Denbigh, Cobbitty

Denbigh is a heritage-listed former vineyard, Clydesdale horse stude, Ayrshire cattle stud and dairy farm and now Hereford stud located at 421 The Northern Road in the southern-western Sydney suburb of Cobbitty in the Camden Council local government area of New South Wales, Australia. It was built during 1818 by Charles Hook in c. 1818 and by Thomas and Samual Hassall, and Daniel Roberts in c. 1828. The property is privately owned. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 22 December 2006.[1]

| Denbigh | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | 421 The Northern Road, Cobbitty, Camden Council, New South Wales, Australia |

| Coordinates | 33°59′40″S 150°42′37″E |

| Built | 1818 |

| Official name | Denbigh |

| Type | state heritage (landscape) |

| Designated | 22 December 2006 |

| Reference no. | 1691 |

| Type | Farm |

| Category | Farming and Grazing |

| Builders |

|

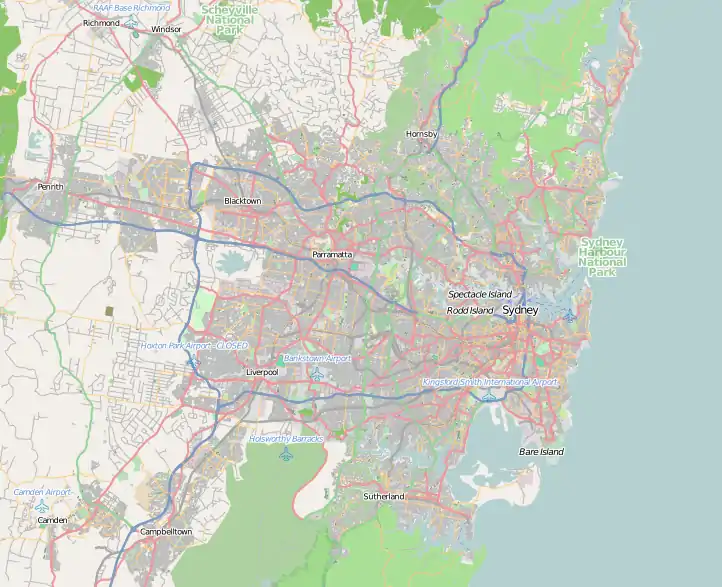

Location of Denbigh in Sydney | |

History

The original owner of Denbigh was Charles Hook, who had been imprisoned by the rebel government for supporting Governor Bligh's attempt to control the military in New South Wales. Hook had suffered greatly over the previous events and was in his fifties when he received his grant in 1812 by Governor Macquarie. The grant consisted of 445 hectares (1,100 acres) in the Parish of Cook, located at Cobbitty between the Cowpasture Road and Bringelly Road (later Northern Road). During 1818, Hook and his wife stayed at nearby Macquarie Grove while their own house was being built. The construction of Denbigh house was completed c. 1822 and Hook began clearing the surrounding land for agricultural use. He died in 1826.[1]

In 1826 the property was growing wheat (24 hectares (60 acres)) and maize (9 hectares (23 acres)). It was described as including "a large dwelling house and other convenient out-houses on the farm". Aborigines held "tribal rites" in the adjacent paddocks after the house was constructed. A dense grove of olives was planted west of the house pre-1826. A small vineyard was established on a hill to the north of the house pre-1826. A number of mud huts clustered around the main building, surrounded by a 2–2-metre (7–8 ft) paling fence (all now vanished).[2][1]

The property was then purchased by parson Thomas Hassall who began extending the homestead in 1827. It took four and a half years to complete major renovations on the house and service buildings. After its completion, Hassall was joined by his wife and children.[3][1] Hassall came to Australia from Otaheite (Tahiti) in 1797 and later married Anne Marsden, daughter of Bishop Samuel Marsden.[4][1]

Denbigh homestead resembled a scattered village surrounded mostly by an enclosed landscape with a half circle of hills, five acres of gardens consisting of an abundance of fruit trees, a vineyard and an orange grove with magnificent views from the hills. Together with a wide extent of country, churches were clearly seen at nearby Camden, Narellan and Cobbitty.[5][1]

