David Goodall (botanist)

David William Goodall AM (4 April 1914 – 10 May 2018) was an English-born Australian botanist and ecologist. He was influential in the early development of statistical methods in plant communities. He worked as researcher and professor in England, Australia, Ghana and the United States. He was editor-in-chief of the 30-volume Ecosystems of the World series of books, and author of over 100 publications.[1] He was known as Australia's oldest working scientist, still editing ecology papers at age 103. Long an advocate of voluntary euthanasia legalisation, he ended his own life in Switzerland via physician-assisted suicide at age 104.

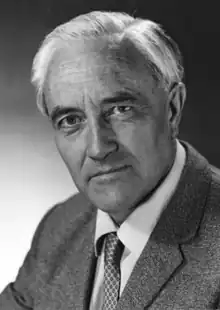

David Goodall | |

|---|---|

David Goodall, early 1970s | |

| Born | David William Goodall 4 April 1914 Edmonton, Middlesex, England |

| Died | 10 May 2018 (aged 104) Liestal, Switzerland |

| Nationality | British Australian |

| Education | Imperial College London |

| Awards | Member of the Order of Australia (2016) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Studies in the assimilation of the tomato plant (1941) |

Early life and education

Goodall was born in Edmonton, Middlesex (now London), England on 4 April 1914 to parents Isabel Blanche (née Harlow) and Henry William Goodall.[2] He was educated at Stationers' Company's School[3] and St Paul's School, London, where an interest in chemistry later turned to biology.[4] Goodall completed his Bachelor of Science degree in 1935 followed by a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1941, both at the Imperial College of Science and Technology, where he was mentored by F. G. Gregory.[3] His PhD research was conducted at East Malling Research Station in Kent on assimilation in the tomato plant.[5] Goodall stated that he was not allowed to join the armed forces during World War II while undertaking his doctorate. He underwent a medical examination for the Royal Navy, but as soon his boss heard of this he refused to release any of his researchers, claiming they were "much more important to the world of agriculture than the war effort".[6]

Research and career

In 1948, Goodall moved to Australia to become senior lecturer of botany at the University of Melbourne. From 1952 to 1954, he served as reader in botany at the then University College of the Gold Coast (now University of Ghana) where he worked in the cocoa industry. He received a Doctor of Science degree from the University of Melbourne in 1953. He then returned to England to take a position as professor of agricultural botany at the University of Reading, which he held from 1954 to 1956. From 1956 to 1967, he was a research scientist at various Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) divisions in Australia. He then moved to the United States, serving as professor of biology at the University of California, Irvine, from 1967 to 1968, and professor of systems ecology at Utah State University from 1968 to 1974. He then returned to Australia and was again affiliated with CSIRO until his formal retirement in 1979.[7]

After retiring, Goodall continued with CSIRO until 1998 as an Honorary Research Fellow in the Division of Wildlife and Ecology, and in 1998 became Honorary Research Associate at the Centre for Ecosystem Management at Edith Cowan University.[7] Over the course of his career Goodall supervised four doctoral and ten masters students, and even into retirement served on the editorial boards of several scientific journals, including Vegetatio and Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics.[3]

Goodall was known for his contributions to plant physiology and ecological statistical analysis. Botanist David Ashton credits him with providing "enormous stimulus" to research in nutritional physiology following World War II.[8] With a series of papers in the 1950s and 1960s titled "Objective Methods for the Classification of Vegetation" he helped turn plant ecology from a descriptive, subjective science into one more quantitative and repeatable.[9] 1954 he was the first to apply factor analysis to community ecology, a process he termed ordination, which is now a widely used term in ecological literature.[10][11] In the late 1960s he co-founded and was director of the Desert Biome project of the International Biological Program, where he organised simulation modelling of processes such as desertification and overgrazing on arid lands.[12]

In 2016, Edith Cowan University declared Goodall, now 102, unfit to travel to his old office on the university's campus,[13] proposed he work from home instead, and allowed him to attend only pre-arranged meetings at the university.[14][13] Goodall stated that he enjoyed talking to colleagues in his office corridor and that he had few social contacts elsewhere in Perth. His daughter warned that the move would have a dramatic impact on his sense of independence and mental well-being and stated "I do not know whether he would survive it".[14] This decision caused an uproar, and the university compromised by relocating him to a new office at its Mount Lawley campus, significantly closer to his home.[15][16]

