Deir el-Medina

Deir el-Medina (Egyptian Arabic: دير المدينة), or Dayr al-Madīnah, is an ancient Egyptian workmen's village which was home to the artisans who worked on the tombs in the Valley of the Kings during the 18th to 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (ca. 1550–1080 BCE)[1] The settlement's ancient name was Set maat ("Place of Truth"), and the workmen who lived there were called "Servants in the Place of Truth".[2] During the Christian era, the temple of Hathor was converted into a Monastery of Saint Isidorus the Martyr (Coptic: ⲡⲧⲟⲡⲟⲥ ⲙ̄ⲫⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲡⲁ ⲓⲥⲓⲇⲱⲣⲟⲥ ⲡⲙⲁⲣⲧⲉⲣⲟⲥ)[3] from which the Egyptian Arabic name Deir el-Medina ("Monastery of the City") is derived.[4]

Coptic: ⲡⲧⲟⲡⲟⲥ ⲙ̄ⲫⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲡⲁ ⲓⲥⲓⲇⲱⲣⲟⲥ ⲡⲙⲁⲣⲧⲉⲣⲟⲥ | |

Ruins of Deir el-Medina | |

Location within Egypt | |

| Location | Luxor |

|---|---|

| Region | Upper Egypt |

| Coordinates | 25°43′44″N 32°36′05″E |

| Part of | Theban necropolis |

| History | |

| Builder | Thutmose I |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Ernesto Schiaparelli (1905–09) Bernard Bruyère (1922–51) |

| Criteria | i, iii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 |

| Part of | Ancient Thebes with its Necropolis |

| Reference no. | 87 |

| Region | Egypt |

At the time when the world's press was concentrating on Howard Carter's discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922, a team led by Bernard Bruyère began to excavate the site.[5] This work has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.[6]

The site is located on the west bank of the Nile, across the river from modern-day Luxor.[7] The village is laid out in a small natural amphitheatre, within easy walking distance of the Valley of the Kings to the north, funerary temples to the east and south-east, with the Valley of the Queens to the west.[8] The village may have been built apart from the wider population in order to preserve secrecy in view of sensitive nature of the work carried out in the tombs.[9] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[10]

Excavation history

.jpg.webp)

A significant find of papyri was made in the 1840s in the vicinity of the village and many objects were also found during the course of the 19th century. The archaeological site was first seriously excavated by Ernesto Schiaparelli between 1905–1909 which uncovered large amounts of ostraca. A French team directed by Bernard Bruyère excavated the entire site, including village, dump and cemetery, between 1922–1951. Unfortunately through lack of control it is now thought that about half of the papyri recovered were removed without the knowledge or authorization of the team director.[11]

Around five thousand ostraca of assorted works of commerce and literature were found in a well close to the village.[12] Jaroslav Černý, who was part of Bruyère's team, went on to study the village for almost fifty years until his death in 1970 and was able to name and describe the lives of many of the inhabitants.[13] The peak overlooking the village was renamed "Mont Cernabru" in recognition of Černý and Bruyère's work on the village.[14]

Village

The first datable remains of the village belong to the reign of Thutmose I (c. 1506–1493 BCE) with its final shape being formed during the Ramesside Period.[15] At its peak, the community contained around sixty-eight houses spread over a total area of 5,600 m2 with a narrow road running the length of the village.[16] The main road through the village may have been covered to shelter the villagers from the intense glare and heat of the sun.[5] The size of the habitations varied, with an average floor space of 70 m2, but the same construction methods were used throughout the village. Walls were made of mudbrick, built on top of stone foundations. Mud was applied to the walls, which were then painted white on the external surfaces, while some of the inner surfaces were whitewashed up to a height of around one metre. A wooden front door might have carried the occupants' name.[17] Houses consisted of four to five rooms, comprising an entrance, main room, two smaller rooms, kitchen with cellar and staircase leading to the roof. The full glare of the sun was avoided by situating the windows high up on the walls.[1] The main room contained a mudbrick platform with steps which may have been used as a shrine or a birthing bed.[1] Nearly all houses contained niches for statues and small altars.[18] The tombs built by the community for their own use include small rock-cut chapels and substructures adorned with small pyramids.[19]

