William Brodie

William Brodie (28 September 1741 – 1 October 1788), often known by his title of Deacon Brodie, was a Scottish cabinet-maker, Deacon of a trades guild, and Edinburgh city councillor, who maintained a secret life as a housebreaker, partly for the thrill, and partly to fund his gambling.

William Brodie | |

|---|---|

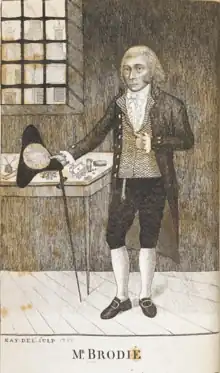

1788 Plate Illustration of William Brodie | |

| Born | 28 September 1741 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 1 October 1788 (aged 47) Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Resting place | St. Cuthbert's Chapel of Ease, Edinburgh |

| Other names | Deacon Brodie |

| Occupation(s) | Locksmith, Councillor |

| Known for | Housebreaking |

| Children | 5 |

| Criminal charge | Robbery |

| Penalty | Hanging |

Life

William Brodie was the son of Francis Brodie, Convenor of Trades in Edinburgh. His father's eminent position allowed William to become the Deacon of Wrights and Masons around 1781.[1]

In 1774, Brodie's mother is listed as the head of household in their Edinburgh home on Brodie's Close on the Lawnmarket. The family (William and his brothers) are listed as "wrights and undertakers" on the Lawnmarket.[2] By 1787 William Brodie is listed alone as a Wright living at Brodie's Close.[3] The house was built towards the foot of the close in 1570, on the south east side of an open court, by Edinburgh magistrate William Little and the close was known as Little's Close until the 18th century.

With 'improvements' being made to Edinburgh, the mansion was demolished around 1835 and is now covered by Victoria Terrace (at a later date, Brodie's workshops and woodyard, which were situated at the lower extremity of the close, made way for the foundations of the Free Library Central Library on George IV Bridge).

By day, Brodie was a respectable tradesman and Deacon (president) of the Incorporation of Wrights, which controlled the craft of cabinetmaking in Edinburgh, and this made him a member of the town council. Part of his work as a cabinetmaker was to install and repair locks and other security mechanisms. He socialised with the gentry of Edinburgh and met the poet Robert Burns and the painter Henry Raeburn. He was a member of the Edinburgh Cape Club[4] and was known by the pseudonym "Sir Llyud".

At night, however, Brodie became a housebreaker and thief. He used his daytime work as a way to gain knowledge about the security mechanisms of his customers and to copy their keys using wax impressions. As the foremost locksmith of the city, Brodie was asked to work in the houses of many of the richest members of Edinburgh society. He used the money he made dishonestly to maintain his second life, which included a gambling habit and five children by two mistresses, who did not know of each other and were unknown in the city.

He reputedly began his criminal career around 1768, when he copied keys to a bank door and stole £800, then enough to maintain a household for several years. In 1786 he recruited a gang of three thieves: John Brown, a thief on the run from a seven-year sentence of transportation; George Smith of Berkshire, a locksmith who ran a grocer's shop in the Cowgate; and Andrew Ainslie, a shoemaker. By 1785 Brodie was spending his evenings gambling at a tavern on Fleshmarket Close owned by a Mr Clark. But his public reputation was high, and in the summer of 1788 he was chosen to sit on a jury in the High Court.[5]

Capture and trial

The case that led to Brodie's downfall began on 5 March 1788, when he organised an armed raid on the excise office in Chessels Court, on the Canongate. He had made a copy of the entry key using putty on an earlier visit and, having made a key, simply unlocked the door. Brodie was accompanied by Smith, Ainslie, and Brown. All were dressed in black, and Brodie and Brown each carried a pair of flintlock pistols. They began around 8pm. Brodie was in high spirits and singing The Beggars Opera. They knew that although the excise office was closed, the night watchman did not come until 10pm. On arrival at Chessels Court, Ainslie stood watch outside.[6]

The plan was disturbed when James Bonar returned to his office unexpectedly at 8.30pm. The gang escaped with only £16. Brodie hurried home, changed into more normal clothes, and went to the house of his mistress Jean Watt, on Libertons Wynd, hoping to create an alibi.[7]

On the same night, Brown approached the authorities to claim a King's Pardon, which had been offered after a previous robbery, and gave up the names of Smith and Ainslie (initially saying nothing of Brodie's involvement). Brown also showed the authorities a cache of duplicate keys hidden under a stone at the base of Salisbury Crags.[8]

