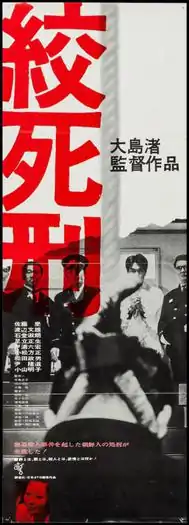

Death by Hanging

Death by Hanging (絞死刑, Kōshikei) is a 1968 Japanese drama film directed by Nagisa Ōshima. It was acclaimed for its innovative Brechtian techniques and complex treatments of guilt and consciousness, justice, and the persecution of ethnic Koreans in Japan.

| Death by Hanging | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Nagisa Ōshima |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Yasuhiro Yoskioka[1] |

| Edited by | Sueko Shiraishi[1] |

| Music by | Hikaru Hayashi[1] |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes[1] |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Plot

A documentary-like opening introduces a death chamber where an execution is about to take place. Inexplicably, the man to be executed, an ethnic Korean known only as R, survives hanging but loses his memory. The officials who witness the hanging debate how to proceed, as the law could be interpreted as forbidding execution of an individual who does not recognize their crime and its punishment. They decide that they must persuade R to accept guilt by reminding him of his crimes – at this point the film moves into a highly theatricalized film-within-a-film structure.

In scenes of absurd and perverse humor, the officials recreate R's first crime, the rape of a young woman. This failing, they attempt to recreate his childhood by way of performing crude racist stereotypes of Koreans held by some Japanese. Exasperated, they resort to visiting the scene of R's other crime at an abandoned high school, but in an overzealous moment of reenactment, an official murders a girl. Back in the death chamber, a woman claiming to be R's "sister" appears one by one to the officials. She tries to convince R that his crimes are justified by Korean nationalism against a Japanese enemy, but after failing to win him over, is herself hanged. At a drinking party to celebrate her hanging, the officials reveal their guilt-ridden, violent pasts, oblivious to R and his "sister" lying on the floor amongst them, themselves exploring R's psyche. The prosecutor invites R to leave a free man, but when he opens the door, he is driven back by an intense burst of light from outside, symbolizing the fact that as a Korean he will never be accepted by Japanese society. Finally, R admits to the crimes, but proclaims himself innocent – stating that if the officers execute him, then they are murderers as well. In his second hanging, R's body disappears, leaving an empty noose hanging beneath the gallows.[2]

Cast

- Do-yun Yu as R

- Kei Satō

- Fumio Watanabe

- Rokko Toura

- Masao Adachi

- Komatsu Hōsei

- Masao Matsuda

- Akiko Koyama

- Nagisa Ōshima as narrator

Production

The character R in Death by Hanging was based on Ri Chin'u, an ethnic Korean who in 1958 murdered two Japanese school girls. A precocious, talented young man, he not only confessed to his crimes, but wrote about them in great detail; his writings, collected as Crime, Death, and Love became nearly as famous as his crimes and persona. Much of his book consisted of correspondence with Bok Junan, a Korean journalist sympathetic to the communist North.[3] The "sister" character was developed from this relationship, indicating the journalist's Korean nationalist interpretation of Ri's life and experiences. Much of R and the "sister's" dialogue is taken from this correspondence. Ōshima held Ri Chin'u in high regard, despite his crimes. Claiming him to be "the most intelligent and sensitive youth produced by postwar Japan", Ōshima thought his prose "ought to be included in high school textbooks". Ōshima first wrote a script about him in 1963, but this was not the version that eventually was filmed.[4] Prior to 1968, the idea was conceptually reworked, with Ri Chin'u negated as the hero and replaced by R, a Korean subject more open to experimental treatment and analysis. The resulting film is just as much concerned with the domestic repression of Koreans in Japan as with the death penalty, but remains cinematically important because of its theoretical and conceptual innovations.[5]

