DeLancey W. Gill

DeLancey Walker Gill (July 1, 1859 – August 31, 1940) was an American drafter, landscape painter, and photographer known for his paintings of Washington, D.C. and his portrait photography of Native Americans with the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology (BAE). Gill first became noted for his landscape illustrations and watercolors, mainly centered on Washington, although also including views of Native American pueblos. Characterized as precise and exact in his landscapes, Gill captured views of working-class and rural areas of D.C. not commonly depicted in period art.

DeLancey W. Gill | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Gill in 1885 | |

| Born | DeLancey Walker Gill July 1, 1859 Camden, South Carolina, U.S. |

| Died | August 31, 1940 (aged 81) Alexandria, Virginia, U.S. |

| Employers | |

| Spouses | Rose DeLima Draper

(m. 1881; died 1893)Katharine Schley Hemmick

(m. 1905) |

| Children | 8, including Minna P. |

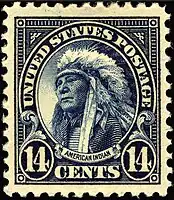

Initially employed as an illustrator and draftsman, Gill was director of the Division of Illustration at the BAE from 1889 to 1932. Although not trained in photography, Gill assumed a role as the BAE's head photographer following the resignation of the Smithsonian's prior photographers. In this duty, he produced thousands of photographs of Native American delegations for the Bureau, including notable figures such as Geronimo and Chief Joseph. As well as in BAE and Smithsonian publications, Gill's photographic work was showcased at the Panama–Pacific Exposition and on a 1923 postage stamp.

Early life and painting career

DeLancey Walker Gill was born in Camden, South Carolina, on July 1, 1859. When he was five, his father was killed in action in service of the Confederate Army. When he was fourteen, his mother and stepfather moved to Fort Laramie in the Wyoming Territory. Gill chose instead to move in with an aunt in Washington, D.C. He briefly worked as a typesetter before finding employment as a draftsman for the Office of the Supervising Architect for the U.S. Treasury, designing ornamental ironwork and tiles. He was noted for his abilities in capturing linear perspective.[1]

While employed as a draftsman, Gill began a series of ink sketches and watercolor paintings, primarily of D.C. landscapes. He especially focused on capturing the rural periphery and villages within the district, still undeveloped in the period.[2] These brought Gill a considerable amount of local acclaim, to the point that Gill received a greater income from art sales than his work with the Treasury.[1]

The art historians Andrew Cosentino and Henry Glassie described Gill's landscape work as having a "razor-sharp clarity of image", citing an account from an anonymous art critic that his watercolors possessed a "certain microscopic exactness and delicacy of detail."[3] Cheryl Miller praised Gill's work as offering a "window on the city's working class – the fishermen, clerks, laundresses, homemakers, and others seldom included in the art of the character".[2]

William Henry Holmes, a fellow watercolor painter and chief of illustration within the United States Geological Survey (USGS), hired Gill as a paleontological draftsman. Holmes came to greatly respect Gill's artistic work, who was tasked to succeed Holmes as chief of illustration in 1889. In this duty he managed the publication of illustrations and photography, reviewing hundreds of thousands of copies of printed illustrations per year. John Wesley Powell, in a dual role as director of the USGS and the BAE, tasked Gill to additionally serve as supervisor of illustration for the Bureau, although without additional pay.[1]

During his initial time with the Bureau in the late 1880s, Gill produced paintings of southwestern pueblos, departing from his prior focus on Washington.[1] These included the Hopi pueblo of Oraibi,[4] the ruins of the Ancestral Puebloan Pueblo Bonito,[5] and the Zuni Pueblo. His painting of Oraibi was based off an earlier photograph by Smithsonian photographer John K. Hillers, but no photographic source is known for the other pueblos within the series. Gill accounted for minutia such as climatic differences in his landscapes, making use of thin washes for his depictions of southwestern locations.[3] While locally regarded as a talented painter, Gill later ceased to paint as duties within government service came to occupy much of his time.[1]

Photography

_of_Samuel_Schanowa_in_Partial_Native_Dress_with_Ornaments_February_1905.jpg.webp)

Gill transferred to the Bureau of American Ethnology in 1898 following Powell's resignation as head of the USGS, leaving him the head of only the BAE. William Dinwiddie had resigned as ethno-photographer for the BAE in 1897; his replacement, Wells M. Sawyer, resigned the following year.[6][1] Despite having no prior training in photography, Gill was appointed to this position following Sawyer's resignation.[1] As photographer for the Bureau, Gill's work consisted of portrait photography of Native American subjects in the hundreds of individuals per year, as well as classifying and cataloging the resulting photographic negatives.[6][1] The total number is unknown but has been estimated to be between 2,000–3,000.[1]

Native delegations to Washington, D.C. increased over the early course of Gill's photographic career, peaking in the winter during congressional sessions.[6] They were generally not paid, although Apache chief Geronimo successfully demanded payment from Gill before shooting. William Henry Holmes, succeeding Powell as Chief of the BAE in 1902, emphasized the "anthropometric elements" of the photographs, placing items with known sizes around subjects in order to allow for facial and cranial measurements to be taken. Ethnographic and historical purposes were also pursued, with subjects often depicted wearing native dress and holding tools or artifacts associated with their tribe.[1]

