Data Encryption Standard

The Data Encryption Standard (DES /ˌdiːˌiːˈɛs, dɛz/) is a symmetric-key algorithm for the encryption of digital data. Although its short key length of 56 bits makes it too insecure for modern applications, it has been highly influential in the advancement of cryptography.

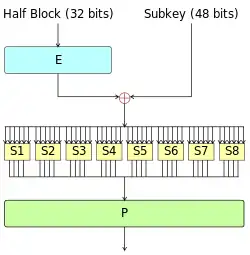

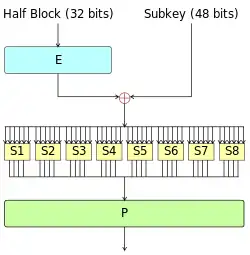

The Feistel function (F function) of DES | |

| General | |

|---|---|

| Designers | IBM |

| First published | 1975 (Federal Register) (standardized in January 1977) |

| Derived from | Lucifer |

| Successors | Triple DES, G-DES, DES-X, LOKI89, ICE |

| Cipher detail | |

| Key sizes | 56 bits |

| Block sizes | 64 bits |

| Structure | Balanced Feistel network |

| Rounds | 16 |

| Best public cryptanalysis | |

| DES has been considered unsecure right from the start because of the feasibility of brute-force attacks.[1] Such attacks have been demonstrated in practice (see EFF DES cracker) and are now available on the market as a service. As of 2008, the best analytical attack is linear cryptanalysis, which requires 243 known plaintexts and has a time complexity of 239–43 (Junod, 2001). | |

Developed in the early 1970s at IBM and based on an earlier design by Horst Feistel, the algorithm was submitted to the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) following the agency's invitation to propose a candidate for the protection of sensitive, unclassified electronic government data. In 1976, after consultation with the National Security Agency (NSA), the NBS selected a slightly modified version (strengthened against differential cryptanalysis, but weakened against brute-force attacks), which was published as an official Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) for the United States in 1977.[2]

The publication of an NSA-approved encryption standard led to its quick international adoption and widespread academic scrutiny. Controversies arose from classified design elements, a relatively short key length of the symmetric-key block cipher design, and the involvement of the NSA, raising suspicions about a backdoor. The S-boxes that had prompted those suspicions were designed by the NSA to remove a backdoor they secretly knew (differential cryptanalysis). However, the NSA also ensured that the key size was drastically reduced so that they could break the cipher by brute force attack.[2] The intense academic scrutiny the algorithm received over time led to the modern understanding of block ciphers and their cryptanalysis.

DES is insecure due to the relatively short 56-bit key size. In January 1999, distributed.net and the Electronic Frontier Foundation collaborated to publicly break a DES key in 22 hours and 15 minutes (see § Chronology). There are also some analytical results which demonstrate theoretical weaknesses in the cipher, although they are infeasible in practice. The algorithm is believed to be practically secure in the form of Triple DES, although there are theoretical attacks. This cipher has been superseded by the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). DES has been withdrawn as a standard by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.[3]

Some documents distinguish between the DES standard and its algorithm, referring to the algorithm as the DEA (Data Encryption Algorithm).

History

The origins of DES date to 1972, when a National Bureau of Standards study of US government computer security identified a need for a government-wide standard for encrypting unclassified, sensitive information.[4]

Around the same time, engineer Mohamed Atalla in 1972 founded Atalla Corporation and developed the first hardware security module (HSM), the so-called "Atalla Box" which was commercialized in 1973. It protected offline devices with a secure PIN generating key, and was a commercial success. Banks and credit card companies were fearful that Atalla would dominate the market, which spurred the development of an international encryption standard.[3] Atalla was an early competitor to IBM in the banking market, and was cited as an influence by IBM employees who worked on the DES standard.[5] The IBM 3624 later adopted a similar PIN verification system to the earlier Atalla system.[6]

On 15 May 1973, after consulting with the NSA, NBS solicited proposals for a cipher that would meet rigorous design criteria. None of the submissions was suitable. A second request was issued on 27 August 1974. This time, IBM submitted a candidate which was deemed acceptable—a cipher developed during the period 1973–1974 based on an earlier algorithm, Horst Feistel's Lucifer cipher. The team at IBM involved in cipher design and analysis included Feistel, Walter Tuchman, Don Coppersmith, Alan Konheim, Carl Meyer, Mike Matyas, Roy Adler, Edna Grossman, Bill Notz, Lynn Smith, and Bryant Tuckerman.

NSA's involvement in the design

On 17 March 1975, the proposed DES was published in the Federal Register. Public comments were requested, and in the following year two open workshops were held to discuss the proposed standard. There was criticism received from public-key cryptography pioneers Martin Hellman and Whitfield Diffie,[1] citing a shortened key length and the mysterious "S-boxes" as evidence of improper interference from the NSA. The suspicion was that the algorithm had been covertly weakened by the intelligence agency so that they—but no one else—could easily read encrypted messages.[7] Alan Konheim (one of the designers of DES) commented, "We sent the S-boxes off to Washington. They came back and were all different."[8] The United States Senate Select Committee on Intelligence reviewed the NSA's actions to determine whether there had been any improper involvement. In the unclassified summary of their findings, published in 1978, the Committee wrote:

