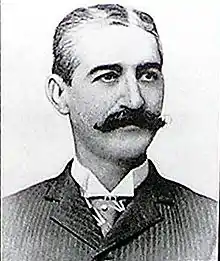

David Hennessy

David C. Hennessy (1858 – October 16, 1890) was a police chief of New Orleans. As a young detective, he made headlines in 1881 when he captured a notorious Italian criminal, Giuseppe Esposito. In 1888, he was promoted to superintendent and chief of police. While in office he made a number of improvements to the force, and was well known and respected in the New Orleans community.

David Hennessy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1858 New Orleans, Louisiana, US |

| Died | October 16, 1890 (aged 31–32) New Orleans, Louisiana, US |

| Police career | |

| Department | New Orleans Police Department |

| Rank | Police chief |

His assassination in 1890 led to a sensational trial. A series of acquittals and mistrials in March 1891 angered locals, and an enormous mob forced open the prison doors and lynched 11 of the 19 Italian men who had been indicted for Hennessy's murder in the largest known mass lynching in U.S. history.

Early life

David C. Hennessy was born in New Orleans to Margaret and David Hennessy Sr., Irish Catholics living on Girod Street. David Sr. was a member of the First Louisiana Cavalry of the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War, formed after the state was occupied by Union troops. After the war, during the Reconstruction era, he served with the Metropolitan Police, a New Orleans force under the authority of the governor of Louisiana. Local white Democrats generally considered the Metropolitan Police as a military occupation army, in part because it protected the right of freedmen to vote, in accordance with the Fifteenth Amendment. David Sr. was murdered in 1869 by Arthur Guerin, a fellow policeman.[1]

Career

Hennessy joined the New Orleans police force as a messenger in 1870. While only a teenager, he caught two adult thieves in the act, beat them with his bare hands, and dragged them to the police station. He made detective at the age of 20.

With his cousin Michael Hennessy and private detectives James Mooney and John Boland of New York City, he arrested the notorious Italian bandit and fugitive Giuseppe Esposito in 1881. Esposito was wanted in Italy for kidnapping a British tourist and cutting off his ear, among numerous other crimes. Esposito was deported to Italy, where he was given a life sentence.[2]

In 1882, Hennessy was tried for the murder of New Orleans Chief of Detectives Thomas Devereaux. At the time, both men were candidates for the position of chief. Hennessy argued self-defense and was found not guilty.[3] Hennessy left the department afterwards and joined a private security firm given police powers by the city. He handled security for the New Orleans World Fair of 1884–1885.[4] The New York Times noted that Hennessy's men were, "neatly uniformed and are a fine-looking and intelligent body of men, far superior to the regular city force."[5]

In 1888, Joseph A. Shakspeare, the nominee of the Young Men's Democratic Association, was elected mayor of New Orleans with Republican support. Having promised to end police inefficiency, Shakspeare promptly appointed Hennessy as his police chief.[2]

Hennessy inherited a police force that was (according to the local press) incompetent and plagued by corruption. Under his supervision, it began to show signs of improvement.[6]

Assassination

On the evening of October 15, 1890, Hennessy was shot by several gunmen as he walked home from work. It is likely that the gunmen were wielding sawn-off shotguns—known in Italian terms as lupara—a common type of execution among Mafiosi. Hennessy returned fire and chased his attackers before collapsing. When asked who had shot him, Hennessy reportedly whispered to Captain William O'Connor: "Dagos." Hennessy was awake in the hospital for several hours after the shooting and spoke to friends but did not name the shooters. The next day he died from complications related to his injuries.[7][8] Hennessy was buried in Metairie Cemetery.[9]

There had been an ongoing feud between the Provenzano and Mantranga families, who were business rivals on the New Orleans waterfront. Hennessy had put several of the Provenzanos in prison, and their appeal trial was coming up. According to some reports, Hennessy had been planning to offer new evidence at the trial to clear the Provenzanos and implicate the Mantrangas. That would mean that the Mantrangas, not the Provenzanos, had a motive for the murder.[10] A policeman, a friend of Hennessy, later testified that Hennessy had told him he had no such plans.[11] In any case, it was widely believed that Hennessy's killers were Italian. Local papers such as the Times-Democrat and the Daily Picayune freely blamed "Dagoes" for the murder.[12] Various newspaper accounts of the era linked Hennessy's murder to Esposito and the Mafia.