Smith and Ainslie were arrested, and the next day Brodie attempted to visit them in prison but was refused. Realising that he had to leave Edinburgh, Brodie travelled southwards and reached Dover in 18 days, closely pursued by George Williamson, a King's Messenger. There Williamson lost the trail. Brodie then backtracked to London, where he stayed until 23 March. He then boarded the Leith ship Endeavour under the name of John Dixon. Endeavor was returning to Edinburgh, but Brodie paid the ship to detour and drop him off in Flushing, the Netherlands, whence he travelled to Ostend. However, on the boat he had given a Mr Geddes several letters to deliver to another mistress, on Cant's Close in Edinburgh. Geddes was suspicious and gave the letters to the authorities in Edinburgh. Williamson resumed his pursuit and found Brodie in Amsterdam, where he was planning to flee to the United States. Brodie was returned to Edinburgh for trial.[9]

The trial of Brodie and Smith started on 27 August 1788. At first there was no hard evidence against Brodie, although the tools of his criminal trade (copied keys, a disguise, and pistols) were found in his house and workshops. But with the evidence provided by Brown and Ainslie, who had been persuaded to turn King's Evidence, along with the self-incriminating lines in the letters Brodie had written while on the run, the jury found Brodie and Smith guilty.

Brodie and Smith were hanged at the Old Tolbooth, on the High Street, on 1 October 1788 before a crowd of 40,000, including Brodie's 10-year-old daughter, Cecil(e). The rope had to be adjusted in length three times as the bell of the adjacent St Giles Cathedral tolled.[10]

According to one tale, Brodie wore a steel collar and silver tube to prevent the hanging from being fatal. It was said that he had bribed the hangman to ignore it and arranged for his body to be removed quickly in the hope that he could later be revived. If so, the plan failed. Brodie was buried in an unmarked grave in the north-east corner of the graveyard at St. Cuthbert's Chapel of Ease, on Chapel Street.[11]

However, rumours that he had been seen in Paris circulated later, giving the story of his scheme to evade death further publicity.

Cultural references

Popular myth holds that Deacon Brodie built the first gallows in Edinburgh and was also its first victim. Of this William Roughead in Classic Crimes states that after research he was sure that although the Deacon may have had some hand in the design, "...it was certainly not of his construction, nor was he the first to benefit by its ingenuity".

Robert Louis Stevenson, whose father owned furniture that had been made by Brodie, wrote a play (with W. E. Henley) entitled Deacon Brodie, or The Double Life, which was unsuccessful. However, Stevenson remained fascinated by the dichotomy between Brodie's respectable façade and his real nature, and this paradox inspired him to write the novella Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which he published in 1886.[12]

Deacon Brodie is commemorated by a pub of that name on Edinburgh's Royal Mile, on the corner of the Lawnmarket and Bank Street which leads down to the Mound; and a close off the Royal Mile, which contained his family residence and workshops, bears the name "Brodie's Close".

A further two pubs carry his name, one in New York City on the south side of the famous west side 46th Street Restaurant Row between Eighth and Ninth avenues, and the other in Ottawa, Canada on the corner of Elgin and Cooper.

The titular character of the novel The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie claims to be descended from Deacon Brodie.[13] His double life serves as a metaphor for her duplicity, as well as her self-imposed demise. The novel has been adapted into a play, film, and television series.

In 1989, Edinburgh rock band Goodbye Mr Mackenzie wrote and recorded a track titled "Here Comes Deacon Brodie", which appeared on the b-side to their hit "The Rattler".

The "Deacon Brodie" episode of the BBC One television drama anthology Screen One starred Billy Connolly as Brodie, aired on 8 March 1997, and was made in Edinburgh.[14]

From 1976 to 1989 Deacon Brodie was a figure in the Chamber of Horrors section of the Edinburgh Wax Museum on the Royal Mile.[15]

References

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Williamson's Edinburgh Directory 1773/4

- Williamson's Edinburgh Street Directory 1787/88

- Deacon Brodie of Edinburgh and Edinburgh Cape Club, Google books

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Grant's Old and New Edinburgh, vol1 chapter 12

- Oslin, Reid (15 March 2001). "Jekyll and Hyde: The Real Story". Boston College Chronicle.

- Spark, Muriel. The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. p. 88.

- Deacon Brodie at IMDb

- Edinburgh Wax Museum Guidebook 1980

Further reading

- Hutchison, David (2014). Deacon Brodie: A Double Life. ISBN 978-1512175172

- Gibson, John Sibbald (1993) [1977]. Deacon Brodie: Father to Jekyll and Hyde. Saltire Society. ISBN 0-904505-24-3

- Bramble, Forbes (1975). The Strange Case of Deacon Brodie. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89292-3

- Roughead, William (1906) The Trial of Deacon Brodie (Notable Scottish Trials series).