David Manson (schoolmaster)

David Manson (1726-1792) was an Irish schoolmaster who in teaching children basic literacy sought to exclude "drudgery and fear" by pioneering the use of play and peer tutoring. His methods were in varying degrees adapted by freely-instructed hedge-school masters across the north of Ireland, and were advertised to a larger British audience by Elizabeth Hamilton in her popular novel The Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808).

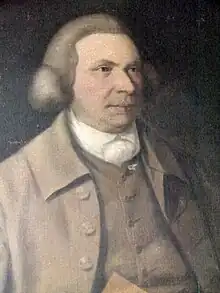

David Manson | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Joseph William 1783, Royal Belfast Academical Institution | |

| Born | 1726 |

| Died | 1792 |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Schoolmaster in Belfast. Inventor. |

| Known for | Teaching in accord with "the principle of amusement". Phonetic approach to basic literacy. |

| Notable work | A New Pocket Dictionary; Or, English Expositor (1762) |

Patronised by leading, reform-minded, families, his school in Belfast counted among its pupils the future pioneering naturalist John Templeton, the radical humanitarian Mary Ann McCracken and her brother Henry Joy McCracken, the United Irishman, who was to hang for his role in the 1798 Rebellion.

Early life and education

Manson was born in 1726 at Cairncastle, County Antrim, son of John Manson and Agnes Jamison. At the age of eight he contracted rheumatic fever which affected him for the rest of his life. Because of this he was schooled at home by his mother, and to a level of proficiency that allowed Manson to advertise himself as an English scholar.[1]

Manson began teaching on the north Antrim coast, holding his first school in a byre or cow house, and serving the Shaws of Ballygally Castle (where for many years an apartment was known as the "David Manson" room) as a family tutor.[2] Inspired by the "mild manner of his mother's instruction" Manson began to develop the principles of his future pedagogy, finding opportunities for children to learn even as he played with them.[1]

Later, he improved himself in writing, arithmetic and "the rudiments of the Latin" in the school of the Reverend Robert White in Larne.[1] Biographers of a later pupil of White's, William Steel Dickson, suggest that, having gone through the "almost useless routine of Irish country schools", Dickson was first taught "to think" by the Larne schoolmaster.[3] With other Presbyterian ministers of his generation, it is possible that White had studied either at an academy in Dublin or at the University of Glasgow with "the father of the Scottish Enlightenment", Francis Hutcheson.[4] Writing of children, Hutcheson stressed their kindness and sense of fairness and justice and he called for education that avoided rigid learning and harsh punishment.[5] White's Glasgow-trained son, John Campbell White, (later with Dickson, a United Irishman) was himself to be an education reformer, helping establish a Free School for poor children in Belfast.[6][7]

An opportunity to teach mathematical navigation induced Manson to cross the Irish Sea to Liverpool, but his mother's illness and an attachment to a Miss Linn, his future wife, soon called him back. From 1752, Manson was settled in Belfast.[8]

Manson's English Grammar "play school"

In order to support himself and his wife, Manson started a small home brewery. Mary Ann McCracken recalls her uncle Henry Joy, proprietor of The News Letter, turning to Manson for "a mug of ale and long discussions" not only of politics, but also of education.[9] Recording his life in 1811, William Drennan in his Belfast Monthly Magazine noted that Manson "never allowed the desire of founding a play school, which was to be taught on the principle of amusement" to "depart from his mind".[1]

Accepting only those who had not been taught the alphabet, in 1755 Manson started an evening school at his house in Clugston's Entry. He advertised his ability, at moderate cost, to teach children to read and understand the English tongue "without the discipline of the rod by intermingling pleasurable and healthful exercise with their instruction".[9]

The school taught girls and boys together, with Henry's Joy's eldest child, Elinor, then about six years old, among the first pupils. Children from other prominent mercantile families in the largely Presbyterian town followed including, in time, John Templeton (Ireland's pre-eminent naturalist)[10] James MacDonnell (polymath and "father of Belfast medicine"),[11] and the siblings Mary Ann, and Henry Joy, McCracken. (In 1788, the McCrackens attempted their own school for the poor, but it was quickly closed down by the town's increasingly unnerved Anglican establishment for its indifference to sabbatarian and sectarian sentiment.[12][13] Ten years later, having led United Irish forces into the field against the Crown at Antrim, Henry Joy was hanged outside his former schoolroom in the High Street Market House).[14]