Aftermath

Hennessy had been popular in New Orleans, and the pressure to catch his killers was intense. The police responded by arresting dozens of local Italians. Eventually 19 men were indicted for the murder and held without bail in the Parish Prison. The following March, nine of the accused men were tried. A series of acquittals and mistrials angered locals, and an enormous mob formed outside the prison the next day. The prison doors were forced open and 11 of the men were lynched. The incident strained U.S.-Italian relations for a time, but was eventually settled with a cash indemnity.[13]

Press coverage of the assassination and lynching was sensational and anti-Italian in tone, and generally would not meet modern journalistic standards. It was almost universally assumed that the lynched men were Mafia assassins who had deserved their fate. Since then, many historians have questioned this assumption.[14][15][16]

On November 24, 1893, John Williams, an African-American, was sentenced to life in prison for the rape of the 10-year-old, Rafael D'Amico. Williams was one of the state witnesses in the Hennessy murder trial. Joseph Shakspeare had ordered the sentence.[17]

Louisiana songwriter Fred Bessel published a bestselling song about Hennessy in 1891, titled "The Hennessy Murder." It begins:

Kind friends if you will list to me a sad story I'll relate,

'Tis of the brave Chief Hennessy and how he met his fate

On that quiet Autumn Evening when all nature seemed at rest,

This good man was shot to death; may his soul rest with the blest.[18]

The lynchings were the subject of the 1999 HBO movie Vendetta, starring Christopher Walken. The movie is based on a 1977 book by Richard Gambino.

References

- Smith 2007, p. 92.

- Smith 2007, p. xiii.

- Gambino 2000, p. 39.

- NY Times 1884.

- Newton 2014, p. 214.

- Nelli 1981, p. 60.

- Gambino 2000, p. 4.

- Smith 2007, p. xxiv.

- Smith 2007, p. 93.

- Botein 1979, p. 264.

- Gambino 2000, p. 76.

- Botein 1979, p. 267.

- Gambino 2000, pp. 95, 126.

- Botein 1979, pp. 263–264, 277, 279.

- Kurtz 1983, pp. 356–357, 366.

- Smith 2007, p. 291.

- Times-Picayune 1893.

- Asbury 2003, p. 412.

Sources

- Asbury, Herbert (2003). The French Quarter: An Informal History of the New Orleans Underworld. Basic Books. ISBN 9781560254942.

- Botein, Barbara (1979). "The Hennessy Case: An Episode in Anti-Italian Nativism". Louisiana History. Louisiana Historical Association. 20 (3): 261–279. JSTOR 4231912.

- Gambino, Richard (2000). Vendetta: The True Story of the Largest Lynching in U.S. History. Guernica. ISBN 9781550711035.

- Kurtz, Michael L. (1983). "Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality". Louisiana History. Louisiana Historical Association. 24 (4): 355–376. JSTOR 4232305.

- Nelli, Humbert S. (1981). The Business of Crime: Italians and Syndicate Crime in the United States. University of Chicago Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780226571324.

- Newton, Michael (2014). Famous Assassinations in World History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610692861.

- Smith, Tom (2007). The Crescent City Lynchings: The Murder of Chief Hennessy, the New Orleans "Mafia" Trials, and the Parish Prison Mob. Lyons Press. ISBN 9781592289011.

- "The New Orleans Exposition; Active Preparations for Its Opening To-day". The New York Times. December 16, 1884.

- "PUNISHABLE BY A LIFE SENTENCE". The Times-Picayune. November 1893.

External links

- "Shot Down at His Door; The Chief of the New-Orleans Police Brutally Murdered"; The New York Times, October 17, 1890

- "Crimes of the Mafias. The Suspected Assassins of Chief Hennessy"; The New York Times, October 20, 1890

- "Indictments Found at Last; The New-Orleans Grand Jury Acts on Chief Hennessy's Murder"; The New York Times, November 22, 1890

- "Chief Hennessy Avenged; Eleven of His Italian Assassins Lynched by a Mob"; The New York Times, March 15, 1891

- "Signor Corte's Farewell; His Story of the Lynching of the Italians"; The New York Times, May 24, 1891

- crescentcity lynchings

- Persico, Joseph E., "Vendetta in New Orleans"; American Heritage Magazine, June 1973