Themes

Guilt and consciousness

For all its dark absurdity, Death by Hanging addresses a number of themes – guilt and consciousness, and also race and discrimination (all within a greater context of state violence) – with great gravity. The guiding juxtaposition is of the criminal consciousness with the state's license to commit violence without guilt. If the state has internalized in its formation communal norms of "guilt" and "justice", thereby wielding violence legitimately (even if – in this case – wrapped in a context of ethnic bigotry), it must still prove guilt to transgressors, in this case, the character R. Guilt is culturally learned, but R presents the difficulty of not being aware of guilt or acknowledgement of violating social boundaries in his crimes; he likewise remains unaware of his own ethnicity and cannot comprehend the link (as it is presented to him) between his ethnicity and his alleged criminality. Both the assorted officials (legal, scientific, and metaphysic representatives) and his "sister" (representative of nationalism) attempt, but fail to recreate R's consciousness. In fact, their own violent actions (simulated rape, murder, recollection of war crimes) and ignorance accentuate the contradiction of violence and guilt – the state that has been sanctioned to kill is constituted by people just as guilty and worthy of punishment as R, the criminal. The implications extend far beyond a mere commentary on the death penalty, but pose an open-ended series of questions about the relationship between the individual and the state, between violence and guilt (or an understood concept of guilt), and between ethnic discrimination and the various products of discrimination: as Koreans were discriminated against and denied legitimacy by Japan, so R denies Japanese state authority. His body's refusal to die becomes an act of resistance against the state and its delineation of justified and unjustified violence.[6] This interpretation resonates with Ōshima's long-standing concern with the plight of the Korean minority, and with the painful history of the Japanese occupation of Korea and war-time atrocities.

A Brechtian theater of the absurd

Despite its documentary style, from the start, as voiceover and image give contradictory information, it is clear that Death by Hanging is not a presentation of "reality". This distancing is compounded by the seven intertitles that give an indication of the action about to occur (or in a psychoanalytic interpretation, displacing R as a defined subject). These techniques have established the film as Ōshima's most Brechtian. Other ideas borrowed from Brecht include dark humor, the theme of justice, and an exploration of open-ended, unresolved contradictions. That a death chamber serves as this unlikely theater of the absurd underscores the film's dominant ironic tone. Rich in symbolism and visual allusions, Ōshima's mise en scène contains a number of subtle, masterful touches, such as the newspapered walls in the reconstruction of R's youth referencing the intense media scrutiny of Ri Chin'u. Another theatrical element observed by Maureen Turim is the important role of dialogue: "much of the humor and irony is a matter of verbal repartee, presented in exquisite timing and visual framing."[5]

Release

Death by Hanging was released theatrically in Japan on March 9, 1968, where it was distributed by Toho.[1] This was the first Toho release in VistaVision size format.[1] The film was released in the United States theatrically by New Yorker Films with English subtitles on December 8, 1971.[1]

Reception

In Japan, the film won the Kinema Junpo Award for Best Screenplay.[1]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times found the film provocative and entertaining while it focused on capital punishment, but felt it reached a point of total confusion as it became more Godardian or Brechtian. He also called Ōshima's directing "hugely concerned and committed to the sort of cinema that plays an active role in its society".[7] Donald Richie of the Japan Times felt that halfway through the film, when R's sister appears, the film's statement is "clear, direct, double-edged, and brilliantly delivered", but afterward it "unravels, getting more and more woolly-headed while the words come thicker and longer and faster". However, he still felt that at the end, the film raised important questions.[8]

References

- Galbraith IV 2008, p. 247.

- Cameron, Ian. "Nagisa Oshima." In Second Wave England: November Books, 1970. pp. 70–80.

- Turim 1998

- Oshima, Nagisa. "About Death By Hanging". pp. 166–169 in Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Ōshima, 1956-1978, ed. Annette Michelson. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1992.

- Turim 1998, pp. 61–81

- Standish, Isolde. A New History of Japanese Cinema New York: Continuum, 2005. pp. 244–250.

- Canby, Vincent (15 February 1974). "Death By Hanging (1968)". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Richie, Donald (28 January 1968). "Donald Richie on 'Koshikei (Death by Hanging)'". The Japan Times. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Turim, Maureen Cheryn (1998). The Films of Oshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast. Berkeley: University of California. ISBN 978-0520206663.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-1461673743. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

External links

- Death by Hanging at IMDb

- Death by Hanging at the Japanese Movie Database (in Japanese)

- Death by Hanging at AllMovie

- Death by Hanging: Hanging by a Thread an essay by Howard Hampton at the Criterion Collection

- Death by Hanging at Rotten Tomatoes