Demographics of Istanbul

Throughout most of its history, Istanbul has ranked among the largest cities in the world. By 500 CE, Constantinople had somewhere between 400,000 and 500,000 people, edging out its predecessor, Rome, for world's largest city.[4] Constantinople jostled with other major historical cities, such as Baghdad, Chang'an, Kaifeng and Merv for the position of world's most populous city until the 12th century. It never returned to being the world's largest, but remained Europe's largest city from 1500 to 1750, when it was surpassed by London.[5]

| Demographics of Istanbul | |

|---|---|

Population pyramid of Istanbul in 2022 | |

| Population | 15,519,267 (2019) |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sources:[1] Pre-Republic figures estimated[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Turkish Statistical Institute estimates that the population of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality was 14,377,019 at the end of 2014, hosting 19 percent of the country's population.[6] Then about 97–98% of the inhabitants of the metropolitan municipality were within city limits, up from 89% in 2007[7] and 61% in 1980.[8] 64.9% of the residents live on the European side and 35.1% on the Asian side.[9] While the city ranks as the world's 5th-largest city proper, it drops to the 24th place as an urban area and to the 18th place as a metro area because the city limits are roughly equivalent to the agglomeration. Today, it forms one of the largest urban agglomerations in Europe, alongside Moscow.[lower-alpha 2] The city's annual population growth of 3.45 percent ranks as the highest among the seventy-eight largest metropolises in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The high population growth mirrors an urbanization trend across the country, as the second and third fastest-growing OECD metropolises are the Turkish cities of İzmir and Ankara.[12]

Istanbul experienced especially rapid growth during the second half of the 20th century, with its population increasing tenfold between 1950 and 2000.[13][14] This growth in population comes, in part, from an expansion of city limits—particularly between 1980 and 1985, when the number of Istanbulites nearly doubled.[15] The remarkable growth was, and still is, largely fueled by migrants from eastern Turkey seeking employment and improved living conditions. The number of residents of Istanbul originating from seven northern and eastern provinces is greater than the populations of their entire respective provinces; Sivas and Kastamonu each account for more than half a million residents of Istanbul.[14] Istanbul's foreign population, by comparison, was very small, 42,228 residents in 2007.[16] Only 28 percent of the city's residents are originally from Istanbul.[17] The most densely populated areas tend to lie to the northwest, west, and southwest of the city center, on the European side; the most densely populated district on the Asian side is Üsküdar.[14] As of 2023, Istanbul has Turkey’s biggest foreign migrant population, with 34.5% of foreign nationals in Turkey living there.[18]

Religious groups

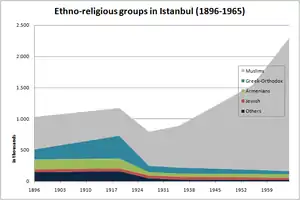

Istanbul has been a cosmopolitan city throughout much of its history, but it has become more homogenized since the end of the Ottoman Empire. The vast majority of people across Turkey, and in Istanbul, are Muslim, and more specifically members of the Sunni branch of Islam. Most Sunni Turks follow the Hanafi school of Islamic thought, while Sunni Kurds tend to follow the Shafi'i school. The largest non-Sunni Muslim group, accounting 10-20% of Turkey's population,[19] are the Alevis; a third of all Alevis in the country live in Istanbul.[17] Mystic movements, like Sufism, were officially banned after the establishment of the Turkish Republic, but they still boast numerous followers.[20] Istanbul is a migrant city. Since the 1950s, Istanbul's population has increased from 1 million to about 10 million residents. Almost 200,000 new immigrants, many of them from Turkey's own villages, continue to arrive each year. As a result, the city is constantly changing and being reshaped to meet the needs of these new arrivals.[21]

The Patriarch of Constantinople has been designated Ecumenical Patriarch since the sixth century, and has come to be regarded as the leader of the world's 300 million Orthodox Christians.[22] Since 1601, the Patriarchate has been based in Istanbul's Church of St. George.[23] Into the 19th century, the Christians of Istanbul tended to be either Greek Orthodox, members of the Armenian Apostolic Church or Catholic Levantines.[24] Today, most of Turkey's remaining Greek, Armenian and Assyrian minorities live in or near Istanbul.[25]

