East Asian Yogācāra

East Asian Yogācāra refers to the traditions in East Asia which developed out of the Indian Buddhist Yogācāra (lit. "yogic practice") systems (also known as Vijñānavāda, "the doctrine of consciousness" or Cittamātra, "mind-only"). In East Asia, this school of Buddhist idealism was known by the names: "Consciousness-Only school" (traditional Chinese: 唯識宗; ; pinyin: Wéishí-zōng; Japanese pronunciation: Yuishiki-shū; Korean: 유식종) and "Dharma Characteristics school" traditional Chinese: 法相宗; ; pinyin: Fǎxiàng-zōng; Japanese pronunciation: Hossō-shū; Korean: 법상종).

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

Chinese: "Buddha" |

The 4th-century Gandharan brothers, Asaṅga and Vasubandhu, are considered the classic founders of Indian Yogacara school.[1] The East Asian branch of the tradition was founded through the work of scholars like Bodhiruci, Paramārtha, Xuanzang and his students Kuiji, Woncheuk and Dōshō.

Etymology

The term Fǎxiàng itself was first applied to this tradition by the Huayan teacher Fazang (Chinese: 法藏), who used it to characterize Consciousness Only teachings as provisional, dealing with the phenomenal appearances of the dharmas. Chinese proponents preferred the title Wéishí (唯識), meaning "Consciousness Only" (Sanskrit Vijñaptimātra).

This school may also be called Wéishí Yújiāxíng Pài (唯識瑜伽行派 "Consciousness-Only Yogācāra School") or Yǒu Zōng (有宗 "School of Existence"). Yin Shun also introduced a threefold classification for Buddhist teachings which designates this school as Xūwàng Wéishí Xì (虛妄唯識系 "False Imagination Mere Consciousness System").[2]

Characteristics

Like the parent Yogācāra school, the Consciousness-Only school teaches that understanding of reality comes from one's own mind, rather than actual empirical experience. The mind distorts reality and projects it as reality itself.[3] In keeping with Yogācāra tradition, the mind is divided into the Eight Consciousnesses and the Four Aspects of Cognition, which produce what we view as reality.

The Consciousness-Only school also maintained the Five Natures Doctrine (Chinese: 五性各別; pinyin: wǔxìng gèbié; Wade–Giles: wu-hsing ko-pieh) which brought it into doctrinal conflict with the Tiantai school in China.

History in China

Translations of Indian Yogācāra texts were first introduced to China in the early fifth century.[4] Among these was Guṇabhadra's translation of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra in four fascicles, which would also become important in the early history of Chan Buddhism. The earliest Yogacara traditions were the Dilun (Daśabhūmika) and Shelun (Mahāyānasaṃgraha) schools, which were based on Chinese translations of Indian Yogacara treatises.

The Dilun and Shelun schools followed traditional Indian Yogacara teachings along with tathāgatagarbha (i.e. buddha-nature) teachings, and as such were really hybrids of Yogācāra and tathāgatagarbha.[5] While these schools were eventually eclipsed by other Chinese Buddhist traditions, their ideas were preserved and developed by later thinkers, including the Korean monks Woncheuk (c. 613–696) and Wohnyo, and the patriarchs of the Huayan school like Zhiyan (602–668), who himself studied under Dilun and Shelun masters and Fazang (643–712).[6]

Dilun school

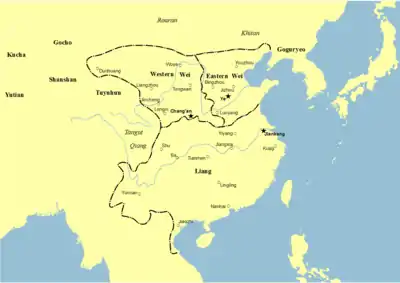

The Dilun or Daśabhūmikā school (Sanskrit. Chinese: 地論宗; pinyin di lun zong, "School of the Treatise on the Bhūmis") was a tradition that derived from the translators Bodhiruci and Ratnamati. Both translators worked on Vasubandhu's Shidijing lun (十地經論, Sanskrit: *Daśabhūmi-vyākhyāna or *Daśabhūmika-sūtra-śāstra, "Commentary on the Daśabhūmikasūtra"), producing a translation during the Northern Wei.[5]

Bodhiruci and Ratnamati ended up disagreeing on how to interpret Yogacara doctrine and thus, this tradition eventually split into northern and southern schools. During the Northern and Southern Dynasties era this was the most popular Yogacara school. The northern school followed the interpretations and teachings of Bodhiruci (6th century CE) while the southern school followed Ratnamati.[5]