Prior to 1904, native delegations were photographed at the Downtown offices of the BAE; however, the walk downtown was disliked by the delegations, who preferred to stay in the vicinity of the Smithsonian.[7] The studio was later moved to the upper floor of the Smithsonian's National Museum Building (now the Arts and Industries Building).[1] Members of delegations were spotted and taken to the studio by Andrew John, a Seneca man living in Washington at Beveridge House. Beveridge House served as a popular boardinghouse for native delegations, such that owner Benjamin Beveridge was himself hired to deliver native guests to the BAE following Andrew John's death in 1907. When Beveridge died in 1910, the boardinghouse closed, and photographs stored there were given to Bureau custody.[7]

Gill occasionally took field photography of Native Americans in addition to his studio portraiture. He visited the Pamunkey Reservation in 1899 to photograph tribal members. The following year, he partnered with William John McGee on an expedition to Arizona and New Mexico, photographing members of the Akimel O'odham, Cocopah, Seri, and Tohono Oʼodham. During the 1900s and 1910s, he also accompanied Holmes to document Native American archaeological sites in Maryland, Oklahoma, and Missouri.[1]

Many notable Native American figures were photographed by Gill, including the delegation sent to Washington, D.C. during the second inauguration of Theodore Roosevelt. He described the Nez Perce Chief Joseph, photographed on several occasions, as having "the dignity of a court justice [...] an air of gentleness and quiet reserve."[1] In one 1903 sitting, Gill asked for a totem mark from Joseph. Joseph instead fully signed his name, alongside the year 1900. Joseph ignored protests from Gill regarding the incorrect date, claiming it was exactly how he was taught to sign by a friend.[6][1]

Gill's photography prominently featured in Smithsonian publications during his career, such as Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico and Handbook of North American Indians.[1] His 1905 portrait of Hollow Horn Bear was used as a fourteen-cent postage stamp in 1922.[8] Displays of his prints were shown at the Panama–Pacific International Exposition, Panama–California Exposition, and at various public libraries.[1]

Due to Gill's worsening eyesight, many of his photography duties with the Smithsonian were transferred to A. J. Olmsted in 1926,[1] although he was involved with portrait photography in a limited capacity. During this period he continued to work as illustrations editor for various bureaus of the Smithsonian, including the United States National Museum in addition to the BAE.[1] In October 1931 he photographed Crazy Bull, grandson of Sitting Bull; this would be one of his last photographs taken for the Bureau.[6]

Critique

Gill's early portraits, especially full-body and group photographs, have been characterized as "stiff" and "ill-framed". However his closer-framed portraits, showing just the head and shoulders of the subject, exhibited great artistic efforts and saw significant improvement over the course of his early career. His portraits of Hollow Horn Bear and Wolf Robe have been particularly influential, both as representations of their subjects but of Native Americans generally. He would take great care to edit pieces for prints and publication: his portrait of Wolf Robe was "cropped into a strong design which featured little more than the Indian's striking face and head with the two feathers running off the edge of the paper."[1]

Gill has been criticized for anachronistic and outdated clothing he posed subjects as wearing. In over a dozen cases, subjects from the same delegation were shown with the same clothing and props, including one incident where four Dakota were pictured wearing the same headdress. In one photograph, a Kickapoo subject is shown wearing Blackfoot leggings and an Iowa or Otoe breechclout. However, such errors were to a lesser degree than contemporaries such as Edward S. Curtis.[1]

Personal life

Gill married his first wife, Rose DeLima Draper, on May 25, 1881.[9] They had six children before Rose Gill died in 1893.[1] He married fellow Smithsonian illustrator Mary Irwin Wright on August 19, 1895, having one daughter, suffragist and librarian Minna P. Gill.[10] They divorced in 1903, although they continued business relations for some years afterwards.[1] He later married Katharine Schley Hemmick on January 2, 1905,[11] with whom he had one additional child.[1]

Gill was an active cyclist and a team captain of the Capital Bicycle Club, an early American cyclists' organization, during the 1880s. He was later a member of the Cosmos Club, Society of Washington Artists,[1] and the Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia.[12] He taught classes at the Corcoran School of Art and the Art Students League of Washington.[3]

Following retirement from the Smithsonian, Gill moved from Washington to Alexandria, Virginia.[1] He died on August 31, 1940, fracturing his skull after falling down a staircase at his home.[12]

References

- Glenn, J. R. (1983). "De Lancey W. Gill: Photographer for the Bureau of American Ethnology. History of Photography". History of Photography. 7 (1): 7–22. doi:10.1080/03087298.1983.10442742.

- Miller, Cheryl (1992). "DeLancey Gill's 100-Year-Old Capital City". Washington History. 4 (1): 90–91. JSTOR 40065276 – via JSTOR.

- Cosentino, Andrew J. (1983). The Capital Image: Painters in Washington, 1800–1915. Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 218–219, 260.

- Eldredge, Charles C. (1986). Art in New Mexico, 1900–1945 : paths to Taos and Santa Fe. Abbeville Press.

- "Pueblo Bonito Ruin, Chaco Canyon, New Mexico". Smithsonian American Art Museum.

- Fleming, Paula Richardson; Luskey, Judith (1986). The North American Indians in early photographs. Harper & Row. pp. 178–179. ISBN 9780060155490.

- Viola, Herman J (1981). Diplomats in buckskins: a history of Indian delegations in Washington City. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9780874749441.

- "Hollow Horn Bear". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- "District Brevities". National Republican. May 26, 1881. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- "Social Movements". The Evening Times. August 22, 1895. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- "In the Circle of Society". The Washington Times. January 4, 1905. p. 6.

- "De Lancey Gill, 81, Noted Ethnologist, Dies After Fall". Washington Evening Star. September 1, 1940. p. 8. Archived from the original on November 14, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2023.

External links

Media related to De Lancey W. Gill at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to De Lancey W. Gill at Wikimedia Commons