Eldem Edhem, in his entry on "Istanbul" in the Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, wrote that about 50% of the residents of the city were Muslim at the turn of the 20th century.[26]

Ethnic groups

In the late Ottoman period, non-Muslim ethnic minorities in the empire used French as a lingua franca and therefore used French-language newspapers and other media. In addition French businesspeople and vocational workers used French-language media to get in touch with clients in the empire.[27] French-language journalism was initially centred in Smyrna (now Izmir) but by the 1860s it began shifting towards Constantinople.[28] Many newspapers in non-Muslim minority and foreign languages were produced in Galata, with production in daylight hours and distribution at nighttime; Ottoman authorities did not allow production of the Galata-based newspapers at night.[29]

Arabs

The Arabic newspaper Al Jawaib began in Ottoman Constantinople, established by Ahmad Faris al-Shidyaq a.k.a. Ahmed Faris Efendi (1804–1887), after 1860. It published Ottoman laws in Arabic,[30] including the Ottoman Constitution of 1876.[30]

Besides the large communities of both foreign and Turkish Arabs in Istanbul and other large cities, most live in the south and southeast.[31] Most Turkish Arabs in Istanbul are Sunni Muslim, while the remaining consists mainly Arab Christians (Antiochian Greek Christians) and Alawites.[32]

Istanbul, the most populous city in Turkey, hosts the highest number of Syrian refugees, with approximately 550,000 registered people.[33]

Armenians

As of 2015 there are between 50,000 and 70,000 Armenians in Istanbul (0.3-0.5%), down from about 164,000 according to the Ottoman Census of 1913 (14.5%).[34]

Bulgarians

Bulgarian newspapers in the late Ottoman period published in Constantinople were Makedoniya, Napredŭk or Napredǎk ("Progress"), Pravo,[35] and Turtsiya; Johann Strauss, author of "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," described the last one as "probably a Bulgarian version of [the French-language paper] La Turquie."[36]

Greeks

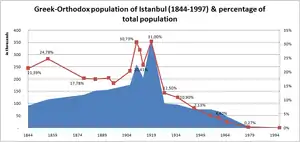

Constantinople had a majority Greek population from the 8th century BCE until the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

After 1453, there remained a group of prominent ethnic Greeks and/or people adopting Greek culture, the Phanariotes, based in the neighbourhood of Phanar, now Fener, in Fatih. About eleven families were a part of the Phanariotes.[37]

The city remained a centre of Greek cultural and political life, and Greeks were a visible presence in the city. According to the Ottoman census of 1893, Greeks made up almost 30% of the city's population, while accounting for 43% of the population in the suburbs.[38] As the city was also home to significant Armenian, Catholic and Jewish minorities, there were more non-Muslims than Muslims in Istanbul, with Muslims making up 44% of the city's population in 1893.[38] The Greek community also dominated the city's economy, owning 50% of the city's total production and distribution capital in 1915.[39] In 1919, of the city's 1,173,670 inhabitants, 364,459 were Greek (31%) and 449,114 were Turk (38%).[40][41]

Because of events during the 20th century—including the Greek genocide, the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey, a 1942 wealth tax, and the 1955 Istanbul riots—the Greek population, originally centered in Fener and Samatya, has decreased substantially.

