Death Game

Death Game (also known as The Seducers) is a 1977 American psychological thriller film directed by Peter S. Traynor, and starring Sondra Locke, Seymour Cassel, and Colleen Camp. The film follows an affluent San Francisco businessman who finds himself at the mercy of two violent, deranged women whom he unwittingly allows into his home during a rainstorm.

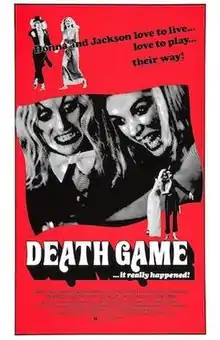

| Death Game | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter S. Traynor |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | David Worth |

| Edited by | David Worth |

| Music by | Jimmie Haskell |

| Color process | Metrocolor |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $150,000[1][2] |

Traynor, a former California real-estate financier, entered a career in filmmaking as a producer in the early 1970s, funding his projects through local investors. He purchased the script for Death Game to serve as his directorial debut. The film was shot primarily inside a large Los Angeles home with a small budget in approximately two weeks during 1974 with a projected release the following summer. Production was allegedly plagued with on-set disputes among the first-time director and the cast, and eventually halted due to a federal investigation into Traynor's financing methods. The theatrical release of Death Game was delayed nearly two years.

Critical reception for Death Game has been mixed among critics. While some read into the plot and violence as social commentary, others rejected it as meaningless exploitation. Death Game made unremarkable box office returns during its limited theatrical run, but found a greater audience with its home media releases in the years that followed. The film has been remade twice, including 2015's Knock Knock, directed by Eli Roth and starring Keanu Reeves, Ana de Armas and Lorenza Izzo. Traynor, Locke, and Camp all took part in this film's production.

Plot

In October 1975, George Manning, a successful San Francisco Bay Area businessman, is left home alone on his 40th birthday while his wife Karen tends to a family emergency. A thunderstorm begins that evening and George is greeted at the door by two attractive young women, drenched from the rain. The ladies, who introduce themselves as Jackson and Donna, explain to him that they intended to reach an address for a party on the other side of town when their car broke down. He invites them inside to dry off and make a call for a friend to pick them up.

After the three chat pleasantly for a while, Jackson finds her way to a bathroom sauna. Donna eventually joins her, and George, curious about where they had gone, walks in on them bathing in the hot tub. The happily-married man is then seduced and coerced into sex with the two strangers. The following morning George awakes to find his guests cooking breakfast. Surprised that they had not left the night before, George is given a vague excuse as to why they never departed.

It quickly becomes apparent that the girls have no intention of leaving. They become uncooperative, obnoxious, and defiant of George as they begin rummaging through the house's contents, putting on his wife's clothes, and even vandalizing the property. George, increasingly upset over their unwelcome presence, threatens to call the police. He stops when Jackson claims that the two are underage, and if caught he could face charges of statutory rape, a lengthy prison sentence, and the dissolution of his family life and career. After narrowly avoiding the girls being discovered by a visiting maid, George attempts to contact the authorities once again before Jackson agrees that they will leave on the condition that George drive them.

George drops the two off at a city bus stop on the opposite side of the Golden Gate Bridge and makes the trip home that night, glad the ordeal is seemingly over. However, his relief is short-lived, as Jackson and Donna ambush him inside his home and knock him unconscious. The duo ties George up with bedsheets and subject him to physical and emotional abuse while continuing to trash the inside of the house, and painting their faces with his wife's makeup. Their sadistic and often bizarre actions escalate as the night goes on.

After George cries for help to a grocery delivery man, the girls usher the unfortunate courier into the living room, bludgeon him, and drown him in a fish tank. George's few struggles to escape fail. George tries to reason with his captors. At one point Jackson reveals to him that her unhinged behavior is due to her own father having sex with her. The girls hold a mock trial amongst themselves to determine if George should face punishment for the supposed sexual crimes he committed the previous evening.