In the development of DES, NSA convinced IBM that a reduced key size was sufficient; indirectly assisted in the development of the S-box structures; and certified that the final DES algorithm was, to the best of their knowledge, free from any statistical or mathematical weakness.[9]

However, it also found that

NSA did not tamper with the design of the algorithm in any way. IBM invented and designed the algorithm, made all pertinent decisions regarding it, and concurred that the agreed upon key size was more than adequate for all commercial applications for which the DES was intended.[10]

Another member of the DES team, Walter Tuchman, stated "We developed the DES algorithm entirely within IBM using IBMers. The NSA did not dictate a single wire!"[11] In contrast, a declassified NSA book on cryptologic history states:

In 1973 NBS solicited private industry for a data encryption standard (DES). The first offerings were disappointing, so NSA began working on its own algorithm. Then Howard Rosenblum, deputy director for research and engineering, discovered that Walter Tuchman of IBM was working on a modification to Lucifer for general use. NSA gave Tuchman a clearance and brought him in to work jointly with the Agency on his Lucifer modification."[12]

and

NSA worked closely with IBM to strengthen the algorithm against all except brute-force attacks and to strengthen substitution tables, called S-boxes. Conversely, NSA tried to convince IBM to reduce the length of the key from 64 to 48 bits. Ultimately they compromised on a 56-bit key.[13][14]

Some of the suspicions about hidden weaknesses in the S-boxes were allayed in 1990, with the independent discovery and open publication by Eli Biham and Adi Shamir of differential cryptanalysis, a general method for breaking block ciphers. The S-boxes of DES were much more resistant to the attack than if they had been chosen at random, strongly suggesting that IBM knew about the technique in the 1970s. This was indeed the case; in 1994, Don Coppersmith published some of the original design criteria for the S-boxes.[15] According to Steven Levy, IBM Watson researchers discovered differential cryptanalytic attacks in 1974 and were asked by the NSA to keep the technique secret.[16] Coppersmith explains IBM's secrecy decision by saying, "that was because [differential cryptanalysis] can be a very powerful tool, used against many schemes, and there was concern that such information in the public domain could adversely affect national security." Levy quotes Walter Tuchman: "[t]hey asked us to stamp all our documents confidential... We actually put a number on each one and locked them up in safes, because they were considered U.S. government classified. They said do it. So I did it".[16] Bruce Schneier observed that "It took the academic community two decades to figure out that the NSA 'tweaks' actually improved the security of DES."[17]

The algorithm as a standard

Despite the criticisms, DES was approved as a federal standard in November 1976, and published on 15 January 1977 as FIPS PUB 46, authorized for use on all unclassified data. It was subsequently reaffirmed as the standard in 1983, 1988 (revised as FIPS-46-1), 1993 (FIPS-46-2), and again in 1999 (FIPS-46-3), the latter prescribing "Triple DES" (see below). On 26 May 2002, DES was finally superseded by the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), following a public competition. On 19 May 2005, FIPS 46-3 was officially withdrawn, but NIST has approved Triple DES through the year 2030 for sensitive government information.[18]

The algorithm is also specified in ANSI X3.92 (Today X3 is known as INCITS and ANSI X3.92 as ANSI INCITS 92),[19] NIST SP 800-67[18] and ISO/IEC 18033-3[20] (as a component of TDEA).

Another theoretical attack, linear cryptanalysis, was published in 1994, but it was the Electronic Frontier Foundation's DES cracker in 1998 that demonstrated that DES could be attacked very practically, and highlighted the need for a replacement algorithm. These and other methods of cryptanalysis are discussed in more detail later in this article.

The introduction of DES is considered to have been a catalyst for the academic study of cryptography, particularly of methods to crack block ciphers. According to a NIST retrospective about DES,

- The DES can be said to have "jump-started" the nonmilitary study and development of encryption algorithms. In the 1970s there were very few cryptographers, except for those in military or intelligence organizations, and little academic study of cryptography. There are now many active academic cryptologists, mathematics departments with strong programs in cryptography, and commercial information security companies and consultants. A generation of cryptanalysts has cut its teeth analyzing (that is, trying to "crack") the DES algorithm. In the words of cryptographer Bruce Schneier,[21] "DES did more to galvanize the field of cryptanalysis than anything else. Now there was an algorithm to study." An astonishing share of the open literature in cryptography in the 1970s and 1980s dealt with the DES, and the DES is the standard against which every symmetric key algorithm since has been compared.[22]

Chronology

| Date | Year | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 15 May | 1973 | NBS publishes a first request for a standard encryption algorithm |

| 27 August | 1974 | NBS publishes a second request for encryption algorithms |

| 17 March | 1975 | DES is published in the Federal Register for comment |

| August | 1976 | First workshop on DES |

| September | 1976 | Second workshop, discussing mathematical foundation of DES |

| November | 1976 | DES is approved as a standard |

| 15 January | 1977 | DES is published as a FIPS standard FIPS PUB 46 |

| June | 1977 | Diffie and Hellman argue that the DES cipher can be broken by brute force.[1] |

| 1983 | DES is reaffirmed for the first time | |

| 1986 | Videocipher II, a TV satellite scrambling system based upon DES, begins use by HBO | |

| 22 January | 1988 | DES is reaffirmed for the second time as FIPS 46-1, superseding FIPS PUB 46 |

