Demodicosis

Demodicosis /ˌdɛmədəˈkoʊsɪs/, also called Demodex folliculitis in humans[1] and demodectic mange (/dɛməˈdɛktɪk/) or red mange in animals, is caused by a sensitivity to and overpopulation of Demodex spp. as the host's immune system is unable to keep the mites under control.

| Demodicosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Demodectic mange, red mange |

| |

| A dog with severe demodectic mange | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, veterinary medicine |

Demodex is a genus of mite in the family Demodecidae. The mites are specific to their hosts, and each mammal species is host to one or two unique species of Demodex mites. Therefore, demodicosis cannot be transferred across species and has no zoonotic potential.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Humans

Demodicosis in humans is usually caused by Demodex folliculorum and may have a rosacea-like appearance.[4][5] Common symptoms include hair loss, itching, and inflammation. An association with pityriasis folliculorum has also been described.[5]

Demodicosis is most often seen in folliculitis (inflammation of the hair follicles of the skin). Depending on the location, it may result in small pustules (pimples) at the base of a hair shaft on inflamed, congested skin. Demodicosis may also cause itching, swelling, and erythema of the eyelid margins. Scales at the base of the eyelashes may develop. Typically, patients complain of eyestrain.

Dogs

Minor cases of demodectic mange usually do not cause much itching but might cause pustules, redness, scaling, leathery skin, hair loss, skin that is warm to the touch, or any combination of these. It most commonly appears first on the face, around the eyes, or at the corners of the mouth, and on the forelimbs and paws. It may be misdiagnosed as a "hot spot" or other skin ailment.

In the more severe form, hair loss can occur in patches all over the body and might be accompanied by crusting, pain, enlarged lymph nodes, and deep skin infections.

Typically, animals become infected through nursing from their mother. The transmission of these mites from mother to pup is normal (which is why the mites are normal inhabitants of the dog's skin), but some individuals are sensitive to the mites due to a cellular immune deficiency, underlying disease, stress, or malnutrition,[6] which can lead to the development of clinical demodectic mange.

Some breeds appear to have an increased risk of mild cases as young dogs, including the Afghan Hound, American Staffordshire Terrier, Boston Terrier, Boxer, Chihuahua, Chow Chow, Shar-Pei, Collie, Dalmatian, Doberman Pinscher, Bulldog, French Bulldog, English Bull Terrier, Miniature Bull Terrier, German Shepherd, Great Dane, Old English Sheepdog, American Pit Bull Terrier, West Highland White Terrier, Rat Terrier, Yorkshire Terrier, Dachshund, and Pug.

Cats

There are two types of demodectic mange in cats. Demodex cati causes follicular mange, similar to that seen in dogs, though it is much less common. Demodex gatoi is a more superficial form of mange, causes an itchy skin condition, and is contagious amongst cats.

Other

Demodectic mange also occurs in other domestic and wild animals, including captive pandas.

Diagnosis

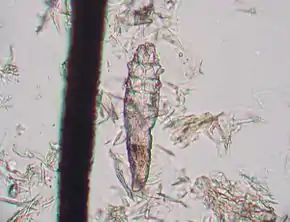

For demodectic mange, properly performed deep skin scrapings generally allow the veterinarian to identify the microscopic mites. Acetate tape impression with squeezing has recently found to be a more sensitive method to identify mites. It was originally thought that because the mite is a normal inhabitant of the dog's skin, the presence of the mites does not conclusively mean the dog has demodicosis. Recent research, however, found that the demodex mite is rarely found on clinically normal dogs, meaning that the presence of any number of mites in a sample is very likely to be significant. In breeds such as the West Highland White Terrier, relatively minor skin irritation which would otherwise be considered allergy should be carefully scraped because of the predilection of these dogs to demodectic mange. Skin scrapings may be used to follow the progress of treatment in demodectic mange.

Alternatively, plasma levels of zinc and copper have been seen to be decreased in dogs with demodicosis.[7] This may be due to inflammation involved in the immune response of demodicosis which can lead to oxidative stress, resulting in dogs with demodicosis to exhibit higher levels of antioxidant productivity.[7] The catalases involved in the antioxidant pathway require the trace minerals zinc and copper. Dogs with demodicosis show a decrease in plasma copper and zinc levels due to the increased demand for antioxidant activity.[7] Therefore, this may be considered as a potential marker for demodicosis.[7]

Treatment

Dogs

Localized demodectic mange is considered a common puppyhood ailment, with roughly 90% of cases resolving on their own with no treatment. Minor, localized cases should be left to resolve on their own to prevent masking of the more severe generalized form. If treatment is deemed necessary, Goodwinol, a rotenone-based insecticide ointment, is often prescribed, but it can be irritating to the skin. Demodectic mange with secondary infection is treated with antibiotics and medicated shampoos.

