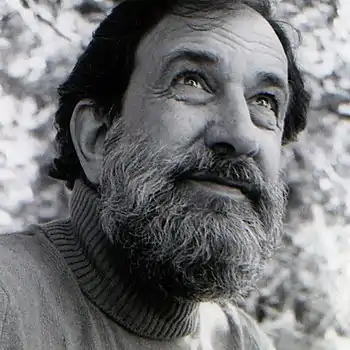

David Kherdian

David Kherdian (born 1931) is an Armenian-American writer, poet, and editor. He is known best for The Road from Home (Greenwillow Books, 1979), based on his mother's childhood—cataloged as biography by some libraries, as fiction by others.[1]

David Kherdian | |

|---|---|

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Armenian American |

| Notable awards | 1979 Boston Globe–Horn Book Award for children's nonfiction,[1]. The only runner-up for the 1980 Newbery Medal,[10] recognizing The Road from Home (1979). |

| Spouse | Nonny Hogrogian |

Biography

David Kherdian (ker.de.en) born December 17, 1931 in Racine, Wisconsin to Veron Duhmejian (1908 - 1981), and Melkon Kherdian (1891 – 1958). His sister, Virginia (1943 - ). Both parents were survivors of the Armenian Genocide.

An Armenian-American poet, novelist, and biographer, founder of three small presses and editor of three journals: Ararat: A Quarterly, Forkroads: A Journal of Ethnic-American Literature, and Stopinder: A Gurdjieff Journal for Our Time. His wife, Nonny Hogrogian, a painter and award-winning children's book illustrator, was the art director for each of the presses and journals. She also illustrated many of his books, and provided nearly all of his book titles. He liked to refer to her as his Senior Editor, while evoking the Armenian word, Garavel, that doesn't exist in the English language: the one who civilizes, which provision too often falls on mothers and wives—wives in particular. For two years they lived in Lyme Center, New Hampshire, where he was the state "poet-in-the-schools". The state university library is one repository for their works (in a joint collection).[2] Hogrogian has illustrated some of his books, both poetry anthologies edited by Kherdian and his own writings.[3]

Kherdian's reputation is spread over all the genres he has worked in, from his many books, to the three journals he edited, as well as his three small presses he founded. He was the first to place ethnic-American writers within the canon of American literature, which he accomplished through anthologies and journals, and just as importantly with his own writings. As an editor, writer, and publisher, Kherdian has always been ahead of his time; he comes down the long intermittent line of mystic American poets, namely, Walt Whitman, Henry Thoreau, and Emily Dickinson—poets who are rarely valued in their lifetimes.[4]

Permanent collections of Kherdian's work can be found in five places, University of Connecticut Special Collections,[5] Heritage Museum, Racine, Wisconsin,[6] University of New Hampshire Library, University of Wisconsin - Parkside, James L. Henry Collection - Bancroft Library, Berkeley California.

Early years

Kherdian's Midwestern childhood typically revolved around athletics, at which he excelled: basketball, football, and baseball, but his real athletic passion came later, when he took up golf, and quickly became a low handicapper.

His troubled school years were marked by racist teachers who held him back. He would transform their effects on him through his poems, memoirs and prose fiction. In 2017 he published Starting From San Francisco: A Life In Writing, where he wrote about his school years without rancor, although he had earlier termed his grade school years an incarcerated hell. He dropped out of high school during the first semester of his junior year. After his Army service he graduated from the University of Wisconsin with a B.S. Degree in philosophy.

Kherdian was driven to know himself, feeling an urgency to get the first twelve years of his life understood and reconciled, in order to become an adult. "All of these notions, I knew, had kept me from writing, but little by little, principally through a gradual understanding of Saroyan's work, I saw that for the purposes of art one life is as good as another, and that no life is unworthy of the attention of art."[7]

From his earliest years he was a library habitue. One classmate recalled that he had set a record for book reports in the 7th grade. It was then he discovered the writings of James Willard Schultz, the squaw man who was the first white man to penetrate the Blackfeet Nation, later to become a famous children's book author with tales from his years with the Blackfeet tribe. Earlier, Kherdian's mother, who taught Armenian language classes in the church basement, brought home a drawing by one of her students of a Native American, that her son adored, inspiring his own artistic skills.

Drawing and reading were the two activities that dominated his adolescence, precluding his life as a writer, which he would prize additionally for the solitude it provided, being a loner both by temperament and defense against discrimination.

