Debt deflation

Debt deflation is a theory that recessions and depressions are due to the overall level of debt rising in real value because of deflation, causing people to default on their consumer loans and mortgages. Bank assets fall because of the defaults and because the value of their collateral falls, leading to a surge in bank insolvencies, a reduction in lending and by extension, a reduction in spending.

The theory was developed by Irving Fisher following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression. The debt deflation theory was familiar to John Maynard Keynes prior to Fisher's discussion of it, but he found it lacking in comparison to what would become his theory of liquidity preference.[1] The theory, however, has enjoyed a resurgence of interest since the 1980s, both in mainstream economics and in the heterodox school of post-Keynesian economics, and has subsequently been developed by such post-Keynesian economists as Hyman Minsky[2] and by the neo-classical mainstream economist Ben Bernanke.[3]

Fisher's formulation (1933)

In Fisher's formulation of debt deflation, when the debt bubble bursts the following sequence of events occurs:

Assuming, accordingly, that, at some point in time, a state of over-indebtedness exists, this will tend to lead to liquidation, through the alarm either of debtors or creditors or both. Then we may deduce the following chain of consequences in nine links:

- Debt liquidation leads to distress selling and to

- Contraction of the money supply, as bank loans are paid off, and to a slowing down of velocity of circulation. This contraction of the money supply and its velocity, precipitated by distress selling, causes

- A fall in the level of prices, in other words, a swelling of the dollar. Assuming, as above stated, that this fall of prices is not interfered with by reflation or otherwise, there must be

- A still greater fall in the net worths of business, precipitating bankruptcies and

- A like fall in profits, which in a "capitalistic," that is, a private-profit society, leads the concerns which are running at a loss to make

- A reduction in output, in trade and in employment of labor. These losses, bankruptcies and unemployment, lead to

- pessimism and loss of confidence, which in turn lead to

- Hoarding and slowing down still more the velocity of circulation.

- The above eight changes cause

- Complicated disturbances in the rates of interest, in particular, a fall in the nominal, or money, rates and a rise in the real, or commodity, rates of interest.

— (Fisher 1933)

Rejection of previous assumptions

Prior to his theory of debt deflation, Fisher had subscribed to the then-prevailing, and still mainstream, theory of general equilibrium. In order to apply this to financial markets, which involve transactions across time in the form of debt – receiving money now in exchange for something in future – he made two further assumptions:[4]

- (A) The market must be cleared—and cleared with respect to every interval of time.

- (B) The debts must be paid. (Fisher 1930, p.495)

In view of the Depression, he rejected equilibrium, and noted that in fact debts might not be paid, but instead defaulted on:

It is as absurd to assume that, for any long period of time, the variables in the economic organization, or any part of them, will "stay put," in perfect equilibrium, as to assume that the Atlantic Ocean can ever be without a wave.

— (Fisher 1933, p. 339)

He further rejected the notion that over-confidence alone, rather than the resulting debt, was a significant factor in the Depression:

I fancy that over-confidence seldom does any great harm except when, as, and if, it beguiles its victims into debt.

— (Fisher 1933, p. 339)

In the context of this quote and the development of his theory and the central role it places on debt, it is of note that Fisher was personally ruined due to his having assumed debt due to his over-confidence prior to the crash, by buying stocks on margin.

Other debt deflation theories do not assume that debts must be paid, noting the role that default, bankruptcy, and foreclosure play in modern economies.[5]

Initial mainstream interest

Initially Fisher's work was largely ignored, in favor of the work of Keynes.[6]

The following decades saw occasional mention of deflationary spirals due to debt in the mainstream, notably in The Great Crash, 1929 of John Kenneth Galbraith in 1954, and the credit cycle has occasionally been cited as a leading cause of economic cycles in the post-WWII era, as in (Eckstein & Sinai 1990), but private debt remained absent from mainstream macroeconomic models.

James Tobin cited Fisher as instrumental in his theory of economic instability.