Due to its location, the village is not thought to have provided a pleasant environment. The walled village reflects the shape of the narrow valley in which it's situated, with the barren surrounding hillsides reflecting the desert sun and the hill of Gurnet Murai cutting off the north breeze, as well as any view of the verdant river valley.[20] The village was abandoned c. 1110–1080 BCE during the reign of Ramesses XI (whose tomb was the last of the royal tombs built in the Valley of the Kings) due to increasing threats from tomb robbery, Libyan raids and the instability of civil war.[21] The Ptolemids later built a temple to Hathor on the site of an ancient shrine dedicated to her.[22]

Historical texts of Deir el-Medina

The surviving texts record the events of daily life rather than major historical incidents.[23] Personal letters reveal much about the social relations and family life of the villagers. The ancient economy is documented by records of sales transactions that yield information on prices and exchange. Records of prayers and charms illustrate ordinary popular conceptions of the divine, whilst researchers into ancient law and practice find a rich source of information recorded in the texts from the village.[11] Many examples of the most famous works of ancient Egyptian literature have also been discovered.[24] Thousands of papyri and ostraca still await publication.[25]

Village life

The settlement was home to a mixed population of Egyptians, Nubians and Asiatics who were employed as labourers, (stone-cutters, plasterers, water-carriers), as well as those involved in the administration and decoration of the royal tombs and temples.[26] The artisans and the village were organised into two groups, left and right gangs who worked on opposite sides of the tomb walls similar to a ship's crew, with a foreman for each who supervised the village and its work.[1]

As the main well was thirty minutes walk from the village, carriers worked to keep the village regularly supplied with water. When working on the tombs, the artisans stayed overnight in a camp overlooking the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (c. 1479–1458 BCE) that is still visible today. Surviving records indicate that the workers had cooked meals delivered to them from the village.[5]

Based on analysis of income and prices, the workmen of the village would, in modern terms, be considered middle class. As salaried state employees they were paid in rations at up to three times the rate of a field hand, but unofficial second jobs were also widely practiced.[27] At great festivals such as the heb sed the workmen were issued with extra supplies of food and drink to allow a stylish celebration.[28]

The working week was eight days followed by two days holiday, though the six days off a month could be supplemented frequently due to illness, family reasons and, as recorded by the scribe of the tomb, arguing with wife or having a hangover.[29] Including the days given over to festivals, over one-third of the year was time-off for the villagers during the reign of Merneptah (c. 1213–1203 BCE).[30]

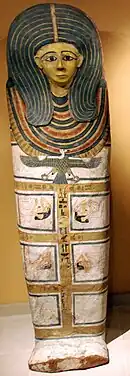

During their days off the workmen could work on their own tombs, and since they were amongst the best craftsmen in Ancient Egypt who excavated and decorated royal tombs, their own tombs are considered to be some of the most beautiful on the west bank.[29]

A large proportion of the community, including women, could at least read and possibly write.[31]

The jobs of the workers would have been considered desirable and prized positions, with the posts being inheritable.[32]

The examples of love songs recovered show how friendship between the sexes was practised, as was social drinking by both men and women.[33] Egyptian marriages amongst commoners were monogamous but little is known about the marriage or wedding arrangements from surviving records.[34] It was not unusual for couples to have six or seven children, with some recorded as having ten.[35]

Separation, divorce and remarriage occurred. Merymaat is recorded as wanting a divorce on account of his mother in-law's behaviour. Female slaves could become surrogate mothers in cases where the wife was infertile and in doing so raise their status and procure their freedom.[36]

The community could move freely in and out of the walled village but for security reasons the only outsiders allowed to enter the site were those with good work-related reasons.[5]

Women and village life

.jpg.webp)