Kherdian was nineteen when he read Theodore Dreiser's The Stoic, and realized that there existed another way of being in life, which prompted him to pursue writing as a means toward an ideal goal. At that time he was on the road as a door to door magazine salesman where he experienced a camaraderie on a scale higher than school sports; the memory of this would carry him through his embittered army experiences, having narrowly escaped court martial when he went AWOL for the thirteen day journey aboard a troop ship to Korea.

He would continue his resistance to authority, a pattern begun in elementary school, and continued as an artist contemptuous of academia, and eschewing all factions, fashions, and movements in literature. His instinctive aim throughout his life was to fight for his own individuality, which led him eventually to the spiritual teaching of G. I. Gurdjieff.

His childhood was typically Midwestern. He grew up beside Root River, on the shores of Lake Michigan, enshrining both in his writings. These two bodies of water, along with the natural world around him became the reconciling forces that effectively contravened the unhappy circumstances of his childhood.

In Racine, only those primarily of European ancestry were acknowledged Americans, while Jews, African-Americans, Mexicans, Armenians and Italians were known by their ancestral race only. Racine was a backward, backwater factory town of 65,000 during Kherdian's childhood. What preserved him from its stultifying influences were the nearby fields and streams, the library, athletics, and also his fierce rebellious nature.

The trauma of living in a society that was antithetical to his very nature and temperament left him with resentments that impelled him in his early sixties to write Asking the River, achieving through forgiveness liberation from his painful past. But it was only in his much later book, Factory Town: A 20th Century Memoir, where the good and the bad in his hometown were conjoined, for him to acknowledge the ample goodness that had been there all along.

Through the transformative achievements he gained from his inner struggles, he would secure his destiny and create his own world, boldly stating in his memoir, Starting From San Francisco, "I had unwittingly transformed the material that surrounded me as a child into something meaningful, instructive, and enlightening for myself." Further, on speaking of places and in particular the people of his childhood, he wrote, "There was a meaning to their lives for me. It was so because I required it, and because I did they would become what they needed to become for me."[4]

The river had been his great solace, comforter and teacher. When asked to describe its meaning for him (in the film, The Dividing River / The Meeting Shore), he replied that it stood for time, movement, truth, change and eternity—he saw moving water as the power that carries man into this life as well as the force that impels a continuing journey toward our ultimate destiny, as evolving immortal beings.

Kherdian credited the three large Kaiserlian families (comprising ten children in all) as his first literary influences during his childhood years. His best friend, Mikey Kaiserlian was the subject of The Dividing River / The Meeting Shore,[8] elegiac poems in his honor following his friend's untimely death. Mikey, and his cousin Ardie were Kherdian's closest friends in childhood, appearing frequently in his poems, memoirs, and stories. Maggie, the oldest of all the Kaiserlian children, became Kherdian's confidant, and appeared in that role as Lily in his autobiographical novella Asking the River. Their homes for him were islands of culture and sophistication in a backward malodorous, factory town, and together they were his sole guides in opening him to the influences that formed his outlook on life, introducing him to jazz, live theatre, good books and foreign movies. As the youngest among them their hold on his imagination was unique and everlasting.[8]

Career

Kherdian's spiritual nature, previously revealed in his closeness to nature, and his talent for drawing, did not come to fruition until he began writing poetry at age 35, when in his early book, Looking Over Hills, he broke through to another dimension of reality that would be a guide for his future work. The great majority of these poems were written in a period of one month on his first visit to the Berkshires of Massachusetts in the summer of 1970, when he "realized that the higher states in which poets often find themselves when writing do not belong to them, cannot be beckoned at will, and in fact, the poet at such times is nothing more than a radio transmitting messages between levels of reality."[9]

Kherdian moved from the Berkshires to New York City to take the editorship of Ararat: A Quarterly, Armenian-American literary journal to which he had long contributed poems, reviews, and articles. He soon met his soul mate, Nonny Hogrogian, who became his art director, collaborator and lifelong mate. It was not long after that he became acquainted with the writings of the mystic G. I. Gurdjieff, whose teaching he would follow for the rest of his days. Following nine years in a Gurdjieff school in Oregon, where he wrote several books of poetry—he later summed up his journey in his memoir, On a Spaceship with Beelzebub: By A Grandson of Gurdjieff (Beelzebub was the fallen angel in Gurdjieff's opus, All and Everything).

