De regno, ad regem Cypri

De regno, ad regem Cypri (Latin: On kingship, to the king of Cyprus) is a political treatise by Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas written between 1265 and 1266. Dedicated to king Hugh II of Cyprus, the work was left unfinished do to the premature death of the ruler.[1]

Historical context

Unlike other works from Aquinas, De regno defends a strong and authoritarian monarchical rule as necessary and does not favour the creation of a mixed regime. This particular approach has been explained as deriving from the state of social unrest and upheaval caused by a series of internal revolts started in 1233, that caused Cyprus to fall into a state of political unstability.[1][2]

In previous writings Aquinas had proposed a mixed monarchical system in which the king would be aided by an aristocratic class elected by the common population. De regno, however, champions a rather absolutist posture and asks for a strengthening of royal power.[1]

The work was highly influenced by the political doctrines of Albertus Magnus.[3]

Doctrine

.svg.png.webp)

Aquinas limits the scope of the work to monarchical rule, trying to conciliate it with Sacred Scripture, classical philosophy and a Christian view of society.[1][2]

Rulership and common good

The author justifies rulership from a teleological point of view. Aquinas sees eternal happiness and salvation under the guidance of the Catholic Church as the ultimate goal of human life, but recognises the importance of the meeting of basic needs for the achievement of that objective. Considering humans as inherently political beings who gather in societies in order to pursue the common good of satisfying their temporal needs and carrying out a virtuous life, Aquinas concludes the need of having a head who orders society to that goal and does not allow deviations from it.[1] The State is therefore seen as a divine creation for the good of mankind. The legitimacy of political power, however, becomes essentially conditioned to its service to the common good and its obedience to natural law.[2] The existence of the State is not seen as a consequence of original sin but rather as a matter of natural order.[3]

Aquinas analyses different forms of government with the premise that rulership must be oriented to the common good of society and arrives at the conclusion that the rule of a single person is better to lead the community to its goal as it prevents the individual interest of the masses from degrading it and favouring their personal aspirations based on their lower passions. The main function of a ruler, therefore, would be to promote the common good understood as the meeting of human needs and the advancement of Christian virtue. Aquinas still recognises other forms of government as legitimate and potentially good, namely aristocracy and politeia, despite considering them less perfect than monarchy as their natural instability may hinder the adequate search of common good.[1][2]

Depraved forms of government

Aquinas sees humans as beings naturally oriented to the highest good, who are however depraved by original sin that causes deviations on the natural order. A good government, therefore, would be one that is able to direct society to the common good ignoring individual ambitions. The natural disagreements caused by the different passions of human nature must be conciled by a rightful king who orders the country to virtue and prosperity searching for social peace.[1]

Consequently, a bad government would account for one that rules for its own good or for the good of a particular fraction of society. Thomistic common good is seen as universal to all citizens, regardless of the majority's opinion. Aquinas divides perverted governments in three kinds:[1]

- Tyrannies, corruption of monarchies, consisting of the rulership of a single person on his own benefit.

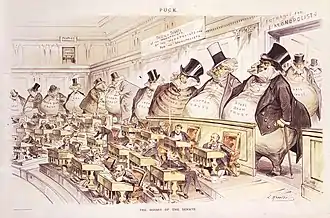

- Oligarchies, corruption of aristocracies, consisting of the rulership of a wealthy elite that oppresses the people to its own benefit.

- Democracy, corruption of politeias, consisting of a self-centered multitude who uses mob rule to oppress those outside of it.

Right of revolution

Seeing tyranny as the worst possible form of government, Aquinas tries to propose ways of preventing it. Rejecting the possibility of a violent uprising, the author defends the establishment of political mechanisms by which the people may use their "public authority" to depose a king who has not "fulfilled his duties".[1] The proposed limits, however, where never stated due to the unfinished character of the work.[2]

Aquinas advises against armed rebellion but states that citizens are not compelled to obey the laws of an illegitimate ruler that go against the highest good.[2] This view has been described as favourable to the "right to resist".[3]

References

- De Lima Júnior, José Urbano (2000). "O pensamento político de Tomás de Aquino no De Regno ad regem Cypri". Dissertatio (in Portuguese). University of Pelotas (12): 49–64.

- Parada Rodríguez, José Luis. (2003). Aproximación a la idea política de Tomás de Aquino. Comparación entre De Regno, de Santo Tomás y El Príncipe, de Nicolás de Maquiavelo.

- Pierpauli, José Paulo (2016). "La filosofía política de Tomás de Aquino: una relectura de la doctrina del De regno desde la obra de Alberto Magno". Lex Humana (in Spanish). Universidad Católica de Petrópolis. 8 (2): 72–96.