Debt-deflation theory has been studied since the 1930s but was largely ignored by neoclassical economists, and has only recently begun to gain popular interest, although it remains somewhat at the fringe in U.S. media.[7][8][9][10]

Ben Bernanke (1995)

The lack of influence of Fisher's debt-deflation in academic economics is thus described by Ben Bernanke in Bernanke (1995, p. 17):

- Fisher's idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

Building on both the monetary hypothesis of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz as well as the debt deflation hypothesis of Irving Fisher, Bernanke developed an alternative way in which the financial crisis affected output. He builds on Fisher's argument that dramatic declines in the price level and nominal incomes lead to increasing real debt burdens, which in turn leads to debtor insolvency, thus leading to lowered aggregate demand and further decline in the price level, which develops into a debt deflation spiral. According to Bernanke a small decline in the price level simply reallocates wealth from debtors to creditors without doing damage to the economy. But when the deflation is severe, falling asset prices along with debtor bankruptcies lead to a decline in the nominal value of assets on bank balance sheets. Banks will react by tightening their credit conditions. That in turn leads to a credit crunch that does serious harm to the economy. A credit crunch lowers investment and consumption, which leads to declining aggregate demand, which additionally contributes to the deflationary spiral.[11]

Post-Keynesian interpretation

Debt deflation has been studied and developed largely in the post-Keynesian school.

The financial instability hypothesis of Hyman Minsky, developed in the 1980s, complements Fisher's theory in providing an explanation of how credit bubbles form: the financial instability hypothesis explains how bubbles form, while debt deflation explains how they burst and the resulting economic effects. Mathematical models of debt deflation have recently been developed by post-Keynesian economist Steve Keen.

Solutions

Fisher viewed the solution to debt deflation as reflation – returning the price level to the level it was prior to deflation – followed by price stability, which would break the "vicious spiral" of debt deflation. In the absence of reflation, he predicted an end only after "needless and cruel bankruptcy, unemployment, and starvation",[12] followed by "a new boom-depression sequence":[13]

Unless some counteracting cause comes along to prevent the fall in the price level, such a depression as that of 1929-33 (namely when the more the debtors pay the more they owe) tends to continue, going deeper, in a vicious spiral, for many years. There is then no tendency of the boat to stop tipping until it has capsized. Ultimately, of course, but only after almost universal bankruptcy, the indebtedness must cease to grow greater and begin to grow less. Then comes recovery and a tendency for a new boom-depression sequence. This is the so-called "natural" way out of a depression, via needless and cruel bankruptcy, unemployment, and starvation. On the other hand, if the foregoing analysis is correct, it is always economically possible to stop or prevent such a depression simply by reflating the price level up to the average level at which outstanding debts were contracted by existing debtors and assumed by existing creditors, and then maintaining that level unchanged.

Later commentators do not in general believe that reflation is sufficient, and primarily propose two solutions: debt relief – particularly via inflation – and fiscal stimulus.

Following Hyman Minsky, some argue that the debts assumed at the height of the bubble simply cannot be repaid – that they are based on the assumption of rising asset prices, rather than stable asset prices: the so-called "Ponzi units". Such debts cannot be repaid in a stable price environment, much less a deflationary environment, and instead must either be defaulted on, forgiven, or restructured.

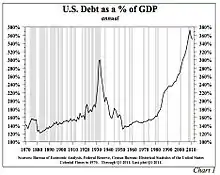

Widespread debt relief either requires government action or individual negotiations between every debtor and creditor, and is thus politically contentious or requires much labor. A categorical method of debt relief is inflation, which reduces the real debt burden, as debts are generally nominally denominated: if wages and prices double, but debts remain the same, the debt level drops in half. The effect of inflation is more pronounced the higher the debt to GDP ratio is: at a 50% ratio, one year of 10% inflation reduces the ratio by approximately to 45%, while at a 300% ratio, one year of 10% inflation reduces the ratio by approximately to 270%. In terms of foreign exchange, particularly of sovereign debt, inflation corresponds to currency devaluation. Inflation results in a wealth transfer from creditors to debtors, since creditors are not repaid as much in real terms as was expected, and on this basis this solution is criticized and politically contentious.

In the Keynesian tradition, some suggest that the fall in aggregate demand caused by falling private debt can be compensated for, at least temporarily, by growth in public debt – "swap private debt for government debt", or more evocatively, a government credit bubble replacing the private credit bubble. Indeed, some argue that this is the mechanism by which Keynesian economics actually works in a depression – "fiscal stimulus" simply meaning growth in government debt, hence boosting aggregate demand. Given the level of government debt growth required, some proponents of debt deflation such as Steve Keen are pessimistic about these Keynesian suggestions.[14]

Given the perceived political difficulties in debt relief and the suggested inefficacy of alternative courses of action, proponents of debt deflation are either pessimistic about solutions, expecting extended, possibly decades-long depressions, or believe that private debt relief (and related public debt relief – de facto sovereign debt repudiation) will result from an extended period of inflation.