If Theodore Dreiser's novel had opened Kherdian's eyes to another world, Carlos Castaneda had shown him what that world might look like, when continuing search led him to the Greek-Armenian mystic, G. I. Gurdjieff. Soon after the Kherdians moved to Oregon to enter a spiritual school called The Fourth Way, which was the name Gurdjieff gave to his teaching, that would in time spread across the globe, in particular his sacred dances called Movements, choreographed with music by Gurdjieff.

Kherdian at first feared that the spiritual influence he had put himself under would in some way threaten his creativity, but instead it slowly, dramatically enhanced its evolution, as would become evident with his retelling of Monkey: A Journey to the West, a Buddhist allegory, that he followed with his narrative biography titled, The Buddha, The Story of an Awakened Life.

The first book he wrote after leaving his school in Oregon was The Dividing River / The Meeting Shore, now considered his finest work in poetry, but it was his later book, Letters to My Father, that Kherdian favored among his many books of poetry.

Upon graduating from the University of Wisconsin in January, 1960, he moved to San Francisco, a life changing experience, where he could write openly with other already established, and aspiring writers like himself. He began friendships with Philip Whalen, David Meltzer, William Everson (Brother Antoninus), Richard Brautigan, Allen Ginsberg, and others, but most importantly, William Saroyan, who would soon become his mentor and good friend.

Following publication of his first book, A Bibliography of William Saroyan:1934-1964 he was approached by a New York editor to do bibliographies of some Beat poets. This would result in his second book, Six Poets of the San Francisco Renaissance: Portraits and Checklists. The mesmerizing influence of William Saroyan was so powerful and overwhelming, that it was only after the completion of his Saroyan bibliography that he was finally liberated to write from himself.

Kherdian's long apprenticeship was detailed in his memoir, Starting From San Francisco: A Life in Writing. Although his writing came to fruition in San Francisco, it had begun, many years earlier, when he read the short stories of William Saroyan. Although they were both first generation Armenian-Americans, Saroyan was a generation older, and grew up in Fresno, a city where Armenians were a dominant presence, unlike Racine, where there were but 200 Armenian families during Kherdian's childhood. What he and Saroyan had in common, however, was their near obsession with their own biographies, that served as their primary literary material for each of them.

Shortly after leaving San Francisco for Fresno, Kherdian founded The Giligia Press, where he published his second book and also his first book of poems, On the Death of My Father and Other Poems, that Saroyan would title and write an Introduction for, calling the title poem one of the best lyric poems in American poetry.

A short-lived marriage followed, that coincided with and inspired an outpouring of poetry, of which he wrote he stated in his memoir: "There is a reason why poetry, love, and youth are connected in our minds. Perhaps one has to be mad to write poetry, and being in love makes this madness seem desirable." He then published Down at the San Fe Depot: 20 Fresno Poets, dedicating the book to Philip Levine, with whom Kherdian had made a friendship, while working in special collections at Fresno State College, where Levine taught most of the poets in the anthology. Down at the Santa Fe Depot had an electrifying effect on poetry, resulting in numerous regional anthologies, and a burgeoning of small presses around the country. Also, during this same period, Kherdian taught a class on Beat poetry, for the first time in an American college or university.

During the Kherdians nine years in the Gurdjieff school in Oregon, called The Farm, they established Two Rivers Press, where they learned to set type and print by letterpress, binding their books by hand on fine papers, which included their own hand marbled endpapers. Kherdian also began what he called Writing Classes, combining the gains made from his own writings with the principles of the Gurdjieff teaching, in a method that would liberate those who had formed patterns in their childhood that constricted their growth.

During this period Kherdian's best known book, The Road from Home was published, which won numerous awards before being translated, published and pirated around the globe. He was now working in a variety of genres: fiction, biographies, memoirs, children's books, and also translations and retellings, including the Armenian bardic epic, David of Sassoun, told in a series of genealogical tales covering five generations.

Anthologies

In the early 1970s the Poets in the Schools project was established, with Kherdian named for New Hampshire, where the Kherdian's were living in their first home. During this period he published with Macmillan a series of three anthologies on contemporary American poetry: Visions of America: By the Poets of Our Time, and Traveling America: With Today's Poets, as well as Settling America: The Ethnic Expression of 14 Contemporary American Poets, which was the first such anthology to be published in America. During his class visits he realized that contemporary American poetry was being neglected in schools, so he followed his earlier anthologies, that were aimed at YA markets, to concentrate on the earlier grades, resulting in Poems Here and Now, The Dog Writes on the Window with His Nose, If Dragon Flies Made Honey, and his own Country Cat; City, Cat.