Such was the success of the school that in 1760 Manson moved it to larger premises (also) in High Street, where he accommodated boarders, and eight years later to a still larger, purpose-built schoolhouse in the new Donegall Street (where today he is commemorated by an Ulster History Circle Blue Plaque).[15] Manson also started a night school, offering free instruction in his methods to any school teacher who would attend.[16]

Promoted by Elizabeth Hamilton

It is unlikely that Elizabeth Hamilton, one of the most noted female writers of her day, attended Manson's school unless briefly before leaving Belfast for Scotland in 1762 at age six. But her elder sister Katherine had done so, and she was well acquainted with his methods.[8] They occasioned a lengthy discourse on child education in Hamilton's best-known work, The Cottagers of Glenburnie (1808).[17] The fictional Mr Gourley directs the village teachers Mrs Mason and Mr Morrison's in reorganising their school on a spare-the-rod monitorial system. He cites David Manson's account of "what he calls his play school; the regulations of which are so excellent, that every scholar must have been made insensibly to teach himself, while he all the time considered himself as assisting the master in teaching others".[18][19]

In a footnote Hamilton assures the reader that she does not intend to "detract from the praise so justly due" to the educational reformer Joseph Lancaster (1778-1838), but observes that in "some of his most important improvements, [had] been anticipated by the schoolmaster of Belfast". Manson's "extraordinary talents" had been "exerted in too limited a sphere to attract attention".[18]

Child-centered pedagogy

Hamilton's praise for Manson was consistent with her admiration for his younger contemporary, the renowned Swiss pedagogue Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi.[20] Yet while Manson's co-operative and meritocratic system of "sensory, logical and child-orientated"[21] education may have foreshadowed some of the experiments usually ascribed to a new school of educationalists inspired by Rousseau,[22] there is no evidence that he was influenced by Continental theorists.[23] What is suggested is that John Locke's child-centred pedagogical theories "set the terms by which education was debated in eighteenth century Ireland", and that, consciously or not, Manson's pedagogy was "an exemplar of the Lockean approach".[21][24]

Discipline and play

The description Hamilton offers through "Mr.Gourley" of Manson's disciplinary scheme[18] is consistent with that provided by William Drennan. In the classroom Manson mimicked the hierarchy of adult society. The boy and girl who excelled at their morning lessons were appointed the king and queen while others were nominated, with various titles, as members of the "royal society" according to their academic performance and ability to repeat lines of grammar. Further down the academic ranking were the pupils who could only remember a small number of lines and were designated as tenants and under-tenants, and below them the triflers and sluggards. The rent or tribute paid to rank was a certain portion of reading or a spelling lesson, so that to receive their due one child might be induced to assist another. On Saturdays, when there was no formal class, the king and queen had the privilege of calling a parliament to settle accounts.[1][25] Unlike the hierarchy to which their families were subject in the adult world, the ranking of the pupils within the school was not fixed and, other than by regard, was not enforced.

The key to Manson's scheme, according to Drennan, was the "liberty of each to take the quantity [of lessons] agreeable to his inclination".[1] When, after 18 months he had collected some 20 scholars and was sufficiently confident, Manson admitted children to the school "who had contracted an aversion to their books because they had been forced to them, by severe correction". His method was to pay them seemingly little attention at first. The disaffected novices were allowed to "enter cheerfully and heartily into the amusements of the school" without being forced to attend classes or to read. Seeing "the honours conferred on children who paid attention to their books", and conversely the "disrespect due to such as were ignorant, and consequently inattentive", in time the new pupils would themselves "request the favour of a lesson".[1]