The records from this village provide most of the information we know about how women lived in the New Kingdom era.[37] Women were supplied with servants by the government to assist with the grinding of the grain and laundry tasks.[38] The wives of the workers cared for the children and baked the bread, a prime food source in this society. The vast majority of women who had a particular religious status embedded in their names were married to foremen or scribes and could hold the titles of chantress or singer, with official positions within local shrines or temples, perhaps even within the major temples of Thebes.[37] Under Egyptian law they had property rights. They had title to their own wealth and a third of all marital goods. This would belong solely to the wife in case of divorce or death of the husband. If she died first it would go to her heirs, not to her spouse.[39][40] Brewing of beer was normally supervised by the Mistress of the House, though the workmen considered the monitoring of the activity as a legitimate excuse for taking time off work.[41]

Law and order

The workers and their families were not slaves but free citizens with recourse to the justice system, as required. In principle, any Egyptian could petition the vizier and could demand a trial by his peers.[42] The community had its own court of law made up of a foreman, deputies, craftsmen and a court scribe, and were authorised to deal with all civil and some criminal cases, typically relating to the non-payment of goods or services. The villagers represented themselves and cases could go on for several years, with one dispute involving the chief of police lasting eleven years.[29] The local police, Medjay, were responsible for preserving law and order, as well as controlling access to the tombs in the Valley of the Kings.[29] One of the most famous cases recorded relates to Paneb, the son of an overseer, who was accused of looting royal tombs, adultery and causing unrest in the community. The outcome is not known but surviving records indicate the execution of a head of workmen at this time.[43]

The people of Deir el-Medina often consulted with oracles about many aspects of their lives including justice. Questions could be put in writing or orally before the image of the god when carried by priests upon a litter. A positive response could have been indicated by a downward dip and a negative response by a withdrawal of the litter.[44] When a matter of justice came up that wasn't resolved by a tribunal, the god's statue could be carried to the accused and asked "Is it he who stole my goods?" and, if the statue nodded, the accused would be considered guilty. However, at times, the accused would deny guilt and demand to see another oracle or, in at least one case when that failed, he asked to see a third. When guilt was determined, a judgement would be passed and the accused would have to make reparations and receive punishment. The Egyptians also believed the oracle could bring disease or blindness to people as punishment or miracle cures as rewards.[45]

Medical care

The records and ostraca from Deir el-Medina provide a deeply compelling view into the medical workings of the New Kingdom. As in other Egyptian communities, the workmen and inhabitants of Deir el-Medina received care for their health problems through medical treatment, prayer, and magic.[46] Nevertheless, the records at Deir el-Medina indicate some level of division, as records from the village note both a “physician” who saw patients and prescribed treatments, and a “scorpion charmer” who specialized in magical cures for scorpion bites.[47]

Health texts from Deir el-Medina also differed in their circulation. Magical spells and remedies were widely distributed among the workmen; there are even several cases of spells being sent from one worker to another, with no “trained” intermediary.[48][49] Written medical texts appear to have been much rarer, however, with only a handful of ostraca containing prescriptions, indicating that the trained physician mixed the more complicated remedies himself. There are also several documents that show the writer sending for medical ingredients, but it is unknown whether these were sent according to a physician's prescription, or to fulfill a home remedy.[50]

Popular piety

The excavations of the royal artisans community at Deir el-Medina have revealed much evidence of personal religious practice and cults.[44] State gods were worshipped freely alongside personal gods without any conflict between national and local modes of religious expression.[51]

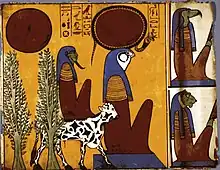

The community had between sixteen and eighteen chapels, with the larger ones dedicated to Hathor, Ptah and Ramesses II. The workmen seem to have honoured Ptah and Resheph, the scribes Thoth and Seshat, as patron deities of their particular activity. Women had particular devotion towards Hathor, Taweret, and Bes in pregnancy, turning to Renenutet and Meretseger for food and safety.[52] Meretseger ("She Who Loves Silence") was perhaps locally at least as important as Osiris, the great god of the dead.[52]