He would eventually follow with two projects close to his heart: Forkroads: A Journal of Ethnic-American Literature, and then later Forgotten Bread: First-Generation Armenian American Writers—an idea he had carried on in his head for forty years, that would knit together the first generation of Armenian-American writers—the first being three writers from Armenia, who came to America and wrote in English— with the next generation, being the first born in America. Prominent writers from the next generation were selected to write profiles for the writers that came before them.

The undisclosed purpose of the journal Forkroads, was to create one world through stories from many different cultures—to build respect and understanding, with an abiding love and openness he believed would inevitably grow out of this.

His aim for Forgotten Bread was to reveal how each particular ethnic group had brought to American literature its own sensibility, strength and wisdom, with its results embodied in American literature, not as a hybrid but as a new and unique literature able to speak for itself.

Kherdian has been credited through his anthologies, his journal Forkroads, and also through his small press with establishing ethnic American literature into the American canon.

Armenia

Kherdian was drawn to his heritage, not only to be informed of his own ancestry, but to seek influences that he needed to examine for himself, in order to evolve both as a man and as an artist. Not having grandparents he needed to find his own way back, and not only through his own bloodline, but from racial memory.

The Kherdians were invited to Armenia to do a special issue on the arts and life in Armenia for Ararat, the journal they were editor and art director for at the time. They met with the famous Armenian artist, Martiros Saryan, and spent an evening in the home of Yervant Kotchar, celebrated sculptor of David of Sassoun, which stands in a notable square in Yerevan, Armenia. Kotchar at the close of their visit asked to read Kherdian's palm, and quickly exclaimed, “You must go home at once, you have important work to do.“ At that point Kherdian had produced but two books of poems, but Kotchar could apparently see the future body of Kherdian's work—perhaps even that his retelling of David of Sassoun would make Armenia's great epic known in the West.

Upon his return to America Kherdian co-translated a small book of poems by Charentz, Armenia's greatest poet of the 20th century. Later he transfigured traditional songs into poetry for a collection, titled, The Song of the Stork: Early and Ancient Armenian Songs.

In time Kherdian would absorb, transform and transcend many of the inhibiting conditions of his own culture, together with the racial predispositions passed down to him, to achieve liberation from all the elements and factions that would impede his spiritual awakening and growth, while he also enshrined with his art some of the many achievements of his ancestral race.

Awards

Kherdian won the 1979 Boston Globe–Horn Book Award for children's nonfiction,[10] and he was the only runner-up for the 1980 Newbery Medal,[11] recognizing The Road from Home (1979), about the childhood of his mother Veron Dumehjian before and during the Armenian genocide. The book has been published in most European countries and in many other places, including Japan.[12] It has been reissued several times in the United States and is increasingly read in middle schools throughout the country. In the sequel Finding Home (1981) she settles in America as a mail-order bride. It too is sometime cataloged as fiction.[13]

Selected works

WorldCat member libraries report holding more than 20 books by Kherdian, of which The Road from Home is by far the most common.[14]

- A Bibliography of William Saroyan, 1934–1964 (1964)

- Six Poets of the San Francisco Renaissance: Portraits and Checklists (1967)

- Homage to Adana (1970)

- Visions of America (1973)

- Settling America: The Ethnic Expression of 14 Contemporary Poets (1974)

- Poems Here and Now (1976)

- Traveling America with Today's Poets (1977)

- The Dog Writes on the Window with His Nose and Other Poems (1977)

- The Road from Home (1979) – biography in some library catalogs, fiction in others[1]

- Finding Home (1981) – continues The Road from Home[13]

- The Song in the Walnut Grove (1982) (Illustrated by Paul O. Zelinsky)

- Right Now (1983)

- The Animal (1984)

- Root River Run (1984)

- Bridger: The Story of a Mountain Man (1987)

- A Song for Uncle Harry (1989)

- The Cat's Midsummer Jamboree (1990)

- Feathers and Tails: Animal Fables from Around the World (1991)

- On a Spaceship with Beelzebub: By a Grandson of Gurdjieff (1991)