Convict labour was used on the property and Hassall had in his employment, "twelve to twenty men" managed by a Scottish overseer. In the Hassall days, Denbigh existed as a small scattered village with its own school master, blacksmith, carpenter, brickmaker and many others.[6][1] Hassall also employed local Aboriginal people to help burn off excess timber on the property to clear land for extensive farming activities. During this period, a corroboree was held on the Denbigh estate in which 400 Aboriginals took part.[2][1] Hassall recalled witnessing numerous corroborrees on the property overlooking Cobbitty Creek.[7][1] In 1828, Hassall financed the construction of Heber Chapel in Cobbitty which he built on his nearby grant in which Cobbitty Road ran through. Fifteen years earlier, Hassall had established the first Sunday School for children in Australia, which he ran from his parents' house in Parramatta.[1]

After 1826 when Hassall was the owner, the property was used to grow wheat and wool, and included vineyards and orchards. From the early 19th century a bakehouse, meat-room and cellar, laundry and store room were located on one side of the courtyard. Denbigh under Hassall included a resident school master, a carpenter, brick maker, blacksmith, shoemaker, dairyman, three gardeners, butler and coachman (including coach house). Denbigh under Hassall had between a dozen and 20 convicts assigned to the household. Denbigh later in the Hassall period was set in a garden of five acres, including an abundance of fruit trees.[2][1]

By 1845, tenant farmers were purchasing their own land. With fewer servants being employed at the property, combined with the lack of available labour, Denbigh homestead contracted back to a nucleus of farm buildings much like it was during 1820.[1]

In 1866 Charles McIntosh, a Scottish farmer, leased land at Denbigh which he purchased the following year, the year Thomas Hassall died. The property was used to breed Clydesdale horses.[1] From 1910, Denbigh became a dairy farm and an Ayrshire cattle stud.[1]

Today, Denbigh is still owned by the McIntosh family and is used as a Hereford stud.[1][8]

Description

Farm

.jpg.webp)

The original land grant remains intact with substantial 19th century built fabric remaining. The (original Hook) entry gates to Denbigh are simple by design and the unsurfaced estate road leads through paddocks and groves of eucalypts.[1] Many of the cultural and historic plantings remain on the property such as remnant mature eucalypts. Older plantings include an avenue of forest red gums (Eucalyptus tereticornis) to the north-east of the homestead garden along an earlier farm access path, reputedly planted by Charles Hassall.[1]

Two other cottages exist on the farm: Bangor closer to The Northern Road and the main entrance driveway, to the east of the Denbigh homestead complex, and Cluny, on Cluny Hill south-west of the homestead group. Cluny cottage was originally located to the north-east of the homestead complex on "Plantation Hill" - then known as Roberts' Cottage, before it was moved to its current location.[1] A former quarry remains on the farm. An older driveway access from the Hassall era led south to Cobbitty Road and towards the village of Cobbitty.[1]

Garden

.jpg.webp)

A curving driveway leads through a second set of gates and an unkempt wilderness area of predominantly olive trees, shrubs and vines where it terminates in front of the house which has a highly maintained and formal garden (a common element of a 19th-century landscape design). This grove of olives was planted pre-1826 on the western side of the homestead for shade and shelter. Here the Hassall ladies walked in the afternoons. As well as the old carob tree (in 2009 a large dead stump but with a vigorous young shoot maturing)[8] there is a kurrajong (Brachychiton populneum), Bunya Bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii) and peppercorn trees (Schinus molle var. areira) in this area.[1] Denbigh retains its cottage garden, simple in design with plants fashionable in the 19th century complementing its colonial atmosphere.[1]