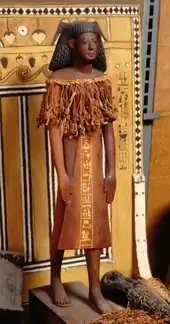

The villagers held Amenhotep I (c. 1526–1506 BCE) and his mother, Queen Ahmose-Nefertari, in high regard over many generations, possibly as divinized patrons of the community.[53] When Amenhotep died he became the centre of a village funerary cult, as "Amenhotep of the Town". When the Queen died, she also was deified and became "Mistress of the Sky" and "Lady of the West".[54] Every year the villagers celebrated the Festival of Amenhotep I, where the elders acted as priests in the ceremonies that paid honour to their own local gods who were not worshipped anywhere else in Egypt.[55]

Prayers were made and dedicated to a particular deity as votive offerings, similar in style to the Penitential Psalms in the Tanakh, which express remorse and thanksgiving for mercy.[56] Steles record sorrow for human error and humbly invoke a god for forgiveness and mercy. In one instance Meretseger is petitioned to bring relief to one in pain. She answer the prayer by bringing "sweet breezes".[57] On another stele, a workman writes, "I was a man who swore falsely by Ptah, Lord of Truth, and he caused me to see darkness by day. Now I will declaim his might to both the ignorant and the knowledgeable.”[5] Amun was considered a special patron of the poor and one who was merciful to the penitent. A stelae records:

[Amun] who comes at the voice of the poor in distress, who gives breath to him who is wretched..You are Amun, the Lord of the silent, who comes at the voice of the poor, when I call to you in my distress You come and rescue me... Though the servant was disposed to do evil, the Lord is disposed to forgive. The Lord of Thebes spends not a whole day in anger, His wrath passes in a moment, none remains. His breath comes back to us in mercy... May your ka be kind, may you forgive, It shall not happen again.[58]

Dream interpretation was very common.[59] A book of dreams was found in Scribe Kenhirkhopeshef's library that was old even in his time. This book was used to interpret various types of dreams. These interpretations lacked precision and similar dreams often had different meanings. In many cases the interpretation was the opposite of what the dream depicted, for example a happy dream often signified sadness, a dream of plenty often signified scarceness etc.

Examples of how the dreams are interpreted include the following:

- If a man sees himself dead this is good; it means a long life in front of him.

- If a man sees himself eating crocodile flesh this is good; it means acting as an official amongst his people. (i.e. becoming a tax collector)

- If a man sees himself with his face in a mirror this is bad; it means a new life.

- If a man sees himself uncovering his own backside this is bad; it means he will be an orphan later.[60]

Also in the temple to Hathor, a few of the craftsmen built stelae in honour of her. One such stela is the stele of Nefersenut, in which he and one of his son's kneeling and giving offerings to her in human form.[61]

Strikes

The royal building service was usually well-run, in view of the importance of the work it carried out. Paying proper wages was a religious duty that formed an intrinsic part of Maat. When this system broke down it indicated problems in the wider state.[62] The coming of the Iron Age and the collapse of the empire led to economic instability, with inflation a notable feature. The high ideals expressed in the code of Maat became strained and this provided the background to workers unrest.[63]

In about the 25th year of the reign of Ramesses III (c. 1170 BCE) the tomb laborers were so exasperated by delays in supplies that they threw down their tools and walked off the job in what may have been the first sit-down strike action in recorded history. They wrote a letter to the vizier complaining about lack of wheat rations. Village leaders attempted to reason with them but they refused to return to work until their grievances were addressed. They responded to the elders with "great oaths". "We are hungry", the crews claimed; "eighteen days have passed this month" and they still had not received their rations. They were forced to buy their own wheat. They told the leaders to send to the pharaoh or vizier to address their concerns. After the authorities had heard their complaints they addressed them and the workers went back to work the next day. Several strikes followed. After one of them, when the strike leader asked the workers to follow him they told him they had had enough and returned to work. This was not the last strike but they soon restored the regular wheat supplies and the strikes came to an end for the remaining years of Ramesses III. However, since the chiefs supported the authorities the workers no longer trusted them and chose their own representatives.[64] Further complaints by the artisans are recorded forty and fifty years after the initial dispute, during the reigns of Ramesses IX and Ramesses X.[65]