At midnight, Jackson, acting as both a witness and judge, announces his guilty verdict and sentences him to death at dawn. When the six o'clock hour rolls around, Donna holds a now-exhausted George down while Jackson proceeds to carry out his execution using a large cleaver. She spares his life at the last moment and the pair finally take off, laughing maniacally. As the women stroll gleefully through the neighborhood, they stumble into the street and—not paying attention to their surroundings—are struck head-on by a speeding van.

Cast

- Sondra Locke as Agatha Jackson

- Seymour Cassel as George Manning

- Colleen Camp as Donna

- Beth Brickell as Karen Manning

- Michael Kalmansohn as Delivery Boy

- Ruth Warshawsky as Mrs. Grossman

Themes

Literary critic John Kenneth Muir found an underlying feminist theme in Death Game stemming from its depiction of male infidelity and suggested immoral father-daughter relations. Muir explained that the film's narrative consistently points to this motif, including the opening sequence featuring the song "Good Old Dad," the female leads constantly calling George "daddy," and Jackson admitting to being a victim of child sexual abuse at the hands of her father.[3] Muir saw the psychotic Jackson and Donna as the story's true protagonists. He further elaborated that the pair dish out a twisted form of justice against the average family man George, who is not only being punished for his own deeds, but is also serving as a surrogate for the society that made them that way.[4] The film's director himself stated that the film "deals with the truth [...] a reflection of today's society," even implying the physical and mental superiority of women over the opposite sex. "Men often do recognize just how vulnerable they are in the hands of a woman," Traynor said, "and that's why a lot of us put them down."[5]

Production

Cast and crew

The script of Death Game was principally written by Anthony d'Oberoff (credited as "Anthony Overman") and Michael Ronald Ross, who met in 1970 while working as copywriters for Capitol Records; Overman would receive a nomination for Best Album Notes in at the 13th Annual Grammy Awards and later pursued an acting career under the name "Anthony Gordon", while Ross would eventually launch Capitol's reissue program. After initially collaborating on a script dealing with a kidnapping at a girls' school, Ross proposed that they write a psychological thriller in the vein of Roman Polanski's Repulsion during Overman's final two weeks at Capitol before being laid off. The primary inspiration for the story was an incident Ross had experienced in 1969, when he brought a hitchhiking hippie named Donna to the Laurel Canyon home that he was subleasing for Harry Nilsson, where she gradually outstayed her welcome and burned "every" spoon in the household for the purpose of cooking drugs; the character's name was subsequently used in the script.[6]

After considering a multitude of working titles, including Little Miss Queen of Darkness and Night Child, the writers elected to name their first draft of the screenplay Freak as a tribute to Tod Browning's film Freaks. To underline the lesbian undertones of the two female characters' relationship, Ross chose to name the more dominant of the two characters "Jackson" after Jackson Browne, while Overman devised the scene in which the character reads the Marquis de Sade novel Justine. In contrast to his portrayal in the film, the male protagonist — originally named "Parker" after the protagonist of various novels by Richard Stark — was portrayed as a loner.[7]

Overman presented the screenplay to actor-turned-producer Don Devlin (also the father of future producer Dean Devlin), who advised the writers to make Parker an "everyman" character. After several rewrites, during which Parker was renamed "George Manning", the script went through several title changes, including Mrs. Manning's Vacation and Mrs. Manning's Holiday, before settling on Mrs. Manning's Weekend, which was the title used during principal photography.[7] After Delvin and Albert S. Ruddy passed on the project to work on The Fortune and The Godfather respectively, Mrs. Manning's Weekend was optioned in 1972 by Bill Duffy, the husband of screenwriter Jo Heims. Having written Clint Eastwood's films Play Misty for Me and Breezy (and associate producing the latter), Heims wrote a new draft of the film, and began developing the project for Eastwood's The Malpaso Company. In Heims' rewrites, the character of Donna fell in love with George; according to Delvin, Eastwood described her take on the story as "more Breezy than Misty". During this time, Eastwood was set to direct the film with Jack Lemmon playing George and Sondra Locke playing Jackson; Locke, who was over 30 but masqueraded about being younger, said she was attracted to the project after being told by her agent about a role for a "bad girl", a part she had not often played.[8][9] The 1944-born actress was almost twice as old as the character, though she had been lying about her age for years and projected a younger woman's personality in public.[lower-alpha 1]