At the start of the 21st century, Istanbul's Greek population numbered 3,000 (down from 260,000 out of 850,000 according to the Ottoman Census of 1910, and a peak of 350,000 in 1919).[42][43]

Even with these reduced numbers, there remains a Greek-language newspaper, Apoyevmatini, in active circulation.[44]

Jews

The neighbourhood of Balat used to be home to a sizable Sephardi Jewish community, first formed after their expulsion from Spain in 1492.[45] Romaniotes and Ashkenazi Jews resided in Istanbul even before the Sephardim, but their proportion has since dwindled; today, 1 percent of Istanbul's Jews are Ashkenazi.[46][47] In large part due to emigration to Israel, the Jewish population nationwide dropped from 100,000 in 1950 to 18,000 in 2005, with the majority living in either Istanbul or İzmir.[48] As of 2022, the Jewish population in Turkey is around 14,500.[49]

Kurds

The largest ethnic minority in Istanbul is the Kurdish community, originating from eastern and southeastern Turkey. Although the Kurdish presence in the city dates back to the early Ottoman period,[50] the influx of Kurds into the city has accelerated since the beginning of the Kurdish–Turkish conflict with the PKK (i.e. since the late 1970s).[51] About two to four million residents of Istanbul are Kurdish, meaning there are more Kurds in Istanbul than in any other city in the world.[52][53][54][55][56][57]

Levantines

The Levantines, Latin Christians who settled in Galata during the Ottoman period, played a seminal role in shaping the culture and architecture of then-Constantinople during the 19th and early 20th centuries; their population in Istanbul has dwindled, but they remain in the city in small numbers.[58]

Turks

Parallel to the overall demographics of Turkey, Turks are the largest group in Istanbul. Although the presence of Turks in Istanbul goes back to the early Ottoman times, the bulk of this population is composed of recent migrants from the Balkans and Anatolia. [59]

Other ethnicities

There are other significant ethnic minorities as well, the Bosniaks are the main people of an entire district—Bayrampaşa.[60]

From the increase in mutual cooperation between Turkey and several African States like Somalia and Djibouti, several young students and workers have been migrating to Istanbul in search of better education and employment opportunities. c. 2015 the major areas of African settlement are Eminönü and Yenikapi in Fatih, and Kurtulus and Osmanbey in Şişli. The largest groups of Africans that year were from Nigeria and Somalia, with the latter often working in business and the manufacturing of clothing. There are also Cameroonian, Congolese, and Senegalese communities present, with the first group directly involved in the vending of clothing and the last involved in the sale of goods streetside.[61]

As of 2011 about 900 Japanese persons resided in Istanbul; 768 were officially registered with the Japanese Consulate of Istanbul as of October 2010. Of those living in Istanbul, about 450–500 are employees of Japanese companies and their family members, making up around half of the total Japanese population. Others include students of Turkish language and culture, business owners, and Japanese women married to Turkish men. Istanbul has several Japanese restaurants, a Japanese newspaper, and a 32-page Japanese magazine.[62] According to the Istanbul Japanese School, circa 2019 there were about 2,000 Japanese citizens in the Istanbul area, with about 100 of them being children of the ages in which, in Japan, they would be legally required to attend school. At the same period there were about 110 Japanese companies in operation in the city.[63] Istanbul also has a weekend Japanese education programme, The Japanese Saturday School in Istanbul.[64]

After the Romanian revolution, a significant number of Romanian entrepreneurs started investing and establishing business ventures in Turkey, and a certain proportion chose to take up residence there in Istanbul. There are also Romanian migrant workers, as well as students and artists living in the city.[65][66] Some sources claim that there are 14,000 Romanians living in Istanbul.[67] There is also a Romanian Orthodox Church in the city.[68][69]

Russians began migrating to Turkey during the first half of the 1990s. Most had fled the economic problems prevalent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. During this period, many intermarried and assimilated with locals, bringing a rapid increase in mixed marriages. Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, many Russians have fled to Turkey, especially Istanbul, after Vladimir Putin announced a "partial mobilization" of military reservists.[70]

See also

Notes

- Historians disagree—sometimes substantially—on population figures of Istanbul (Constantinople), and other world cities, prior to the 20th century. A follow-up to Chandler & Fox 1974,Chandler 1987, pp. 463–505[2] examines different sources' estimates and chooses the most likely based on historical conditions; it is the source of most population figures between 100 and 1914. The ranges of values between 500 and 1000 are due to Morris 2010, which also does a comprehensive analysis of sources, including Chandler (1987); Morris notes that many of Chandler's estimates during that time seem too large for the city's size, and presents smaller estimates. Chandler disagrees with Turan 2010 on the population of the city in the mid-1920s (with the former suggesting 817,000 in 1925), but Turan, p. 224, is used as the source of population figures between 1924 and 2005. Turan's figures, as well as the 2010 figure,[3] come from the Turkish Statistical Institute. The drastic increase in population between 1980 and 1985 is largely due to an enlargement of the city's limits (see the Administration section). Explanations for population changes in pre-Republic times can be inferred from the History section.