Tomb robbing

_but_probably_it_came_from_Deir_el-Medina._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp)

After the reign of Ramses IV (c. 1155–1149 BCE) the conditions of the village became increasingly unsettled. At times there was no work for fear of the enemy. The grain supplies became less dependable and this was followed by more strikes. Gangs of tomb robbers increased, often tunnelling into a tomb through its back so that they wouldn't break the seal and be exposed. A tomb robbery culture developed that included fences and even some officials who accepted bribes. When the Viziers checked the tombs in order to determine whether the seals had been disturbed, they wouldn't report the tomb as having been opened. When they finally did catch tomb robbers, they used limb-twisting tactics to interrogate them and obtain information about where the plunder was and who their accomplices were.

The Abbott Papyrus reports on one occasion, when some officials were looking for a scapegoat, they obtained a confession from a repeat offender after torturing him. However the Vizier was suspicious at how easily the suspect had been produced, so the Vizier asked the suspect to lead them to the tomb that he had robbed. He led them to an unfinished tomb that had never been used and claimed that it was the tomb of Isis. When they retrieved the plunder, they didn't return it to the tombs; instead, they added it to the treasury.[66][67]

Deir el-Medina in fiction

The French Egyptologist and author Christian Jacq has written a tetralogy dealing with Deir el-Medina and its artisans, as well as Egyptian political life at the time.

Deir el-Medina is also mentioned in some of the later books of the Amelia Peabody series by Barbara Mertz (writing as Elizabeth Peters). The village is the setting for some scenes, and late in the series the fictional Egyptologist Radcliffe Emerson is credited with excavations and documentation of the site.

See also

- Servant in the Place of Truth

- Christian Jacq, Egyptologist and author of historical novels on Ancient Egypt, a tetralogy having to do with Deir el-Medina and its artisans.

- Will of Naunakhte, the will of a free woman from Deir el-Medina.

- Jaana Toivari-Viitala, Egyptologist who worked on the role of women at Deir el-Medina

References

- Oakes, p. 110

- Lesko, p. 7

- "Monastery of Saint Isidorus Martyr". An Archaeological Atlas of Coptic Literature.

- Bierbrier, p. 125

- "Pharaoh’s Workers: How the Israelites Lived in Egypt", Leonard and Barbara Lesko, Biblical Archaeological Review, Jan/Feb 1999

- Cambridge Ancient History, p. 380

- Lesko p. 2

- Cambridge Ancient History, p. 379

- "Archaeologica: the world's most significant sites and cultural treasures", Aedeen Cremin, p. 91, Frances Lincoln, 2007, ISBN 0-7112-2822-1

- "Archaeologica: the world's most significant sites and cultural treasures", Aedeen Cremin, p. 384, frances lincolln, 2007, ISBN 0-7112-2822-1

- Lesko, p. 8

- "Archaeologica: the world's most significant sites and cultural treasures", Aedeen Cremin, p. 91, Frances Lincoln, 2007, ISBN 0-7112-2822-1

- "Life of the ancient Egyptians, Eugen Strouhal, Evžen Strouhal, Werner Forman, Editorial Galaxia, p. 187, 1992, ISBN 0-8061-2475-X

- Romer, p. 209

- McDowell pp. 18, 21

- McDowell p. 9

- McDowell pp. 11–12

- Paul Johnson, "The Civilization of Ancient Egypt", p. 131, Book Club Associates (org pub by Weidenfeld & Nicolson), 1978

- Donald B. Redford (Editor), "Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", p. 378, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- Lesko, p. 2