Manson's overriding commitment was to banish "drudgery and fear [...] from places of junior education",[1] by emphasising choice instead of coercion; and encouragement instead of punishment.[2][26] Thus, for Manson "knowledge, diligence and sobriety are not sufficient qualifications" in a teacher. There has to be the "patience, benevolence and a peculiar turn of mind by which [he] can make a course of education an entertainment to himself as well as to the children".[27]

Co-education

In terms of female education, Manson's English Grammar School was the most important establishment in Belfast.[28] It has been compared with the leading, and contemporaneous, co-education establishment in Dublin, the English Grammar School of Samuel Whyte, who, with Locke, similarly believed that, for girls and boys alike, education should be engaging and enjoyable.[24]

In Hamilton's fictional school, the poor village girls and boys are in separate classes, and in applying Manson's principles Mrs Mason encounters greater difficulty than does Mr. Morrison. Considering the "business of housework" not merely "useful to girls in their station as an employment" but also "a means of calling into action their activity and discernment", she sets them the task of cleaning the school rooms. On Saturday, those who excel have "the honour" of polishing the furniture in her parlour".[29] No record of the Belfast school suggests this is based on Manson's own experience or practice.

There may be a question of social class, but Drennan makes a point of remarking that in Donegall Street, "Young ladies received the same extensive education as the young gentlemen".[1] They moved together in equal rank through the common play hierarchy: queens alongside kings, duchesses alongside dukes, and ladies alongside lords. Girls as well as boys sat in the Saturday parliament and took the role of chancellor and vice chancellor.[30][31]

Manson's dictionaries and primers

Hamilton believed that "a small volume, containing an account of the school, rules of English grammar and a spelling dictionary" is "the only memorial left" of Manson.[18] A New Pocket Dictionary; Or, English Expositor (Belfast: Daniel Blow, 1762) included notes on "The Present State and Practices of the Play-School in Belfast"[32] and, as described by Drennan, contained "tables from monosyllables to polysyllables" so arranged as to emphasise the "natural sound of letters".[1]

When Thomas Sheridan's Pronouncing the Spelling Dictionary appeared in 1780, Manson enlarged his own. But as he wished his Complete Pronouncing Dictionary and English Expositer to be sold at the same low price as his previous edition, no printer would oblige and it was never published.[1]

In 1764 Manson did publish Directions to Play the Literary Cards Invented for the Improvement of Children in Learning and Morals From Their Beginning to Learn Their Letters, Till They Become Proficients in Spelling, Reading, Parsing and Arithmetick (Belfast: Printed for the Author, 1764), a commentary on his adaption and didactic use of card games.[33]

In 1770 he also published a more basic primer that was to run into many editions in the 19th century: A new primer. Or, Child's best guide : Containing, the most familiar words of one syllable, ranged in such order as to avoid the jingle of rhyme, which draws off childrens' [sic] attention from the knowledge of the letters to the sound of the words. The method here pursued being found, by experience, to render spelling more easy to the learner, and less troublesome to the teacher than the common one heretofore practiced.: With a variety of reading lessons.[34]

Mechanical invention

Manson took from his father a small farm on the edge of the town which he called Lilliput. There, in addition to a bowling green, he built for his pupils (and, at a small fee, for the townspeople) a "machine by which he could raise persons above every house in town for an amusing prospect" and, on principles proposed in William Emerson's Mechanics (1769),[35] a velocipede or bicycle—the "flying chariot".[36] (Some accounts, perhaps confusing sparse references to the two machines, credit Manson with some form of airship[37][38] or glider)[39] Manson also invented a multiple spinning wheel. Allowing women and girls to spin flax while attending only to their hands, he presented it to the Belfast Charitable Society, the town's poorhouse and hospital.[1][40]

Manson's Legacy

Manson's ideas were carried forward by the hedge-school masters to whom he gave free instruction. In December 1862 an Antrim paper, The Larne Monthly Visitor, described "Manson's dictionary and spelling book" as "still in large demand over the country".[8]

In Belfast Manson's approach, memorialised by Drennan in his Belfast Monthly Magazine,[1] may have influenced the efforts of Drennan's sister, Martha McTier, in pioneering education for poor girls. Elizabeth Hamilton had approved of these, visiting with McTier in 1793.[41]

