Dendraster excentricus

Dendraster excentricus, also known as the eccentric sand dollar, sea-cake, biscuit-urchin, western sand dollar, or Pacific sand dollar, is a species of sand dollar in the family Dendrasteridae. It is a flattened, burrowing sea urchin found in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean from Alaska to Baja California.

| Dendraster excentricus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ganges Harbour, British Columbia, Canada | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Echinodermata |

| Class: | Echinoidea |

| Order: | Clypeasteroida |

| Family: | Dendrasteridae |

| Genus: | Dendraster |

| Species: | D. excentricus |

| Binomial name | |

| Dendraster excentricus Eschscholtz, 1831 | |

| Synonyms [1] | |

| |

General information

Dendraster excentricus is an irregular echinoid that is flattened and burrows into the sand, unlike the regular echinoids, or sea urchins. It can be found living in the Pacific Ocean from Alaska to Baja California. The range for Dendraster excentricus is larger and includes the range of the other two extant species of Dendraster: D. vizcainoensis and D. terminalis. The flower pattern in this species is off-center, giving it the species name excentricus. Its test (skeleton) is compared to that of a sea urchin below.

Description

They are colored gray, brown, black or shades of purple. Their size is variable, averaging 76 mm with the world's largest found measuring 120 mm wide.[2] They have a dome shaped carapace varying in height to about 10 mm with a circular body or test. Their body is covered with fine, spiny tube-like feet with cilia, and like other echinoderms they have five-fold radial symmetry. The mouth, anus, and food grooves are on the lower (oral) surface and the aboral surface has a petalidium, or petal shaped structure, with tube feet. Dead individuals have a gray/white test, or skeleton, which is often found washed up on beaches. It has a water-vascular system from the internal cavity or coelom that connect with tube feet. The tube feet are arranged in five paired rows and are found on the ambulacra—the five radial areas on the undersurface of the animal, and are used for locomotion, feeding, and respiration. Spines are generally club shaped in adults, and less so in juveniles. The five ambulacral rows alternate with five interambulacral areas, where calcareous plates extend into the test. At the center on the aboral side is the madreporite—a perforated platelike structure, and on the interambulacra are the four tiny genital pores. Radiating out from the genital pores are the five flower petals, which represents the ambulacral radii. The mouth is in the center on the bottom side, with the anus toward the edge.

Dendraster Excentricus Sizes (World's Largest on Right)

Dendraster Excentricus Sizes (World's Largest on Right) Test of a dead D. excentricus

Test of a dead D. excentricus Oral side of D. excentricus

Oral side of D. excentricus Diagram of aboral side

Diagram of aboral side Diagram of oral side

Diagram of oral side D. excentricus aggregation at low tide

D. excentricus aggregation at low tide Comparison of test of Dendraster and sea urchin

Comparison of test of Dendraster and sea urchin

Habitat

They are either found subtidally in bays or open coastal areas or in the low intertidal zone on sandy on the Northeast Pacific coast. They can live at a depth of 40 to 90 meters, but usually is found in more shallow areas. Sand dollars are usually crowded together over an area half buried in the sand. As many as 625 sand dollars can live in one square yard (0.85 sq m). It is the only sand dollar found in Oregon and Washington. It has been found on Burfoot Beach in the South Puget sound.

Behavior and feeding

Like its cousins, dendraster is a suspension feeder which feeds on crustacean larvae, small copepods, diatoms, plankton, and detritus. Adult sand dollars move mainly by waving their spines, while juveniles use their tube feet. The tube feet along the petalidium are larger and are used for respiration while tube feet elsewhere on the body are smaller and are used for feeding and locomotion. They frequently move around if they are lying flat. When feeding they usually lay at an angle with their anterior end buried and catch small prey and algae with its pedicellariae, tube feet, and spines and pass them to the mouth. Their mouth includes a small Aristotle's lantern structure found in most Echinoids. In high currents adults grow heavier skeletons while juveniles swallow heavy sand grains to keep from being swept away. They will bury themselves when they are being preyed on.