Following the commercial failure of Breezy, Overman and Ross decided to rewrite Mrs. Manning's Weekend, as Nigg, with the George Manning character being renamed Parker and written as an African-American. The writers hoped to pitch Nigg as a vehicle for Richard Pryor, with whom Overman was personally connected through his wife, singer Niggy Joyce d'Oberoff, once Malpaso's option on the script ran out, but Duffy instead sold the option to Centuar Films, led by Peter S. Traynor, a California real-estate magnate and former life insurance salesman who had entered the motion picture industry as a producer only a few years earlier.[13][14] As with Traynor's real-estate developments, Death Game and his two previous movies, Steel Arena and Truck Stop Women, were funded largely using limited partnerships with California physicians as investors. Death Game was one of several Traynor movies in simultaneous production alongside the features Bogard, The Ultimate Thrill, and Dr. Shagetz.[15] Traynor also served as a producer of Death Game with Larry Spiegel.[16] [17]

Death Game was one of the earliest film roles for Colleen Camp, who had recently left college and appeared mostly in small television roles and commercials up to that point.[18][19][20] Actor Al Lettieri was originally set to play George Manning before the role went to Seymour Cassel, who was, in reality, only nine years older than Locke, while Locke was nine years older than Camp. Comic Marty Allen was also reported to have a cameo as the delivery man early in the movie's development.[21][22]

David Worth served as the film's cinematographer and editor. Jack Fisk was the production designer, while his wife, actress Sissy Spacek, worked as a set dresser.[23][24] A young Bill Paxton also worked as a set decorator on Death Game.[25] The musical score was composed by Jimmie Haskell and features two original vocal themes: "Good Old Dad," with lyrics by Iris Rainer Dart and performed by the Ron Hicklin Singers; and "We're Home," with lyrics by Guy Hemric and performed by Maxine Weldon.[16]

Filming and editing

The production budget for Death Game was $150,000 according to Worth.[1][2] Filming took place in 1974, at which time the movie was known by numerous working titles including "Mrs. Manning's Weekend",[1][26] "Mrs. Manning's Holiday",[27] "Weekend of Terror",[21][22][18] and "Handful of Hours".[15][28][29] Principal photography took between thirteen[1][2] and fifteen[14] days. Traynor chose a large home in Hancock Park, Los Angeles, as a primary filming location, which the crew rented for $1,000 per week.[27] Both Locke and Worth described the filming process for Death Game as extremely tumultuous. Locke claimed the original script for film was much more suspenseful and less exploitive, but that Traynor attempted to interject more comedic elements into the story.[1] Locke criticized the director's lack of leadership, recounting he "didn't have any idea what he needed to be, was, or should be doing." She claimed his direction often consisted of simply telling the two lead actresses to "break something, or eat something".[30][31] This gradually led to Cassel and Locke directing their own performances, as well as that of the less-experienced Camp.[1][32] Tensions on set were high between Traynor and Cassel, as the actor constantly threatened to leave the production. After one scene involving the two female antagonists dumping large amounts of food on his character, Cassel was allegedly so angry he nearly hit the director.[1] He also reportedly refused to loop his character's dialogue once filming wrapped, leaving Worth to dub the voice of George Manning in post-production.[1][31]

