David Cusick

David Cusick (c. 1780 – 1840) was a Tuscarora artist and the author of David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations (1827). This is an early (if not the first) account of Native American history and myth, written and published in English by a Native American.

David Cusick | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1780 |

| Died | c. 1831 or 1840 |

| Nationality | Tuscarora |

| Education | Self-taught |

| Known for | Engraving, illustration, painting |

| Movement | Iroquois Realist Movement |

Biography

Cusick was born between 1780 and 1785, probably on Oneida land in upstate New York.[1][2] He was Tuscarora.[3] His father, Nicholas Cusick (1756–1840), was a Revolutionary War veteran and an interpreter for the Congregationalist mission to the Seneca.[4]: 129 [2] He most likely attended a mission school where he learned to read and write English.[5] David's younger brother, Dennis Cusick, was a watercolor painter, and together the two brothers help establish what the critic William C. Sturvetant has called the Iroquois realist school of painting.[6] David served in the War of 1812,[7] during which his village was burned by the British.

He was a physician,[2] painter, and student of Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) oral tradition. He is thought to have died around 1840.[8]

Book

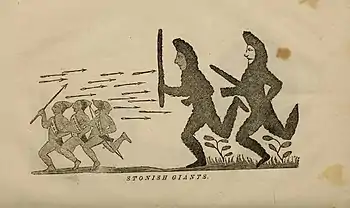

Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations "was the first Native-authored, Native-printed, and Native-copyrighted text" in what is now the United States;[3] Cusick published the first edition of Sketches as a 28-page pamphlet at Lewiston, New York, in 1825[9] or 1827.[1] He re-issued it the following year with additional text and four of his own engravings.[10] The Sketches was republished in 1848[11] and again in 1892. Cusick printed at least some editions with his own money.[12] Sketches was a source for several 19th-century works on Iroquois oral tradition.[13]

Sketches describes about 2,800 years of history.[13] It is divided into three parts. The first part describes Good Mind, who created people called Eagwehoewe. The second describes the Eagwehoewe's experiences with malevolent beings called the Stonish Giants and Flying Heads, among others. Part three is about the Eagwehoewe's creation of a "chain of alliance" with one another.[14]

The narrative begins by describing "two worlds" in existence among the "ancients": a dark "lower world" and an "upper world" inhabited by humans.[15] The narrative describes the twin brothers Enigorio and Enigonhahetgea (the good spirit and evil spirit) and their creatures, the Eagwehoewe (the people) and their enemies the Ronnongwetowanca (giants).[16] The earliest people were championed by the hero Donhtonha and the less heroic Yatatonwatea and plagued by the mischievous Shotyeronsgwea. Other characters include Big Quisquiss, the Big Elk, and the Lake Serpent.[17]

Villains include Konearaunehneh (Flying Heads), the Lake Serpent, the Otneyarheh (Stonish Giants), the snake with the human head, the Oyalkquoher or Oyalquarkeror (the Big Bear), the great musqueto, Kaistowanea (the serpent with two heads), the great Lizard, and the witches introduced by the Skaunyatohatihawk or Nanticokes.[18]

Early critics of Sketches, including Henry David Thoreau, Henry Schoolcraft, and Francis Parkman, dismissed the text. Critic Joshua David Bellin notes that, "considering how rare Sketches was—rare both in numbers and, as the first self-proclaimed history in English by a North American Indian, in kind—the attention, and hostility, it drew are little short of remarkable".[19]

Notes

- Radus 2014, p. 219.

- Sturvetant 2006, p. 45.

- Round 2010, p. 150.

- Sturtevant, William C. "Early Iroquois Realist Painting and Identity Marking." Three Centuries of Woodlands Indian Art. Vienna: ZKF Publishers, 2007: 129-143. ISBN 978-3-9811620-0-4.

- Franklin, Wayne, ed. (2012). "The Iroquois creation story". The Norton anthology of American literature. Vol. A (8th ed.). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 21–25. ISBN 978-0-393-93476-2. OCLC 755080536.

- Sturvetant 2006, p. 44.

- Kalter 2002, p. 11.

- Radus 2014, p. 220.

- Kalter 2002, p. 13.

- Radus 2014, pp. 219–220.

- Round 2010, p. 211.

- Bellin 2001, p. 186.

- Round 2010, p. 210.

- Bellin 2001, p. 202.

- Bellin 2001, p. 201.

- Kalter 2002, pp. 14, 34.

- Kalter 2002, p. 16.

- Kalter 2002, pp. 18, 27.

- Bellin 2001, pp. 183–184.

Sources

- Bellin, Joshua David (2001). The demon of the continent : Indians and the shaping of American literature. University of Pennsylvania Press. doi:10.9783/9780812201222. ISBN 978-0-8122-0122-2.

- Kalter, Susan (2002). "Finding a Place for David Cusick in Native American Literary History". MELUS. 27 (3): 9–42. doi:10.2307/3250653. JSTOR 3250653.

- Radus, D. M. (2014). "Printing Native History in David Cusick's Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations". American Literature. 86 (2): 217–243. doi:10.1215/00029831-2646910. ISSN 0002-9831.

- Round, Phillip H. (2010). Removable type : histories of the book in Indian country, 1663–1880. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-9947-2. OCLC 676700712.

- Sturvetant, William C. (2006). "Early Iroquois realist artists". American Indian Art Magazine. 31 (2): 44–55, 95. hdl:10088/31964. ISSN 0192-9968.

External links

- David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations, 1827 first edition, from Internet Archive.

- David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations, 2006 PDF edition, transposed from the 1828 second edition with modern typography.

- David Cusick’s Sketches of Ancient History of the Six Nations, 1848 edition, from Internet Archive.

- A brief biography by Charles Boewe

- Images of the Library of Congress's copy of the 1828 edition of Sketches