| July | 1991 | Biham and Shamir rediscover differential cryptanalysis, and apply it to a 15-round DES-like cryptosystem. |

| 1992 | Biham and Shamir report the first theoretical attack with less complexity than brute force: differential cryptanalysis. However, it requires an unrealistic 247 chosen plaintexts. | |

| 30 December | 1993 | DES is reaffirmed for the third time as FIPS 46-2 |

| 1994 | The first experimental cryptanalysis of DES is performed using linear cryptanalysis (Matsui, 1994). | |

| June | 1997 | The DESCHALL Project breaks a message encrypted with DES for the first time in public. |

| July | 1998 | The EFF's DES cracker (Deep Crack) breaks a DES key in 56 hours. |

| January | 1999 | Together, Deep Crack and distributed.net break a DES key in 22 hours and 15 minutes. |

| 25 October | 1999 | DES is reaffirmed for the fourth time as FIPS 46-3, which specifies the preferred use of Triple DES, with single DES permitted only in legacy systems. |

| 26 November | 2001 | The Advanced Encryption Standard is published in FIPS 197 |

| 26 May | 2002 | The AES becomes effective |

| 26 July | 2004 | The withdrawal of FIPS 46-3 (and a couple of related standards) is proposed in the Federal Register[23] |

| 19 May | 2005 | NIST withdraws FIPS 46-3 (see Federal Register vol 70, number 96) |

| April | 2006 | The FPGA-based parallel machine COPACOBANA of the Universities of Bochum and Kiel, Germany, breaks DES in 9 days at a $10,000 hardware cost.[24] Within a year software improvements reduced the average time to 6.4 days. |

| Nov. | 2008 | The successor of COPACOBANA, the RIVYERA machine, reduced the average time to less than a single day. |

| August | 2016 | The Open Source password cracking software hashcat added in DES brute force searching on general purpose GPUs. Benchmarking shows a single off the shelf Nvidia GeForce GTX 1080 Ti GPU costing US$1000 recovers a key in an average of 15 days (full exhaustive search taking 30 days). Systems have been built with eight GTX 1080 Ti GPUs which can recover a key in an average of under 2 days.[25] |

| July | 2017 | A chosen-plaintext attack utilizing a rainbow table can recover the DES key for a single specific chosen plaintext 1122334455667788 in 25 seconds. A new rainbow table has to be calculated per plaintext. A limited set of rainbow tables have been made available for download.[26] |

Description

DES is the archetypal block cipher—an algorithm that takes a fixed-length string of plaintext bits and transforms it through a series of complicated operations into another ciphertext bitstring of the same length. In the case of DES, the block size is 64 bits. DES also uses a key to customize the transformation, so that decryption can supposedly only be performed by those who know the particular key used to encrypt. The key ostensibly consists of 64 bits; however, only 56 of these are actually used by the algorithm. Eight bits are used solely for checking parity, and are thereafter discarded. Hence the effective key length is 56 bits.

The key is nominally stored or transmitted as 8 bytes, each with odd parity. According to ANSI X3.92-1981 (Now, known as ANSI INCITS 92–1981), section 3.5:

One bit in each 8-bit byte of the KEY may be utilized for error detection in key generation, distribution, and storage. Bits 8, 16,..., 64 are for use in ensuring that each byte is of odd parity.

Like other block ciphers, DES by itself is not a secure means of encryption, but must instead be used in a mode of operation. FIPS-81 specifies several modes for use with DES.[27] Further comments on the usage of DES are contained in FIPS-74.[28]

Decryption uses the same structure as encryption, but with the keys used in reverse order. (This has the advantage that the same hardware or software can be used in both directions.)

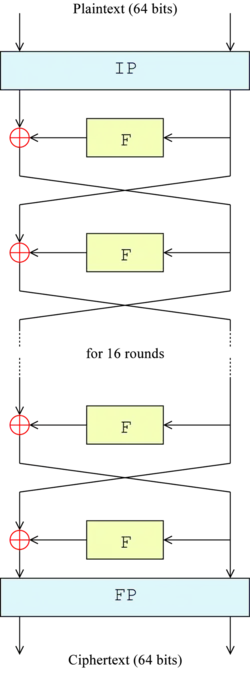

Overall structure

The algorithm's overall structure is shown in Figure 1: there are 16 identical stages of processing, termed rounds. There is also an initial and final permutation, termed IP and FP, which are inverses (IP "undoes" the action of FP, and vice versa). IP and FP have no cryptographic significance, but were included in order to facilitate loading blocks in and out of mid-1970s 8-bit based hardware.[29]

Before the main rounds, the block is divided into two 32-bit halves and processed alternately; this criss-crossing is known as the Feistel scheme. The Feistel structure ensures that decryption and encryption are very similar processes—the only difference is that the subkeys are applied in the reverse order when decrypting. The rest of the algorithm is identical. This greatly simplifies implementation, particularly in hardware, as there is no need for separate encryption and decryption algorithms.

The ⊕ symbol denotes the exclusive-OR (XOR) operation. The F-function scrambles half a block together with some of the key. The output from the F-function is then combined with the other half of the block, and the halves are swapped before the next round. After the final round, the halves are swapped; this is a feature of the Feistel structure which makes encryption and decryption similar processes.