Hydrofoil design

This particular species of sand dollar is known for its curious behavior:

When exposed to a steady flow of water, they gather in groups, forming aligned rows in the sand, while digging their front edge in and raising their back edge into the flow of water, lined up so it passes from right to left across their bodies. Because the shape of a sand dollar is a hydrofoil, this draws particles of food closer in to their mouths during feeding, a benefit enhanced by the alignment of many individuals together into a communal feeding group.

Reproduction

Sexes are separate, with no noticeable differences in external features of the two sexes. Reproduction is sexual and D. excentricus reaches sexual maturity between 1 and 4 years of age, spawning in late spring and early summer. Fertilization is external, the female Dendraster discharges the eggs through her gonopores and they are fertilized by the male, who protrudes his genital papilla from his body wall. This is one reason they are believed to live in large groups and tend to release gametes at the same time into the water column. Eggs are pale orange, and are covered by a thick jelly coat which keeps adults from eating the eggs.

Development

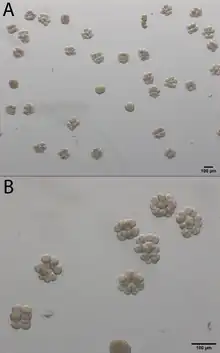

The first larval stage is called a prism. After this stage the embryo will develop two arms transforming itself into an echinopluteus larva. This is followed by the development of arms, until it reaches 8 arms all together. After this the larva develops an echinus or juvenile rudiment, which will become the juvenile. The nektonic larvae are pelagic and travel away from the parent group with the current. The developed larvae will receive a chemical cue from adults to settle down into a bed of sand dollars and begin to undergo metamorphosis to their adult sand dollar form. As adults they are benthos and stay on the sandy bottom.

Lifespan and predation

Predators include the seastar Pisaster brevispinus and the starry flounder Platichthys stellatus as well as crabs and sea gulls. They are sometimes settled on by a small barnacle, Paraconcavus pacificus.[3] Large storms or high temperatures and desiccation can cause mass mortality if low tide coincides with a hot midday and the animals are exposed to air for just 2 to 3 hours or washed up and buried in the sand. Old age is thought to be the main cause of death of Dendraster excentricus. They may live up to 13 years and can be aged by counting growth rings on the plates of the test or by counting the pores in a petal of the petalidium.

Conservation

The habitat they live in on the sandy seafloor is sometimes damaged by bottom trawling, causing harm to many organisms. Ocean acidification and sea surface warming also harm populations of sand dollars.

References

- Dave Cowles (2006). "Echinarachnius excentricus (Eschscholtz, 1831)". Walla Walla University. Archived from the original on June 2, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

-

- Sand dollar from Olympia beach may break a record HeraldNet, August 21, 2013

- Morris, Robert H.; Abbott, Donald P.; Haderlie, Eugene C. (1980). Intertidal invertebrates of California (1st ed.). Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-80471045-7. OCLC 7043400.

- Dendraster excentricus Intertidal Marine Invertebrates of the South Puget Sound

- Dendraster excentricus Walla Walla

- Biogeography of the Western Sand dollar San Francisco State University

- Sand dollar, Monterey Bay Aquarium

- The persistence of a sand dollar, OnEarth.org

- Strathrnann M. 1987. Reproduction and Development of Marine Invertebrates of the Northern Pacific Coast. University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington. 670 pp.

- Marin Jarrin, Jose R. "Embriogenesis and Larval Stages of Dendraster excentricus". 2007. University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon.

- Smith, Andrew. 1984. Echinoid Palaeobiology. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Further reading

- Rich Mooi. "Sand Dollars of the Genus Dendraster (Echinoidea:Clypeasteroida): Phylogenetic Systematics, Heterochrony, and Distribution of Extant Species". Bulletin of Marine Science, 61(2): 343–375, 1997.

- Friedrich von Hellwald - The standard natural history, Volume 1, The Standard Natural History, Elliott Coues, Editors John Sterling Kingsley, Elliott Coues. Publisher S.E. Cassino and company, 1884, Pages 171–172.