- Bierbrier pp. 119, 120

- McDowell p. 4

- Lesko, p. 2

- Lesko pp. 132, 133

- McDowell p. 8

- Cambridge Ancient History, pp. 379–380

- Lesko, p. 12

- Wilson (1997), pp. 118, 222

- Oakes, p. 111

- Romer, p. 48

- Wilson (1997), p. 72

- Lesko, p. 22

- Lesko p. 34

- Lesko p. 35

- Meskell, p. 74

- Meskell, pp, 95–98

- Lesko p. 28

- Lesko p. 36

- Time Life (1992) pp. 134–142

- Romer

- Wilson (1997) p. 69

- Lesko p. 38

- "Archaeologica: the world's most significant sites and cultural treasures", Aedeen Cremin, p. 91, Frances Lincoln, 2007, ISBN 0-7112-2822-1

- Donald B. Redford (Editor), "Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", p. 80, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- Romer, pp. 100–115, 178

- McDowell, p. 53

- Janssen, Jac. J. "Absence from Work by the Necropolis Workmen of Thebes" Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur bd. 8 (1980): pp. 127–152

- Lesko, p. 68

- McDowell, p. 106

- McDowell, p. 57

- "Religion and Magic in Ancient Egypt", Rosalie David, p. 277, Penguin, 2002, ISBN 0-14-026252-0

- Lesko p. 90

- Lesko, pp. 7, 111

- Tyldesley (1996), p. 62

- Wilson, p. 118

- Donald B. Redford (Editor), "Oxford Guide to Egyptian Mythology", p. 313, Berkley Reference, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- Egyptian Myths, George Hart, p. 46, University of Texas Press, 1990, ISBN 0-292-72076-9

- "Ancient Egyptian Literature", Miriam Lichtheim, pp. 105–106, University of California Press, 1976, ISBN 0-520-03615-8

- John Romer, "Testament", p. 50, Guild Publishing, 1988

- Romer, pp. 68–72

- "Ancient Egypt", Loarna Oakes and Lucia Gahlin, pp. 176–177, Anness Publishing, 2006

- Paul Johnson, "The Civilization of Ancient Egypt", p. 110, Book Club Associates (org pub by Weidenfeld & Nicolson), 1978

- "The Burden of Egypt", John A. Wilson, pp. 278–279, University of Chicago Press, 1951, 4th imp 1963

- Romer, pp. 116–125

- "The Burden of Egypt", John A. Wilson, p. 278, University of Chicago Press, 1951, 4th imp 1963

- Romer, pp. 145–210

- Time Life (1992) pp. 134–142

Bibliography

- Jaroslav Černý, "A Community of Workmen at Thebes in the Ramesside Period", Kairo 1973.

- Leonard H. Lesko, ed. (1994). Pharaoh's Workers: The Villagers of Deir El Medina. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-8143-0.

- Wilson, Hilary (1997). Peoples of the Pharaohs: From Peasant to Courtier. Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-900-3.

- Romer, John (1984). Ancient Lives Daily Life in Egypt of the Pharaohs. Hold, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-000733-X.

- Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs. 1992.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (1996). Hatchespsut: The Female Pharaoh. Viking. ISBN 0-670-85976-1.

- A.G McDowell, “Village Life in Ancient Egypt: Laundry Lists and Love Songs”, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-19-924753-6

- M. L. Bierbrier, "The Tomb-builders of the Pharaohs”, American University in Cairo Press, p. 125, 1989, ISBN 977-424-210-6

- Edited I.E.S Edwards – C.J Gadd – N.G.L Hammond- E.Sollberger, “The Cambridge Ancient History: II Part I , The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c. 1800–13380 B.C”, Cambridge at the University Press, 1973, ISBN 0-521-08230-7

- Lorna Oaks, “The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Pyramids Temples & Tombs of Ancient Egypt", Previously Published as “Sacred Sites of Ancient Egypt”, Southwater, 2006, ISBN 978-1-84476-279-8

- Lynn Meskell, "Private life in New Kingdom Egypt", Princeton University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-691-00448-X

- "Ancient Egypt", Lorna Oakes and Lucia Gahlin, pp. 176–177, Anness Publishing, 2006

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Dayr-al-Madinah

External links

![]() Media related to Deir el-Medina at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Deir el-Medina at Wikimedia Commons