Older plantings include roses, carob (Ceratonia siliqua), century plant (Agave americana) and its variegated form "Variegata", a Bunya Bunya pine (Araucaria bidwillii). Between the homestead and outbuildings stands a candelabra /cactus tree (Cereus peruvianus) a curious botanical specimen with large white trumpet flowers originated from South America and the only known example of its kind in the Camden Municipality. Many other species of trees remain on the property and are typical of 19th century plantings in the district. These include African and fruiting olives (Olea europaea var. africana and O. europaea), sweet gum (Liquidambar styraciflua), Cocos Island/Queen palm (Syragus romanzoffianum), ash (Fraxinus excelsior).[1]

A tennis court north-west of the homestead is almost hidden from view by lush climbers such as cat's claw creeper (Doxantha unguis-cati).[1]

A Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis) north-east of the house was planted in 1948 to commemorate a marriage in the owners' family.[1] The garden in summer is filled with the scent of old-fashioned roses - gallicas, bourbons, banksias, damasks, musks and rugosas and scented pelargoniums. Bushes of Rosa chinensis "Old Blush", a China rose are scattered through the garden. These were the first species of rose to be grown in the colony.[1] The Mediterranean cypress (Cupressus sempervirens) on the eastern side of the garden was reputedly planted by Hassall and the Hassall girls once played croquet in this part of the garden.[1]

In the homestead's rear (kitchen) courtyard beside the old well and pump are bushes of Hibiscus mutabilis "Plena" (double, white-pink) and H.moschatus (single, white-pink). Sandstone gutters drain this paved courtyard towards the outbuildings to its south. A gate at the far northern end leads through the western wing of outbuildings to the shrubbery / wilderness to the west.[9][1]

Homestead Complex

.jpg.webp)

The homestead is sited in contrast with the surrounding open agricultural land and is complemented by the half circle of hills which define Denbigh's landscape character. In terms of elevation and character, the buildings and trees have been sited in a manner influenced by John Claudius Loudon, the Scottish writer on landscape taste.[1]

The house looks across the fields to the north to a line of hills where a small vineyard was established ('Plantation Hill'). It is here that, after a trip to Wollongong where he had been given seeds, Hassall planted some cabbage tree palms (Livistona australis) and others which he described as those of a "silver tree". The palms are gone today and were unusual in the district.[6] NB: In 2001 Plantation Hill is bushy now - the cabbage palms are gone, although a "silver tree" does remain, suckering from its base). To the north-west and above an area of African olives was a clearing planted with a "native vineyard" of native vines, a botanical collection, which is of interest to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney.[10][1]

The house consists of timber framing, filled with brick or rubble nogging and covered in weatherboard. The hipped roof extends over the house and the brick paved verandah is supported on square timber posts with chamfered edges. The chimneys have a simple brick cornice with a distinct colonial character. Renovations can be evidenced by joinery typical of the 1830s. The whole structure is now rendered.[1]

Outbuildings

.jpg.webp)

In the Hassall days, Denbigh existed as a small scattered village with its own school master, blacksmith, carpenter, brickmaker and many others.[1] Twelve to twenty assigned servants maintained the 5-acre (2 ha) garden of orchards, vegetables, the vineyard and orange grove on the side of the hill.[6][1] The present farm buildings are located conveniently near the house which include slab built sheds and an old barn with thick rubblestone walls. The barn still bears the engraved initials of Thomas Hassall cut into the timber architrave.[1]

A huge forest red gum (Eucalyptus tereticornis) is the centre piece to the farm buildings, coach house and stables block. Further east and uphill are a range of outbuildings, slab huts and sheds.[1]

Condition

As at 14 January 2002, the Denbigh property is of archaeological potential to reveal evidence of both early European farming practices and Aboriginal occupation. A number of mud huts were clustered around the main homestead, surrounded by a 2–2-metre (7–8 ft) paling fence (all now vanished).[1]

Denbigh is an intact farm estate within the Cumberland Plain and Camden region. The original 1812 land grant and the relationship of the homestead to important views also remains intact.[1][11]