Drennan was fulsome in his admiration for Manson, describing him as "the best friend of the rising generations of his time".[1] In 1808 he drew plans for a new grammar school and higher-education college, the future Royal Belfast Academical Institution. An expression of his resolve, in the wake of the 1798 rebellion, to "be content to get the substance of reform more slowly" and with "proper preparation of manners or principles,"[42] these reflected something of the spirit of his proscribed Society of United Irishmen. Admission was to be "perfectly unbiased by religious distinctions" and school government was entrusted democratically to boards of subscribers and boards of masters. But is likely that the commitment to rest discipline on "example" rather than on the "manual correction of corporal punishment"[43] owed something to Manson whose portrait was to hang in the new Institution.

The same year the foundation stone was laid for Drennan's Academical Institution, 1810, a "Lancastrian School" was opened in Frederick Street for "the children of the lower classes". However, the rationale that Joseph Lancaster, visiting Belfast, offered for his peer-tutoring method was reduced to a matter of economy. He described a "mechanical system of education" whereby "above one thousand children may be governed by one master only, at an expense reduced to five shillings per annum".[44] Like Manson, Lancaster had rejected corporal punishment but he did not share the older schoolmaster's trust in the power of "amusement": discipline in Lancastrian could be harsh with children brutally restrained and shamed.[45]

The Ulster poet ("rhyming weaver") James Orr is said to have remembered David Manson when, in his Elegy Written in the Ruins of a Country Schoolhouse (1817) he decried those who insisted their children be drilled, as they had been, in "the Catechism, the Youth's Companion and the Holy Word" and who thus denied them "elocution's grace" and "grammar's art".[46]

Manson, who In 1779 had received the freedom of the borough,[15] was accorded on his death in 1792 the honour in Belfast of a torchlit funeral attended by a large crowd drawn from all classes of society. He and his wife had no children.[2][8]

References

- Drennan, William (February 1811). "Biographical Sketches of Distinguished Persons: David Manson". The Belfast Monthly. 6: 126–132. JSTOR 30073837.

- Frogatt, Richard. "The Dictionary of Ulster Biography". www.newulsterbiography.co.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- Gordon, Alexander (1888). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 15. pp. 46–48.

- "University of Glasgow - Schools - School of Critical Studies - Research - Funded Research Projects - Georgian Glasgow - Georgian Glasgow People - Hutcheson". www.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- "Local stories from the age of reason and revolution - Institute of Irish Studies - University of Liverpool". www.liverpool.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- Gilmore, Peter; Parkhill, Trevor; Roulston, William (2018). Exiles of '98: Ulster Presbyterian and the United States (PDF). Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 92–95. ISBN 9781909556621. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Courtney, Roger (2013). Dissenting Voices: Rediscovering the Irish Progressive Presbyterian Tradition. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 92–93. ISBN 9781909556065.

- Marshall, John J. (1908). "David Manson, Schoolmaster in Belfast". Ulster Journal of Archaeology. 14 (2/3): (59–72) 60–61. ISSN 0082-7355. JSTOR 20608645.

- McNeill, Mary (1960). The Life and Times of Mary Ann McCracken, 1770–1866. Dublin: Allen Figgis & Co. pp. 36, 44.

- Byrne, Patricia. "Templeton, John | Dictionary of Irish Biography". www.dib.ie. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- "The Dictionary of Ulster Biography". www.newulsterbiography.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Stewart, A. T. Q. (1995). The Summer Soldiers: The 1798 Rebellion in Antrim and Down. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780856405587.

- Pinkerton, William (1896). Historical Notices of Old Belfast and its Vicinity. Belfast: M Ward and Company. p. 188.

- "Businesswoman, campaigner '" the remarkable Mary Ann McCracken". www.newsletter.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "David Manson". Ulster History Circle. 16 April 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- Marshall (1908), p. 63.

- Grogan, Claire (22 April 2016). Politics and Genre in the Works of Elizabeth Hamilton, 1756–1816. Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-317-07852-4.