In December 2016, Goodall was still active at Edith Cowan University[17] and editor-in-chief of the series Ecosystems of the World.[18] At that time, he was thought to be the oldest scientist still working in Australia.[19] Goodall served as editor-in-chief of the 30-volume Ecosystems of the World from its inception in 1972, until its completion in 2005.[20] At age 103, Goodall was still active in his field, editing ecology papers.[21]

Awards and honours

Goodall was promoted to doctor honoris causa at the University of Trieste, Italy, in 1990.[1] He was a member of 14 learned societies, and received the Distinguished Statistical Ecologist Award from the International Association for Ecology in 1994, and the Gold Medal of the Australian Ecological Society in 2008.[22][3] In 1997,he was made an Honorary Member of the International Association for Vegetation Science (IAVS), the organisation's highest award.[23] Goodall turned 100 in 2014,[24] and that year a book of scientific papers organised by the IAVS was dedicated to him.[25] The following year, Goodall was honoured in a special issue of the journal Plant Ecology.[9] In the 2016 Australia Day Honours list Goodall was made a Member of the Order of Australia for "significant service to science as an academic, researcher and author in the area of plant ecology and natural resources management."[26]

Personal life

Goodall was married three times and had four children and 12 grandchildren.[27] When asked why he thought he had managed to reach such a great age, he noted that "genetics helps" but urged "to keep alive, keep active."[4] He played tennis up until the age of 90, and was an amateur poet and actor, performing with a Perth theatre group.[28][29]

Death

Goodall advocated for the legalisation of voluntary euthanasia, being a member of assisted dying advocacy group Exit International for over twenty years.[28] His death in 2018, at the age of 104, was an assisted suicide.[30]

Carol O'Neill, a representative from Exit International, said Goodall's health had affected him greatly. She explained that it came at a time when he was also forced to give up driving and performing in theatre. He just didn't have the same spirit and he was packing up all his books. Goodall's decision to end his life was hastened by a serious fall in his one-room apartment. He was only found by the cleaner two days later. Doctors called for around-the-clock care, or that he be moved to a nursing home.[31]

On 30 April 2018, Goodall announced his plans to end his own life the following month with the aid of physicians in Switzerland. During the signing of paperwork in the Swiss clinic, David Goodall was questioned about his health and he stated "I'm not ill. I want to die," he insisted.[32]

The business class flight tickets to Europe, for himself and his helpers, were financed by crowdfunding via the website GoFundMe, where 376 donors exceeded the target of A$20,000.[33] He stated, "I don't want to go to Switzerland, though it's a nice country. But I have to do that in order to get the opportunity of suicide which the Australian system does not permit. My feeling is that an old person like myself should have full citizenship rights including the right to assisted suicide."[34]

Goodall travelled first to France to visit family, and then to Liestal, Switzerland, where two doctors cleared him to proceed with his assisted suicide,[35] although he was not terminally ill. In Switzerland, Exit International organised a press conference during which Goodall answered journalists' questions and sang the first few lines of the fourth movement of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, based on Friedrich Schiller's poem Ode to Joy, in German.[36]

Professor David Goodall ended his life on 10 May while listening to Beethoven's Symphony No. 9. Surrounded by his family, Goodall pushed a lever that set in motion the lethal injection of Nembutal.[30][37] He woke up shortly after a failed attempt to administer the drug and said: "Oh, it's taking rather a long time." After successfully pushing the lever, he then closed his eyes and passed away while being in the presence of his family.[32]

References

- Mucina, Ladislav; Podani, Janos; Feoli, Enrico (2018). "David W. Goodall (1914-2018): An ecologist of the century". Community Ecology. 19 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1556/168.2018.19.1.10.

- "Goodall, David William". Who's Who in America, 1978/1979 (40th ed.). Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1978. p. 1239. ISBN 0837901405.

- Clifford, H. Trevor (2015). "David Goodall - Multiple decades devoted to the service of ecological knowledge, a whole century devoted to the enjoyment of life" (PDF). Tropical Ecology. 56 (1): 133–135.

- Hooper, Rowan (21 December 2016). "Australia's oldest working scientist speaks about his life". New Scientist.