- The United Nations defines an urban agglomeration as "the population contained within the contours of a contiguous territory inhabited at urban density levels without regard to administrative boundaries". The agglomeration "usually incorporates the population in a city or town plus that in the suburban areas lying outside of, but being adjacent to, the city boundaries".[10][11]

Bibliography

- ʻAner, Nadav (2005). Pergola, Sergio Della; Gilboa, Amos; Ṭal, Rami (eds.). The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute Planning Assessment, 2004–2005: The Jewish People Between Thriving and Decline. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House Ltd. ISBN 978-965-229-346-6.

- Athanasopulos, Haralambos (2001). Greece, Turkey, and the Aegean Sea: A Case Study in International Law. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7864-0943-3.

- Brink-Danan, Marcy (2011). Jewish Life in Twenty-First-Century Turkey: The Other Side of Tolerance. New Anthropologies of Europe. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-35690-1.

- Çelik, Zeynep (1993). The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08239-7.

- Chandler, Tertius (1987). Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census. Lewiston, NY: St. David's University Press. ISBN 978-0-88946-207-6.

- Kendall, Elisabeth (2002). "Between Politics and Literature: Journals in Alexandria and Istanbul at the End of the Nineteenth Century". In Fawaz, Leila Tarazi; C. A. Bayly (eds.). Modernity and Culture: From the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. Columbia University Press. pp. 330-. ISBN 9780231114271. - Also credited: Robert Ilbert (collaboration). Old ISBN 0231114273.

- Masters, Bruce Alan; Ágoston, Gábor (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Morris, Ian (October 2010). Social Development (PDF). Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- Rôzen, Mînnā (2002). A History of the Jewish Community in Istanbul: The Formative Years, 1453–1566 (illustrated ed.). Leiden, the Neth.: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-12530-8.

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2005). Levantiner: Lebenswelten und Identitäten einer ethnokonfessionellen Gruppe im osmanischen Reich im "langen 19. Jahrhundert" (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg. ISBN 978-3-486-57713-6.

- Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. pp. 21–51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Turan, Neyran (2010). "Towards an Ecological Urbanism for Istanbul". In Sorensen, André; Okata, Junichiro (eds.). Megacities: Urban Form, Governance, and Sustainability. Library for Sustainable Urban Regeneration. London & New York: Springer. pp. 223–42. ISBN 978-4-431-99266-0.

- Wedel, Heidi (2000). Ibrahim, Ferhad; Gürbey, Gülistan (eds.). The Kurdish Conflict in Turkey. Berlin: LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 181–93. ISBN 978-3-8258-4744-9.

References

- Jan Lahmeyer 2004 Archived 2018-01-31 at the Wayback Machine,Chandler 1987, Morris 2010,Turan 2010

- Chandler, Tertius; Fox, Gerald (1974). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-785109-9.

- "Address Based Population Registration System Results of 2010" (doc). Turkish Statistical Institute. 28 January 2011. Retrieved 24 December 2011.

- Morris 2010, p. 113

- Chandler 1987, pp. 463–505

- "The Results of Address Based Population Registration System, 2018". Turkish Statistical Institute. 1 February 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- "2007 statistics". tuik. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.

