of 2-4-0 tender locomotives, one with driving wheels 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 m) in diameter for passenger service, and the other, for goods trains, having 5-foot (1.5 m) driving wheels. Seven passenger engines and five goods were ordered from William Fairbairn & Sons of Manchester,[1][2] since Kittybrewster Works was not intended for locomotive construction: no new engines were built there until 1887.[5] The first section of the line (from Kittybrewster to Huntly) was opened for traffic on 12 September 1854,[6] but by October only five of the passenger engines had been delivered, and just two more had arrived by the time of his resignation; the five goods engines arrived a few months later.[7]

At his appointment, the GNoSR had made it a condition that Clark should live in Aberdeen, to be close to his duties; but he felt that living in northern Scotland 'would be inimical to his advancement in his profession', preferring to work through an assistant based at Kittybrewster. A dispute with the GNoSR board ensued, and Clark resigned in March 1855.[1][8] His replacement, J. F. Ruthven, had been works foreman under Clark. He also had a short tenure, and when he in turn resigned in May 1857, he too became a consultant, and often worked with Clark.[9]

Clark returned to consultancy, and patented a device for preventing smoke from being emitted when coal was burned in locomotive fireboxes.[1] The primary feature of this device was a series of air inlets in the firebox sides, air being forced in by steam jets when the regulator was closed.[10][11] It was invented in 1857, tried out by the North London Railway and the Eastern Counties Railway, and following further trials in 1858 by Clark's former employer, the GNoSR, was adopted in 1859 as a standard fitting by the latter railway.[10] It was used on all GNoSR locomotives built during the terms of office of Clark's successors Ruthven (1855–1857) and William Cowan (1857–1883),[12][11] and was still being fitted to new engines as late as 1890 by Cowan's successor James Manson, although in modified form.[13][14]

Clark wrote several books including the two-volume Railway Machinery, which was considered an authoritative text when it was published in 1855.[8] He became a Member of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 27 January 1863.[1]

Clark died in London on 22 January 1896.[1]

Bibliography

- Clark, D.K. (1855). Railway Machinery, volume 1. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.

- —— (1855). Railway Machinery, volume 2. Glasgow: Blackie and Son.

- —— (1856). Railway Locomotives, volume 1.

- —— (1860). Railway Locomotives, volume 2.

- —— (1860). Recent practice in the locomotive engine. Blackie and Son.

- —— (1884) [1877]. Manual of Rules for Mechanical Engineers.

- —— (1880). Fuel, its combustion and economy.

- —— (1878). Tramways and their Construction and Working, volume 1. ; 2nd edition online

- —— (1881). Tramways and their Construction and Working, volume 2.

- —— (1887). The Construction of Roads and Streets.

- —— (1893). The Steam Engine, volume 1. Blackie & Son.

- —— (1893). The Steam Engine, volume 2.

Notes

- Marshall 1978, p. 52.

- Vallance 1991, p. 144.

- Vallance 1991, pp. 13–14.

- Vallance 1991, p. 15,21–24.

- Vallance 1991, p. 156.

- Vallance 1991, pp. 24, 199.

- Vallance 1991, pp. 144–145.

- Vallance 1991, p. 145.

- Vallance 1991, p. 146.

- Ahrons 1987, p. 134.

- Boddy et al. 1968, p. 57.

- Vallance 1991, pp. 146, 147.

- Ahrons 1987, p. 273.

- Boddy et al. 1968, pp. 53, 55.

References

- Ahrons, E.L. (1987) [1927]. The British Steam Railway Locomotive 1825–1925. London: Bracken Books. ISBN 1-85170-103-6.

- Boddy, M.G.; Brown, W.A.; Fry, E.V.; Hennigan, W.; Manners, F.; Neve, E.; Tee, D.F.; Yeadon, W.B. (April 1968). Fry, E.V. (ed.). Part 4: Tender Engines – Classes D25 to E7. Locomotives of the L.N.E.R. Kenilworth: RCTS. ISBN 0-901115-01-0.

- Marshall, John (1978). A Biographical Dictionary of Railway Engineers. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7489-3.

- Vallance, H.A. (1991) [1965]. The Great North of Scotland Railway. Nairn: David St John Thomas. ISBN 0-946537-60-7.