- Lullaby for Emily (1995)

- Beat Voices: An Anthology of Beat Poetry (1995)

- The Rose's Smile: Farizad of the Arabian Nights (1997)

- The Golden Bracelet (1997)

- I Called it Home (1997)

- The Neighborhood Years (2000)

- Come Back, Moon (2013)

- Starting from San Francisco: A Life in Writing (2017)

- On the Death of my Father and Other Poems (1968)

- Down at the Santa Fe Depot: 20 Fresno Poets

- Looking Over Hills (1972)

- The Nonny Poems (1974)

- Any Day Of Your Life (1977)

- Poems Here and Now (1976)

- Country, Cat; City, Cat (1978)

- I Remember Root River (1981)

- If Dragon Flies Made Honey (1977)

- The Farm (1978)

- The Farm: Book 2

- The Pearl: Hymn Of The Robe Of Glory (1979)

- It Started With Old Man Bean(1980)

- Finding Home (1981)

- Beyond Two Rivers(1981)

- Pigs Never See The Stars: Proverbs From The Armenian(1982)

- The Mystery Of The Diamond In The Wood(1983)

- Place of Birth(1983)

- Right Now(1983)

- Threads Of Light(1985)

- The Great Fishing Contest(1991)

- The Dividing River / The Meeting Shore(1990)

- Monkey: A Journey To The West(2005)

- Asking The River(1993)

- Juna's Journey(1993)

- By Myself(1993)

- Friends: A Memoir(1993)

- My Racine(1995)

- Chippecotton: Root River Tales Of Racine(1998)

- The Revelations Of Alvin Tolliver(2001)

- Seeds Of Light: Poems From A Gurdjieff Community(2002)

- Letters To My Father (2004)

- The Song Of The Stork: And Other Early And Ancient Armenian Songs(2004)

- The Buddha: The Story Of An Awakened Life.(2004)

- Yeghishe Charentz: 13 Poems - Translated by David Kherdian and Garig Basmadjian

- Finding Theodore Czebotar(2009)

- Nearer The Heart(2006)

- Forgotten Bread: First Generation Armenian American Writers(2008)

- Gatherings: Selected And Uncollected Writings(2011)

- Living In Quiet: New & Selected Poems(2013)

- Come Back, Moon(2013)

- David Of Sassoun: An Armenian Epic(2014)

- A Stopinder Anthology, edited by David Kherdian (2015)

- Root River Return(2015)

- A Stopinder Anthology. Volume 2

- Factory Town: A 20th Century Memoir (2017)

- Blackfoot / Whitefoot: The Life Of James Willard Schultz (2018)

References

- See WorldCat member records of The Road from Home for example: Biography, OCLC 4492330; FictionOCLC 438300821. WorldCat does not identify catalog sources but the former is an English language record ("238 pages") and the latter is not ("238 str."). Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- "Nonny Hogrogian and David Kherdian: Papers, 1966–1986". Milne Special Collections. University of New Hampshire. Retrieved June 26, 2013. With biographical sketch.

- "Nonny Hogrogian Papers". de Grummond Children's Literature Collection. University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved June 26, 2013.. With biographical sketch.

- Kherdian, David (May 8, 2020). Becoming A Writer. Cascade Press. ISBN 978-1948730938.

- "Home | UConn Library". November 24, 2014.

- "Home". racineheritagemuseum.org.

- Starting from San Francisco

- Kherdian, David (December 1990). The Dividing River. ISBN 978-0936385013.

- Starting from San Francisco: A Life in Writing

- "Boston Globe–Horn Book Awards: Winners and Honor Books 1967 to present". The Horn Book. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

-

"Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 1922–Present". ALSC. ALA.

"The John Newbery Medal". ALSC. ALA. Retrieved June 26, 2013. - Soghomonian, Sarah (May 2005). "Authors David Kherdian and Nonny Hogogrian Speak on Campus" (PDF). Hye Sharzhoom. 26 (4): 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2014.

- See WorldCat member records of Finding Home for example: Biography OCLC 6789278; Fiction OCLC 764698736. These records seem to be from English-language libraries. Retrieved 2015-01-31.

- "Kherdian, David". OCLC WorldCat Identities. WorldCat (worldcat.org). Retrieved October 25, 2014.

External links

- Official website

- David Kherdian at Library of Congress, with 56 library catalog records