Decussation

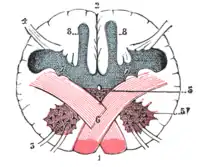

Decussation is used in biological contexts to describe a crossing (due to the shape of the Roman numeral for ten, an uppercase 'X' (decussis), from Latin decem 'ten', and as 'as'). In Latin anatomical terms, the form decussatio is used, e.g. decussatio pyramidum.

Similarly, the anatomical term chiasma is named after the Greek uppercase 'Χ' (chi). Whereas a decussation refers to a crossing within the central nervous system, various kinds of crossings in the peripheral nervous system are called chiasma.

Examples include:

- In the brain, where nerve fibers obliquely cross from one lateral side of the brain to the other, that is to say they cross at a level other than their origin. See for examples Decussation of pyramids and sensory decussation. In neuroanatomy, the term chiasma is reserved for crossing of- or within nerves such as in the optic chiasm.

- In botanical leaf taxology, the word decussate describes an opposite pattern of leaves which has successive pairs at right angles to each other (i.e. rotated 90 degrees along the stem when viewed from above). In effect, successive pairs of leaves cross each other. Basil is a classic example of a decussate leaf pattern.

Decussate phyllotaxis of Crassula rupestris

Decussate phyllotaxis of Crassula rupestris - In tooth enamel, where bundles of rods cross each other as they travel from the enamel-dentine junction to the outer enamel surface, or near to it.

.jpg.webp)

- In taxonomic description where decussate markings or structures occur, names such as decussatus or decussata or otherwise in part containing "decuss..." are common, especially in the specific epithet.[1]

Evolutionary significance

The origin of the contralateral organization, the optic chiasm and the major decussations on the nervous system of vertebrates has been a long standing puzzle to scientists.[2] The visual map theory of Ramón y Cajal has long been popular[3][4] but has been criticized for its logical inconsistence.[5] More recently, it has been proposed that the decussations are caused by an axial twist by which the anterior head, along with the forebrain, is turned by 180° with respect to the rest of the body.[6][7]

See also

References

- Jaeger, Edmund C. (1959). A source-book of biological names and terms. Springfield, Ill: Thomas. ISBN 0-398-06179-3.

- Vulliemoz, S.; Raineteau, O.; Jabaudon, D. (2005). "Reaching beyond the midline: why are human brains cross wired?". The Lancet Neurology. 4 (2): 87–99. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(05)00990-7. PMID 15664541. S2CID 16367031.

- Ramón y Cajal, Santiago (1898). "Estructura del quiasma óptico y teoría general de los entrecruzamientos de las vías nerviosas. (Structure of the Chiasma opticum and general theory of the crossing of nerve tracks)" [Die Structur des Chiasma opticum nebst einer allgemeine Theorie der Kreuzung der Nervenbahnen (German, 1899, Verlag Joh. A. Barth)]. Rev. Trim. Micrográfica (in Spanish). 3: 15–65.

- Llinás, R.R. (2003). "The contribution of Santiago Ramón y Cajal to functional neuroscience". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 4 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1038/nrn1011. PMID 12511864. S2CID 30442863.

- de Lussanet, M.H.E.; Osse, J.W.M. (2015). "Decussation as an axial twist: A comment on Kinsbourne (2013)" (PDF). Neuropsychology. 29 (5): 713–14. doi:10.1037/neu0000163. PMID 25528610.

- de Lussanet, M.H.E.; Osse, J.W.M. (2012). "An ancestral axial twist explains the contralateral forebain and the optic chiasm in vertebrates". Animal Biology. 62 (2): 193–216. arXiv:1003.1872. doi:10.1163/157075611X617102. S2CID 7399128.

- Kinsbourne, M (Sep 2013). "Somatic twist: a model for the evolution of decussation". Neuropsychology. 27 (5): 511–15. doi:10.1037/a0033662. PMID 24040928.

Further reading

- Why does the nervous system decussate?: Stanford Neuroblog

- Fields, R. Douglas (2023-04-19). "Why the Brain's Connections to the Body Are Crisscrossed". Quanta Magazine.

External links

Media related to Decussation at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Decussation at Wikimedia Commons