- "1980 Statistics". tuik. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- "Istanbul Asian and European population details" (in Turkish). 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

İstanbul'da 8 milyon 156 bin 696 kişi Avrupa, 4 milyon 416 bin 867 vatandaş da Asya yakasında bulunuyor (In Istanbul there are 8,156,696 people in Europe, 4,416,867 citizens in Asia)

- "Frequently Asked Questions". World Urbanization Prospects, the 2011 Revision. The United Nations. 5 April 2012. Archived from the original on 7 September 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- "File 11a: The 30 Largest Urban Agglomerations Ranked by Population Size at Each Point in Time, 1950–2035" (xls). World Urbanization Prospects, the 2018 Revision. The United Nations. 5 April 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- OECD Territorial Reviews: Istanbul, Turkey. March 2008. ISBN 978-92-64-04383-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Turan 2010, p. 224

- "Population and Demographic Structure". Istanbul 2010: European Capital of Culture. Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "History of Local Governance in Istanbul". Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- Kamp, Kristina (17 February 2010). "Starting Up in Turkey: Expats Getting Organized". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "Social Structure Survey 2006". KONDA Research. 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2012. (Note: Accessing KONDA reports directly from KONDA's own website requires registration.)

- Airport, Turkish Airlines planes are parked at the new Istanbul (24 July 2023). "Russian migration to Turkey spikes by 218% in aftermath of Ukraine war - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East". www.al-monitor.com.

- Barkey, Henri J. (2000). Turkey's Kurdish Question. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 9780585177731.

- U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. "Turkey: International Religious Freedom Report 2007". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Moceri, Toni (November 2008). "Sarigazi, Istanbul: Monuments of the Everyday". Space and Culture. 11 (4): 455–458. doi:10.1177/1206331208314785. ISSN 1206-3312. S2CID 143818762.

- "History of the Ecumenical Patriarch". The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Archived from the original on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- "The Patriarchal Church of Saint George". The Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- Çelik, Zeynep (1993). The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-520-08239-7.

- Herzig, Edmund; Kurkchiyan, Marina, eds. (2005). The Armenians: Past and Present in the Making of National Identity. Abingdon, Oxon, Oxford: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 133. ISBN 0203004930.

- Edhem, Eldem. "Istanbul." In: Ágoston, Gábor and Bruce Alan Masters. Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase Publishing, 21 May 2010. ISBN 1438110251, 9781438110257. Start: p. 286 and CITED: 290: "At the turn of the 20th century[...]only half of whom were Muslims."

- Baruh, Lorans Tanatar; Sara Yontan Musnik. "Francophone press in the Ottoman Empire". French National Library. Retrieved 2019-07-13.

- Kendall, p. 331.

- Balta, Evangelia; Ayșe Kavak (2018-02-28). "Publisher of the newspaper Konstantinoupolis for half a century. Following the trail of Dimitris Nikolaidis in the Ottoman archives". In Sagaster, Börte; Theoharis Stavrides; Birgitt Hoffmann (eds.). Press and Mass Communication in the Middle East: Festschrift for Martin Strohmeier. University of Bamberg Press. pp. 33-. ISBN 9783863095277. - Volume 12 of Bamberger Orientstudien - Old ISBN 3863095278 // Cited: p. 40

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 25 (PDF p. 27)

- Die Bevölkerungsgruppen in Istanbul (türkisch) Archived February 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "Fragmented in space: the oral history narrative: of an Arab Christian from Antioch, Turkey" (PDF).

- Aydınlık (2022-07-27). "İstanbul'daki sığınmacı sayısı açıklandı!". www.aydinlik.com.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-08-12.

- Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey Archived 2011-05-20 at the Wayback Machine Today's Zaman

- Strauss, Johann. "Twenty Years in the Ottoman capital: the memoirs of Dr. Hristo Tanev Stambolski of Kazanlik (1843-1932) from an Ottoman point of view." In: Herzog, Christoph and Richard Wittmann (editors). Istanbul - Kushta - Constantinople: Narratives of Identity in the Ottoman Capital, 1830-1930. Routledge, 10 October 2018. ISBN 1351805223, 9781351805223. p. 267.

- Strauss, "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire," p. 36.