According to Hans-Rudolf Kantor, one of the most important doctrinal differences and points of contention between the southern and northern Dilun schools was "the question of whether the ālaya-consciousness is constituted of both reality and purity, and is identical with the pure mind (Southern Way), or whether it comprises exclusively falsehood, and is a mind of defilements giving rise to the unreal world of sentient beings (Northern Way)."[7]

According to Daochong (道寵), a student of Bodhiruci and the main representative of the northern school, the storehouse consciousness is not ultimately real and buddha-nature is something that one acquires only after attaining Buddhahood (that is, the storehouse consciousness ceases and transforms into the buddha-nature). On the other hand, the southern school of Ratnamatiʼs student Huiguang (慧光) held that the storehouse consciousness was real and synonymous with buddha-nature, which is immanent in all sentient beings like a jewel in a trash heap. Other important figures of the southern school were Huiguangʼs disciple Fashang (法上, 495–580), and Fashangʼs disciple Jingying Huiyuan (淨影慧遠, 523–592). This school's doctrine was later passed on to the Huayan school via Zhiyan.[8]

Shelun school

During the sixth century CE, the Indian monk and translator Paramārtha (499-569) widely propagated Yogācāra teachings in China. His translations include the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra, the Madhyāntavibhāga-kārikā, the Triṃśikā-vijñaptimātratā, and the Mahāyānasaṃgraha. Paramārtha also taught widely on the principles of Consciousness Only, and developed a large following in southern China. Many monks and laypeople traveled long distances to hear his teachings, especially those on the Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[9] This tradition was known as the Shelun school (摂論宗, Shelun zong).[10]

Xuanzang's Consciousness-only school

By the time of Xuanzang (602 – 664), Yogācāra teachings had already been propagated widely in China, but there were many conflicting interpretations. At the age of 33, Xuanzang made a dangerous journey to India in order to study Buddhism there and to procure Buddhist texts for translation into Chinese.[11] This journey was later the subject of legend and eventually fictionalized as the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, a major component of East Asian popular culture from Chinese opera to Japanese television (Monkey Magic). Xuanzang spent over ten years in India traveling and studying under various Buddhist masters.[11] These masters included Śīlabhadra, the abbot of the Nālandā Mahāvihāra, who was then 106 years old.[12] Xuanzang was tutored in the Yogācāra teachings by Śīlabhadra for several years at Nālandā. Upon his return from India, Xuanzang brought with him a wagon-load of Buddhist texts, including important Yogācāra works such as the Yogācārabhūmi-śastra.[13] In total, Xuanzang had procured 657 Buddhist texts from India.[11] Upon his return to China, he was given government support and many assistants for the purpose of translating these texts into Chinese.

As an important contribution to East Asian Yogācāra, Xuanzang composed the treatise Cheng Weishi Lun, or "Discourse on the Establishment of Consciousness Only."[14] This work is framed around Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā-vijñaptimātratā, or "Thirty Verses on Consciousness Only." Xuanzang upheld Dharmapala of Nalanda's commentary on this work as being the correct one, and provided his own explanations of these as well as other views in the Cheng Weishi Lun.[14] This work was composed at the behest of Xuanzang's disciple Kuiji, and became a central representation of East Asian Yogācāra.[14] Xuanzang also promoted devotional meditative practices toward Maitreya Bodhisattva.

Xuanzang's disciple Kuiji wrote a number of important commentaries on the Yogācāra texts and further developed the influence of this doctrine in China, and was recognized by later adherents as the first true patriarch of the school.[15]

After Xuanzang, the second patriarch of the Weishi school was Hui Zhao. According to A.C. Muller "Hui Zhao 惠沼 (650-714), the second patriarch, and Zhi Zhou 智周 (668-723), the third patriarch, wrote commentaries on the Fayuan yulin chang, the Lotus Sūtra, and the Madhyāntavibhāga; they also wrote treatises on Buddhist logic and commentaries on the Cheng weishi lun."[5] After the third patriarch, the school's influence declined and eventually it ceased to exist as an independent tradition, though its texts remained important sources for the study of Yogacara.[5]

Later history and the modern era

In time, Chinese Yogācāra was weakened due to competition with other Chinese Buddhist traditions such as Tiantai, Huayan, Chan and Pure Land Buddhism. Nevertheless, it continued to exert an influence, and Chinese Buddhists relied on its translations, commentaries, and concepts heavily, absorbing Yogācāra teachings into the other traditions.[13]

Yogācāra teachings and concepts remained popular in Chinese Buddhism, including visions of the bodhisattva Maitreya and teachings given from him in Tuṣita, usually observed by advanced meditators. One such example is that of Hanshan Deqing during the Ming dynasty. In his autobiography, Hanshan describes the palace of Maitreya in Tuṣita, and hearing a lecture given by Maitreya to a large group of his disciples.

