Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj

Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj[lower-alpha 1] (Mongolian: Дашдоржийн Нацагдорж; 17 November 1906 – 13 July 1937), was a Mongolian writer, poet, playwright, and journalist. He is considered the founder and most-widely read author of modern Mongolian literature, and an exponent of "socialist realism". His most famous works are the opera Three Fateful Hills (1934), about the 1921 revolution, and the poem "My Homeland" (1933), about Mongolia's natural beauty, in addition to short stories. Natsagdorj also held several government positions in Mongolia in the 1920s.

Biography

Dashdorjiin Natsagdorj was born on 17 November 1906 in Darkhan Zasag banner (modern Bayandelger District, Töv Province) to father Dashidorji, a heavily-indebted taiji (petty noble), and mother Pagma, who died when he was seven years old. Natsagdorj was taught to read and write by his father, and from the age of nine was tutored by a colleague of his. From 1917, he was employed as a scribe in the Bogd Khanate government's Ministry of War.[1][2]

In 1921, Natsagdorj joined the Mongolian Revolutionary Youth League (MRYL). After the 1921 revolution, he was private secretary to Damdin Sükhbaatar, and from April 1922 an assistant to the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party's Central Committee (CC). From 1923 to 1925, he was successively secretary of the CC, the party's Military Commission, and acting government secretary during Balingiin Tserendorj's premiership. Natsagdorj was elected a member of the presidium of the CC in August 1923, and then a deputy member from August 1924 to March 1925. He participated in the party's Second Congress in 1923 and Third Congress in 1924, which adopted Mongolia's first constitution. Natsagdorj also served as deputy chairman of the MRYL, and in 1925 was elected chairman of the Young Pioneers, its children's organization. He participated in the MRYL's shii jüjig (Beijing opera–style) plays, and wrote the lyrics of the Pioneers' anthem, "Song of the Pioneers". Natsagdorj was also editor of the Mongolian People's Army newspaper Ardyn Tsereg. In 1923, he married Damdiny Pagmadulam, who founded the Mongolian Women's Committee in 1924; their daughter, Tserendulam, was born in 1923.[1][2]

In the autumn of 1925, at age 19, Natsagdorj left his government positions to study, first at Leningrad's Military-Political Academy. In September 1926, he and his wife joined a group of 35 Mongolian youths sent for educations in Germany and France. Natsagdorj attended the University of Berlin's journalism school and Leipzig University, where he studied with the Mongolist Erich Haenisch; Pagmadulam attended the Leipzig Higher School for Women. In 1929, after the Mongolian government recalled all students studying outside the Soviet Union, Natsagdorj worked as a researcher in the history department of the Institute of Scripture and Manuscripts (later the Mongolian Academy of Sciences). In 1930, he worked with Tsyben Zhamtsarano on a translation of the first volume of Karl Marx's Das Kapital, and later translated several books and stories to Mongolian from their German originals or translations, including Marco Polo's travels, a Mongolian history by the tsarist adviser Ivan Korostovets, and Edgar Allan Poe's short story "The Gold-Bug"; he also translated poems by Alexander Pushkin and some works by Anton Chekhov. Natsagdorj also served as head of the Ideology Department of the Central Committee, secretary of the Mongolian Revolutionary Writers' Organization (1930–1937), and the literary editor of the MRYL newspaper Zaluuchuudyn Ünen ("Youth Truth").[1][2]

Natsagdorj was arrested on 17 May 1932 for allegedly making a "slanderous statement" while celebrating the lunar new year (Tsagaan Sar). Pagmadulam (with whom Natsagdorj had separated) and others who had studied in Germany were also arrested. He was said to be involved with the "left deviationists", and described in police reports as a taiji. However, as he had neither "joined the Whites" nor "spoken or acted against the state", the special commission of the Internal Affairs Directorate sentenced him to a year's probation on 29 October 1932. Natsagdorj married Nina Ivanovna Chistyakova, a Soviet German woman whom he had met in Leningrad; their daughter, Ananda Shiri, was born on 22 March 1934. In 1935, Chistyakova and Ananda Shiri left Mongolia for Leningrad; some sources say that she had overstayed her visa, but others say Natsagdorj had taken to heavy drinking and secret liaisons with women.[1][2]

On 8 February 1937, Natsagdorj was arrested again on false charges during the early Stalinist purges in Mongolia, and was sentenced to five months of forced labor. He died of a stroke on a street in Ulaanbaatar on 13 July 1937, aged 30. A investigation into his arrest in 1989 declared him innocent.[1][2]

Works

Natsagdorj wrote poems, short stories, and dramas, and has been described as an exponent of "socialist realism" and Mongolia's "first classic of the socialist period". His best known work is Three Fateful Hills (Uchirtai gurvan tolgoi; 1934), an opera about the 1921 revolution which is still popular and performed today. Presented in verse strongly reminiscent of folk poetry, it has the common revolutionary theme of a young couple's love thwarted by tyrannical lords. Its tragic ending was rewritten after Natsagdorj's death to accord with revolutionary optimism.[1][2]

Only a few works by Natsagdorj before his time in Germany survive, though a now-lost play, Monggolun ügeigüü ail-un khöbegün ("Son of a Mongolian Proletarian Family"; 1924) won an award. While living in Germany, he wrote several poems, including "From Ulan Bator to Berlin" (1926) and "To a Distant Country for Education" (1927). The latter's widely-quoted final lines read: "From lands that geese cannot attain by wing / The child of man returns, in his bosom jewels enfolding". His first prose sketch, "May Day in a Capitalist Country", expressed admiration of the labor movement in Germany and his shame that revolutionary Mongolia had not mustered the same spirit.[1][2]

Natsagdorj's main period of productivity came from 1929 to his death. His iconic poem, "My Homeland" (Minii nutag; 1932 or 1933) describes the beauty of Mongolia's mountains and rivers. During his imprisonment in 1932, he scrawled poems of longing for his wife, for the beauties of nature, and for freedom. Other poems he wrote for programmatic purposes, such as promoting hygiene and modern medicine. Natsagdorj's "White Moon and Black Tears" (1932) is a story about the changes in Mongolian life after the revolution. His famous short story "Son of the Old World" or "Young Old-Timer" (Khuuchin khüü; 1930) paints a picture of the isolation and changelessness of the steppe, while "Tears of the Reverend Lama" (Lambuguain nulims) presents a portrait of a lama from the countryside arriving at Gandantegchinlen Monastery and falling in love with a fickle Chinese prostitute. His later poems and stories, written during the government's "new turn" period, show a more romantic attitude toward the life of rural herders. His last work, "History Poem", was written in 1936.[1][2]

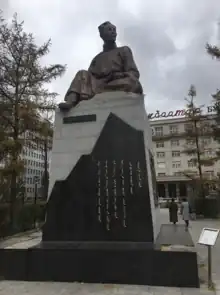

Monument

A monument to Natsagdorj stands in the gardens in front of the Ulaanbaatar Hotel, in a spot previously occupied by a statue of Vladimir Lenin. Before 2013, the statue of Natsagdorj stood next to the city's Wedding Palace.[1][2]

Notes

- Also spelled Dashdorjiyn, and Natsugdorji or Nachugdorji