The Feistel (F) function

The F-function, depicted in Figure 2, operates on half a block (32 bits) at a time and consists of four stages:

- Expansion: the 32-bit half-block is expanded to 48 bits using the expansion permutation, denoted E in the diagram, by duplicating half of the bits. The output consists of eight 6-bit (8 × 6 = 48 bits) pieces, each containing a copy of 4 corresponding input bits, plus a copy of the immediately adjacent bit from each of the input pieces to either side.

- Key mixing: the result is combined with a subkey using an XOR operation. Sixteen 48-bit subkeys—one for each round—are derived from the main key using the key schedule (described below).

- Substitution: after mixing in the subkey, the block is divided into eight 6-bit pieces before processing by the S-boxes, or substitution boxes. Each of the eight S-boxes replaces its six input bits with four output bits according to a non-linear transformation, provided in the form of a lookup table. The S-boxes provide the core of the security of DES—without them, the cipher would be linear, and trivially breakable.

- Permutation: finally, the 32 outputs from the S-boxes are rearranged according to a fixed permutation, the P-box. This is designed so that, after permutation, the bits from the output of each S-box in this round are spread across four different S-boxes in the next round.

The alternation of substitution from the S-boxes, and permutation of bits from the P-box and E-expansion provides so-called "confusion and diffusion" respectively, a concept identified by Claude Shannon in the 1940s as a necessary condition for a secure yet practical cipher.

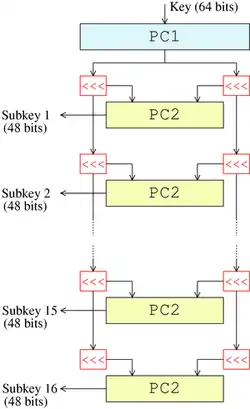

Key schedule

Figure 3 illustrates the key schedule for encryption—the algorithm which generates the subkeys. Initially, 56 bits of the key are selected from the initial 64 by Permuted Choice 1 (PC-1)—the remaining eight bits are either discarded or used as parity check bits. The 56 bits are then divided into two 28-bit halves; each half is thereafter treated separately. In successive rounds, both halves are rotated left by one or two bits (specified for each round), and then 48 subkey bits are selected by Permuted Choice 2 (PC-2)—24 bits from the left half, and 24 from the right. The rotations (denoted by "<<<" in the diagram) mean that a different set of bits is used in each subkey; each bit is used in approximately 14 out of the 16 subkeys.

The key schedule for decryption is similar—the subkeys are in reverse order compared to encryption. Apart from that change, the process is the same as for encryption. The same 28 bits are passed to all rotation boxes.

Pseudocode

Pseudocode for the DES algorithm follows.

// All variables are unsigned 64 bits

// Pre-processing: padding with the size difference in bytes

pad message to reach multiple of 64 bits in length

var key // The keys given by the user

var keys[16]

var left, right

// Generate Keys

// PC1 (64 bits to 56 bits)

key := permutation(key, PC1)

left := (key rightshift 28) and 0xFFFFFFF

right := key and 0xFFFFFFF

for i from 0 to 16 do

right := right leftrotate KEY_shift[i]

left := left leftrotate KEY_shift[i]

var concat := (left leftshift 28) or right

// PC2 (56bits to 48bits)

keys[i] := permutation(concat, PC2)

end for

// To decrypt a message reverse the order of the keys

if decrypt do

reverse keys

end if

// Encrypt or Decrypt

for each 64-bit chunk of padded message do

var tmp

// IP

chunk := permutation(chunk, IP)

left := chunk rightshift 32

right := chunk and 0xFFFFFFFF

for i from 0 to 16 do

tmp := right

// E (32bits to 48bits)

right := expansion(right, E)

right := right xor keys[i]

// Substitution (48bits to 32bits)

right := substitution(right)

// P

right := permutation(right, P)

right := right xor left

left := tmp

end for

// Concat right and left

var cipher_chunk := (right leftshift 32) or left

// FP

cipher_chunk := permutation(cipher_chunk, FP)

end for

Security and cryptanalysis

Although more information has been published on the cryptanalysis of DES than any other block cipher, the most practical attack to date is still a brute-force approach. Various minor cryptanalytic properties are known, and three theoretical attacks are possible which, while having a theoretical complexity less than a brute-force attack, require an unrealistic number of known or chosen plaintexts to carry out, and are not a concern in practice.

Brute-force attack

For any cipher, the most basic method of attack is brute force—trying every possible key in turn. The length of the key determines the number of possible keys, and hence the feasibility of this approach. For DES, questions were raised about the adequacy of its key size early on, even before it was adopted as a standard, and it was the small key size, rather than theoretical cryptanalysis, which dictated a need for a replacement algorithm. As a result of discussions involving external consultants including the NSA, the key size was reduced from 256 bits to 56 bits to fit on a single chip.[30]

In academia, various proposals for a DES-cracking machine were advanced. In 1977, Diffie and Hellman proposed a machine costing an estimated US$20 million which could find a DES key in a single day.[1][31] By 1993, Wiener had proposed a key-search machine costing US$1 million which would find a key within 7 hours. However, none of these early proposals were ever implemented—or, at least, no implementations were publicly acknowledged. The vulnerability of DES was practically demonstrated in the late 1990s.[32] In 1997, RSA Security sponsored a series of contests, offering a $10,000 prize to the first team that broke a message encrypted with DES for the contest. That contest was won by the DESCHALL Project, led by Rocke Verser, Matt Curtin, and Justin Dolske, using idle cycles of thousands of computers across the Internet. The feasibility of cracking DES quickly was demonstrated in 1998 when a custom DES-cracker was built by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), a cyberspace civil rights group, at the cost of approximately US$250,000 (see EFF DES cracker). Their motivation was to show that DES was breakable in practice as well as in theory: "There are many people who will not believe a truth until they can see it with their own eyes. Showing them a physical machine that can crack DES in a few days is the only way to convince some people that they really cannot trust their security to DES." The machine brute-forced a key in a little more than 2 days' worth of searching.