After the film's first director of photography was fired, Worth was brought on board as a replacement. Though initially reluctant due to the seemingly chaotic production, Worth took the job after learning that the cast included Locke and Cassel, both of whom had been nominated for an Academy Award for previous works.[1] Worth shot most scenes in anamorphic widescreen[33] using a 35 mm Panavison Panaflex handheld camera.[1][34] Due to a limited budget and tight schedule, Worth found it more effective to simply sit down in a nearby chair to shoot close-ups of the actors rather than arduously set up a tripod each time. He also had to underexpose scenes featuring Locke because of her crow’s feet and fair complexion.[1][34] Locke expressed appreciation for Worth's photography of her in Death Game.[1][33][35] During the last days of filming, she suffered a black eye off the set and had to have her injury concealed by giving her character a large amount of makeup in the film's later scenes.[36]

Death Game was originally set for an early summer 1975 release.[15] However, the film was incomplete by this time and was among several studio projects put on hold due to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission investigating Traynor's financing methods.[14][37] After settling with a consent decree several months later, Traynor sought help from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) to finish Death Game. The company granted the director $100,000 and helped secure Levitt-Pickman as the film's distributor. Editing took place over a three-week period, with Traynor and Worth working together some 15 hours per day, seven days a week to completion.[14]

Release

Box office

Death Game premiered theatrically at the Northway Shopping Center cinema in Colonie, New York, on April 13, 1977, in what Traynor described as a "test market" release.[5] Thanks to the financial aid from Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and distribution handling by Levitt-Pickman, Death Game was considered by Traynor as "a safe bet for drive-ins and as an urban cult attraction".[15] The film subsequently opened in Fresno, California on June 3, 1977.[38] According to Variety and BoxOffice reports, the film's limited theatrical run from May to October 1977 boasted "poor" to "fair" ticket earnings.[39][40]

Critical response

Critical response to Death Game has been mixed dating back to its original 1977 release. At the time of the film's debut in New York, Doug Delisle of The Times Record recognized the potential for contrasting reactions in moviegoers, with viewers either possibly seeing it as "a relentlessly painful and violent film with no purpose, no reason for being" or as "a statement about man's currently violent place in society" and "the inevitability of fate, the inability of man to isolate himself from a hostile environment." Delisle labeled Death Game as an "antithesis of much of the rest of today's cinematic gore", noting that the film strives to depict pain that is personal rather than physical. "Traynor's violence is not of the slick, exploitative variety," he summarized. "He doesn't show volumes of blood staining the celluloid with potential box office bucks."[5]

Many journalists praised the film's structure and acting. Delisle stated that even with several plot holes, the film is "engrossing" and "extremely well-made" despite its modest budget, and that all three lead actors present "splendidly vivid and realistic portrayals" of their characters.[5] Muir echoed this, proclaiming Death Game as "a riveting, sexual psycho-thriller, and well-directed and acted", finding it to have "the same discomforting adrenaline surge one feels in The Last House on the Left or Fatal Attraction".[16] BoxOffice found the plot to have a "fascinating quality", whether based on true events or not.[17] Rich Osmond of Cashiers du Cinemart stated that although he found much of the narrative "laughable and inept," he credited the lead actresses for conveying "genuinely creepy" moments in the film's second half.[31] Others responded much more negatively to Death Game. Critic Leonard Maltin denounced the plot entirely, calling it as an "unpleasant (and ultimately ludicrous) film about two maniac lesbians who—for no apparent reason—tease, titillate, and torture a man in his own house."[41] Variety similarly dismissed it as "another grisly try at horror exploitation and, as such, looms as possibly a fast-turn-over item in a situation afflicted with the severest case of product shortage."[26]

Home media

Death Game found somewhat greater prominence on cable television and in video rental stores in the years that followed.[36] It received domestic VHS releases in the US by United Entertainment under the title The Seducers beginning in 1981. The distribution rights then went to VCI Entertainment and the film was re-released on VHS in 1984[42] and on DVD beginning in 2004.[43][44] Finally, distribution was acquired by Grindhouse Releasing around 2010.[45][46] Death Game has been given international distribution, such as a UK release from Brent Walker[47] and an Australian release by Intervision Video.[48] In 2022, the film was re-released on Blu-ray by Grindhouse Releasing in its original, anamorphic widescreen format.[1]