For more severe generalized cases, Amitraz is a parasiticidal dip that is licensed for use in many countries (the only FDA approved treatment in the USA) for treating canine demodicosis. It is applied weekly or biweekly for several weeks, until no mites can be detected by skin scrapings. Demodectic mange in dogs can also be managed with avermectins, although there are few countries which license these drugs, which are given by mouth daily, for this use. Ivermectin is used most frequently; collie-like herding breeds often do not tolerate this drug due to a defect in the blood–brain barrier, though not all of them have this defect. Other avermectin drugs that can be used include doramectin and milbemycin.

Recent results suggest that the isoxazolines afoxolaner and fluralaner, given orally, are effective in treating dogs with generalized demodicosis.[8][9] Because of the possibility of the immune deficiency being an inherited trait, many veterinarians believe that all puppies with generalized demodex should be spayed or neutered and not reproduce. Females with generalized demodex should be spayed because the stress of the estrus cycle will often bring on a fresh wave of clinical signs.

Cats

Cats with Demodex gatoi must be treated with weekly or bi-weekly sulfurated lime rinses. Demodex cati are treated similarly to canine demodicosis. With veterinary guidance, localized demodectic mange can also be treated with a topical keratolytic and antibacterial agent, followed by a lime sulfur dip or a local application of Rotenone. Ivermectin may also be used. Generalized demodectic mange in cats is more difficult to treat. There are shampoos available that can help to clear dead skin, kill mites and treat bacterial infections. Treatment is in most cases prolonged with multiple applications.[10]

References

- Claude Bachmeyer; Alicia Moreno-Sabater (June 26, 2017). "Demodex folliculitis". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 189 (25): E865. doi:10.1503/cmaj.161323. PMC 5489393. PMID 28652482. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

Demodex folliculorum is a saprophytic parasitic mite of the pilosebaceous follicle and seborrheic glands and is found mainly on the face of adult men.[1,2] The role of Demodex mites in inflammatory skin conditions remains controversial, but is suggested by the efficacy of topical or oral antiparasitic therapy. Demodex folliculorum should be considered whenever a rosacea-like or papulopustular eruption of the face fails to respond to standard therapy for rosacea, and no bacterial pathogens can be implicated.[1] The condition is characterized by itchy pustules, follicular scaling and dryness, conglobata demodicosis with nodulocystic lesions, and blepharitis.[...] Treatment recommendations are supported by case reports and include crotamiton cream, tetracyclines, and topical or systemic metronidazole. Topical and oral ivermectin may be effective in severe cases, although these are not readily available in Canada.

- Izdebska JN, Rolbiecki L. The status of Demodex cornei: description of the species and developmental stages, and data on demodecid mites in the domestic dog Canis lupus familiaris. Med Vet Entomol32:346 – 357, 2018.

- Ran Yuping (2016). "Observation of Fungi, Bacteria, and Parasites in Clinical Skin Samples Using Scanning Electron Microscopy". In Janecek, Milos; Kral, Robert (eds.). Modern Electron Microscopy in Physical and Life Sciences. InTech. doi:10.5772/61850. ISBN 978-953-51-2252-4. S2CID 53472683.

- Baima, B.; Sticherling, M. (2002). "Demodicidosis Revisited". Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 82 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1080/000155502753600795. PMID 12013194.

- Hsu, Chao-Kai; Hsu, Mark Ming-Long; Lee, Julia Yu-Yun (2009). "Demodicosis: A clinicopathological study". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 60 (3): 453–62. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.10.058. PMID 19231642.

- Ectoparasites - Demodex (Mange Mite) Archived 2011-10-07 at the Wayback Machine Companion Animal Parasite Control (March 2013).

- Dimri, Umesh; Ranjan, R.; Kumar, N.; Sharma, M. C.; Swarup, D.; Sharma, B.; Kataria, M. (2008-06-14). "Changes in oxidative stress indices, zinc and copper concentrations in blood in canine demodicosis". Veterinary Parasitology. 154 (1–2): 98–102. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.03.001. ISSN 0304-4017. PMID 18440148.

- Beugnet, Frédéric; Halos, Lénaïg; Larsen, Diane; de Vos, Christa (2016). "Efficacy of oral afoxolaner for the treatment of canine generalised demodicosis". Parasite. 23: 14. doi:10.1051/parasite/2016014. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC 4807374. PMID 27012161.

- Fourie, Josephus; Liebenberg, Julian; Horak, Ivan; Taenzler, Janina; Heckeroth, Anja; Frénais, Regis (2015). "Efficacy of orally administered fluralaner (BravectoTM) or topically applied imidacloprid/moxidectin (Advocate®) against generalized demodicosis in dogs". Parasites & Vectors. 8: 187. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0775-8. PMC 4394402. PMID 25881320.

- Eldredge, Debra M.; Carlson, Delbert G.; Carlson, Liisa D.; Giffin, James M. (2008). Cat Owner's Veterinary Handbook. Howell Book House. p. 144.