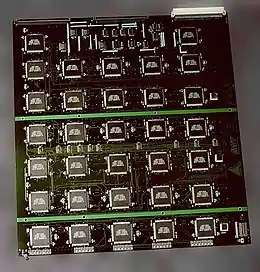

The next confirmed DES cracker was the COPACOBANA machine built in 2006 by teams of the Universities of Bochum and Kiel, both in Germany. Unlike the EFF machine, COPACOBANA consists of commercially available, reconfigurable integrated circuits. 120 of these field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) of type XILINX Spartan-3 1000 run in parallel. They are grouped in 20 DIMM modules, each containing 6 FPGAs. The use of reconfigurable hardware makes the machine applicable to other code breaking tasks as well.[33] One of the more interesting aspects of COPACOBANA is its cost factor. One machine can be built for approximately $10,000.[34] The cost decrease by roughly a factor of 25 over the EFF machine is an example of the continuous improvement of digital hardware—see Moore's law. Adjusting for inflation over 8 years yields an even higher improvement of about 30x. Since 2007, SciEngines GmbH, a spin-off company of the two project partners of COPACOBANA has enhanced and developed successors of COPACOBANA. In 2008 their COPACOBANA RIVYERA reduced the time to break DES to less than one day, using 128 Spartan-3 5000's. SciEngines RIVYERA held the record in brute-force breaking DES, having utilized 128 Spartan-3 5000 FPGAs.[35] Their 256 Spartan-6 LX150 model has further lowered this time.

In 2012, David Hulton and Moxie Marlinspike announced a system with 48 Xilinx Virtex-6 LX240T FPGAs, each FPGA containing 40 fully pipelined DES cores running at 400 MHz, for a total capacity of 768 gigakeys/sec. The system can exhaustively search the entire 56-bit DES key space in about 26 hours and this service is offered for a fee online.[36][37]

Attacks faster than brute force

There are three attacks known that can break the full 16 rounds of DES with less complexity than a brute-force search: differential cryptanalysis (DC),[38] linear cryptanalysis (LC),[39] and Davies' attack.[40] However, the attacks are theoretical and are generally considered infeasible to mount in practice;[41] these types of attack are sometimes termed certificational weaknesses.

- Differential cryptanalysis was rediscovered in the late 1980s by Eli Biham and Adi Shamir; it was known earlier to both IBM and the NSA and kept secret. To break the full 16 rounds, differential cryptanalysis requires 247 chosen plaintexts.[38] DES was designed to be resistant to DC.

- Linear cryptanalysis was discovered by Mitsuru Matsui, and needs 243 known plaintexts (Matsui, 1993);[39] the method was implemented (Matsui, 1994), and was the first experimental cryptanalysis of DES to be reported. There is no evidence that DES was tailored to be resistant to this type of attack. A generalization of LC—multiple linear cryptanalysis—was suggested in 1994 (Kaliski and Robshaw), and was further refined by Biryukov and others. (2004); their analysis suggests that multiple linear approximations could be used to reduce the data requirements of the attack by at least a factor of 4 (that is, 241 instead of 243).[42] A similar reduction in data complexity can be obtained in a chosen-plaintext variant of linear cryptanalysis (Knudsen and Mathiassen, 2000).[43] Junod (2001) performed several experiments to determine the actual time complexity of linear cryptanalysis, and reported that it was somewhat faster than predicted, requiring time equivalent to 239–241 DES evaluations.[44]

- Improved Davies' attack: while linear and differential cryptanalysis are general techniques and can be applied to a number of schemes, Davies' attack is a specialized technique for DES, first suggested by Donald Davies in the eighties,[40] and improved by Biham and Biryukov (1997).[45] The most powerful form of the attack requires 250 known plaintexts, has a computational complexity of 250, and has a 51% success rate.

There have also been attacks proposed against reduced-round versions of the cipher, that is, versions of DES with fewer than 16 rounds. Such analysis gives an insight into how many rounds are needed for safety, and how much of a "security margin" the full version retains.

Differential-linear cryptanalysis was proposed by Langford and Hellman in 1994, and combines differential and linear cryptanalysis into a single attack.[46] An enhanced version of the attack can break 9-round DES with 215.8 chosen plaintexts and has a 229.2 time complexity (Biham and others, 2002).[47]

Minor cryptanalytic properties

DES exhibits the complementation property, namely that

where is the bitwise complement of denotes encryption with key and denote plaintext and ciphertext blocks respectively. The complementation property means that the work for a brute-force attack could be reduced by a factor of 2 (or a single bit) under a chosen-plaintext assumption. By definition, this property also applies to TDES cipher.[48]

DES also has four so-called weak keys. Encryption (E) and decryption (D) under a weak key have the same effect (see involution):

- or equivalently,

There are also six pairs of semi-weak keys. Encryption with one of the pair of semiweak keys, , operates identically to decryption with the other, :

- or equivalently,

It is easy enough to avoid the weak and semiweak keys in an implementation, either by testing for them explicitly, or simply by choosing keys randomly; the odds of picking a weak or semiweak key by chance are negligible. The keys are not really any weaker than any other keys anyway, as they do not give an attack any advantage.