Modifications and dates

- Charles Hook's original grant was 490 hectares (1,200 acres). In 1826 he had 24 hectares (60 acres) of wheat and 9.3 hectares (23 acres) of maize here, a "large dwelling house and other convenient out-houses on the farm". A small vineyard was established on a hill to the north of the house pre-1826. A number of mud huts were clustered around the main homestead, surrounded by a 2–2-metre (7–8 ft) paling fence (all now vanished).[1]

- 1827-31: The original one storey house and outbuildings had major renovations undertaken by Rev. Hassall, adding a bedroom storey in 1827. Hassall added a southern entry drive connecting the property to Cobbitty Road (and the Heber Chapel and church).[1]

- Other service and farm buildings were built during renovations soon after the purchase of the property by Thomas Hassall, the number of which were reduced in the 1840s.[1]

- A former quarry remains on the farm. The former Roberts Cottage site and associated fences is to the homestead's north-east. This cottage was (date unknown) relocated to Cluny hill south-west of the homestead group and remains in use as a residence. Another cottage, Bangor lies to the east of the homestead group close to the estate road to The Northern Road.[1]

- 1866+ use of farm to breed Clydesdale horses.[1]

- 1910+ use as a dairy farm and Ayrshire cattle stud.[1]

- 2009: use as a Hereford cattle stud.[1]

Heritage listing

.jpg.webp)

As at 29 July 2003, Denbigh is of State significance as an intact example of a continuously functioning early farm complex (1817-1820s) on its original 1812 land grant. It contains a rare and remarkable group of homestead, early farm buildings and associated plantings with characteristics of the Loudon model of homestead siting within an intact rural landscape setting fundamental to its interpretation. The large collection of early farm buildings is perhaps the most extensive and intact within the Cumberland/Camden region.[1]

It has historic associations with pioneering Anglican minister Thomas Hassall and its relationship with the early Heber Chapel and the township of Cobbitty. The estate is significant as an early contact point between Aboriginal and European culture and is of social significance for the descendants of the Hassall and Macintosh families. It retains its historic views across the valley to Cobbitty in the west.[1]

The place is of scientific significance for its potential to reveal, through archaeology, evidence of both early European farming practices and aboriginal occupation. The significance of Denbigh is considerably enhanced by the extent to which it has retained its form, character, fabric and rural setting (Heritage Office).[1]

The Denbigh estate is of exceptional cultural significance for its historical, aesthetic, social and technical values.[1]

The homestead and attendant farm buildings are an exceptionally rare and intact group of structures dating from the very early 19th century. They demonstrate the aspirations of, and continuous occupation by only 3 families as well as the continuous evolution of their farming and grazing practices over this period. The extant structures, intact pastoral landscape, associated family and public records archives, all combine to make this a very rare and important place in the history and evolution of NSW. This is strengthened by the survival of significant physical and historic links with the surrounding early roads and settlements as well as significant buildings and structures built by the Hassall family, the second family to own the estate. It is one of several important colonial estates in the local area including Maryland, Wivenhoe, Brownlow Hill and Raby.[1] The establishment of the Denbigh farm by Charles Hook (1809-1826), its subsequent ownership and development by the famous "galloping parson" Thomas Hassall (1826-1886), and then by the MacIntosh family to the present time, connects the place with very important figures in the development of this area of NSW.[1]

The physical evidence of Aboriginal occupation of the estate, both prior to and after European arrival backed up by documented evidence of this including ceremonial use, strengthens the integrity and rarity of the continuous physical record of the place. Important named historical Aboriginal figures such as Cannbaygal, a visiting chief from the mountains, are associated with the Denbigh farm, and possibly also Cogy (Cogrewoy) a leader of the "Cowpastures" Tribe who also acted as guide through the district to Macquarie and Barrallier.[1] The fact that the landscape remains as undeveloped agricultural /pastoral land, retains the sense, both physically and visually of this connection with all of these periods and occupations.[1] The Denbigh farm estate retains a curtilage and setting of exceptional historic and aesthetic significance. Unlike most of its early colonial contemporaries in the Cumberland Plain, it retains this curtilage and setting in a largely uncompromised state, and thus its integrity, from the time of early European occupation.[1] The landscape and setting of the homestead and outbuildings and the views to and from these, provide a very rare and intact early colonial landscape of great beauty and integrity and of exceptional cultural significance to the state of NSW.[1] The Denbigh estate contains areas of varying significance in relation to their role in the curtilage of the place.[12][1]