Remakes

Death Game has been remade twice. It was first adapted into the 1980 Spanish film Vicious and Nude (Spanish: Viciosas al Desnudo), directed by Manuel Esteba and starred Jack Taylor, Adriana Vega, and Eva Lyberten. This release's sex scenes and violence are much more explicit than in the 1977 original.[49]

Death Game was remade again as 2015's Knock Knock, directed by Eli Roth and starred Keanu Reeves, Ana de Armas and Lorenza Izzo. Some of the principal cast and crew of the 1977 film participated in the production of Knock Knock. Peter S. Traynor, Larry Spiegel, Sondra Locke, and Colleen Camp were all credited as executive producers. Anthony Overman and Michael Ronald Ross are credited with the story.[50] Camp also has a cameo in Knock Knock.[23]

Notes

References

- White, Mike (January 16, 2016). "Special Report: Death Game / Knock Knock". The Projection Booth (Podcast). Interviews with Larry Spiegel, Sondra Locke, and David Worth. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- Cineycine staff (January 17, 2017). "Entrevista a David Worth" [David Worth Interview] (in Spanish). Cineycine. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Muir 2007, p. 464.

- Muir 2007, pp. 464–465.

- Delisle, George (April 13, 1977). "Death Game has Pluses, Minuses". The Times Record. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

- Szulkin, David (2021). Death Game, Replayed (booklet). Grindhouse Releasing. p. 2. GRD014.

- Szulkin, David (2021). Death Game, Replayed (booklet). Grindhouse Releasing. p. 3. GRD014.

- Szulkin, David (2021). Death Game, Replayed (booklet). Grindhouse Releasing. p. 3-4. GRD014.

- Locke 1997, pp. 128–130.

- Town & County staff (May 10, 1969). "Just Ask". The Free Lance–Star. Vol. 85, no. 111. p. A-7.

- Raymond, Kitty (May 28, 2010). "HAPPY BIRTHDAY for May 28". San Francisco Examiner. p. A27 – via Newspapers.com.

Actress Sondra Locke is 66.

- Stecher, Raquel (March 18, 2022). "Starring Sondra Locke". Turner Classic Movies.

- Szulkin, David (2021). Death Game, Replayed (booklet). Grindhouse Releasing. p. 5. GRD014.

- Cocchi, John (May 16, 1977). "'Game' is Launched by Peter S. Traynor". BoxOffice. Vol. 111, no. 6. p. 8. ISSN 0006-8527.

- BoxOffice staff (January 27, 1975). "Peter Traynor Sets Up Distribution Company". BoxOffice. Vol. 106, no. 16. p. 3. ISSN 0006-8527.

- Muir 2007, p. 463.

- BoxOffice staff (April 25, 1977). "Feature Reviews". BoxOffice. Vol. 111, no. 3. pp. 65–66. ISSN 0006-8527.

- Morning News staff (October 31, 1974). "True Blond". The Morning News. p. 38. ISSN 1042-4121 – via Newspapers.com.

- Erwin, Fran (May 26, 1977). "From Bird Girl at Busch Gardens to movie star, her career takes flight". The Valley News. p. 60. ISSN 0192-7264.

- Hereford Brand staff (April 6, 1975). "On the TV Scene". Hereford Brand. p. 14. OCLC 13695046.

- Anderson, George (October 21, 1974). "Local Angle". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 12. ISSN 1068-624X.

- The Monster Times staff (April 1975). "The Monster Times Teletype". The Monster Times. No. 40. p. 24. OCLC 8549054.

- King, Susan (October 3, 2015). "In 'Knock Knock,' actress Colleen Camp has a cameo—and a producer credit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- Thomas, Bob (May 25, 1977). "Spacek Seeks New Horizons". Nevada Evening Gazette. p. 37. ISSN 0745-1415.