DES has also been proved not to be a group, or more precisely, the set (for all possible keys ) under functional composition is not a group, nor "close" to being a group.[49] This was an open question for some time, and if it had been the case, it would have been possible to break DES, and multiple encryption modes such as Triple DES would not increase the security, because repeated encryption (and decryptions) under different keys would be equivalent to encryption under another, single key.[50]

Simplified DES

Simplified DES (SDES) was designed for educational purposes only, to help students learn about modern cryptanalytic techniques. SDES has similar structure and properties to DES, but has been simplified to make it much easier to perform encryption and decryption by hand with pencil and paper. Some people feel that learning SDES gives insight into DES and other block ciphers, and insight into various cryptanalytic attacks against them.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

Replacement algorithms

Concerns about security and the relatively slow operation of DES in software motivated researchers to propose a variety of alternative block cipher designs, which started to appear in the late 1980s and early 1990s: examples include RC5, Blowfish, IDEA, NewDES, SAFER, CAST5 and FEAL. Most of these designs kept the 64-bit block size of DES, and could act as a "drop-in" replacement, although they typically used a 64-bit or 128-bit key. In the Soviet Union the GOST 28147-89 algorithm was introduced, with a 64-bit block size and a 256-bit key, which was also used in Russia later.

DES itself can be adapted and reused in a more secure scheme. Many former DES users now use Triple DES (TDES) which was described and analysed by one of DES's patentees (see FIPS Pub 46–3); it involves applying DES three times with two (2TDES) or three (3TDES) different keys. TDES is regarded as adequately secure, although it is quite slow. A less computationally expensive alternative is DES-X, which increases the key size by XORing extra key material before and after DES. GDES was a DES variant proposed as a way to speed up encryption, but it was shown to be susceptible to differential cryptanalysis.

On January 2, 1997, NIST announced that they wished to choose a successor to DES.[60] In 2001, after an international competition, NIST selected a new cipher, the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), as a replacement.[61] The algorithm which was selected as the AES was submitted by its designers under the name Rijndael. Other finalists in the NIST AES competition included RC6, Serpent, MARS, and Twofish.

See also

Notes

- Diffie, Whitfield; Hellman, Martin E. (June 1977). "Exhaustive Cryptanalysis of the NBS Data Encryption Standard" (PDF). Computer. 10 (6): 74–84. doi:10.1109/C-M.1977.217750. S2CID 2412454. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-26.

- "The Legacy of DES - Schneier on Security". www.schneier.com. October 6, 2004.

- Bátiz-Lazo, Bernardo (2018). Cash and Dash: How ATMs and Computers Changed Banking. Oxford University Press. pp. 284 & 311. ISBN 9780191085574.

- Walter Tuchman (1997). "A brief history of the data encryption standard". Internet besieged: countering cyberspace scofflaws. ACM Press/Addison-Wesley Publishing Co. New York, NY, USA. pp. 275–280.

- "The Economic Impacts of NIST's Data Encryption Standard (DES) Program" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. United States Department of Commerce. October 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Konheim, Alan G. (1 April 2016). "Automated teller machines: their history and authentication protocols". Journal of Cryptographic Engineering. 6 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s13389-015-0104-3. ISSN 2190-8516. S2CID 1706990. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- RSA Laboratories. "Has DES been broken?". Archived from the original on 2016-05-17. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- Schneier. Applied Cryptography (2nd ed.). p. 280.

- Davies, D.W.; W.L. Price (1989). Security for computer networks, 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons.

- Robert Sugarman, ed. (July 1979). "On foiling computer crime". IEEE Spectrum.

- P. Kinnucan (October 1978). "Data Encryption Gurus: Tuchman and Meyer". Cryptologia. 2 (4): 371. doi:10.1080/0161-117891853270.

- Thomas R. Johnson (2009-12-18). "American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989.Book III: Retrenchment and Reform, 1972-1980, page 232" (PDF). National Security Agency, DOCID 3417193 (file released on 2009-12-18, hosted at nsa.gov). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-18. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- Thomas R. Johnson (2009-12-18). "American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989.Book III: Retrenchment and Reform, 1972-1980, page 232" (PDF). National Security Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-25. Retrieved 2015-07-16 – via National Security Archive FOIA request. This version is differently redacted than the version on the NSA website.

- Thomas R. Johnson (2009-12-18). "American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989.Book III: Retrenchment and Reform, 1972-1980, page 232" (PDF). National Security Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-25. Retrieved 2015-07-16 – via National Security Archive FOIA request. This version is differently redacted than the version on the NSA website.

- Konheim. Computer Security and Cryptography. p. 301.

