Decanter

A decanter is a vessel that is used to hold the decantation of a liquid (such as wine) which may contain sediment. Decanters,[1] which have a varied shape and design, have been traditionally made from glass or crystal. Their volume is usually equivalent to one standard bottle of wine (0.75 litre).[2]

A carafe, which is also traditionally used for serving alcoholic beverages, is similar in design to a decanter but is not supplied with a stopper.

History

Throughout the history of wine, decanters have played a significant role in the serving of wine. The vessels would be filled with wine from amphoras and brought to the table where they could be more easily handled by a single servant.

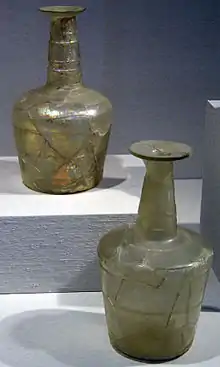

The Ancient Romans pioneered the use of glass as a material. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, glass production became scarce causing the majority of decanters to be made of bronze, silver, gold, or earthenware. The Venetians reintroduced glass decanters during the Renaissance period and pioneered the style of a long slender neck that opens to a wide body, increasing the exposed surface area of the wine, allowing it to react with air.

In the 1730s, British glass makers introduced the stopper to limit exposure to air. Since then, there has been little change to the basic design of the decanter.[2]

Although conceived for wine, other alcoholic beverages, such as cognac or single malt Scotch whisky, are often stored and served in stoppered decanters. Certain cognacs and malt whiskies are sold in decanters such as the 50-year-old single malt Dalmore or the Bowmore Distillery 22 Year Old.

Decanting process

Liquid from another vessel is poured into the decanter in order to separate a small volume of liquid, containing the sediment, from a larger volume of "clear" liquid, which is free of such. In the process, the sediment is left in the original vessel, and the clear liquid is transferred to the decanter. This is analogous to racking, but performed just before serving.

Decanters have been used for serving wines that are laden with sediments in the original bottle. These sediments could be the result of a very old wine or one that was not filtered or clarified during the winemaking process. In most modern winemaking, the need to decant for this purpose has been significantly reduced, because many wines no longer produce a significant amount of sediment as they age.[2]

Decanting cradles

Baskets called decanting cradles, usually made of wicker or metal, are used to decant bottles that have been stored on their side without needing to turn them upright, thereby avoiding stirring up sediment. These are particularly useful in restaurants, for service of a wine ordered during a meal, but less important at home, where a bottle can be stood upright the day before.[3]

More complicated decanting machines also exist to facilitate smoothly pouring, without disturbing sediment.

Aeration

Another reason for decanting wine is to aerate it, or allow it to "breathe". The decanter is meant to mimic the effects of swirling the wine glass to stimulate the oxidation processes which triggers the release of more aromatic compounds. In addition it is thought to benefit the wine by smoothing some of the harsher aspects of the wine (like tannins or potential wine faults like mercaptans).

Many wine writers, such as author Karen MacNeil in the book The Wine Bible, advocate decanting for the purposes of aeration, especially with very tannic wines like Barolo, Bordeaux, Cabernet Sauvignon, Port, and Rhône wines while noting that decanting could be harmful for more delicate wines like Chianti and Pinot noir.[4]

However, the effectiveness of decanting is a topic of debate, with some wine experts such as oenologist Émile Peynaud claiming that the prolonged exposure to oxygen actually diffuses and dissipates more aroma compounds than it stimulates, in contrast to the effects of the smaller scale exposure and immediate release that swirling the wine in a drinker's glass has.[2]

In addition it has been reported that the process of decanting over a period of a few hours does not have the effect of softening tannins. The softening of tannins occurs during the winemaking and oak aging when tannins go through a process of polymerization that can last days or weeks; decanting merely alters the perception of sulfites and other chemical compounds in the wine through oxidation, which can give some drinkers the sense of softer tannins in the wine.[5]

In line with the view that decanting can dissipate aromas, wine expert Kerin O'Keefe prefers to let the wine evolve slowly and naturally in the bottle, by uncorking it a few hours ahead, a practice suggested by wine producers such as Bartolo Mascarello and Franco Biondi Santi. [6]

Other wine experts, such as writer Jancis Robinson, tout the aesthetic value of using a decanter, especially one with an elegant design and made with clear glass, and believe that for all but the most fragile of wines that there is not much significant damage to the wine by decanting it.[7]

See also

References

- "Decanters". Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- Robinson, Jancis (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (Third ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 223-225. ISBN 0-19-860990-6.

- Asimov, Eric (2012-03-07). "Middle Ground in Decanting". The New York Times.

- MacNeil, K (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 93-95. ISBN 1-56305-434-5.

- "Decanting: Aeration -- friend and enemy of wine". Wine Spectator. November 15, 2003. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- "The Great Debate: To Decant or Not?". Wine Enthusiast. May 21, 2015.

- Robinson, Jancis (2003). Jancis Robinson's Wine Course (Third ed.). Abbeville Press. pp. 20–25. ISBN 0-7892-0883-0.

External links

![]() Media related to Decanters at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Decanters at Wikimedia Commons