- Goodall, David William (1941). Studies in the assimilation of the tomato plant (PhD thesis). University of London (Imperial College of Science and Technology).

- Gartry, Laura (10 May 2017). "David Goodall: Australia's oldest working scientist fights to stay at university". ABC.

- Alafaci, Annette (7 February 2011). "Goodall, David William (1914– )". Encyclopedia of Australian Science.

- Ashton, David H.; Ducker, Sophie C. (1992). "John Stewart Turner 1908-1991". Historical Records of Australian Science. 9 (3): 278–290. doi:10.1071/HR9930930278.

- Minchin, Peter R.; Oksanen, Jari (2015). "Statistical analysis of ecological communities: progress, status, and future directions". Plant Ecology. 216 (5): 641–644. doi:10.1007/s11258-015-0475-7. S2CID 18386641.

- Pierre Legendre; Louis Legendre (2012). Numerical Ecology. Elsevier. pp. 425–. ISBN 978-0-444-53868-0.

- Timothy F. H. Allen; Thomas W. Hoekstra (2015). Toward a Unified Ecology. Columbia University Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-231-53846-6.

- Coleman, David C. (2010). Big Ecology: The Emergence of Ecosystem Science. University of California Press. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-520-26475-5.

- Hamlyn, Charlotte (20 December 2016). "WA university reverses decision to eject 102-year-old scientist from campus". ABC News. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Hamlyn, Charlotte (20 August 2016). "102 year old researcher told to leave university post". ABC News. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Australian Associated Press (21 December 2016). "Australia's oldest scientist, 102, given new office on Perth campus". The Guardian.

- Agence France-Presse (30 April 2018). "David Goodall: 104-year-old scientist to end own life in Switzerland". The Guardian. Sydney. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Professor David Goodall". ecu.edu.au. Edith Cowan University. 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- Goodall, David W. (1977). Ecosystems of the World. Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 9780444417022.

- "Australia's oldest working scientist wins battle over office". bbc.co.uk. London: BBC News. 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016.

- Centre for Ecosystem Management: 2005 Report (PDF) (Report). Joondalup, WA: Edith Cowan University, School of Natural Sciences.

- "David Goodall, 103 years-old and still working". Daily Telegraph. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2018.

- Patil, G. P. (1995). "Silver Jubilee of Statistical Ecology Around the World". Coenoses. 10 (2/3): 57–64. JSTOR 43461318.

- "Honorary Members". International Association for Vegetation Science. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Staff (4 April 2014). "Celebrating a century". ecu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Mucina, Ladislav; Price, Jodi N.; Kalwij, Jesse M., eds. (2014). Biodiversity and Vegetation: Patterns, Processes, Conservation (PDF). Perth: Kwongan Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9584766-5-2.

- "Australia Day Honours 2016: the full list". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 2016.

- AFP (10 May 2018). "David Goodall gives last press conference before euthanasia". The Australian.

- Hamlyn, Charlotte (3 April 2018). "Academic David Goodall turns 104 and his birthday wish is to die in peace". ABC News. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Scheuber, Andrew (10 May 2018). "David Goodall – tributes to 104 year old botanist and alumnus". Imperial News. Imperial College London.

- Agence France-Presse (10 May 2018). "104-year-old Australian scientist dies after flying to Switzerland to end his life". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- "David Goodall: Australian scientist, 104, ends life 'happy'". bbc.co.uk. London: BBC News. 2018.

- Charlotte, Hamlyn (12 July 2018). "David Goodall's final hour: An appointment with death". ABC News. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- "Help David Go to Switzerland". gofundme.com. London: GoFundMe. 2018.

- 104-year-old academic David Goodall to travel to Switzerland for voluntary euthanasia, Charlotte Hamlyn, ABC News Online, 2018-05-01

- "How scientist spent his last day". NewsComAu. 9 May 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- Bachmann, Helena (10 May 2018). "David Goodall, 104, takes final journey at Swiss assisted-suicide clinic". UA Today. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- Noyes, Jenny (10 May 2018). "Australian scientist David Goodall dies after lethal injection". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

External links

- Official webpage Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Collecting localities and biography from Australian National Botanic Gardens

- David W. Goodall at JSTOR Plant Science