Denbigh was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 22 December 2006 having satisfied the following criteria.[1]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Denbigh is of historical significance on a state level as an intact example of continuously functioning early farm complex on its original 1812 land grant.[1][13]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

Denbigh has significance for its association with pioneering Anglican minister Thomas Hassall and its relationship with the early Heber Chapel and township of Cobbitty.[1][13]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Denbigh has aesthetic significance as a remarkable group of early farm buildings with associated plantings including the avenue of forest red gums (Eucalyptus tereticornis) established by Thomas Hassall. The large collection of early farm buildings retains its scattered village atmosphere and is an extensively intact farm estate on the Cumberland Plain. Adjoining landscapes continue the sense of historic rural character. Denbigh's landscape is identified in the Camden Significant Tree and Vegetated Landscape Study and the Colonial Landscapes of the Cumberland Plain and Camden study for the National Trust of Australia.[1][13]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Denbigh has social significance as an early contact point between Aboriginal people and European's. It also has social significance for the descendants of the Hassall and Macintosh families and has demonstrated its popularity as a venue for select tourist groups.[1][13]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Denbigh has scientific significance in regards to Aboriginal occupation and can demonstrate the theory and practice of colonial landscape design and farming practices.[1][13]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Denbigh is a rare example of an intact colonial farm complex and homestead. The property has continuously functioned as a farm since 1817 and is located on its original grant area. Denbigh is rare as a farming estate with characteristics of the Loudon model of homestead siting.[1][13]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Denbigh is representative of early farming practices and an example of typical 19th century landscape design.[1][13]

References

- "Denbigh". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H01691. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence. - Godden Mackay Logan, 2007, 27

- Baker, Helen (1982). Denbigh - Historic Homesteads, Australian Council of National Trusts.

- Robinsons, 1962

- Hassall, Rev, James S. in "Old Australia, Records and Reminiscences from 1784", Brisbane, 1902

- Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens, 2001

- Godden Mackay Logan, 2012, 20

- Read, Stuart; pers.comm.

- Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens, 2001 with additions from Stuart Read, visit of 29/9/2001

- Ian McIntosh to Stuart Read, pers.comm., 29/9/2001

- Heritage Office draft.

- Design 5, 2004, 37

- Heritage Office draft

Bibliography

- Design 5 Architects (2008). Denbigh 421 The Northern Road, Cobbitty, NSW 2570: conservation management plan and curtilage study.

- Design 5 Architects; Britton, Geoffrey (2004). Denbigh Estate, Cobbitty - Detailed Curtilage Study.

- Friends of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney (2001). Denbigh garden - Cobbitty (notes, prepared for a visit by).

- Godden Mackay Logan (2012). East Leppington Rezoning Assessment - Heritage Management Strategy, draft report.

- Godden Mackay Logan (2007). GCC Oran Park Precinct Heritage Assessment (Denbigh, in Appendix I).

- Landarc Landscape Architects (1993). Camden Significant Trees and Vegetated Landscape Study.

- Morris, Colleen; Britton, Geoffrey (2000). Colonial Landscapes of the Cumberland Plain and Camden, NSW.

- Morris, C.; Britton, G.; NSW National Trust; Heritage Council of NSW) (2000). Colonial Landscapes of the Cumberland Plain and Camden, NSW.

- Philp, Anne (2015). Caroline's diary: a woman's world in colonial Australia.

- Robinsons; Tucker & Co. P/L - NSW agents for Chateau Tanunda - the brandy of distinction (1962 brochure) (1962). Map no. 121 - Sydney & Environs - Historic Buildings and Landmarks.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Denbigh, entry number 01691 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Denbigh, entry number 01691 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.