- Kaloudis, George (2018-02-20). Modern Greece and the Diaspora Greeks in the United States. Lexington Books. p. 7. ISBN 9781498562287. - Old ISBN 1498562280

- Karpat, Kemal H. (1978). "Ottoman Population Records and the Census of 1881/82-1893" (PDF). Int. J. Middle East Stud. 9 (1): 237–274. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000088. S2CID 162337621.

- Celine, Pierre-Magnani (September 2009). Small Geography of the Istanbul Greeks. p. 29.

- Venizelos, Eleftherios (1919). Greece before the Peace congress of 1919: a memorandum dealing with the rights of Greece (PDF). New York: Oxford University Press American Branch. p. 19.

- McCarthy, Justin (2002). Population History of the Middle East and the Balkans. Isis Press. pp. 128–135. ISBN 9789754282276.

- Athanasopulos 2001, p. 82

- "The Greek Minority and its foundations in Istanbul, Gokceada (Imvros) and Bozcaada (Tenedos)". Hellenic Republic Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 21 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Thumann, M: Die Zeit, 22 Nov 2007, pp. 46–47, "Ein Volk, ein Staat, ein Krieg"

- Rôzen 2002, pp. 55–58, 49

- Rôzen 2002, pp. 49–50

- Brink-Danan 2011, p. 176

- ʻAner 2005, p. 367

- Staff, Toi (8 September 2018). "Ahead of Rosh Hashanah, figures show 14.7 million Jews around the globe". Times of Israel.

- Masters & Ágoston 2009, pp. 520–21

- Wedel 2000, p. 182

- Bahar Baser; Mari Toivanen; Begum Zorlu; Yasin Duman (6 November 2018). Methodological Approaches in Kurdish Studies: Theoretical and Practical Insights from the Field. Lexington Books. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4985-7522-5.

- Amikam Nachmani (2003). Turkey: Facing a New Millenniium : Coping With Intertwined Conflicts. Manchester University Press. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-7190-6370-1. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Milliyet Konda Araştırma (2006). "Biz Kimiz: Toplumsal Yapı Araştırması" (PDF). Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Agirdir, Bekir (2008). "Kürtler ve Kürt Sorunu" (PDF). KONDA. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Bekir Agirdir. "Kürtlerin nüfusu 11 milyonda İstanbul"da 2 milyon Kürt yaşıyor". Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Christiane Bird (18 December 2007). A Thousand Sighs, A Thousand Revolts: Journeys in Kurdistan. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 308–. ISBN 978-0-307-43050-2. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- Schmitt 2005, passim

- Cole, Jeffrey (2011). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. p. 366. ISBN 978-1-59884-302-6. Retrieved 17 May 2022.

- Elma Gabela (5 June 2011). "Turkey's Bosniak communities uphold their heritage, traditions". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- "Going cold Turkey: African migrants in Istanbul see hopes turn sour". IRIN. 2015-03-20. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Tuna, Banu. "Sakın çin çang çong demeyin" (Archive). Hürriyet. 11 November 2011. Retrieved on 11 August 2015.

- "学校紹介". Istanbul Japanese School. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

イスタンブールには、約110社の日本企業が進出し、約2000名の日本人が住み、そのうち約100 名の義務教育年齢の子どもたちが住んでいます。

- "中近東の補習授業校一覧(平成25年4月15日現在)" (Archive). Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). Retrieved on May 10, 2014.

- "Românii din Turcia, îngrijoraţi: "Noi plecăm de aici. Am mai trăit vremuri de dictatură"". adevarul.ro.

- "Artiști români de succes în Republica Turcia | TRT Romanian". www.trt.net.tr.

- "Pentru ce facem moschee la Bucuresti: In cautarea romanilor ortodocsi din Turcia".

- "A fost prelungit acordul de folosință a bisericii românilor din Istanbul, ctitorie brâncovenească - Basilica.ro". 4 November 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- "Preşedintele României a vizitat biserica românească din Istanbul - Basilica.ro". 23 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- Fatma Tanıs (26 September 2022). "Russian men flee the country. Many are showing up in Istanbul". NPR. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

External links

- "The Rum (Greek) community of Istanbul". TRT World. 2018-01-22.

.jpg.webp)