In a moment I saw that tall, dignified monks were standing in line before the throne. Suddenly, a bhikṣu, holding a sutra in his hands, came down from behind the throne and handed the sutra to me, saying, "Master is going to talk about this sutra. He asked me to give it to you." I received it with joy but when I opened it I saw that it was written in gold Sanskrit letters which I could not read. I put it inside my robe and asked, "Who is the Master?" The bhiksu replied, "Maitreya."[16]

Hanshan recalls the teaching given as the following:

Maitreya said, "Discrimination is consciousness. Nondiscrimination is wisdom. Clinging to consciousness will bring disgrace but clinging to wisdom will bring purity. Disgrace leads to birth and death but purity leads to Nirvana." I listened to him as if I were in a dream within the dream. His voice, like the sound of tinkling crystal, floated on the air. I could hear him so clearly that even when I awoke his words kept on repeating in my mind. Now I realized the difference between consciousness and wisdom. Now I realized also that the place where I had been in my dream was Maitreya Buddha's Chamber in Tushita Heaven.[16]

In the early part of the 20th century, the laymen Yang Wenhui and Ouyang Jian (歐陽漸) (1871–1943) promoted Buddhist learning in China, and the general trend was for an increase in studies of Buddhist traditions such as Yogācāra, Sanlun, and Huayan.[17][18] In his 1929 book on the history of Chinese Buddhism, Jiang Weiqiao wrote:

In modern times, there are few śramaṇa who research [Faxiang]. Various laypeople, however, take this field of study to be rigorous, systematic and clear, and close to science. For this reason, there are now many people researching it. Preeminent among those writing on the topic are those at Nanjing's Inner Studies Academy, headed by Ouyang Jian.[19]

Ouyang Jian founded the Chinese Institute of Inner Studies (Chinese: 支那內學院), which provided education in Yogācāra teachings and the Mahāyāna prajñā class of sūtras, given to both monastics and laypeople.[20] Many modern Chinese Buddhist scholars are second-generation descendants of this school or have been influenced by it indirectly.[20]

History in Japan

.jpg.webp)

The Consciousness-Only teachings were transmitted to Japan as Hossō, and they made considerable impact. One of the founders of the Hossō sect in Japan was Kuiji.[21] Although a relatively small Hossō sect exists in Japan to this day, its influence has diminished as the center of Buddhist authority moved away from Nara, and with the rise of the Ekayāna schools of Buddhism.[13] During its height, scholars of the Hossō school frequently debated with other emerging schools. Both the founder of Shingon Buddhism, Kūkai, and the founder of Tendai, Saichō, exchanged letters of debate with Hossō scholar Tokuitsu, which became particularly heated in the case of Saichō.[22] Nevertheless, the Hossō maintained amicable relations with the Shingon esoteric sect, and adopted its practices while providing further scholarship on Yogacara philosophy.

Hōnen, founder of the Jōdo-shū Pure Land sect, likewise sought advice from Hossō scholars of his time as a novice monk, and later debated with them after establishing his sect.[23] Another Hossō scholar, Jōkei was among Hōnen's toughest critics, and frequently sought to refute his teachings, while simultaneously striving, as Hōnen did, to make Buddhism accessible to a wider audience by reviving devotion to the bodhisattva Maitreya and teaching followers the benefits of rebirth in the Tuṣita rather than the pure land of Amitābha.[24] Jōkei is also a leading figure in the efforts to revive monastic discipline at places like Tōshōdai-ji, Kōfuku-ji and counted other notable monks among his disciples, including Eison, who founded the Shingon Risshu sect.[25]

During the Meiji period, as tourism became more common, the Hossō sect was the owner of several famous temples, notably Hōryū-ji and Kiyomizu-dera. However, as the Hossō sect had ceased Buddhist study centuries prior, the head priests were not content with giving part of their tourism income to the sect's organization. Following the end of World War II, the owners of these popular temples broke away from the Hossō sect, in 1950 and 1965, respectively. The sect still maintains Kōfuku-ji and Yakushi-ji.

History in Korea

East Asian Yogācāra (Chinese: 法相宗; Korean pronunciation: Beopsang) were transmitted to Korea. The most well-known Korean figure of Beopsang was Woncheuk, who studied under the Chinese monk Xuanzang. Woncheuk is well known amongst scholars of Tibetan Buddhism for his commentary on the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra. While in China, Woncheuk took as a disciple a Korean-born monk named Dojeung (Chinese: 道證), who travelled to Silla in 692 and propounded and propagated Woncheuk's exegetical tradition there where it flourished.