- Hamilton, Elizabeth (1837). The Cottagers of Glenburnie: A Tale for the Farmer's Ingle-nook. Stirling, Kenney. pp. 295–296.

- "The Cottagers of Glenburnie, Chapter XVIII. Concerning the Duties of a Schoolmaster". www.electricscotland.com. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- Lucy, Gordon (18 July 2022). "Prolific and versatile Belfast-born writer almost unknown at home. Historian Gordon Lucy on the life and works of Elizabeth Hamilton who died just over 200 years ago this month". News Letter.

- Ashford, Gabrielle M (2012). Childhood: Studies in the History of Children in Eighteenth Century Ireland [doctoral dissertation] (PDF). Dublin: Department of History, St. Patrick's College Drumcondra, Dublin City University. pp. 241, 243.

- Stewart, W. A. C.; McCann, W. P. (1967), "The Eighteenth Century: Experiment and Enlightenment", in Stewart, W. A. C.; McCann, W. P. (eds.), The Educational Innovators 1750–1880, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 14–20, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-00531-4_1, ISBN 978-1-349-00531-4, retrieved 26 April 2021

- Stewart, W. A. C.; McCann, W. P. (1967), "The Eighteenth Century: Experiment and Enlightenment", The Educational Innovators 1750–1880, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 3–52, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-00531-4_1, ISBN 978-1-349-00533-8, retrieved 1 April 2023

- Meaney, Geraldine; O'Dowd, Mary; Whelan, Bernadette (2013). Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 (PDF). Liverpool University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 9781846318924. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- Hamilton (1837), pp. 305-304

- Griffin, Sean (2005). "Teaching for enjoyment: David Manson and his 'play school' of Belfast". Irish Educational Studies. 24 (2–3): 133–143. doi:10.1080/03323310500435398. ISSN 0332-3315. S2CID 145533902.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. p. 46. ISBN 0856402729.

- Kennedy, Catriona A. (2004). 'What can women give but tears' : gender, politics and Irish national identity in the 1790s (phd thesis). University of York. p. 131.

- Hamilton (1837), pp. 307-308

- Manson, David (1762), "The Present State and Practices of the Play-School in Belfast", appendix to A New Pocket Dictionary; of English Expositer, Belfast, Danile Blow

- Meaney, Gerardine; O'Dowd, Mary; Whelan, Bernadette (31 July 2013). Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounters and Exchange, 1714-1960. Oxford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-78138-819-8.

- Meaney, Dowd and Whelan (2013), p. 40 n 110

- Meaney, Geraldine; O'Dowd, Mary; Whelan, Bernadette (2013). Reading the Irish Woman: Studies in Cultural Encounter and Exchange, 1714–1960 (PDF). Liverpool University Press. p. 39. ISBN 9781846318924. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- "Manson, David 1726-1792". WorldCat Identities. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- Emerson, William (1769). Mechanics; Or, the Doctrine of Motion. J. Nourse, in the Strand, bookseller in ordinary to his Majesty.

- Marshall (1908) p. 64

- Lowry, Mary (2009). The Story of Belfast and Its Surroundings [1913]. Appletree Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-84758-147-1.

- "Early Education - Story of Belfast". www.libraryireland.com. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- "The Darker Side of Belfast's History". Issuu. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- Marshall (1908), pp. 67-68.

- O'Dowd, Mary (2016). A History of Women in Ireland, 1500-1800. London: Routledge. p. 222. ISBN 9781317877257. Retrieved 30 October 2020.

- Johnson, Kenneth (2013). Unusual Suspects: Pitt's Reign of Alarm and the Lost Generation of the 1790s. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 9780191631979.

- Fisher, Joseph R.; Robb, John H (1913). Royal Belfast Academical Institution. Centenary Volume 1810-1910. Belfast: M'Caw, Stevenson & Orr. pp. 204–205.

- Bardon, Jonathan (1982). Belfast: An Illustrated History. Belfast: Blackstaff Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0856402729.

- Pen Vogler: "The Poor Child's Friend", History Today, February 2015, pp. 4–5.

- Baraniuk, Carol (6 October 2015). James Orr, Poet and Irish Radical. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-317-31747-0.