Empirical support and modern mainstream interest

Several studies prove that the empirical support for the validity of the debt deflation hypothesis as laid down by Fisher and Bernanke is substantial, especially against the background of the Great Depression. Empirical support for the Bernanke transmission mechanism in the post–World War II economic activity is weaker.[15]

There was a renewal of interest in debt deflation in academia in the 1980s and 1990s,[16] and a further renewal of interest in debt deflation due to the financial crisis of 2007–2010 and the ensuing Great Recession.[6]

In 2008, Deepak Lal wrote, "Bernanke has made sure that the second leg of a Fisherian debt deflation will not occur. But, past and present U.S. authorities have failed to adequately restore the balance sheets of over-leveraged banks, firms, and households."[17] After the financial crisis of 2007-2008, Janet Yellen in her speech acknowledged Minsky's contribution to understanding how credit bubbles emerge, burst and lead to deflationary asset sales.[18] She described how a process of balance sheet deleveraging ensued while consumers cut back on their spending to be able to service their debt. Similarly invoking Minsky, in 2011 Charles J. Whalen wrote, "the global economy has recently experienced a classic Minsky crisis - one with intertwined cyclical and institutional (structural) dimensions."[19]

Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart's works published since 2009[20] have addressed the causes of financial collapses both in recent modern times and throughout history, with a particular focus on the idea of debt overhangs.

References

- Pilkington, Philip (February 24, 2014). "Keynes' Liquidity Preference Trumps Debt Deflation in 1931 and 2008".

- Minsky, Hyman (1992). "The Financial Instability Hypothesis".

- Steve Keen (1995). "Finance and economic breakdown: modelling Minsky’s Financial Instability Hypothesis", Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, Vol. 17, No. 4, 607–635

- Debtwatch No. 42: The economic case against Bernanke, January 24th, 2010, Steve Keen

- "Debt-Reset is Inevitable « Liberty, Love, and Justice for All". Archived from the original on 2013-06-03. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- Out of Keynes's shadow, The Economist, Feb 12th 2009

- Fisher, I. (1933) "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions," Econometrica 1 (4): 337-57

- Grant, J. (2007) "Learn From the Fall of Rome, U.S. Warned," Financial Times (14 August)

- Robert Peston, "UK's debts 'biggest in the world'," BBC (21 November 2011).

- John T. Harvey (Jul 18, 2012). "Why You Should Love Government Deficits". Forbes.

- Randall E. Parker, Reflections on the Great Depression, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, ISBN 9781843765509, p. 14-15

- Compare: "Let us beware of this dangerous theory of equilibrium which is supposed to be automatically established. A certain kind of equilibrium, it is true, is reestablished in the long run, but it is after a frightful amount of suffering.", Simonde de Sismondi, New Principles of Political Economy, vol. 1 (1819), pp. 20–21.

- Irving Fisher on Debt, Deflation, and Depression, Brian Griffin, November 05, 2008, Seeking Alpha

- Can the USA debt-spend its way out?, November 29th, 2008, Steve Keen

- Randall E. Parker, Reflections on the Great Depression, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2003, ISBN 9781843765509, p. 15

- (Bernanke 1995, p. 17)

- Deepak Lal, "The Great Crash of 2008: Causes and Consequences," Cato Journal, 30(2) (2010), p.271-72.

- "A Minsky Meltdown: Lessons for Central Bankers".

- Charles J. Whalen, "Rethinking Economics for a New Era of Financial Regulation: The Political Economy of Hyman Minsky," Chapman Law Review, 15(1) (2011), p. 163.

- "Academic Papers | Kenneth Rogoff".

- Bernanke, Ben (1995), "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach", Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 27 (1): 1–28, doi:10.2307/2077848, JSTOR 2077848

- Fisher, Irving (1933), "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions", Econometrica, 1 (4): 337–357, doi:10.2307/1907327, JSTOR 1907327

- Fisher, Irving (1930). The Theory of Interest as Determined by Impatience to Spend Income and Opportunity to Invest it. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-678-00003-8.

- Eckstein, Otto; Sinai, Allen (1990), "1. The Mechanisms of the Business Cycle in the Postwar Period", in Robert J. Gordon (ed.), The American Business Cycle: Continuity and Change, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-30453-3

- Charles Roxburgh; Susan Lund; Tony Wimmer; Eric Amar; Charles Atkins; Ju-Hon Kwek; Richard Dobbs; James Manyika (January 2010), Debt and deleveraging: The global credit bubble and its economic consequences, McKinsey Global Institute