In Korea, Beopsang teachings did not endure long as a distinct school, but its teachings were frequently included in later schools of thought.[13]

Notes

- Siderits, Mark, Buddhism as philosophy, 2017, p. 146.

- Sheng-yen 2007, p. 13.

- Tagawa 2014, p. 1–10.

- Paul 1984, p. 6.

- Muller, A.C. "Quick Overview of the Faxiang School 法相宗". www.acmuller.net. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- King Pong Chiu (2016). Thomé H. Fang, Tang Junyi and Huayan Thought: A Confucian Appropriation of Buddhist Ideas in Response to Scientism in Twentieth-Century China, p. 53. BRILL.

- Kantor, Hans-Rudolf. "Philosophical Aspects of Sixth-Century Chinese Buddhist Debates on “Mind and Consciousness”", pp. 337–395 in: Chen-kuo Lin / Michael Radich (eds.) A Distant Mirror Articulating Indic Ideas in Sixth and Seventh Century Chinese Buddhism. Hamburg Buddhist Studies, 3 Hamburg: Hamburg University Press 2014.

- Muller, Charles. 地論宗 School of the Treatise on the Bhūmis (2017), Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. http://www.buddhism-dict.net

- Paul 1984, p. 32-33.

- Keng Ching and Michael Radich. "Paramārtha." Brill's Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Volume II: Lives, edited by Jonathan A. Silk (editor-in chief), Richard Bowring, Vincent Eltschinger, and Michael Radich, 752-758. Leiden, Brill, 2019.

- Liu 2006, p. 220.

- Wei Tat. Cheng Weishi Lun. 1973. p. li

- Tagawa 2014, p. xx-xxi.

- Liu 2006, p. 221.

- Buswell & Lopez 2013, p. 283-4.

- Hanshan Deqing 1995.

- Nan 1997, p. 42.

- Sheng-yen 2007, p. 217.

- Hammerstrom, Erik J. (2010). "The Expression "The Myriad Dharmas are Only Consciousness" in Early 20th Century Chinese Buddhism" (PDF). Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal 中華佛學學報. 23: 73.

- Nan 1997, p. 141.

- Sho, Kyodai (2002). The Elementary-Level Textbook: Part 1: Gosho Study "Letter To The Brothers". SGI-USA Study Curriculum. Source: "Elementary Study - Letter to the Brothers". Archived from the original on 2007-12-15. Retrieved 2008-01-07. (accessed: January 8, 2007)

- Abe 1999, p. 208–19.

- "JODO SHU English". www.jodo.org.

- Ford 2006b, p. 110–113.

- Ford 2006a, p. 132–134.

Bibliography

- Abe, Ryūichi (1999). The Weaving of Mantra: Kūkai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-52887-0.

- Buswell, Robert; Lopez, Donald S. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3.

- Ford, James L. (2006a). Jōkei and Buddhist Devotion in Early Medieval Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972004-0.

- Ford, James (18 April 2006b). "Buddhist Ceremonials (Kōshiki) and the Ideological Discourse of Established Buddhism in Medieval Japan". In Payne, Richard K.; Leighton, Taigen Dan (eds.). Discourse and Ideology in Medieval Japanese Buddhism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-24209-2.

- Hamar, Imre (2007). Reflecting Mirrors: Perspectives on Huayan Buddhism. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-05509-3.

- Hanshan Deqing (1995). The Autobiography & Maxims of Master Han Shan. H.K. Buddhist Book.

- Liu, JeeLoo (2006). An Introduction to Chinese Philosophy: From Ancient Philosophy to Chinese Buddhism. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-2949-7.

- Minagawa, Sachiyoshi (1998). "Medieval Japanese Vijnaptimatra Thought-On nyakunmuro". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 46 (2).

- Nan, Huaijin (1997). Basic Buddhism: Exploring Buddhism and Zen. Weiser Books. ISBN 978-1-57863-020-2.

- Paul, Diana Y. (1984). Philosophy of Mind in Sixth-century China: Paramārtha's "evolution of Consciousness". Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-1187-6.

- Puggioni, Tonino (2003). "The Yogacara-faxiang faith and the Korean Beopsang [法相] tradition" (PDF). Seoul Journal of Korean Studies. 16: 75–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-14.

- Sheng-yen (2007). Orthodox Chinese Buddhism: A Contemporary Chan Master's Answers to Common Questions. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-657-4.

- Tagawa, Shun'ei (2014). Living Yogacara: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-895-5.

- Yoshimura, Hiromi (2006). "Plural Theories on Vijnaptimatra in the Mahayanasutralamkara". Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies. 54 (2).