- Sobczynski, Peter (February 26, 2017). "Bill Paxton: 1955–2017". Roger Ebert. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Variety staff (May 1989). "1977: April 27". Variety's Film Reviews: 1975–1977. Vol. 14. New York City: R.R. Bowker. ISBN 978-0-8352-2794-0.

- Kilday, Gregg (February 8, 1975). "He's Doing a Land-Office Business". Los Angeles Times. p. 34 – via Newspapers.com.

- Taylor, Nora E. (March 16, 1975). "Making Movies For Fun and $$$". The Lowell Sun. p. 79 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bladen, Barbara (March 20, 1975). "Filmmaker Thrives On Self-Confidence and High Picture Grosses". The San-Mateo Times. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- Locke 1997, p. 129.

- Osmond 2010, pp. 143–144.

- Locke 1997, pp. 129–130.

- Juniper Stratford, Jennifer (February 27, 2013). "Off Hollywood - David Worth". Vice Media. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- Guarisco, Don (March 6, 2012). "Warrior of the Lost Drive-In: An Interview with David Worth Part 1". Schlockmania. Archived from the original on October 26, 2016. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- McGilligan 2002, p. 318.

- Locke 1997, p. 130.

- Johnson, Sharon (October 17, 1976). "He Leads them to Shelters". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2017.

- "Now Exclusively These Two Theaters: Death Game". Fresno Bee. June 3, 1977. p. 46 – via Newspapers.com.

- BoxOffice staff (May 2, 1977). "Boxoffice Bookguide". BoxOffice. Vol. 111, no. 4. Kansas City, Missouri: BoxOffice Media. p. 69. ISSN 0006-8527.

- BoxOffice staff (October 31, 1977). "Boxoffice Bookguide". BoxOffice. Vol. 112, no. 4. Kansas City, Missouri: BoxOffice Media. p. 65. ISSN 0006-8527.

- Maltin, Leonard (October 29, 1992). Leonard Maltin's Movie and Video Guide 1993. New York City: Plume. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-452-26857-9.

- Billboard staff (November 24, 1984). "New Releases". Billboard. Vol. 96, no. 47. p. 55. ISSN 0006-2510.

- DVD Empire staff (August 5, 2004). "Death Game (VCI)". DVDEmpire.com. Retrieved 2017-09-03.

- VCI staff (May 29, 2007). "Death Game & Murder Rap". VCI Entertainment. Retrieved 2017-09-30.

- Lianne Spiderbaby (January 2011). "The Grindhouse Lives!". Fangoria. No. 299. p. 37. ISSN 0164-2111.

- Ridley, Jim (September 2, 2010). "An Oscar winner goes Grindhouse with Gone with the Pope, the movie the Vatican doesn't want you to see". Nashville Scene. Archived from the original on October 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- H.M. Stationery Office (1979). "Classified". Trade and Industry. ISSN 0006-5323.

- Cinema Papers staff (February 1982). "Film Censorship Listings". Cinema Papers. No. 36. p. 89. ISSN 0311-3639.

- Lázaro Reboll, Antonio; Willis, Andrew (September 4, 2004). Spanish Popular Cinema. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-7190-6282-7.

- Gingold, Michael (October 7, 2015). "Q&A: "KNOCK KNOCK"! Who's There? Director Eli Roth, on Keanu, "Free Pizza" and More". Fangoria. The Brooklyn Company, Inc. Archived from the original on 2017-10-23. Retrieved 2017-09-02.

Sources

- Locke, Sondra (1997). The Good, The Bad & The Very Ugly: A Hollywood Journey. New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 978-0-688-15462-2.

- McGilligan, Patrick (2002). Clint: The Life and Legend. New York City: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-29032-0.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2007). Horror Films of the 1970s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 462–466. ISBN 978-0-7864-3104-5.

- Osmond, Rich (2010). Impossibly Funky: A Cashiers du Cinemart Collection. Albany, Georgia: Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-547-4.

External links

- Death Game at IMDb