Desert pavement

A desert pavement, also called reg (in the western Sahara), serir (eastern Sahara), gibber (in Australia), or saï (central Asia)[1] is a desert surface covered with closely packed, interlocking angular or rounded rock fragments of pebble and cobble size. They typically top alluvial fans.[2] Desert varnish collects on the exposed surface rocks over time.

Geologists debate the mechanics of pavement formation and their age.

Formation

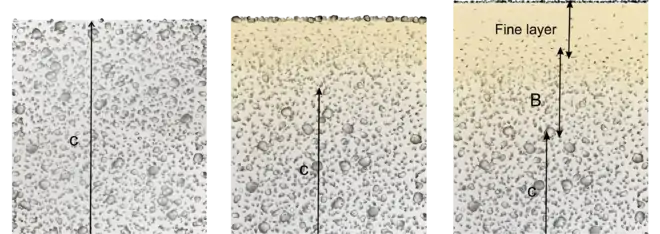

Several theories have been proposed for the formation of desert pavements.[3] A common theory suggests that they form through the gradual removal of sand, dust and other fine-grained material by the wind and intermittent rain, leaving the larger fragments behind. The larger fragments are shaken into place through the forces of rain, running water, wind, gravity, creep, thermal expansion and contraction, wetting and drying, frost heaving, animal traffic, and the Earth's constant microseismic vibrations. The removal of small particles by wind does not continue indefinitely, because once the pavement forms, it acts as a barrier to resist further erosion. The small particles collect underneath the pavement surface, forming a vesicular A soil horizon (designated "Av").

A second theory supposes that desert pavements form from the shrink/swell properties of the clay underneath the pavement; when precipitation is absorbed by clay it causes it to expand, and when it dries it cracks along planes of weakness. Over time, this geomorphic action transports small pebbles to the surface, where they stay through lack of precipitation that would otherwise destroy the pavement by transport of the clasts or excessive vegetative growth.

A newer theory of pavement formation comes from studies of places such as Cima Dome, in the Mojave Desert of California, by Stephen Wells and his coworkers. At Cima Dome, geologically recent lava flows are covered by younger soil layers, with desert pavement on top of them, made of rubble from the same lava. The soil has been built up, not blown away, yet the stones remain on top. There are no stones in the soil, not even gravel.

Researchers can determine how many years a stone has been exposed on the ground. Wells used a method based on cosmogenic helium-3, which forms by cosmic ray bombardment at the ground surface. Helium-3 is retained inside grains of olivine and pyroxene in the lava flows, building up with exposure time. The helium-3 dates show that the lava stones in the desert pavement at Cima Dome have all been at the surface the same amount of time as the solid lava flows right next to them. He wrote in a July 1995 article in Geology, that he concluded, "stone pavements are born at the surface."[4] While the stones remain on the surface due to heave, deposition of windblown dust must build up the soil beneath that pavement.

For the geologist, this discovery means that some desert pavements preserve a long history of dust deposition beneath them. The dust is a record of ancient climate, just as it is on the deep sea floor and in the world's ice caps.

Desert pavement surfaces are often coated with desert varnish, a dark brown, sometimes shiny coating that contains clay minerals. In the USA a famous example can be found on Newspaper Rock in southeastern Utah. Desert varnish is a thin coating (patina) of clays, iron, and manganese on the surface of sun-baked boulders. Micro-organisms may also play a role in their formation. Desert varnish is also prevalent in the Mojave desert and Great Basin geomorphic province.[5]

Local names

.JPG.webp)

Stony deserts may be known by different names according to the region. Examples include:

Gibbers: Covering extensive areas in Australia such as parts of the Tirari-Sturt stony desert ecoregion are desert pavements called Gibber Plains after the pebbles or gibbers.[6] Gibber is also used to describe ecological communities, such as Gibber Chenopod Shrublands or Gibber Transition Shrublands.

In North Africa, a vast stony desert plain is known as reg. This is in contrast with erg, which refers to a sandy desert area.[7]

See also

- Aeolian processes – Processes due to wind activity

- Desert varnish – Orange-to-black rock coating in arid environments

- Eduction (geology), a mechanism of surface rock formation

- Erg – Broad area of desert covered with wind-swept sand

- Hamada – desert landscape with mostly rock instead of sand

- Saltation (geology) – Particle transport by fluids

- Ventifact – Rock that has been eroded by wind-driven sand or ice crystals

Notes

- "Hamada, Reg, Serir, Gibber, Saï". Springer Reference. 2013. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- Sharp, Robert (1997). Geology Underfoot: In Death Valley and Owens Valley. Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 119–130. ISBN 9780878423620.

- McFadden, L.D., Wells, S.G. and Jercinovich, M.J. 1987. "Influences of aeolian and pedogenic processes on the origin and evolution of desert pavements", Geology 15(6):504-508.

- Wells S.G.; McFadden L.D.; Poths J.; Olinger C.T. (1995). "Cosmogenic 3He surface-exposure dating of stone pavements: Implications for landscape evolution in deserts" (PDF). Geology. 23 (7): 613–616. Bibcode:1995Geo....23..613W. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0613:CHSEDO>2.3.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Dorn, R. I. and T. M. Oberlander, 1981, "Microbial Origin of Desert Varnish," Science 213:1245-1247

- East, J.J. 1889. "On the geological structures and physical features of Central Australia", Transactions and Proceedings and Report of the Royal Society of South Australia 12:31-53.

- Jean Dresch et al., Géographie des régions arides, Presses universitaires de France, Paris, 1982. ISBN 2-13-037457-3

References

- Al-Qudah, K.A. 2003. The influence of long-term landscape stability on flood hydrology and geomorphic evolution of valley floor in the northeastern Badin of Jordan. Doctoral thesis, University of Nevada, Reno.

- Anderson, K.C. 1999. Processes of vesicular horizon development and desert pavement formation on basalt flows of the Cima Volcanic Field and alluvial fans of the Avawatz Mountains Piedmont, Mojave Desert, California. Doctoral thesis, University of California, Riverside.

- Goudie, A.S. 2008. The history and nature of wind erosion in deserts. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 36:97-119.

- Grotzinger, et al. 2007. Understanding Earth, fifth edition. Freeman and Company. 458–460.

- Haff, P.K. and Werner, B.T. 1996. Dynamical processes on desert pavements and the healing of surficial disturbance. Quaternary Research 45(1):38-46.

- Meadows, D.G., Young, M.H. and McDonald, E.V. 2006. Estimating the fine soil fraction of desert pavements using ground penetrating radar. Vadose Zone Journal 5(2):720-730.

- Qu Jianjun, Huang Ning, Dong Guangrong and Zhang Weimin. 2001. The role and significance of the Gobi desert pavement in controlling sand movement on the cliff top near the Dunhuang Magao Grottoes. Journal of Arid Environments 48(3):357-371.

- Rieman, H.M. 1979. Deflation armor (desert pavement). The Lapidary Journal 33(7):1648-1650.

- Williams, S.H. and Zimbelman, J.R. 1994. Desert pavement evolution: An example of the role of sheetflood. The Journal of Geology 102(2):243-248.