- Levy, Crypto, p. 55

- Schneier, Bruce (2004-09-27). "Saluting the data encryption legacy". CNet. Retrieved 2015-07-22.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST Special Publication 800-67 Recommendation for the Triple Data Encryption Algorithm (TDEA) Block Cipher, Version 1.1

- American National Standards Institute, ANSI X3.92-1981 (now known as ANSI INCITS 92-1981)American National Standard, Data Encryption Algorithm

- "ISO/IEC 18033-3:2010 Information technology—Security techniques—Encryption algorithms—Part 3: Block ciphers". Iso.org. 2010-12-14. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography, Protocols, Algorithms, and Source Code in C, Second edition, John Wiley and Sons, New York (1996) p. 267

- William E. Burr, "Data Encryption Standard", in NIST's anthology "A Century of Excellence in Measurements, Standards, and Technology: A Chronicle of Selected NBS/NIST Publications, 1901–2000. HTML Archived 2009-06-19 at the Wayback Machine PDF Archived 2006-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "FR Doc 04-16894". Edocket.access.gpo.gov. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- S. Kumar, C. Paar, J. Pelzl, G. Pfeiffer, A. Rupp, M. Schimmler, "How to Break DES for Euro 8,980". 2nd Workshop on Special-purpose Hardware for Attacking Cryptographic Systems—SHARCS 2006, Cologne, Germany, April 3–4, 2006.

- "8x1080Ti.md".

- "Crack.sh | the World's Fastest DES Cracker".

- "FIPS 81 - Des Modes of Operation". csrc.nist.gov. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- "FIPS 74 - Guidelines for Implementing and Using the NBS Data". Itl.nist.gov. Archived from the original on 2014-01-03. Retrieved 2009-06-02.

- Schneier. Applied Cryptography (1st ed.). p. 271.

- Stallings, W. Cryptography and network security: principles and practice. Prentice Hall, 2006. p. 73

- "Bruting DES".

- van Oorschot, Paul C.; Wiener, Michael J. (1991), Damgård, Ivan Bjerre (ed.), "A Known-Plaintext Attack on Two-Key Triple Encryption", Advances in Cryptology – EUROCRYPT ’90, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, vol. 473, pp. 318–325, doi:10.1007/3-540-46877-3_29, ISBN 978-3-540-53587-4

- "Getting Started, COPACOBANA — Cost-optimized Parallel Code-Breaker" (PDF). December 12, 2006. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- Reinhard Wobst (October 16, 2007). Cryptology Unlocked. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470060643.

- Break DES in less than a single day Archived 2017-08-28 at the Wayback Machine [Press release of Firm, demonstrated on 2009 Workshop]

- "The World's fastest DES cracker".

- Think Complex Passwords Will Save You?, David Hulton, Ian Foster, BSidesLV 2017

- Biham, E. & Shamir, A (1993). Differential cryptanalysis of the data encryption standard. Shamir, Adi. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 487–496. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-9314-6. ISBN 978-0387979304. OCLC 27173465. S2CID 6361693.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Matsui, Mitsuru (1993-05-23). "Linear Cryptanalysis Method for DES Cipher". Advances in Cryptology — EUROCRYPT '93. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 765. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 386–397. doi:10.1007/3-540-48285-7_33. ISBN 978-3540482857.

- Davies, D. W. (1987). "Investigation of a potential weakness in the DES algorithm, Private communications". Private Communications.

- Alanazi, Hamdan O.; et al. (2010). "New Comparative Study Between DES, 3DES and AES within Nine Factors". Journal of Computing. 2 (3). arXiv:1003.4085. Bibcode:2010arXiv1003.4085A.

- Biryukov, Alex; Cannière, Christophe De; Quisquater, Michaël (2004-08-15). "On Multiple Linear Approximations". Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2004. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3152. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-28628-8_1. ISBN 9783540226680.

- Knudsen, Lars R.; Mathiassen, John Erik (2000-04-10). "A Chosen-Plaintext Linear Attack on DES". Fast Software Encryption. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 1978. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 262–272. doi:10.1007/3-540-44706-7_18. ISBN 978-3540447061.

- Junod, Pascal (2001-08-16). "On the Complexity of Matsui's Attack". Selected Areas in Cryptography. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2259. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 199–211. doi:10.1007/3-540-45537-X_16. ISBN 978-3540455370.

- Biham, Eli; Biryukov, Alex (1997-06-01). "An improvement of Davies' attack on DES". Journal of Cryptology. 10 (3): 195–205. doi:10.1007/s001459900027. ISSN 0933-2790. S2CID 4070446.

- Langford, Susan K.; Hellman, Martin E. (1994-08-21). "Differential-Linear Cryptanalysis". Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO '94. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 839. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 17–25. doi:10.1007/3-540-48658-5_3. ISBN 978-3540486589.

- Biham, Eli; Dunkelman, Orr; Keller, Nathan (2002-12-01). "Enhancing Differential-Linear Cryptanalysis". Advances in Cryptology — ASIACRYPT 2002. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2501. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 254–266. doi:10.1007/3-540-36178-2_16. ISBN 978-3540361787.

- Menezes, Alfred J.; van Oorschot, Paul C.; Vanstone, Scott A. (1996). Handbook of Applied Cryptography. CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0849385230.

- Campbell and Wiener, 1992. 16 August 1992. pp. 512–520. ISBN 9783540573401.

- "Double DES" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-04-09.

- Sanjay Kumar; Sandeep Srivastava. "Image Encryption using Simplified Data Encryption Standard (S-DES)" Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine. 2014.

- Alasdair McAndrew. "Introduction to Cryptography with Open-Source Software". 2012. Section "8.8 Simplified DES: sDES". p. 183 to 190.

- William Stallings. "Appendix G: Simplified DES". 2010.

- Nalini N; G Raghavendra Rao. "Cryptanalysis of Simplified Data Encryption Standard via Optimisation Heuristics". 2006.

- Minh Van Nguyen. "Simplified DES". 2009.

- Dr. Manoj Kumar. "Cryptography and Network Security". Section 3.4: The Simplified Version of DES (S-DES). p. 96.

- Edward F. Schaefer. "A Simplified Data Encryption Standard Algorithm". doi:10.1080/0161-119691884799 1996.

- Lavkush Sharma; Bhupendra Kumar Pathak; and Nidhi Sharma. "Breaking of Simplified Data Encryption Standard Using Binary Particle Swarm Optimization". 2012.

- "Cryptography Research: Devising a Better Way to Teach and Learn the Advanced Encryption Standard".

- "Announcing Development of FIPS for Advanced Encryption Standard | CSRC". 10 January 2017.

- http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/fips/fips197/fips-197.pdf November 26, 2001.

References

- Biham, Eli and Shamir, Adi (1991). "Differential Cryptanalysis of DES-like Cryptosystems". Journal of Cryptology. 4 (1): 3–72. doi:10.1007/BF00630563. S2CID 206783462.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (preprint) - Biham, Eli and Shamir, Adi, Differential Cryptanalysis of the Data Encryption Standard, Springer Verlag, 1993. ISBN 0-387-97930-1, ISBN 3-540-97930-1.

- Biham, Eli and Alex Biryukov: An Improvement of Davies' Attack on DES. J. Cryptology 10(3): 195–206 (1997)

- Biham, Eli, Orr Dunkelman, Nathan Keller: Enhancing Differential-Linear Cryptanalysis. ASIACRYPT 2002: pp254–266

- Biham, Eli: A Fast New DES Implementation in Software

- Cracking DES: Secrets of Encryption Research, Wiretap Politics, and Chip Design, Electronic Frontier Foundation

- Biryukov, A, C. De Canniere and M. Quisquater (2004). Franklin, Matt (ed.). On Multiple Linear Approximations. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 3152. pp. 1–22. doi:10.1007/b99099. ISBN 978-3-540-22668-0. S2CID 27790868.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (preprint). - Campbell, Keith W., Michael J. Wiener: DES is not a Group. CRYPTO 1992: pp512–520

- Coppersmith, Don. (1994). The data encryption standard (DES) and its strength against attacks at the Wayback Machine (archived June 15, 2007). IBM Journal of Research and Development, 38(3), 243–250.

- Diffie, Whitfield and Martin Hellman, "Exhaustive Cryptanalysis of the NBS Data Encryption Standard" IEEE Computer 10(6), June 1977, pp74–84

- Ehrsam and others., Product Block Cipher System for Data Security, U.S. Patent 3,962,539, Filed February 24, 1975

- Gilmore, John, "Cracking DES: Secrets of Encryption Research, Wiretap Politics and Chip Design", 1998, O'Reilly, ISBN 1-56592-520-3.

- Junod, Pascal. "On the Complexity of Matsui's Attack." Selected Areas in Cryptography, 2001, pp199–211.

- Kaliski, Burton S., Matt Robshaw: Linear Cryptanalysis Using Multiple Approximations. CRYPTO 1994: pp26–39

- Knudsen, Lars, John Erik Mathiassen: A Chosen-Plaintext Linear Attack on DES. Fast Software Encryption - FSE 2000: pp262–272

- Langford, Susan K., Martin E. Hellman: Differential-Linear Cryptanalysis. CRYPTO 1994: 17–25

- Levy, Steven, Crypto: How the Code Rebels Beat the Government—Saving Privacy in the Digital Age, 2001, ISBN 0-14-024432-8.

- Matsui, Mitsuru (1994). Helleseth, Tor (ed.). Linear Cryptanalysis Method for DES Cipher. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 765. pp. 386–397. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.50.8472. doi:10.1007/3-540-48285-7. ISBN 978-3-540-57600-6. S2CID 21157010.

- Matsui, Mitsuru (1994). "The First Experimental Cryptanalysis of the Data Encryption Standard". Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO '94. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 839. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/3-540-48658-5_1. ISBN 978-3-540-58333-2.

- National Bureau of Standards, Data Encryption Standard, FIPS-Pub.46. National Bureau of Standards, U.S. Department of Commerce, Washington D.C., January 1977.

- Christof Paar, Jan Pelzl, "The Data Encryption Standard (DES) and Alternatives", free online lectures on Chapter 3 of "Understanding Cryptography, A Textbook for Students and Practitioners". Springer, 2009.

External links

- FIPS 46-3: The official document describing the DES standard (PDF)

- COPACOBANA, a $10,000 DES cracker based on FPGAs by the Universities of Bochum and Kiel

- DES step-by-step presentation and reliable message encoding application

- A Fast New DES Implementation in Software - Biham

- On Multiple Linear Approximations

- RFC4772 : Security Implications of Using the Data Encryption Standard (DES)

- Python code of DES Cipher implemented using DES Chapter from NIST SP 958